Sha Na Na Tova

Happy New Year from a doo-wop singer who opened for Jimi at Woodstock, then became a biblical scholar

Alan Cooper doesn’t look like someone who played at Woodstock. On a recent afternoon, one of those thick and sticky Manhattan days that make you yearn for winter, the 66-year-old JTS professor was sitting at a table in an Italian restaurant, in a yellow Oxford shirt that hung big on his thin frame, with a plain olive baseball cap pulled down over his bald head. He was talking about the younger sister he recently lost to pancreatic cancer: Her funeral was on a Friday afternoon, and because you can’t sit shiva on Shabbat, everything was thrown into flux. Suddenly we were discussing Judaism’s laws and their intent, which brought us to the Golden Calf. “It’s after that incident that the Jews get all their rigorous rules,” he said, between bites of pasta. “The lesson: Jews are bad at improvising, and they shouldn’t try it because if they do, well, you end up with a Golden Calf.”

Cooper, the former singer for Sha Na Na, the band that warmed up Woodstock’s Bethel, New York, stage for 30 minutes before Jimi Hendrix came out to deliver the most electric rendition of the national anthem ever performed, has a master’s degree in philosophy and a doctorate in religious studies, both from Yale. His dissertation was on the linguistic structure of biblical poetry. According to his official bio, he is the Elaine Ravich Professor of Jewish Studies and provost of the Jewish Theological Seminary.

“I always loved learning, especially the Hebrew language,” Cooper said. “But I became more interested in the phenomenon of religion my junior year in college after taking a course on ancient texts. That class opened my eyes to a new way of studying the bible.”

Still not convinced? Here’s a passage from Cooper’s 2002 essay, “The Message of Lamentations”:

I have been intimating that there is no longer any intrinsic reason to read the book of Lamentations in the light of the biblical canon, or to fit it into the frame of some biblical theology. Despite the undeniable heuristic power of those intertexts, I find it equally plausible and illuminating to place Lamentations in a different discursive context—the popular lament literature of the ancient Near East, and the widespread “personal religion” that it manifests.

Jimi Hendrix had Purple Haze. Alan Cooper has that.

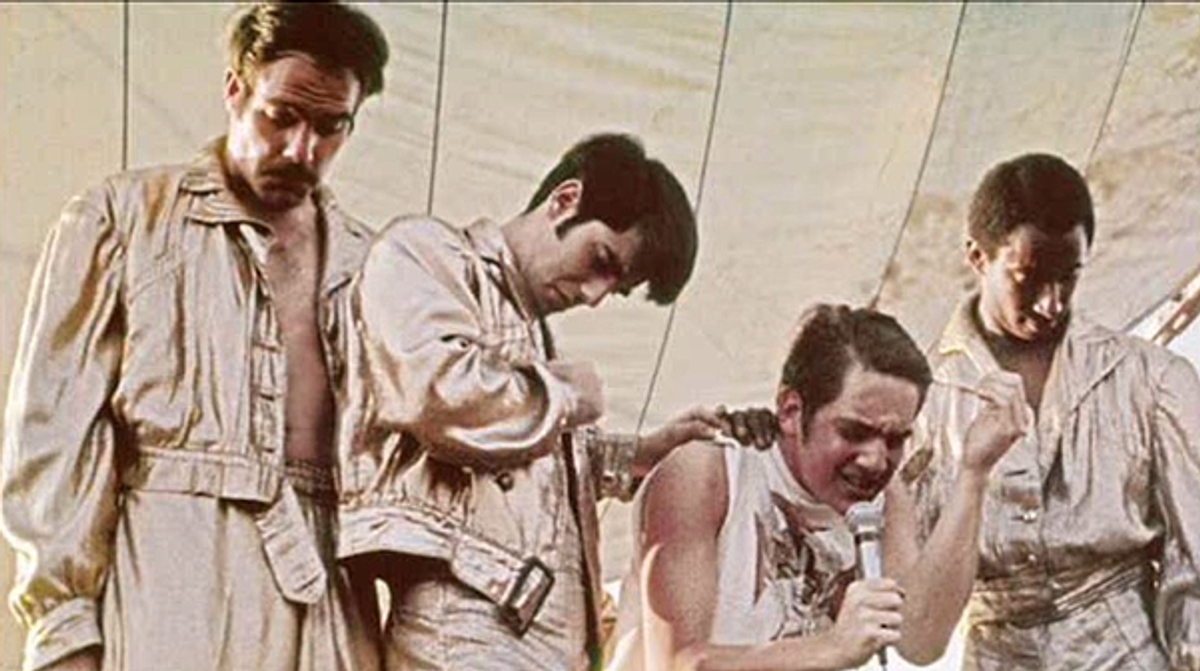

Sha Na Na was Woodstock’s penultimate performance and the 11th act seen in the documentary. There they are, all 12 members, bouncing and shaking and gyrating, limbs flying everywhere, for 52 glorious and immortalizing seconds, with thousands of long-haired and bearded and shirtless young men and women signing along. And there’s Cooper, on the lead vocals, belting out the lyrics to “At the Hop,” the catchy doo-wop tune released by the band Danny & the Juniors in 1957, wearing a yellow vest with no shirt underneath, dark sunglasses, and a leather cabbie hat. Snapping his fingers and tapping his feet, he looks about 50 pounds heavier than he is today. He has a full head of hair. Sideburns, too.

“The whole experience was just phenomenal,” Cooper said.

That Sha Na Na ever garnered an invitation to Woodstock in the first place is semi-miraculous. The group was an evolution of the Kingsmen, the all-male Columbia university singing troupe formed in 1948 and known for signing slow a capella jazz and doo-wop. Johnny Mathis’ “Misty” and Nat King Cole’s “When Sunny Gets Blue” were two of their favorites. On Christmas, they’d perform in front of a Yule log.

Cooper arrived on Columbia’s campus in the fall of 1967 and joined the Kingsmen soon after. A few months later the group decided to put on a concert at the Lion’s Den, the student union. They had written a number of originals but didn’t have enough to fill out an entire show. “So we decided to learn a bunch of hit ’50s and ’60s songs because they were easy, fun, and we could pick up a bunch of them fast,” Cooper said. The Rays’ “Silhouettes,” the Monotones’ “Book of Love,” the Five Satins’ “In the Still of the Night.” “The audience went berserk.”

Cooper estimated that there were 100 students at that show, but said that performance was the trigger for the band’s improbable rise. Afterward, a brother of one of the band’s members convinced the group that they could have a future in music if they continued singing popular covers—but they had to look the part, too. So they learned some ’50s-style choreography and raided the closets of their older siblings in search of sequined shirts and pointed shoes. Cooper, who sang and played keyboard, began greasing his hair. They put on another show, in a bigger campus auditorium, and passed out fliers promoting it as a night off from all the unrest permeating the country. Even more people showed up. There was another show in the spring of ’69—held outside, they called it Grease Under the Stars. It rained a little bit, but the audience was even larger. “That’s when we thought that we maybe we can do this over the summer and make some money,” Cooper said.

Cooper and Joe Witkin, a pianist from the group, then took Witkin’s car down through the East Village and back up the West Side in search of a club willing to give them a shot. Most turned them down. The Scene, owned by a music executive named Steve Paul and tucked away in the basement of a building on 46th Street just off Eighth Avenue, granted the Kingsmen—who by then had changed their name to Sha Na Na—an audition. They performed “Wipe Out” and their usual closer, “Rock ’n’ Roll Is Here to Stay,” and wore gold costumes that they had rented from a Bye Bye Birdie touring company. The club manager, Teddy Slatus, “was blown away,” according to Cooper. He booked Sha Na Na for 100 nights that summer and told them he’d pay $50 a show, double on weekends.

It was there that Michael Lang, one of Woodstock’s organizers, discovered Sha Na Na. “Steve Paul’s The Scene,” the moniker used by most when referring to the club, was known as a Theater District hot spot, a favorite hangout among Broadway’s elite looking to wind down after their shows. It also attracted big-name rockers like Janis Joplin and Hendrix, who, according to Sha Na Na drummer John “Jocko” Marcellino, was responsible for bringing Lang to one of the bands’ shows.

“They were great,” Lang recalled. “They were very different, sort of like a look back at our rock ’n’ roll roots. I thought they’d fit in well with what we were putting together, that most of the people who would be at Woodstock had grown up listening to this music in the ’50s.”

Lang went backstage and introduced himself to the band. He told them that he was putting together a music festival that would be taking place in mid-August in upstate New York. He offered them $700. The 12 members had to split it.

“Of course, we said yes,” Cooper said. “To be part of the Woodstock Festival—I mean, come on!”

Here’s what Alan Cooper, Ph.D. and Bible professor, remembered about being backstage at Woodstock:

“After awhile, they ran out of drinking water. But there was always plenty of champagne, beer, and dope.” He also enjoyed the camaraderie with the other bands, especially the English blues-rock band Ten Years After. “They were so friendly and congenial and shared all the stuff they had,” he said.

He remembered the rain Friday night, and the beautiful amphitheater where the festival took place, and being able to hear the music from miles away. And, thanks to the rain, waiting until Monday morning to play.

“The show was supposed to end on Sunday, and so by that time, half the people had already left,” Cooper said. “But there were still, like, 20,000 people there, by far our biggest audience ever.”

Sha Na Na played a 30-minute stretch before ceding the stage to Hendrix. “I wanted so badly to watch him,” Cooper added. “After the performance, I found a spot on the side of the stage where I could see the whole thing.” That fall Cooper and the rest of the band returned to Columbia’s campus, where they resumed living as students—but also performing on the weekends in clubs like the Fillmore.

Three years later, Cooper graduated with a degree in religion and decided it was time for his rock ’n’ roll career to end. He had always been drawn to Judaism, specifically its language and texts. As a kid, he’d fill out Hebrew grammar forms while riding the bus as child from his Long Island home to West Hempstead’s Hebrew Academy of Nassau County. Just before he turned 13, Cooper’s family moved to Livingston, New Jersey. He became involved in the local Conservative synagogue. He joined the choir and learned how to lead the prayer service.

“My father couldn’t understand it,” Cooper said. “He couldn’t imagine why anyone wouldn’t want to become an entertainer—or how anyone could make a career as a biblical scholar.”

I pointed out to Cooper that typically in these stories the fathers are the ones pushing their sons away from the music.

“The truth is he had phenomenal music talent himself, but he grew up dirt poor during the Depression,” Cooper said. “He loved music more than anything else but he was never able to realize that passion because he had to focus on earning a living.”

After earning his master’s and doctorate at Yale, Cooper found a job at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, where he taught religion for 10 years. But it was in the summer of 1977 that he found his true calling. He and his wife had moved to Israel for the season, and there he met one of his idols, Rabbi Moshe Greenberg, a renowned Bible scholar at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University who Cooper said changed his life.

“He was someone who had this special and intelligent sense of what it meant to be a scholar and a Jew,” Cooper said, “and he pulled me aside one day and says, ‘Someone with your talent should be putting it into serving the Jewish community.’ ”

A few years later, Cooper heard about an open position at Hebrew Union College, the Cincinnati-based Reform seminary, and applied for the job.

On a Friday night in June, Cooper and 10 other original Sha Na Na members were invited back to Columbia to perform at the school’s 2016 reunion. Forty years had passed since Cooper last stepped onto a stage. They spent Thursday night eating dinner in a private room in a Theater District Italian restaurant and bits of Friday rehearsing. Cooper was happy to be back behind a mic, but also because this would be the first time his wife and their son and daughter would see him perform live.

After Cooper left Sha Na Na, the band replaced many of its original members with professional singers and entertainers. The group’s music appeared in Grease, and they put out a number of hit albums and even had a syndicated TV show. The group is still active, but on this night the current members agreed to share the spotlight with those who paved the way.

Shortly after 8 p.m., the original members were introduced. First, there was bassist Bruce Clarke, then guitarist Henry Gross. Finally, Cooper’s name was called. He was wearing sunglasses and the same outfit he wore to Woodstock—a cabbie hat and gold vest, only this time he had a shirt on underneath. He strolled onto the stage slowly, hands tucked into the pockets of his black pants. The rest of the band followed behind. He was handed the mic. The keyboard let out the first few and fast notes of “At the Hop.” Cooper turned, smiled, began bouncing his feet and snapping his fingers, then raised the microphone to his lips.

“They say you can’t go back again, but we did,” Cooper said a few weeks later when I ask him about that night. “It was just a magical night.”

Yaron Weitzman is regular contributor to Bleacher Report and senior writer for SLAM magazine. His work has also appeared in The New Yorker, New York, and The Ringer. His Twitter feed is @YaronWeitzman.