Death in Venice Beach

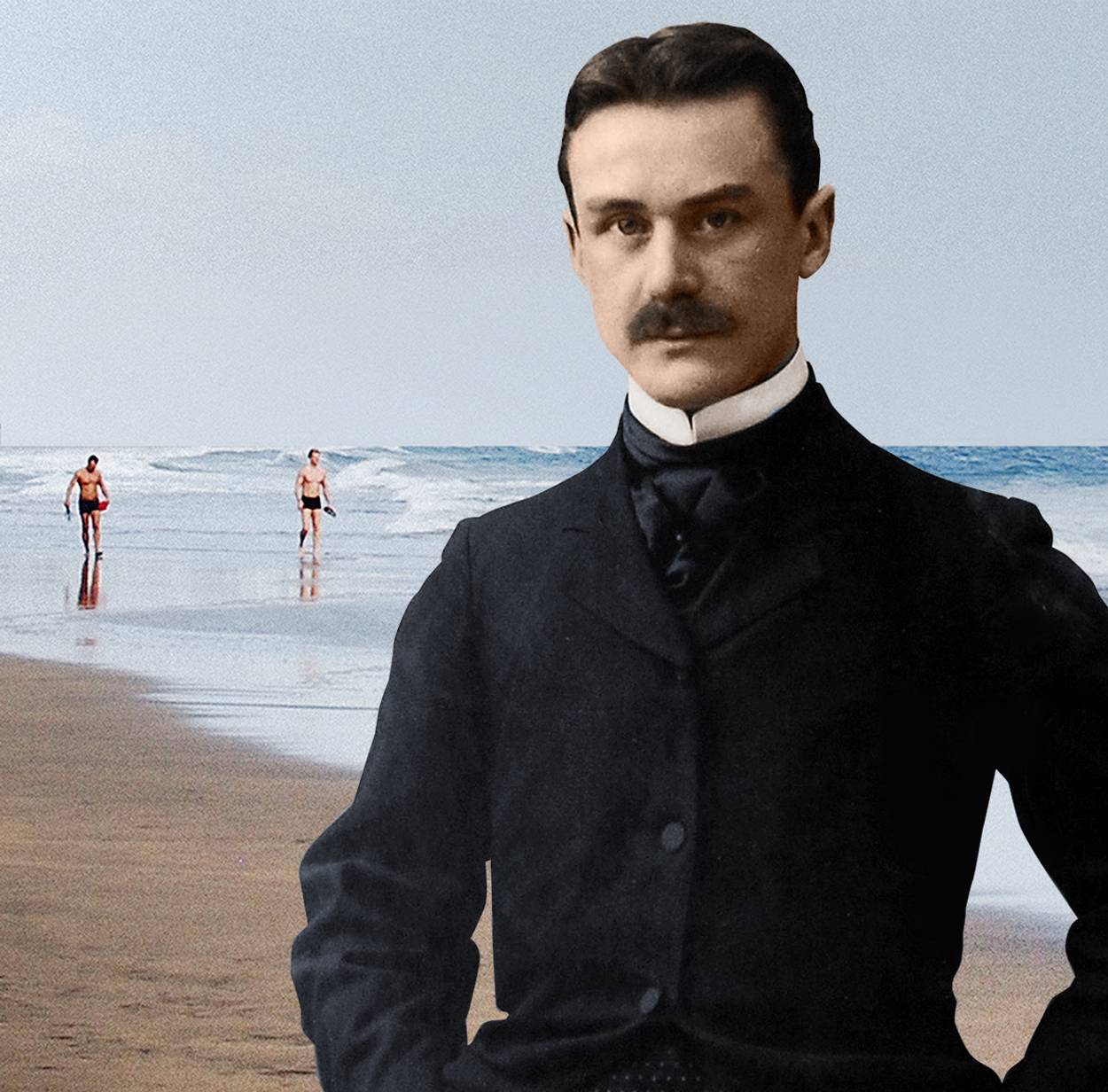

On Thomas Mann’s 145th birthday, his protagonist Aschenbach’s Romantic wanderings in the virus-laden swamps of lechery and sickness at the edge of civilization, ring—not true, exactly, but closer

The washed-up critic in me continues to think about Gene Wilder, of all people—his character in Blazing Saddles: the alcoholic gunslinger The Waco Kid (the wake-and-bake kid). I’d say it’s time for a comeback! So I responded to my editor’s ironic invitation to a Mets game this spring with the famous last line of The Sun Also Rises, “isn’t it pretty to think so?” And that quickly, this Waco kid was back at it. So I intuitively kept going with my pitch—“the subject I’m finding most compelling in my class-Zoom (in no way can it be called a class-room) is the book we’ve been studying: Death in Venice, by Thomas Mann. But what if he goes for it? So now I’m obligated to compose an essay on one of modernism’s most unsympathetic protagonists, Gustav von Aschenbach—and make this perverted old white guy likable.

I was suddenly mounting my defense of Aschenbach—of his literary snobbery; his obsession with Greek mythology; his suffering to express his genius using his God-given German words; his daily drudgery opening an endless stack of fan mail; his angst and burnout from having to be such an arrogant Übermensch all the time; his high standards and uncompromising work ethic; his narcissism; his analytical precision peering through his own masquerade; his elitism; his sworn duty to the highest of arts; his devotion to the knight errantry of a sublime aesthetic … But ultimately, his urge—while on vacation in Venice—his monstrous compulsion to examine an effeminate Polish boy named Tadzio (pronounced -a-Jew) as if through a shotgun’s scope.

Ashenbach, who I would call an unsympathetic hero (as opposed to a sympathetic antihero), is a barely veiled stand-in for Mann himself, who was Germany’s anti-Fuehrer, the writer they looked to in hope of regaining their composure after a period of pretty dismal literature (Mein Kampf). Mann deserves much credit for being highly critical of the Weimar culture, far before Hitler even rose to power. And he did receive a Nobel Peace Prize for his attempt to talk some sense into the German volk. He even made monthly anti-Nazi broadcasts during the war (via the BBC) berating Hitler and his grotesque cronies. And after he fled to the United States (he lived in Pacific Palisades, in Los Angeles, just a stone’s throw from my favorite hangouts in Venice Beach), he remained just as outspoken, stressing out many a German expat about the necessities of collective guilt.

Seen in a fascist light, Mann certainly does not come across as a villain. Aschenbach, however, has qualities that in today’s world are (as I like to warn my college students) troubling.

Passages in the first chapter lead us to wonder what’s eating Gustav von Aschenbach?—what’s frustrating this dignified man of letters? Indeed, it wouldn’t appear to be too complicated: He is suffering from burnout. And needs time to reboot. And so he gives orders to “prepare his country house.” Country house? Of course. Where else would an artist of such stature go to get some peace and quiet? But Aschenbach admits that the purifying mountain air will not satisfy his “juvenile thirst for the distant.”

Aschenbach then encounters an enigmatic stranger who is “obviously not a Bavarian.” He wears a broad-brimmed hat, carries a rucksack strapped on his shoulder, and holds a stick with an iron tip in his right hand (like Hermes). But what does Aschenbach hope to find in this underworld, i.e., Venice? “The unfamiliar and unrelated” we are told—the diverse culture of a place less obsessed with uniformity, homogeneity, and racial purity than his native soil—a place where “gaily ragged people converse in an alien-sounding language.”

This upstanding literary citizen is hard up for a seat at a café, where he may hunker down and do some serious people watching. As I ask my students, have you ever located that perfect corner seat at a bar, where you can sip a cocktail, view a living collage of energized strangers, and maybe jot down a poem on a napkin with a borrowed pen? I’m happy if I can just get one kid to crack a smile. The point is that most of them are so locked to their screens that they wouldn’t, and probably never will, discover the urban sport of getting lost.

Perhaps Mann’s Aschenbach is also an expression of Mann’s envy for the Parisian flâneur’s noble form of procrastination—time spent sauntering, loafing, aimlessly strolling … boulevardiering! In “The Painter of Modern Life” Baudelaire writes: “For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate spectator, it is an immense joy to set up house in the heart of the multitude, amid the ebb and flow of movement, in the midst of the fugitive and the infinite. To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the centre of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world …” He goes on: “The spectator is a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito. The lover of life makes the whole world his family … the lover of universal life enters into the crowd as though it were an immense reservoir of electrical energy.”

Aschenbach is compelled to go on a journey to the southern dreamscape of Venice, in search of the exotic. And when he carefully boards a gondola, he finally begins to let go. Which is when the reader begins to empathize with his palpable anxieties—his suspicion, for example, that the gondolier is ripping him off by taking him on a detour, and his repulsion for an old man he spots in a wig with slipping dentures and clownish cosmetics trying to appear younger and more vibrant than he really is. Aschenbach is like the cliché of that hopelessly square grown-up who finally stops resisting what the kids are all doing and awkwardly takes that quintessential first puff … and coughs his lungs out … and starts to giggle wildly. The metaphorical drug, however, seems a bit harder and diabolical (like morphine or opium or heroin). Aschenbach observes: “has one noticed that the coffin-black-varnished, black-upholstered chair in such a barge is the softest, most luxurious, most deeply relaxing seat in the whole world?”

Finally Aschenbach steps off the solid continent onto his boat and feels his fundamental stature, his stabilizers, give way. He begins to bridge the gap, philosophically, between the two rivalrous sons of Zeus—the Apollonian disposition (the god of the sun, of rational thinking and order, who appeals to logic, prudence and purity) on one side, and on the other, that of the Dionysian (the god of wine and dance, of irrationality and chaos, and appeals to emotions and instincts). He is, in this way, invoking the dueling tensions highlighted in Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy, which is furthermore an expression of a fascination with Richard Wagner’s Norse pagan revival—essentially myths of the pure blooded Aryan. (It is perhaps worth noting that Mann was apparently obsessed with Wagner and had an extensive library of recordings of his most famous opera Tristan und Isolde.)

It is at this point that Aschenbach (who is said to have been endowed with the physical traits of another major composer, Viennese Jew Gustav Mahler) gets tangled up in the braiding currents running beneath and through the city-on-stilts and with the virus contaminating the sultry “scirocco” (or mist), which settles into the ancient port of Venice like a phantom.

Here, long before he knows his mental or physical health is even at risk, (long before he would have thought to check the nearest pharmacy for a tube of Purell!), Aschenbach begins to relax: allowing himself to be corrupted by the pleasures of the warm climate and loose aura: “the traveler closed his eyes to enjoy that kind of unusual and sweet lassitude. The trip will be short, he thought; oh would it last forever!” It’s as if he’s just shot up a vein and tips his head back in the cushions of his internal organs and begins to nod out.

And when he instructs his bellhop to set his trunk down in his tranquil hotel room, he knows he is officially prepped for poetry. He walks to the lofty window, looks out at the beach, and feels the afternoon’s emptiness, as the sea continues to “send long, low waves with rhythmic beat upon the sand.” He is back at tabula rasa, alone, silent, speechless. His thoughts are “sluggish, yet more wayward, and never without a melancholy tinge.” Aschenbach reasons: “solitude gives birth to the original in us, to beauty unfamiliar and perilous” but also to “the perverse, the illicit, the absurd.” And in the midst of such thoughts, “he salutes the sea with his eyes.”

What if the story were to end here? In a way, our protagonist has gotten what he came for, a joyride on a very seductive, very homoerotic/homophobic gondola (the gondolier is not treated so well). At this 19th-century Romantic high point, we sense closure—as Aschenbach appears to plug back into the natural periodic order of life, and the perceived hierarchy of nature’s authority.

But a day later, our arrogant writer finds himself reclining under a cabana reflecting on his latest vulgar pleasures: “in a balmy night … with the garish lights and melodious sounds of the serenade receding.” And he recalls his ordinary phantasmagoric perch above the ethnic fray where ravens occupy the branches of fir trees and thunderstorms make “the lights in the house go extinct.” He shoots back to his current liminality within a bong hit of decadence to the “softly-cooling breath of Oceanus,” where “the days take their course in blissful idleness, without effort, without struggle.”

By now we feel for this sad, sad man, who has had to flee the giant security guards of his German identity at the gate of his tortured heterosexual soul. I personally feel for Aschenbach’s melancholic longing for, well … something new? His exile is not dissimilar from my own. I too have fled to a beach town, where fishing boats are anchored. I too am contemplating my own demise as my aspirations dissipate in the salty air rolling off the breakers, as my dreams turn to ruins without ever coming to fruition. I can relate to this old man’s ambivalence, and to his need for an intoxicant. I respond in my daily correspondence to a friend’s question “how long are you gonna stay down there sheltering in place?” with the thrilling single word: indefinitely.

But our fictional famous author Gustav von Aschenbach was born with a silver fountain pen in hand, and tremendous expectations of achievement. He was one of these child prodigies who peaks early and therefore misses out on “the idleness and carelessness of youth.” A man in one scene describes Aschenbach by forming a fist. “He always lived like this,” the man says. He then lets his fingers open and allows his heavy arm to drop, “never like that.”

Aschenbach is clearly wound too tight; he came of age into a perpetual midlife crisis. We should all be so uninspired, the wise rabbi might caution.

Mann deserves credit for his painfully excavated creation. Street cred is due for sure to the auteur, for his writerly potency and indelible document of arrogance and tactical perversion. The book definitely passes the degenerate test! But he also deserves credit for his commendable tolerance of the Jews, which in the year 1911 would have signaled remarkable open-mindedness just about anywhere in the world. Mann’s wife and mother of his five somewhat damaged children was Katia Mann, who came from a very wealthy reputable German Jewish family. Mann had the guts to go first—to marry a Jew, and then to wade even further into taboo waters. He certainly does deserve credit for putting it all on the line—for presenting the world with an authentic proto-Nabokovian, pre-Humbertian perv; Aschenbach is the archetype of a shameful pedophile, voyeur and stalker all rolled into one—the uber-creep!

We zero in on the muse the way I’d imagine Michelangelo would have salivated on a giant chunk of perfect marble. And then we watch Mann skillfully carve out his long-haired boy of about 14 “with clustering honey-colored ringlets, the brow and nose descending in one line, the winning mouth, the expression of pure and godlike serenity.” Mann is often less the macho sculptor and more the flamboyant hairstylist: “No scissors,” he writes, “had been put to the lovely hair that curled about his brows, above his ears, longer still in the neck.” And he is even a bit fetishistic, when he dresses his doll in a sailor suit: “with quilted sleeves that narrowed round the delicate wrists of his long and slender though still childish hands,” with its “breast-knot, lacings, and embroideries,” lending him a “spoilt, exquisite air.”

But rather than make the boy harmless, he injects him with (projects onto him) an ornery and slightly angry personality, creating, for lack of a better word, a conceited little prick, a nasty little prince, a Jr. Fuehrer—the coverboy for August’s edition of Teen Fascist.

I’m reminded of an 8-year-old boy I once had the pleasure of meeting at a family gathering. He was the very spoiled son of some wealthy Goldman Sachs bankers on my wife’s WASPy side. He apparently had the idea in that little extravagant mind of his, to demoralize me, to punish me for … I guess having a dark, Jewish complexion, let’s imagine. And for no other motive that I could discern, he announced to his mommy with outrageous authority that I had hit him—which was inconceivable since I was standing a good 3 feet away, and was now being introduced for the first time.

Was it a case of mistaken ideality? Or was I just a victim of a child’s innate thirst for evil. Who knows, but I’ll never forget. I’ll never feel safe from that child’s dream of cruel tyranny, any more than he is likely to ever escape his true nature.

It is this sort of tangled-up suspenseful exchange that Mann tries to deliver, not just a flaccid staring contest on a crowded beach. And my hat is off to him, of course, as it is to Baudelaire, Flaubert, and especially the infamous poète maudit Comte de Lautréamont for his pre-surrealist character Maldoror, whose violently psychopathological poems were unambiguously intended to turn readers inside out, as if he were breaking into their homes and abducting them from their crusty old parents.

Mann was not a French radical bohemian hiding like a depraved pickpocket in the underground; he was a respectable public figure. Death in Venice, autobiographical as it is, was a high-stakes game of confession and self-incrimination. Throughout the book, we feel we are seeing through Mann’s eyes, living in Mann’s brain, “enveloped in that white sheet” in the barber’s chair. The book is perhaps most famous for its wonderful passage where Aschenbach’s metaphorical death mask (as I see it) is carefully applied. The metamorphosis: “He watched it in the mirror and saw his eyebrows grow more even and arching, the eyes gain in size and brilliance, by dint of a little application below the lids. A delicate carmine glowed on his cheeks where the skin had been so brown and leathery. The dry, anemic lips grew full, they turned the color of ripe strawberries, the lines round eyes and mouth were treated with a facial cream and gave place to youthful bloom.”

Aschenbach continues to up his game. He moves from voyeur to stalker. His eyes cling to his perfect little dictator. He shifts in his seat to examine the boy’s profile and is knocked out again by the head of Eros. After regaining his composure and his dignity, from his obvious gawking, and putting back on his patronizing air he notices the lovely youth’s loitering pace and hastens his own step, hustling up behind him on the boardwalk that ran behind the bathing cabins … which is where he almost breaks the look-but-don’t-touch rule. He “all but puts out his hand to lay it on shoulder or head.” His heart now throbbing, he begins to pant, and gasp—my God the poor writer is about to go into cardiac arrest.

This brings me to the real threat to the ominous novella. It is not the threat of a desirous gaze upon an unsuspecting (or suspecting) youth; nor is it the threat of involuntary impulses in times of disorienting dreamy sensuousness (leaning in for a kiss); nor is it the threat of coming out of the closet to face public scorn. It is coming out of the closet to the first inhalation of the mist wafting up off the stinky contaminated canals carrying a lethal virus.

As I thought about this fact, chronicling the historic event we are presently living through due to COVID-19, Death in Venice takes on a new significance. The real villain is not a washed-out white man over 30 or an arrogant boy under 18. The story’s symbolic problem, at least read today, is no longer the morality of the monster but the cruelty of nature. The star of the opera is not a boy with the features of Ronan Farrow, or a silver fox from a civilized continent. It is an odor, and an unsubstantiated rumor.

“He spoke to a shopkeeper lounging at his door among dangling coral necklaces and trinkets of artificial amethyst, and asked him about the disagreeable odor. The man looked at him, heavy-eyed, and hastily pulled himself together. “Just a formal precaution, signore,” he said, with a gesture. “A police regulation we have to put up with. Aschenbach thanked him and passed on. And on the boat that bore him back to the Lido he smelt the germicide again.”

Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, Goodbye Letter, was published by Hunters Point Press.