Sonnets for the Trilingual Family Man

Eugene Ostashevsky’s latest collection is a love letter to his wife, his children, and the beauty of language

This article is the third installment of Tablet’s celebration of National Poetry Month. Take a look at the previous entries on Sean Singer’s “Today in the Taxi,” Victoria Redel’s “Paradise,” and Dan Alter’s “My Little Book of Exiles.”

To write fresh and compelling sonnets in the 21st century takes a great deal of craft. But what does it take to reinvent the sonnet form altogether? In Eugene Ostashevsky’s case, it takes gumption, playfulness, a mastery of many languages, a wide range of intellectual reference, and above all, a whole lot of wit. In his The Feeling Sonnets (NYRB, 2022) you will find every kind of humor: There’s parody and absurdism, slapstick, hyperintellectual snickering, cross-lingual puns, and dad jokes.

This collection is bursting with references to avant-garde movements, philosophy, literary theory, classics, the Bible, the Talmud, and, I’m sure, a whole lot more: There is something here to go over anyone’s head. Although Gertrude Stein is not directly invoked in Ostashevsky’s collection, her presence looms large—the usage of short, quickly morphing phrases and the bending of sonics and grammar are recurring devices that run through most of the poems in this book and are reminiscent of Stein’s style and sound.

The comparison with Stein doesn’t end there, however. Stein’s work was shaped, in large part, by her expat sensibility, and that is true for Ostashevsky as well. The poet was born in St. Petersburg, lived much of his adult life in the U.S., and now resides in Berlin with his family. What is particularly touching is not merely that he has moved across cultures and languages, but done so with his young daughters. It feels that their language exploration invigorates his own, as in: “Papa, says Eva holding a brownish apple, schmeiss this weg. I schmeiss it weg. / We live in Berlin” (“schmeiss weg” means “throw away” in German). Even more poignantly, he writes: “To be a child all over again is to be learning to speak all over again. The Russian word for language is the Turkish word for pity or shame. / If next time you exclaim ‘alas,’ you wish to do it in Turkish, you cry ‘yazık!’ / If you address a dead person and get no reply, you can say ‘ne yazık,’ which is the same as ‘too bad.’”

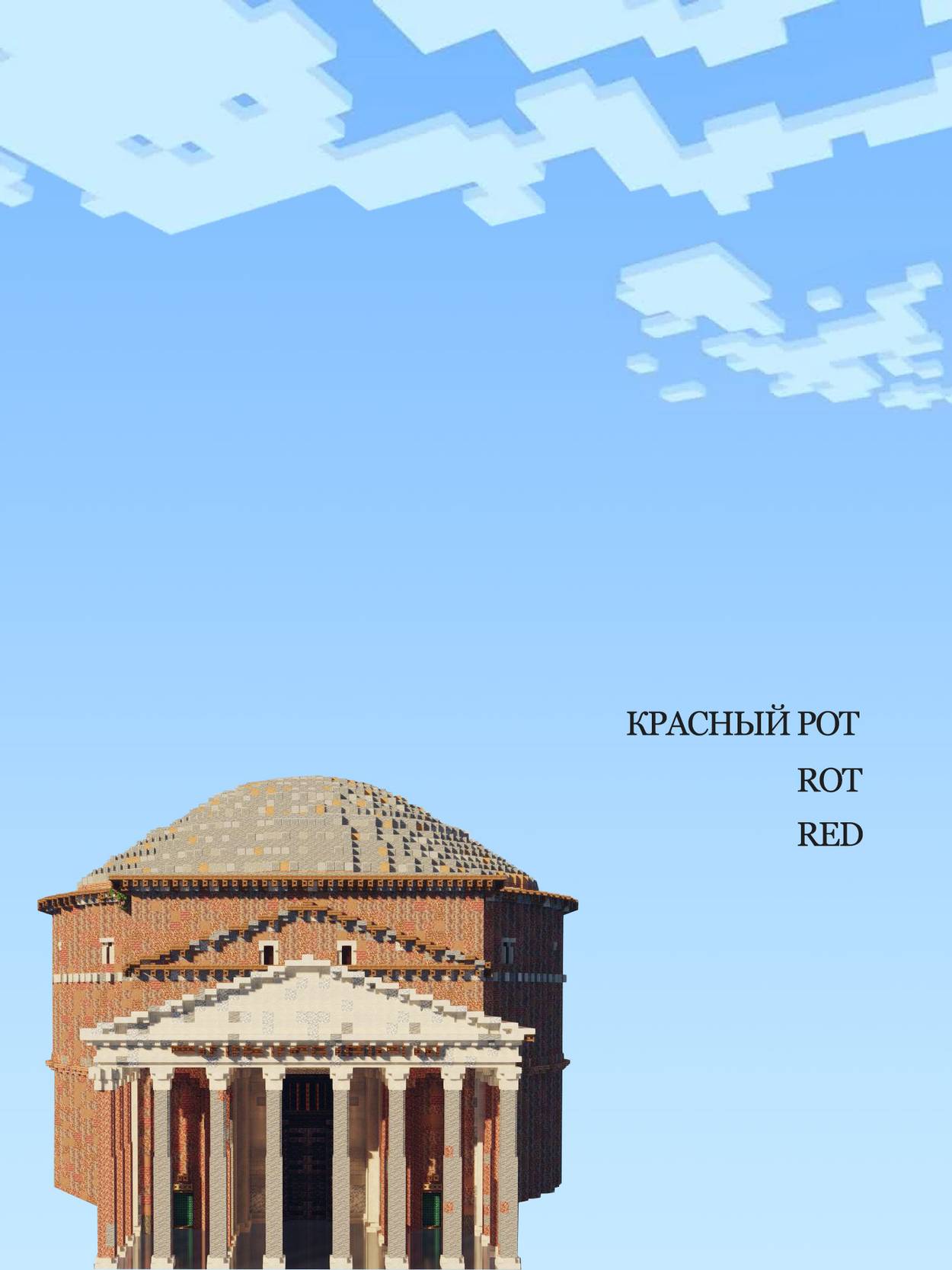

The first of the two poems we’re featuring today is the poet’s delightful interaction with his daughter Una, who responds to the grandeur of Rome with an urge to build it in Minecraft, and who, ultimately, schools the poet for his ignorance. It is very clear, that, for the poet, the splendor of Rome pales in comparison to the dialogues with his own child. You will note, though, that this sonnet, as most classic sonnets do, contains 14 lines, and there is a volta, or turn, in between the octave and the sestet—and, just in case, it is even directly named as such.

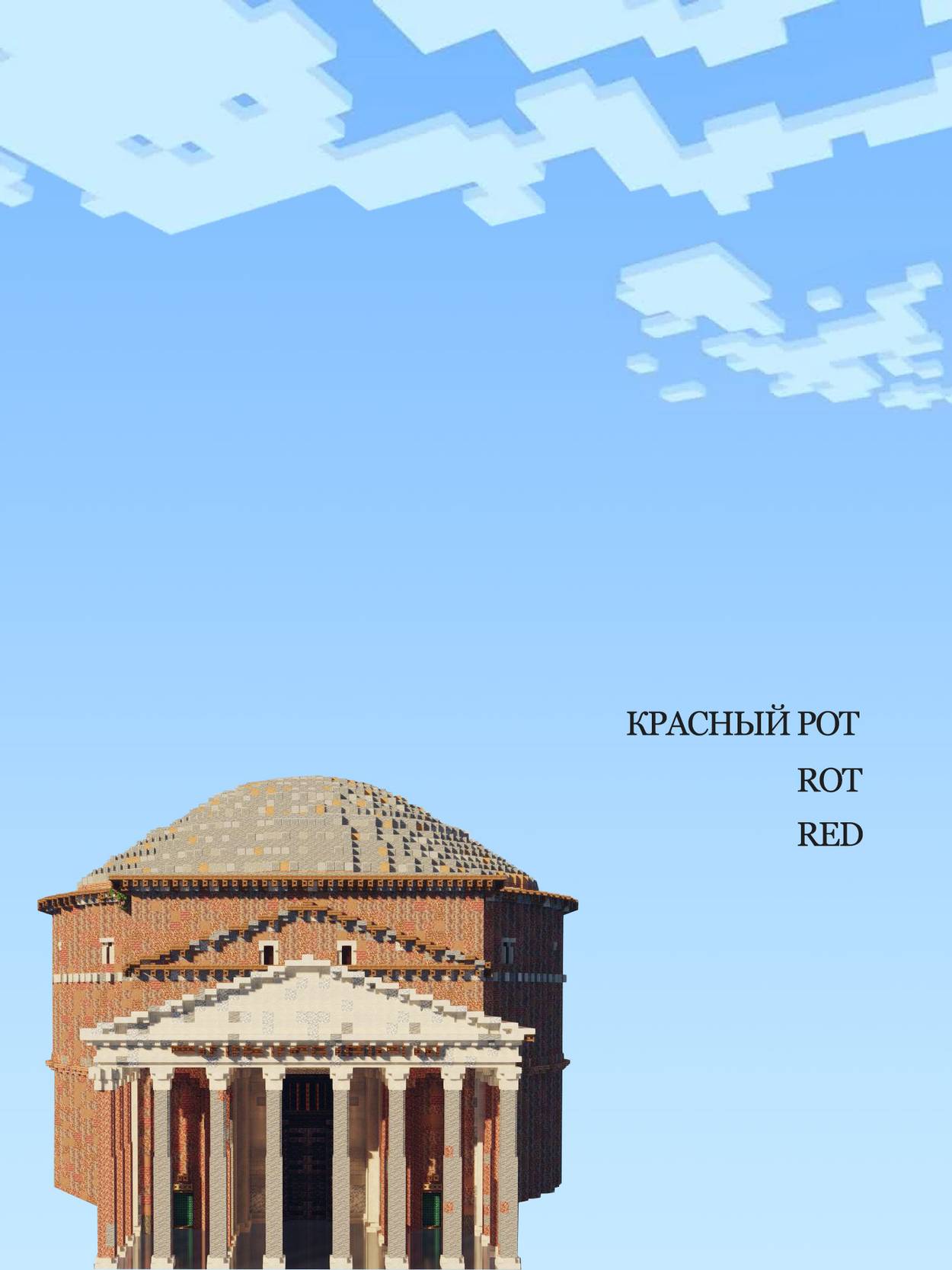

The second poem featured here is a more direct interaction with the capacities of the sonnet form. It is both a love poem and a parody of it, which is, perhaps, the best kind of a love poem, for what can be more romantic than: “Your body smells like a woman’s body, sometimes quite strongly”? The opening line here is a direct riff on Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116, but whereas the old Bard penned the line “Love’s not Time’s fool, though rosy lips and cheeks,” our bard Ostashevsky reimagines it, plugging in a Russian phrase, красный рот which means, literally, “a red mouth.” It is pronounced “krasniy rot,” and that is significant, because later in the poem, the word “rot” trots over into the territory of the English word “rot,” as in “decay,” and then into German “Rot,” which means “red.” This is a love poem, even perhaps an erotic poem, but the object of affection is not only a person, but language and literature, too. This sonnet ends on a Rastafarian note.

Many of us multilingual immigrants tend to compartmentalize ourselves when speaking one language or another: As the old saying goes, you can’t play a saxophone and also eat fish at the same time. Ostashevsky, however, seems to be able to, and I, for one, cannot begin to explain the sense of elation of watching him jam across boundaries and impossibilities. His verse may not compare to a summer’s day, but who needs a summer’s day in the dusk of this trilingual immigrant virtuosity?

51.

Una won’t clean her room but she keeps building cities in Minecraft.

When we visited Rome she said, “I would like to build it in Minecraft.”

Take that, Augustus! My Augusta found Rome in brick, but she will leave it in Minecraft.

Among the green parrots of the Palatine she publicized it for all the world.

There was only one Rome, now there’s more. That’s amore? No, it’s Minecraft.

The Forum is “ate ‘em” today—it’s double the ruin with Minecraft!

The pontifex climbing the Capitol Hill with the priestess of Vesta (they do not know what to say to each other) discovers a twin brother in Minecraft. O loop-de-loop, are we to rename you “She-Wolf”?

All the sonnets ever turned out by tourists now have daughter sonnets.

“Una, get off your computer!” “But I got on only now!”

“Una, get off your computer!” “Papa, get out of my room!”

“Speaking of your room, do you have any plans to clean it?” “But I already cleaned my desk today!”

“Where did you clean your desk? My eyes are going bad, I can’t see the clean part.” “Papa, get out of my room!”

“I just hope this is not what your room looks like in Minecraft, ok?”

“Why do you even talk about Minecraft? You have no clue about it whatsoever.”

7.

Time’s fool, you have a красный рот. You know what I’m saying.

Also the lipstick rubs off easily.

Your body smells like a woman’s body, sometimes quite strongly.

Your pupils are like the black pearls of Madagascar. Look at how they sit inside their oysters, that is at their desks.

A blazon is that what this is. A night watch.

Does it tell time. What does it tell time.

Stop, mighty time! For my body is falling.

I wake up in the middle of the night and my body is falling. The Babylon of my body is falling.

My body is multilingual. It sticks out its tongues but they say the same thing. Ah.

It signs signs. Sign, rot. Enter by gate and the inside is rot.

Unbowed towers and untoward bowers, rot. Riders on squares with never a river, rot. Images ending pilgrimages, rot.

Dead fountains smothered with foliage.

O time’s fool. I worship at all your altars. I worship at your красныйрот. Ist das mein Rot oder dein Rot. What are you saying.

My altars alter. My altars falter. My altars totter. My body, my body, my body, the Babylon of my body is falling.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).