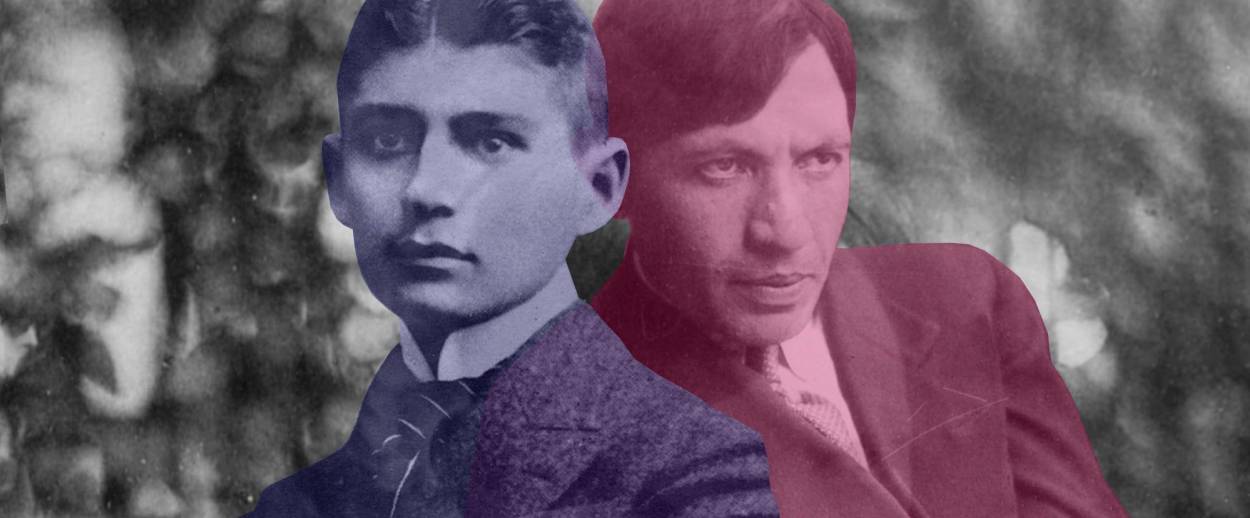

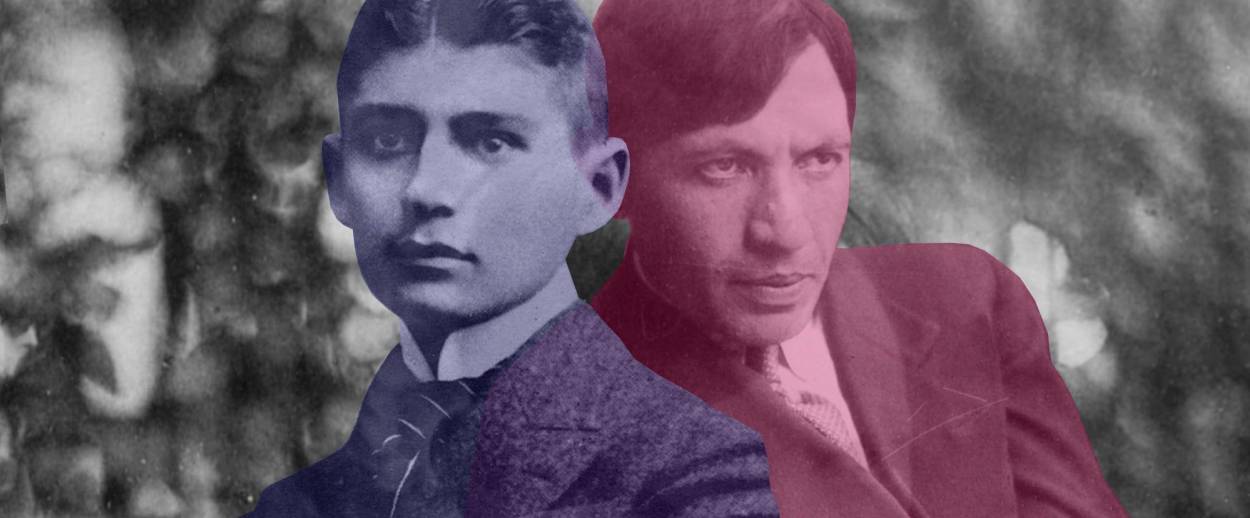

Soutine Is the Kafka of Painting

Twinned artistic prophecies of the destruction of the Jewish people in Europe, on Chaim Soutine’s 125th birthday

Franz Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony” was first written in 1914 at the start of the Great War. Two years earlier, in 1912, the impoverished 19-year-old Chaim Soutine had arrived in Paris with 50 rubles in his pocket and speaking no French. Soutine came from a small town in Russia and was from an Orthodox Jewish background. By contrast Kafka came from an assimilated Czech-Jewish family where the spoken language was German. His father was a prosperous store owner in Prague. And yet the two men, one in painting, the other in writing, prophesied the same thing in their work: the destruction of the Jewish people in Europe.

According to John Updike who wrote the forward to Franz Kafka: The Complete Stories:

Out of his experience of paternal tyranny and decadent bureaucracy he projected nightmares that proved prophetic. A youthful disciple, Gustav Janouch who composed the hagiographic Conversations with Kafka once raised with him the possibility that his work was “a mirror of tomorrow.” Kafka reportedly covered his eyes with his hands and rocked back and forth saying, “You are right, you are certainly right. Probably that’s why I can’t finish anything. I am afraid of the truth … One must be silent, if one can’t give any help … For that reason all my scribbling is to be destroyed.”

Janouch also says that Kafka, as they were passing the Old Synagogue in Prague (the very synagogue Hitler intended to preserve as a mocking memorial to a vanished people), announced that men “will try to grind the synagogue to dust by destroying the Jews themselves.”

In both Kafka and Soutine one encounters “projected nightmares that proved prophetic.” Ezra Mendelson, the noted historian, agreed with Updike: “Kafka’s novels and stories are propelled by the logic of nightmare.” That quality—“the logic of nightmare”—is what I saw in some Soutine paintings as well. (In others, the paintings were more like a reenactment of the nightmare’s feeling.)

In 1943, Soutine became a victim of the Nazis in France. As a result of a serious ulcer condition he needed immediate medical care, but because he’d be discovered as a Jew by the authorities at the hospital, he had to hide in a truck. To throw off the authorities the truck took a circuitous route arriving at the hospital 24 hours late. By that time Soutine was very ill. He died on the operating table.

So often in stories pertaining to Jews there is that fatal 24-hour time gap. If only the philosopher/writer Walter Benjamin had been 24 hours earlier or 24 hours later, there would have been no reason for him to take his own life at the Spanish town of Portbou. Kafka, on the other hand was perhaps fortunate to have died 10 years before the Holocaust. But his three sisters were all murdered by the Nazis.

Kafka and Soutine were born 10 years apart: the former in 1883, the later in 1893, 125 years ago today. Between 1893 and 1924 their lives overlapped, although there is no record of them ever meeting. Some of Kafka’s stories in German were already published in the early 1900s, but it is unlikely that Soutine read any of them or even knew of the author.

I first became conscious of a connection between Kafka and Soutine this past summer in Paris. On one of my first days there I went with a student to l’Orangerie to see again Monet’s water lily paintings. (This museum is where the eight huge pictures hang in two empty oval rooms designed specifically for them.) I was completely bowled over by their beauty. The paintings were followed by another exhibition, American Abstract Painting and the late Monet. I’d had to come all the way to Paris to see it. I was familiar with the idea that the main influence on abstract expressionist painting had been late Monet. My friend the art critic Clement Greenberg had written an essay about it in his seminal book, Art and Culture. Still, I was thrilled to see the show, which featured quotes from Greenberg on most wall cards, and even a few photos of him.

But there was more—a whole room of Chaim Soutine paintings! What were they doing here? I read the wall statement and learned that l’Orangerie, in addition to housing the eight lily pictures, is home to the Jean Walter-Paul Guillaume Collection, which includes several Soutines—it is, in fact, the largest collection of his work in Europe. The first picture to catch my eye was “Still Life With Pheasant.” After taking it in I turned to my student and blurted out, “Soutine is the Kafka of painting.” The picture specifically brought to mind, “In the Penal Colony,” with its instruments of torture and execution.

The hose-like contraption coming out of the pitcher’s spout elicited a memory of the torture machine in “In the Penal Colony,” which is used to murder individuals for undefined crimes. The pheasant’s feet look human, with even a suggestion of shoes, as if the body had been tortured by the spouted pitcher and left to die. Incongruously planted in the foreground is a thin red pepper.

Next, I turned to a canvas titled simply “The Table.” Equally disturbing are the two undefined objects which can be read as mutilated corpses. Were these trace memories of pogroms Soutine had witnessed in Russia as a child? The most famous of these events occurred in 1903, in Kishinev, close to Belarus where the 10-year-old Soutine lived at the time. Or were they a prophecy of what was to come?

The other image this painting triggered for me was a piece of flesh the Mole eats in Kafka’s unfinished story, “The Burrow.” “I choose a lovely piece of flayed red flesh and creep with it into one of the heaps of earth.”

Still life had traditionally evoked beauty and calm, or been used to display a patron’s wealth. How far removed Soutine is from that tradition which goes back to 18th-century masters like Luis Melendez and Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin. Even in the 20th century he was out of step. Contemporaries like Paul Klee painted still lifes, but usually to create new color relationships in abstracted compositions.

A little less than two months later, with images of l’Orangerie Soutines still in mind, I went to see Flesh at the Jewish Museum. The exhibit started tamely enough with “Fish, Peppers, Onions,” 1919, one of the 50 Soutine paintings Alfred Barnes acquired in 1922, which changed the artist’s economic and professional situation.

But nearby, out of the corner of my eye, I could see the disturbing Still Life with Herrings, 1916.

Although it seemed a take-off on Manet’s “Still Life With Asparagus,” 1880, the Manet is charming and suave where the Soutine is intense and murderous. The two simple forks hovering above the distraught herrings have been transformed into instruments of torture. Either the small fish are dead, or with open mouths in the act of dying. The words “still life” imply life, but I thought this painting, like many of the others, was about death.

In the next room were three of Soutine’s carcass paintings (the walls quietly colored in muted tones to better accentuate each picture). The brilliant hang allowed the viewer to see each work separately and then the three together. To my eye the Albright-Knox gallery painting, ‘Carcass of Beef,’ 1925, outdid the other versions.

A lot has been written about the fresh blood on the carcass. But this painting again brought to mind “In the Penal Colony.” Unlike Rembrandt’s more sedate and distant rendering of the same subject, the bloody carcass appears recently slaughtered. In the Kafka story the killing machine called the Harrow operates while everyone watches. Although there is no trial, the victim’s guilt “is never doubted,” suggesting the way Jews were rounded up and brought to death camps for no crime only two decades after the original “Penal Colony” was written.

In Kafka’s story only one drawback is stated: “that it gets so messy.”

I found the “Hanging Turkey” nearby equally terrifying. In this image of decapitation, we witness the fowl meeting its end. Has it committed suicide or has it been murdered? With decidedly humanoid features it looks to be simply another victim. (One marvels at the possibility that art dealers of the time might have been trying to sell these works to collectors.) Another fowl picture shows dead pheasants on a moving table swirling in a room. Painted four years after the death of Marcel Proust, it reminded me of a scene of inebriation from his In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower:

Several of the waiters who served, let loose between the tables, flying at all speed, had on their extended palms a plate of which the goal of this kind of career seemed to be to not let it fall … I looked at the round tables whose innumerable assemblages filled the restaurant, like so many planets, such as those that are figured in allegorical paintings of former times.

The exhibition’s last room featured work from the 1930s and ’40s. The pictures were more “realistic” depictions of their subjects, not given over to parable or analogy.

“Duck Pond at Champigny,” 1943, was the one classical landscape in the exhibition, and would have been difficult to attribute to Soutine. The wall card stated that it had been painted a month before his death. The rich and cool picture emits a feeling of memory of days past. Close to the middle of its glistening surface sits a tree trunk with a red dot.

“This one must have to do with Courbet,” I said to my son with me that day. (I knew that Courbet along with Rembrandt had been favorites of Soutine.)

Suddenly a man came up from behind. I had been oblivious to my surroundings, but apparently, he’d been listening in on our conversation.

“The red dot has nothing to do with Courbet,” he said. “It refers to Camille Corot. In Corot’s landscapes there is often a red dot. In fact, on the back of the picture it says ‘Homage to Camille Corot.’ ”

I was very surprised. “How do you know what’s on the back of the picture?” I asked.

“Because I curated the exhibition,” he answered. I realized this was Stephen Brown, the curator of the Flesh exhibition.

When I thought about it later I felt that Kafka and Soutine, although from different countries, backgrounds, and educations, had been able to express the same sense of foreboding that every Jew carries inside herself, passed down from one generation to the next: That everything could end horribly in just one moment—that, for us, possible annihilation always lurks around the corner. As a result, these two twinned geniuses were able to prophesy the horrible truth of what was to come.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Pat Lipsky is a Color Field painter and writer.