The State of Emergency as a Paradigm of Government

Is the ‘state of exception’ now the rule?

The essential contiguity between the state of exception and sovereignty was established by Carl Schmitt in his book Politische Theologie (1922). Although his famous definition of the sovereign as “he who decides on the state of exception” has been widely commented on and discussed, there is still no theory of the state of exception in public law, and jurists and theorists of public law seem to regard the problem more as a quaestio facti than as a genuine juridical problem. Not only is such a theory deemed illegitimate by those authors who (following the ancient maxim according to which necessitas legem non habet [necessity has no law]) affirm that the state of necessity, on which the exception is founded, cannot have a juridical form, but it is difficult even to arrive at a definition of the term given its position at the limit between politics and law. If exceptional measures are the result of periods of political crisis and, as such, must be understood on political and not juridico-constitutional grounds, then they find themselves in the paradoxical position of being juridical measures that cannot be understood in legal terms, and the state of exception appears as the legal form of what cannot have legal form.

One of the elements that make the state of exception so difficult to define is certainly its close relationship to civil war, insurrection, and resistance. Because civil war is the opposite of normal conditions, it lies in a zone of undecidability with respect to the state of exception, which is state power’s immediate response to the most extreme internal conflicts. Thus, over the course of the 20th century, we have been able to witness a paradoxical phenomenon that has been effectively defined as a “legal civil war.”

Let us take the case of the Nazi state. No sooner did Hitler take power (or, as we should perhaps more accurately say, no sooner was power given to him) than, on Feb. 28, he proclaimed the Decree for the Protection of the People and the State, which suspended the articles of the Weimar Constitution concerning personal liberties. The decree was never repealed, so that from a juridical standpoint the entire Third Reich can be considered a state of exception that lasted 12 years. In this sense, modern totalitarianism can be defined as the establishment, by means of the state of exception, of a legal civil war that allows for the physical elimination not only of political adversaries but of entire categories of citizens who for some reason cannot be integrated into the political system.

Since then, the voluntary creation of a permanent state of emergency (though perhaps not declared in the technical sense) has become one of the essential practices of contemporary states, including so-called democratic ones. Faced with the unstoppable progression of what has been called a “global civil war,” the state of exception tends increasingly to appear as the dominant paradigm of government in contemporary politics. This transformation of a provisional and exceptional measure into a technique of government threatens radically to alter—in fact, has already palpably altered—the structure and meaning of the traditional distinction between constitutional forms. Indeed, from this perspective, the state of exception appears as a threshold of indeterminacy between democracy and absolutism.

Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence prefers to speak here of “fancied emergency.” For their part, Nazi jurists spoke openly of a gewollte Ausnahmezustand, a “willed state of exception,” “for the sake of establishing the National Socialist State.”

The immediately biopolitical significance of the state of exception as the original structure in which law encompasses living beings by means of its own suspension emerges clearly in the “military order” issued by the president of the United States on Nov. 13, 2001, which authorized the “indefinite detention” and trial by “military commissions” (not to be confused with the military tribunals provided for by the law of war) of noncitizens suspected of involvement in terrorist activities.

The USA Patriot Act issued by the U.S. Senate on Oct. 26, 2001, already allowed the attorney general to “take into custody” any alien suspected of activities that endangered “the national security of the United States,” but within seven days the alien had to be either released or charged with the violation of immigration laws or some other criminal offense. What was new about President Bush’s order was that it radically erases any legal status of the individual, thus producing a legally unnamable and unclassifiable being. Not only do the Taliban captured in Afghanistan not enjoy the status of POWs as defined by the Geneva Convention, they do not even have the status of persons charged with a crime according to American laws. Neither prisoners nor persons accused, but simply “detainees,” they are the object of a pure de facto rule, of a detention that is indefinite not only in the temporal sense but in its very nature as well, since it is entirely removed from the law and from judicial oversight.

Between 1934 and 1948, in the face of the collapse of Europe’s democracies, the theory of the state of exception (which had made a first, isolated appearance in 1921 with Schmitt’s book Dictatorship) saw a moment of particular fortune, but it is significant that this occurred in the pseudomorphic form of a debate over so-called constitutional dictatorship. This term (which German jurists had already used to indicate the emergency [eccezionali] powers that Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution granted the president of the Reich [Hugo Preuss: Reichsverfassungsmäßige Diktatur]) was taken up again and developed by Frederick M. Watkins (“The Problem of Constitutional Dictatorship,” 1940), Carl J. Friedrich (Constitutional Government and Democracy, [1941] 1950), and finally Clinton L. Rossiter (Constitutional Dictatorship: Crisis Government in the Modern Democracies, 1948). Before them, we must also at least mention the book by the Swedish jurist Herbert Tingsten, Les pleins pouvoirs. L’expansion des pouvoirs gouvernementaux pendant et après la Grande Guerre (1934).

While these books are quite varied and as a whole more dependent on Schmitt’s theory than a first reading might suggest, they are nevertheless equally important because they record for the first time how the democratic regimes were transformed by the gradual expansion of the executive’s powers during the two world wars and, more generally, by the state of exception that had accompanied and followed those wars. They are in some ways the heralds who announced what we today have clearly before our eyes—namely, that since “the state of exception ... has become the rule” (Benjamin 1942), it not only appears increasingly as a technique of government rather than an exceptional measure, but it also lets its own nature as the constitutive paradigm of the juridical order come to light.

Tingsten’s analysis centers on an essential technical problem that profoundly marks the evolution of the modern parliamentary regimes: the delegation contained in the “full powers” laws mentioned above, and the resulting extension of the executive’s powers into the legislative sphere through the issuance of decrees and measures. “By ‘full powers laws’ we mean those laws by which an exceptionally broad regulatory power is granted to the executive, particularly the power to modify or abrogate by decree the laws in force.” Because laws of this nature, which should be issued to cope with exceptional circumstances of necessity or emergency, conflict with the fundamental hierarchy of law and regulation in democratic constitutions and delegate to the executive a legislative power that should rest exclusively with parliament, Tingsten seeks to examine the situation that arose in a series of countries (France, Switzerland, Belgium, the United States, England, Italy, Austria, and Germany) from the systematic expansion of executive powers during World War I, when a state of siege was declared or full powers laws issued in many of the warring states (and even in neutral ones, like Switzerland). The book goes no further than recording a large number of case histories; nevertheless, in the conclusion the author seems to realize that although a temporary and controlled use of full powers is theoretically compatible with democratic constitutions, “a systematic and regular exercise of the institution necessarily leads to the ‘liquidation’ of democracy.”

From this perspective, WWI (and the years following it) appear as a laboratory for testing and honing the functional mechanisms and apparatuses of the state of exception as a paradigm of government. One of the essential characteristics of the state of exception—the provisional abolition of the distinction among legislative, executive, and judicial powers—here shows its tendency to become a lasting practice of government.

Friedrich’s book makes much more use than is apparent of Schmitt’s theory of dictatorship, which is dismissed in a footnote as “a partisan tract.” Schmitt’s distinction between commissarial dictatorship and sovereign dictatorship reappears here as an opposition between constitutional dictatorship, which seeks to safeguard the constitutional order, and unconstitutional dictatorship, which leads to its overthrow. The impossibility of defining and overcoming the forces that determine the transition from the first to the second form of dictatorship (which is precisely what happened, for example, in Germany) is the fundamental aporia of Friedrich’s book, as it is generally of all theories of constitutional dictatorship. All such theories remain prisoner in the vicious circle in which the emergency measures they seek to justify in the name of defending the democratic constitution are the same ones that lead to its ruin.

In Rossiter’s book these aporias explode into open contradictions. Unlike Tingsten and Friedrich, Rossiter explicitly seeks to justify constitutional dictatorship through a broad historical examination. His hypothesis here is that because the democratic regime, with its complex balance of powers, is conceived to function under normal circumstances, “in time of crisis a democratic, constitutional government must temporarily be altered to whatever degree is necessary to overcome the peril and restore normal conditions. This alteration invariably involves government of a stronger character; that is, the government will have more power and the people fewer rights.” Rossiter is aware that constitutional dictatorship (that is, the state of exception) has, in fact, become a paradigm of government (“a well-established principle of constitutional government”) and that as such it is fraught with dangers; nevertheless, it is precisely the immanent necessity of constitutional dictatorship that he intends to demonstrate. But as he makes this attempt, he entangles himself in irresolvable contradictions.

Indeed, Schmitt’s model (which he judges to be “trail-blazing, if somewhat occasional,” and which he seeks to correct), in which the distinction between commissarial dictatorship and sovereign dictatorship is not one of nature but of degree (with the decisive figure undoubtedly being the latter), is not so easily overcome. Although Rossiter provides no fewer than 11 criteria for distinguishing constitutional dictatorship from unconstitutional dictatorship, none of them is capable either of defining a substantial difference between the two or of ruling out the passage from one to the other. The fact is that the two essential criteria of absolute necessity and temporariness (which all the others come down to in the last analysis) contradict what Rossiter knows perfectly well, that is, that the state of exception has by now become the rule.

The only legal apparatus in England that is comparable to the French état de siège goes by the term martial law; but this concept is so vague that it has been rightly described as an “unlucky name for the justification by the common law of acts done by necessity for the defence of the Commonwealth when there is war within the realm.” This, however, does not mean that something like a state of exception could not exist. In the Mutiny Acts, the crown’s power to declare martial law was generally confined to times of war; nevertheless, it necessarily entailed sometimes serious consequences for the civilians who found themselves factually involved in the armed repression. Thus Schmitt sought to distinguish martial law from the military tribunals and summary proceedings that at first applied only to soldiers, in order to conceive of it as a purely factual proceeding and draw it closer to the state of exception: “Despite the name it bears, martial law is neither a right nor a law in this sense, but rather a proceeding guided essentially by the necessity of achieving a certain end.”

WWI played a decisive role in the generalization of exceptional executive apparatuses in England as well. Indeed, immediately after war was declared, the government asked parliament to approve a series of emergency measures that had been prepared by the relevant ministers, and they were passed virtually without discussion. The most important of these acts was the Defence of the Realm Act of Aug. 4, 1914, known as DORA, which not only granted the government quite vast powers to regulate the wartime economy, but also provided for serious limitations on the fundamental rights of the citizens (in particular, granting military tribunals jurisdiction over civilians). The activity of parliament saw a significant eclipse for the entire duration of the war, just as in France. And in England, too, this process went beyond the emergency of the war, as is shown by the approval—on Oct. 29, 1920, in a time of strikes and social tensions—of the Emergency Powers Act. Indeed, Article 1 of the act stated that:

[i]f at any time it appears to His Majesty that any action has been taken or is immediately threatened by any persons or body of persons of such a nature and on so extensive a scale as to be calculated, by interfering with the supply and distribution of food, water, fuel, or light, or with the means of locomotion, to deprive the community, or any substantial portion of the community, of the essentials of life, His Majesty may, by proclamation (hereinafter referred to as a proclamation of emergency), declare that a state of emergency exists.

Article 2 of the law gave His Majesty in Council the power to issue regulations and to grant the executive the “powers and duties ... necessary for the preservation of the peace,” and it introduced special courts (“courts of summary jurisdiction”) for offenders. Even though the penalties imposed by these courts could not exceed three months in jail (“with or without hard labor”), the principle of the state of exception had been firmly introduced into English law.

The place—both logical and pragmatic—of a theory of the state of exception in the American Constitution is in the dialectic between the powers of the president and those of Congress. This dialectic has taken shape historically (and in an exemplary way already beginning with the Civil War) as a conflict over supreme authority in an emergency situation; or, in Schmittian terms (and this is surely significant in a country considered to be the cradle of democracy), as a conflict over sovereign decision.

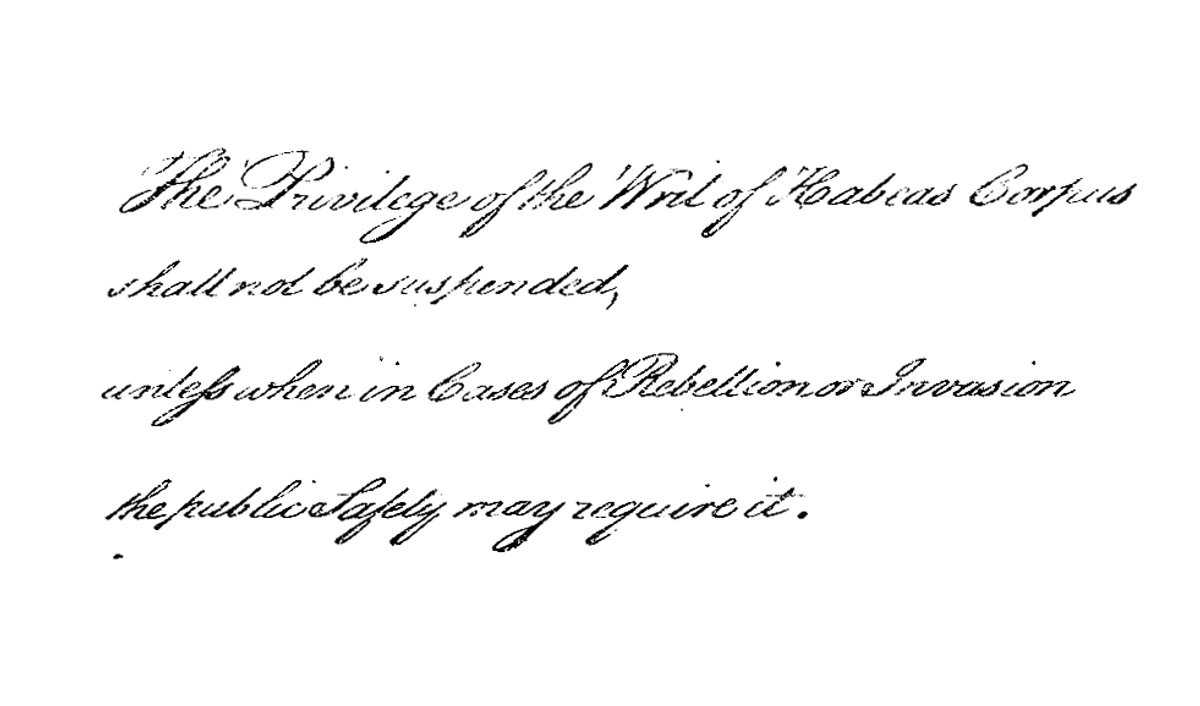

The textual basis of the conflict lies first of all in Article 1 of the Constitution, which establishes that “[t]he Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it,” but does not specify which authority has the jurisdiction to decide on the suspension (even though prevailing opinion and the context of the passage itself lead one to assume that the clause is directed at Congress and not the president).

The second point of conflict lies in the relation between another passage of Article 1 (which declares that the power to declare war and to raise and support the army and navy rests with Congress) and Article 2, which states that “[t]he President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States.”

Both of these problems reach their critical threshold with the Civil War (1861–1865). Acting counter to the text of Article 1, on April 15, 1861, Lincoln decreed that an army of 75,000 men was to be raised and convened a special session of Congress for July 4. In the 10 weeks that passed between April 15 and July 4, Lincoln in fact acted as an absolute dictator (for this reason, in his book Dictatorship, Schmitt can refer to it as a perfect example of commissarial dictatorship).

On April 27, with a technically even more significant decision, Lincoln authorized the general in chief of the Army to suspend the writ of habeas corpus whenever he deemed it necessary along military lines between Washington and Philadelphia, where there had been disturbances. Furthermore, the president’s autonomy in deciding on extraordinary measures continued even after Congress was convened (thus, on Feb. 14, 1862, Lincoln imposed censorship of the mail and authorized the arrest and detention in military prisons of persons suspected of “disloyal and treasonable practices”).

In the speech he delivered to Congress when it was finally convened on July 4, the president openly justified his actions as the holder of a supreme power to violate the Constitution in a situation of necessity. “Whether strictly legal or not,” he declared, the measures he had adopted had been taken “under what appeared to be a popular demand and a public necessity” in the certainty that Congress would ratify them. They were based on the conviction that even fundamental law could be violated if the very existence of the union and the juridical order were at stake (“Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated?”).

It is obvious that in a wartime situation the conflict between the president and Congress is essentially theoretical. The fact is that although Congress was perfectly aware that the constitutional jurisdictions had been transgressed, it could do nothing but ratify the actions of the president, as it did on Aug. 6, 1861.

Strengthened by this approval, on Sept. 22, 1862, the president proclaimed the emancipation of the slaves on his authority alone and, two days later, generalized the state of exception throughout the entire territory of the United States, authorizing the arrest and trial before courts martial of “all Rebels and Insurgents, their aiders and abettors within the United States, and all persons discouraging volunteer enlistments, resisting militia drafts, or guilty of any disloyal practice, affording aid and comfort to Rebels against the authority of the United States.” By this point, the president of the United States was the holder of the sovereign decision on the state of exception.

According to American historians, during WWI President Woodrow Wilson personally assumed even broader powers than those Abraham Lincoln had claimed. It is, however, necessary to specify that instead of ignoring Congress, as Lincoln had done, Wilson preferred each time to have the powers in question delegated to him by Congress. In this regard, his practice of government is closer to the one that would prevail in Europe in the same years, or to the current one, which instead of declaring the state of exception prefers to have exceptional laws issued. In any case, from 1917 to 1918, Congress approved a series of acts (from the Espionage Act of June 1917 to the Overman Act of May 1918) that granted the president complete control over the administration of the country and not only prohibited disloyal activities (such as collaboration with the enemy and the diffusion of false reports), but even made it a crime to “willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States.”

Because the sovereign power of the president is essentially grounded in the emergency linked to a state of war, over the course of the 20th century the metaphor of war becomes an integral part of the presidential political vocabulary whenever decisions considered to be of vital importance are being imposed. Thus, in 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt was able to assume extraordinary powers to cope with the Great Depression by presenting his actions as those of a commander during a military campaign:

I assume unhesitatingly the leadership of this great army of our people dedicated to a disciplined attack upon our common problems. ... I am prepared under my constitutional duty to recommend the measures that a stricken Nation in the midst of a stricken world may require. ... But in the event that the Congress shall fail to take [the necessary measures] and in the event that the national emergency is still critical, I shall not evade the clear course of duty that will then confront me. I shall ask the Congress for the one remaining instrument to meet the crisis—broad Executive power to wage war against the emergency, as great as the power that would be given to me if we were in fact invaded by a foreign foe.

It is well not to forget that, from the constitutional standpoint, the New Deal was realized by delegating to the president (through a series of statutes culminating in the National Recovery Act of June 16, 1933) an unlimited power to regulate and control every aspect of the economic life of the country—a fact that is in perfect conformity with the already mentioned parallelism between military and economic emergencies that characterizes the politics of the 20th century.

The outbreak of WWII extended these powers with the proclamation of a “limited” national emergency on Sept. 8, 1939, which became unlimited on May 27, 1941. On Sept. 7, 1942, while requesting that Congress repeal a law concerning economic matters, the president renewed his claim to sovereign powers during the emergency: “In the event that the Congress should fail to act, and act adequately, I shall accept the responsibility, and I will act. ... The American people can ... be sure that I shall not hesitate to use every power vested in me to accomplish the defeat of our enemies in any part of the world where our own safety demands such defeat.” The most spectacular violation of civil rights (all the more serious because of its solely racial motivation) occurred on Feb. 19, 1942, with the internment of 70,000 American citizens of Japanese descent who resided on the West Coast (along with 40,000 Japanese citizens who lived and worked there).

President Bush’s decision to refer to himself constantly as the “Commander in Chief of the Army” after Sept. 11, 2001, must be considered in the context of this presidential claim to sovereign powers in emergency situations. If, as we have seen, the assumption of this title entails a direct reference to the state of exception, then Bush is attempting to produce a situation in which the emergency becomes the rule, and the very distinction between peace and war (and between foreign and civil war) becomes impossible.

We find an implicit critique of the state of exception in Dante’s De monarchia. Seeking to prove that Rome gained dominion over the world not through violence but iure, Dante states that it is impossible to obtain the end of law (that is, the common good) without law, and that therefore “whoever intends to achieve the end of law, must proceed with law [quicunque finem iuris intendit cum iure graditur]” (2.5.22). The idea that a suspension of law may be necessary for the common good is foreign to the medieval world.

It is only with the moderns that the state of necessity tends to be included within the juridical order and to appear as a true and proper “state” of the law.

Reprinted with permission from State of Exception, by Giorgio Agamben, translated by Kevin Attell, published by the University of Chicago Press. © 2005. All rights reserved.

Giorgio Agamben, an Italian philosopher, is the author most recently of the nine-volume Homo Sacer series.