String Theory

Artist Ben Schachter puzzles over boundaries, real and imagined

A thin string stretching down and across city streets, high above the traffic, jumping from telephone pole to lamppost to fence, an eruv always has the air of an art installation. Paradoxically one of the most obscure and one of the most visible Jewish religious objects, the eruv allows observant Jews to carry their possessions (and children) on the Sabbath. While carrying in public spaces is generally forbidden as a form of work, carrying within one’s home is permitted. By erecting what is in essence a minimally defined wall, one extends the theoretical boundaries of one’s home to an entire neighborhood.

But while walls are usually solid, eruvs are elusive in form and meaning. During the Sabbath, their integrity is so vital that community members must inspect each segment regularly. But at the end of that 25-hour day, only the eruv’s physical form remains—and hardly that. My third-story windows look out directly at an eruv at eye level, and from time to time as the day passes, I search for it. It takes concentration and patience, just as one’s eyes must adjust to see stars in the night sky. It vanishes and reappears as the light changes.

The eruv’s elusiveness intrigued the artist Ben Schachter, who three years ago decided to create a series of artworks based on the eruv and in the process discovered a set of ideas that have animated his work ever since. Schachter’s eruv series consists of blue thread stitched into paper, filled in with white acrylic paint: outlines of the eruv-bounded neighborhoods that Schachter has passed through. The form is simple, but when we look at the work, we contemplate the nature of boundaries in our lives, the ways we translate our ideals and goals into the material, the limits of community, the size of our personal universe.

Just as these large concerns can be embodied in a single pure line, the eruv is also the final result of a substantial, complex body of rabbinic rulings. This imbalance between process and product is one of the chief characteristics that drew Schachter to the eruv, because it would link his work with that of his intellectual and aesthetic forebears, the conceptual artists of the 1960s, who used rules and instructions to set an idea in motion and let it run its course.

“The idea becomes a machine that makes the art,” Sol LeWitt wrote in 1967. For LeWitt, whose work particularly inspires Schachter, this concept flowed in part from an interest in the working process of architects, who rely on draftsmen and builders to carry out their visions. LeWitt, who as a young man worked for the architect I.M. Pei, tried to recreate that indirect style of art-making, drafting intricate but ambiguous instructions for wall drawings that his assistants would assemble. Schachter hoped to follow this model, but he felt that his work would be enriched if he based it on a set of existing rules, with its own external significance. What better culture to borrow from than his own—Judaism—with its meticulously elaborated rabbinical guidelines for the minutest aspects of everyday life?

In 2007, Schachter went to a local Judaica store and bought a bilingual edition of Tractate Eruvin—the volume of the Talmud devoted to eruvs. He studied the extensive discussions of walls and entryways, measurements and contingencies. He felt immediately that he had found what he was looking for: “Tractate Eruvin is like a 2,000-page Sol LeWitt book,” he says.

Ever since Schachter began working on his eruv series, he has been discovering other artists who are importing Jewish ideas into contemporary art in clever ways, and he had the chance to showcase some of his favorites earlier this year when he curated an exhibition called “Tzit Tzit: Fiber Art and Jewish Identity” for St. Vincent College, in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, where he teaches.

The range of artworks in the exhibit reflects a variety of Jewish experience and artistic approach, the common thread being the translation of Jewish law and Jewish experience into the material. Carol Es’s compositions consist of words and images drawn on sewing patterns; for her, the material was a reminder of her (non-Jewish) family’s labor in Los Angeles garment factories. Maya Escobar’s Shomer Negiah Panties tweaks the prohibition against touching a non-family member of the opposite sex by emblazoning the phrase “shomer negiah” across the backs of brightly colored women’s underwear; for Escobar, the fabric represents a boundary that tempts and repels.

Schachter has also played with disobedience in his own work, as in Kosher/Treif, in which he translates kashrut into the realm of the painter. Paints, after all, have for centuries been made from natural materials that sometimes double as foodstuffs. For one panel, Schachter bought certified-kosher milk and mixed his own milk paint—a rustic, ancient finish that he sees on barns in Pennsylvania, where he lives. He painted the panel white and stamped the bottom “O-U D”—the emblem of the Union of Orthodox Rabbis and the abbreviation for “dairy.” For a treif (non-kosher) meat panel, Schachter used the pigment cochineal red, a scarlet dye made from crushed insects. (Schachter is also experimenting with a series based on shatnes, the prohibition against combining linen and wool.)

But eruv art has remained at the center of Schachter’s work, in part because it allows him to explore not just one common project of contemporary art—generating art from rules—but a second: creating a line in space. Various artists, taking drawing as their starting point, have tried to lift the line from the page and bring it into the world. The minimalist sculptor Fred Sandback, who created spare three-dimensional forms by stretching strands of yarn from wall to wall and floor to ceiling, described his creations as “something both existing and not existing at the same time … a volume of air and light above the surface of the floor.” Schachter experimented with different sorts of lines in space during graduate school at the Pratt Institute in New York. He had been creating works from electrical hardware—a wall of more than 200 motion-sensing nightlights, a light-bulb chess set with each square a socket—when he hit upon the idea of making shapes out of electric cables—coiling them, looping them. An eruv was a cable whose shape was governed by rules.

Last weekend Schachter opened a new installation at the Mattress Factory, a contemporary-art museum in Pittsburgh. “The Residents of Chelm Visit the Mexican War Streets” extends Schachter’s eruv explorations into a new environment and in the process changes their meaning. Using a single continuous blue line, Schachter has drawn a cityscape of the museum’s own neighborhood (whose streets are named for the battles and generals of the Mexican-American War), tracing it onto the gallery’s windows and resin panels suspended in front of them by blue wire. This line is not a boundary but a meandering gesture that encompasses the neighborhood in all its detail—an inclusive, humanist line replacing the exclusive, rule-bound one.

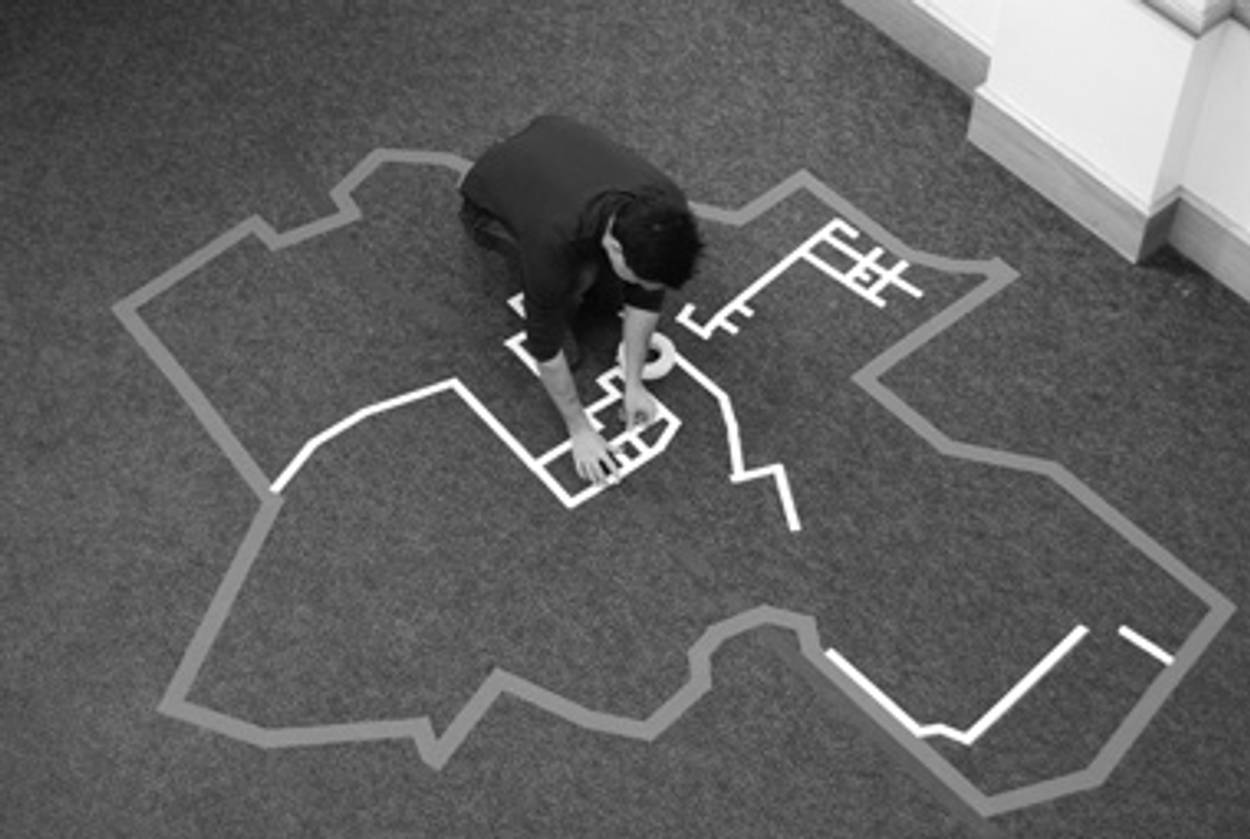

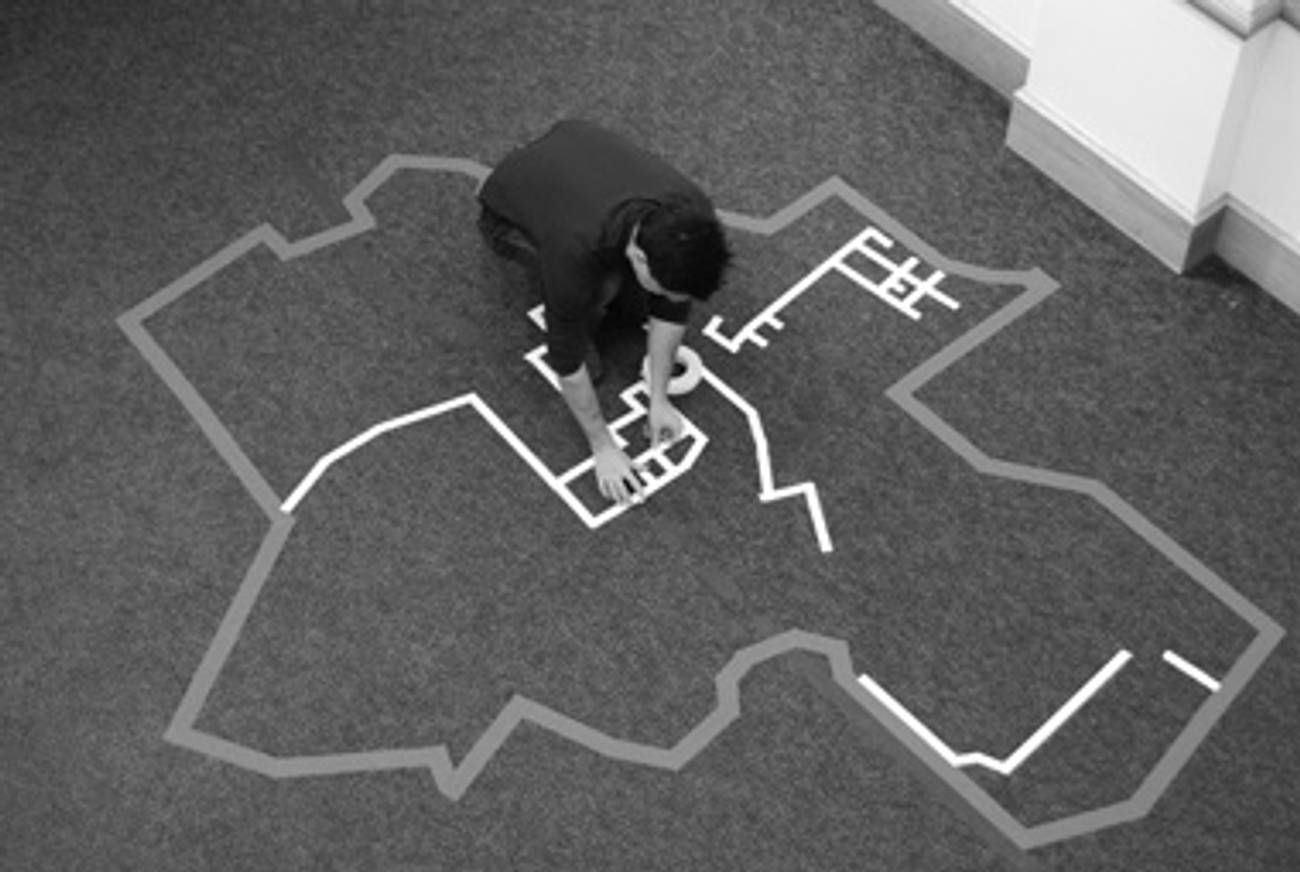

This evolution was already evident in a work called Fences that Schachter displayed at the American Jewish Museum in Pittsburgh last year. Visitors to that exhibit were asked to write down words and phrases that defined how they understood their home, community, and neighborhood. Over time, Schachter added these to the exhibit by stitching borrowed words and scenes into paper. People also wrote down local places and routes that meant something to them, which Schachter would add to a rough map in colored tape that he had created on the gallery’s floor. Schachter’s impulse to involve other people in his art-making is quite different from LeWitt’s: Schachter is looking for collaborators rather than instruments. Perhaps the best example of Schachter’s humanism is his “Instant Eruv”—eruv achshav—nothing more than a coil of hot-pink thread in a plastic bag with a price tag, as if to say, go out and make your own art and your own community. Instructions are not included.

Joshua J. Friedman, a former editor at The Atlantic and the Boston Review, is a writer in New York City.

Joshua J. Friedman, a former editor at The Atlantic and the Boston Review, is a writer in New York City.