It’s impossible to find an English-language copy of Réjean Ducharme’s 1966 debut novel The Swallower Swallowed (L’Avaleé des avalés, in the original French) for sale in New York City. You can read it in the main reading room of the New York Public Library’s central branch, but you can’t take it out. Consequently, reading the book has become a kind of installation art piece: an intern puts your request ticket in a canister and shoots it down a tube, and when you receive the little orange 1968 translation by Barbara Bray—the first and only British edition—you try to swallow it whole, in a single sitting, in a 297-foot-long marble hall, beneath 52-foot ceilings and gargantuan windows. It’s as if this was Ducharme’s design; the novel is about the refusal to be confined, to dwell in any but the most grandiose spaces, to be placed within a category or submit to bonds. But this sounds like Ayn Rand bilge, and Ducharme treats such refusal as a quixotic, deeply problematic compulsion, rather than the keystone of a political philosophy.

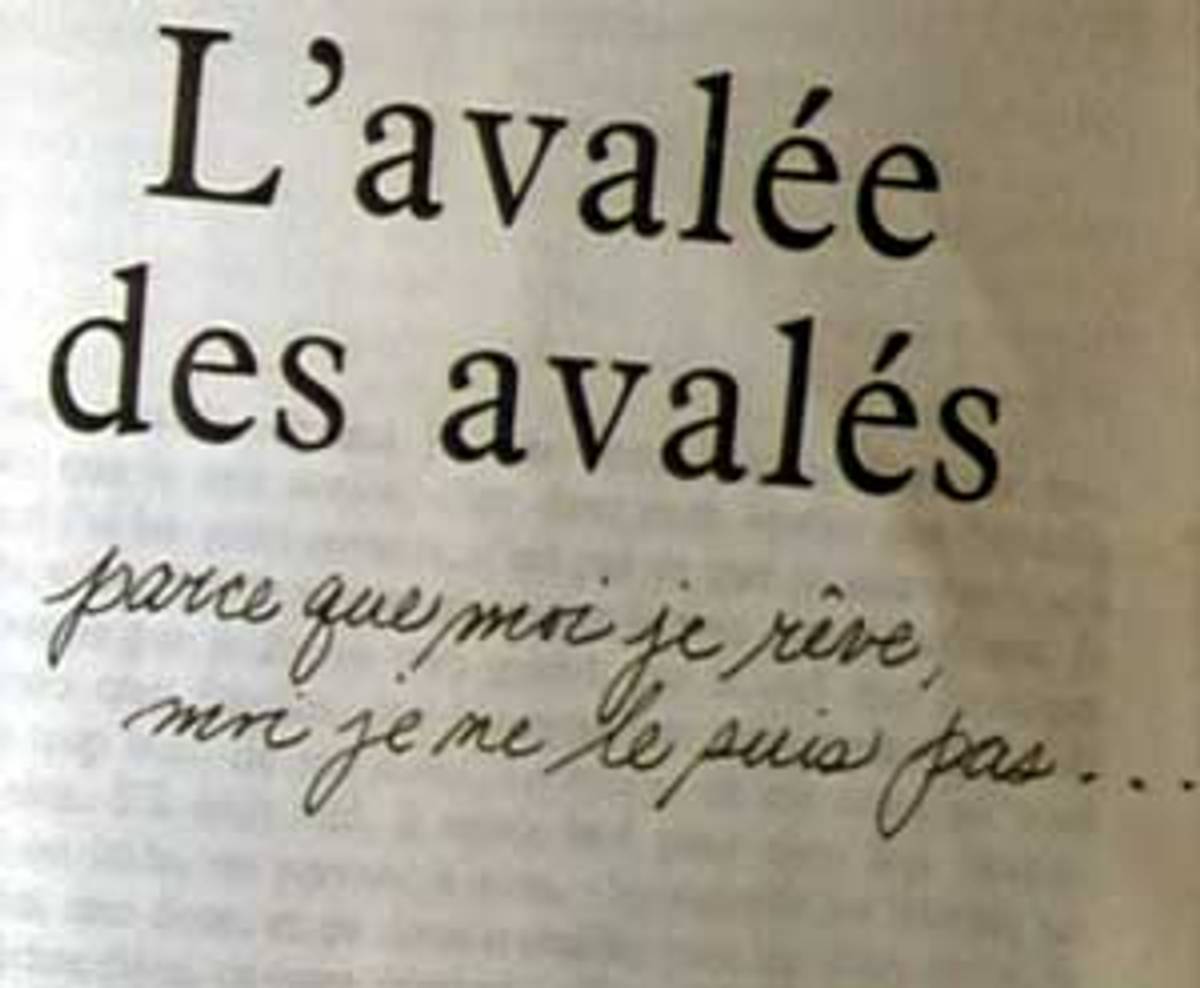

Born in Quebec in 1941, Ducharme dropped out of Ecole Polytechnique, Montreal’s biggest engineering school, after one year. The Swallower Swallowed was published when he was 25, and his narrator, Bérénice Einberg, is alienated and precocious. Born to a rich Jewish father and a Catholic mother, Bérénice is raised a Jew in a former abbey on a wooded isle in Quebec’s Saint Lawrence River. Even as a child she feels bottomless contempt for her synagogue and her Zionist rabbi, who places her in a choir called The Children of the Children of God in Exile in Canada. She makes a religious practice of solitary dreaming, of flight from the concrete world. Parce que moi je rêve, moi je ne le suis pas, she says. I dream, therefore I am not. When grown-ups try to drag her out of her interiority, she reacts with escalating violence (in one instance, poisoning the family cat and making short work of his successor).

One may be forgiven for disliking Bérénice. But her increasingly dark depressions suggest she may not be as amoral as she thinks she is. And this is the story’s central arc: a smart, moody child of privilege slowly becomes repulsive to herself. She descends from a troubled childhood in Quebec to a miserable forced Orthodox education in New York City, and then to conscription in the Israeli army, at each phase committing viler acts. The harder she struggles, the more tightly the world coils around her.

But Bérénice’s madness for solitude is her attempt to resist another kind of madness. Anyone raised by Bérénice’s parents, Monsieur and Madame Einberg, has to take sanity into her own hands. Mauritius Einberg “rescued” his wife from a family of Nazi-sympathizers in Poland when she was 13. They quarrel over whether to raise Bérénice and her older brother, Christian, as Jews or Catholics. Moreover, they appear to have internalized the checkered history of Jewish-Polish relations:

I watch them shout at each other and hate each other so much I can see them writhing like worms in a bonfire, I can feel their teeth grinding and their heads throbbing. . . . Sometimes I enjoy it so much I burst out laughing. Hate one another, you clowns! Hurt one another and let me see you suffer a bit! Writhe a bit and make me laugh.

In these few lines, Ducharme graphs the mechanics of Bérénice’s alienation. Her necessary, self-preserving rejection of her parents leads to a yearning for isolation, a rejection of ethnic and religious identities, and a playfulness regarding the suffering of others. Even as Bérénice tries to mock her parents, she empathizes with them. She can’t merely observe their teeth grinding and their heads throbbing—she feels it. The only way out of that pain is into solitude and detachment. Bérénice is a perceptive, writerly child, one who notes that tadpoles have “throats as white and soft as a cheek.” As Thomas Mann says in Death in Venice, solitude turns us into poets even as it turns us into perverts.

Bérénice doesn’t just reject organized Judaism and her parents. She rejects love—a state of being swallowed—as entrapment and boredom: “Any life that’s a beautiful love-story is in my opinion wasted, spoiled, mediocre. It’s always the same.” When her father sends her away to live in a strict Orthodox household in New York City, the boys in her Hebrew school fall in love with her and thus bring misfortune upon themselves—she shoves one of them down the stairs and watches him bounce “like a rubber ball.” This is the mistake that gets Bérénice shipped back home to Canada, where her obsessive love for her older brother Christian, with whom she hopes to revisit the relative freedom of childhood, compels her father to ship her off to the Israeli army. There, at war with the Arabs, she commits a crime against another Jew—again, one who loves her—that makes her an anti-heroine in her own eyes, even as she lies about it. She can no longer pretend she has not been swallowed by an organization. “They believed me,” she writes of her Israeli superior officers, after dutifully giving them her alibi. “A heroine was what they needed.”

Such denunciations are more lyrical and more brutal in Ducharme’s original French. Bray, an acclaimed translator of Kristeva, Duras, and Robbe-Grillet, handles description beautifully, but gives Bérénice locutions that to a contemporary American ear signify restraint and decency, traits Bérénice does not possess. It can’t be easy to translate an enraged adolescent’s interior monologue, which may account for the discrepancy between the novel’s enthusiastic reception in French-speaking nations and its lack of renown elsewhere. In 1966 it was a finalist for France’s Prix Goncourt, and it won Canada’s Governor General’s Award in 1967; in the ’90s it inspired one internationally acclaimed Quebecois film, Jean-Claude Lauzon’s Léolo, in which the protagonist reads and quotes from it, and exerted a clear influence on a second, Léa Pool’s Emporte-Moi (“Set Me Free”). But it’s never been published in America.

This is sad, because The Swallower Swallowed dramatizes a particularly American dilemma: in our quest for independence, must we shun the confines and expectations of group identity? While Saul Bellow and Philip Roth spent the ’60s focused on the establishment of a distinctly Jewish-American voice in literature, Ducharme gave us a Jewish character obsessed with having a voice that wasn’t associated with any category—at one point in The Swallower Swallowed, Bérénice even starts her own language, “Bérénicien.” Ducharme’s project sounds more radical, loopier, more a product of its time than the work of Roth and Bellow, but his portrait of Israel as a place in which Jews engage in degrading acts of violence out of perpetual existential fear holds up well. And in hindsight, Bérénice’s refusal to make her life into a “beautiful love story” seems ahead of its time, given the state of gender relations in the early ’60s. Ducharme looked at post-war cultural institutions and decided there was a certain wisdom in a Jewish teenager locking her door and telling everyone to go away—a path that preserved integrity even as it invited madness.

From the book’s beginning, when she is about eight years old, to the end (roughly 10 years later), Bérénice doesn’t see much difference between Jews and Catholics. “It’s the same at mass as at the synagogue: everything covered in ashes and blood,” she thinks. “To be a believer means trembling like a vampire at the mention of churchyards and blood.” But Ducharme is careful to show us the particulars of the Jewish community that Bérénice scorns. From the beginning of the novel, Israel is “at war with the Arabs,” and young Jewish men decamp to Israel to fight. Her father—half self-aggrandizing, half self-loathing, and married to a Catholic—is a deeply diasporic Jew; he couldn’t be more different from the militarized Israelis who become Bérénice’s caretakers in the Jewish state. Bérénice may not care what happens to Jews in general, but Ducharme hints at a tribe being swallowed, in some sense, by the threats of the 20th century.

After the publication of The Swallower Swallowed, Ducharme retreated into the environs of Montreal and never granted interviews or appeared at public events thereafter; he seemed to have adapted the lifestyle of another bard of the alienated teenager. But unlike J.D. Salinger, Ducharme continued to publish from his northern hermitage—eight additional novels. He’s scripted three plays and two films. To this day, he exhibits his junk sculptures in Montreal galleries, under the alias Roch Plante. At the end of her story, Bérénice Einberg—finally swallowed and numbed, surrounded by soldiers who lionize her because she’s tricked them and because they want somebody to lionize—gives up both solitude and sanity. Ducharme seems to have retained some semblance of both.