Taking Stock

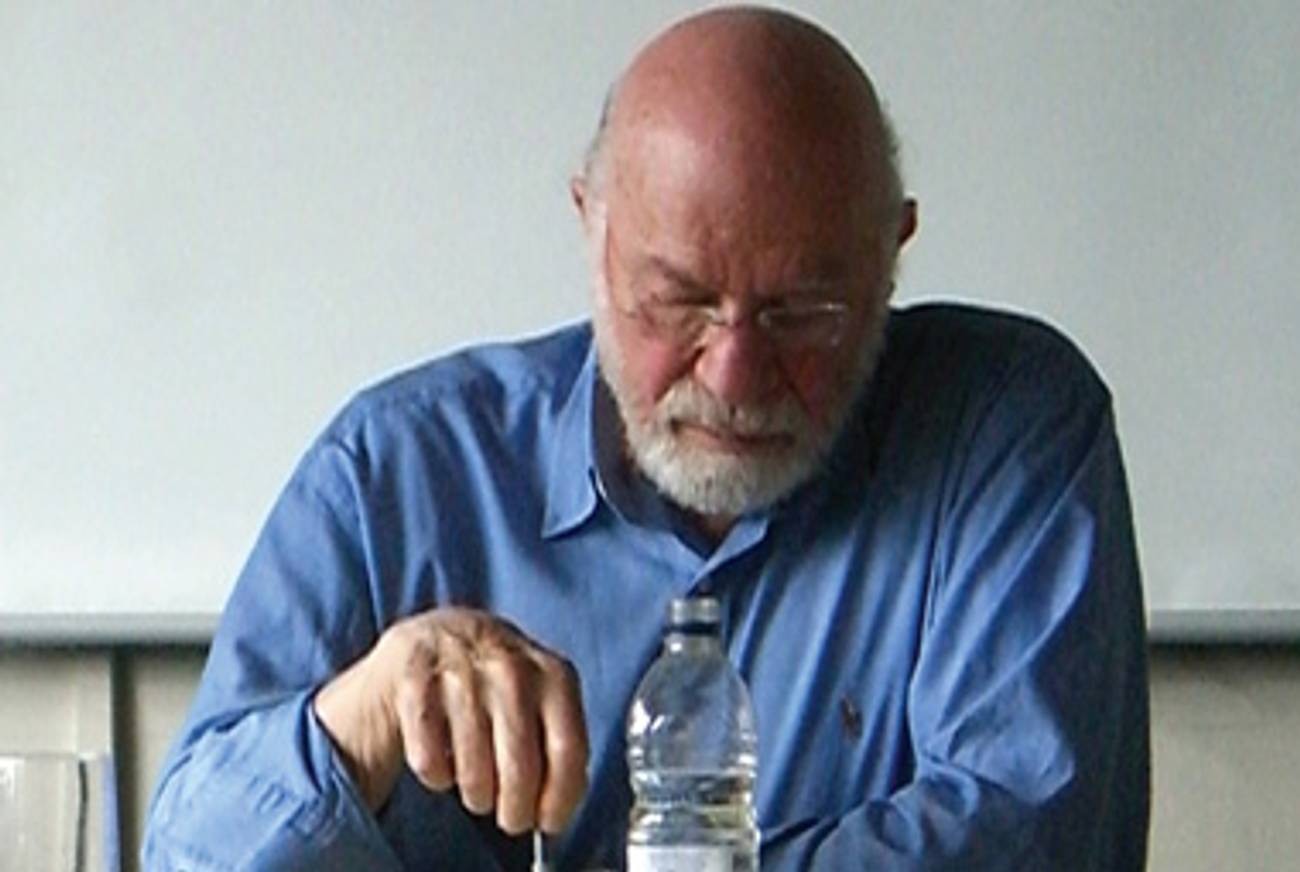

In a new memoir, philosopher Stanley Cavell reflects on what it means to be alone

At the end of his new memoir, Little Did I Know, the 84-year-old philosopher Stanley Cavell tells a story. Once, his father, then 83, woke up after heart surgery and asked about all the commotion in his hospital room. It’s ugly, his father said, to run around as if an old man’s death were really an emergency. It should stop. But who—and here the son, the philosopher, kicks in—should tell all these very professional nurses, doctors, and aides to call it off? Who is responsible for the old man’s life?

It tells us a lot about the younger man’s relation to his father, about the writer’s relation to his book, and about Cavell’s own complicated style of thought that the all-important conversation that should have taken place, didn’t. Cavell leaves it hanging. No ruminations on life and death; no dialectical exchange on duty. Instead, Cavell’s father falls asleep. The son—and Cavell is nothing if not an acute reader of Freud—goes off to find his mother. And that is that.

Cavell began writing Little Did I Know when he was about to undergo treatment for heart disease seven years ago. He saves the vignette about his father for the last pages of the book, as a kind of punch line. Cavell’s philosophy, quirky as it is, has always been about responsibility and, more important, about our tendency to avoid offering accounts of ourselves, about our unwillingness to stand by what we have done and what we should do. It is about missed connections, about our fear of paying proper attention to ourselves and the world. Little Did I Know is his accounting for himself.

It is not easy to give a brief take on Cavell, because he has always been, both figuratively and literally, all over the map. He was born in Atlanta to a musician mother and to an immigrant father (a frustrated, indifferent speaker of English who was also a frustrated and indifferent entrepreneur). The future philosopher spent his childhood traveling back and forth between business ventures his father was pursuing in Georgia and California. His father hated him; his mother loved him. He was a skilled musician, studied composition at UCLA, and did not so much flunk out of Juilliard as funk out. He got his doctorate in philosophy at Harvard, taught at Berkeley, then returned to Harvard and spent the better part of his very productive career in Cambridge. He has written both extensively and widely.

The memoir makes it tempting to cast Cavell’s career as a son’s wish to mediate between the severity of his father’s disappointments and the warmth of his mother’s creativity. After all, Cavell has spent the better part of five decades mediating between different schools of philosophy and between philosophy and the arts. He has written several books about film, and he is passionate about opera. It’s fair to say, though, that he does not just practice aesthetics, the philosophical description of the arts. One of his most stunning peculiarities is that he writes about the arts as if they were philosophy. Needless to say, Cavell’s approach doesn’t always work, but when it does, as in his 1994 article on the Marx Brothers in the London Review of Books, it can be liberating.

So, yes: Cavell is a conciliator, but to get at his insights, at his importance as an instigator, it makes sense to see him as a philosopher bent on disappointing disappointment. For Cavell, the scandal of our individuality is the source of a fundamental heartbreak. In becoming aware of ourselves, we lose the world. We doubt it and our knowledge of it.

We do not miss our appointment with the world through an error—we are indeed separate from it—but we are tempted to draw the wrong conclusions. We begin to the feel that objects as they “merely” appear to us are not what they really are, that there is something more out there. We feel that there must be a realm more real than the one we live in. Philosophy is all about this dilemma. It describes our desire to draw away from the ordinary, to locate reality elsewhere. By the same token, philosophy can try to turn us around, recover the everyday, and restore us to the pleasures of connection.

Nevertheless, our disappointment counts. It is not wrong. Things could be different, and they could be better. So, for Cavell, to return to the world does not mean accepting things as they are. To return to ourselves does not mean we should be content with our imperfections or with our discontent with them. His is a philosophy of what he calls “moral perfectionism.”

Cavell is worried about his right to say all this. How can he make such wide-ranging claims? Our individuality undermines our authority. His philosophy asks how personal experience can speak validly to and for others.

This is a tough one. We like to think of our lives in terms of their climaxes, breaks, and traumatic turns. These surprises might mark us, but they are not the stuff of the everyday. Cavell writes that “so much of what has formed me has been not events but precisely the uneventful, the nothing, the unnoted that is happening, the coloration or camouflage of the everyday.” The unnoted isn’t the stuff of story. We register it not as an event but as a mood. Mood tells us about ourselves and is our gateway to the world. It is the way that personal experience gets articulated and generalized.

So, it makes sense to read Cavell as he himself reads Emerson—as a philosopher of mood. But moods, like the tones that convey them, are hard to pin down and even harder to account for. As any reader of Marcel Proust and Henry James knows, you need a lot of space to summon forth a mood, and you need an eye for social or psychological nuance to keep things interesting. Cavell allows himself the space, but once young Stanley is out of his teens, Cavell the writer is not really that concerned with telling details. He is also too nice a guy to dish. He provides us with hundreds of pages of garrulous reticence about his friends, children, and wives, the books he has read, the books he has written, and the places he has visited. He is a bemused son and a loving father. He is the model of a grateful friend.

Gratitude is a virtue and like most virtues makes for dull reading. The most famous parts of the most famous memoirs of philosophers—Rousseau’s theft of a ribbon, Augustine’s theft of pears—turn on their vices. Sadly for the reader, Stanley Cavell is not a vicious man. He might not discuss death with his dad, but that is about as far as it goes. There is no villain in his divorce. What is more disappointing, Little Did I Know doesn’t provide us with any new or surprising insights into the turns of Cavell’s philosophy.

This is not Cavell’s first pass at autobiography. He went at it more pointedly and more concisely in 1994’s A Pitch of Philosophy. But, for all its longueurs, Little Did I Know is valuable to the extent that it makes it very clear just how much Cavell’s thinking owes to his immigrant Jewish background. The most obvious aspect of this debt—his insistence on what he calls moral perfectionism and his recourse to the theme of return—is perhaps the least intriguing. Equally obvious is the extent to which his concern with disappointment and despair is an attempt to come to terms philosophically with his father’s frustrated hopes. Cavell’s lonely childhood, his mother’s absences, and his father’s angry, angered distance must have led directly to his fascination with the ineluctable privacy of other people.

Judaism, as a sociological fact, if not a religious one, is also a form of privacy, a kind of unbridgeable separation that stands between the Jew and the outside world. This must have seemed especially true to generations of immigrants and their children. You can hear it in Cavell’s almost punctilious worry about his authority to speak and his warrant to be heard. There were plenty of Jews in Philosophy and English departments in the 1950s and the ’60s, but it couldn’t have been all that comfortable. (I know of a tenure case as recent as the 1980s in which a senior faculty member complained that a Jew couldn’t teach Shakespeare.) Jewish academics of my cohort did not experience this. In fact, with and without reason, a Jewish professor nowadays would feel comfortable claiming that Jewishness is in itself a claim for authority. The difference is telling, not the least in terms of our moods and therefore our thought.

We can learn something from Little Did I Know, but let’s be honest: There is no reason for most people to read it. For a good introduction to Cavell’s turn of mind, you might want to go to the wonderful The Senses of Walden or to his book on Hollywood comedy, Pursuits of Happiness. Cavell’s memoir does not explain his philosophy as such nor how it works out in the end. But, in its own elliptical and sometimes maddening way, it does show where the thinking came from and how it got its most salient aspect: the wisdom of its elegiac optimism, its tone of disabused affection.

David Kaufmann teaches literature at George Mason University.

David Kaufmann teaches literature at George Mason University.