Technician of the Sacred

A half-century after his groundbreaking ‘ethnopoetic’ anthology, Jerome Rothenberg’s shamanic journey into the sacred poetry of the past continues to lead him to the unknowns of poetry’s future

“Measure everything by the Titan rocket & the transistor radio, & the world is full of primitive peoples. But once change the unit of value to the poem or the dance-event or the dream… & it becomes apparent what all those people have been doing all those years with all that time on their hands,” wrote Jerome Rothenberg back in 1967, in the introduction to his groundbreaking anthology, Technicians of the Sacred. The volume became a foundation of the literary movement known as ethnopoetics, which pushed against the notion that, as Rothenberg put it, there was a single “idea of poetry, as developed in the West.” With that, the anthology brought together selections of poetry from the ancient, as well as the contemporary, “primitive” world, all the while attempting to transform the very terms it operated with. “Poetry,” “primitive,” and “anthology” came to mean something bigger and broader in Rothenberg’s work, and even the word “ancient” swelled with hues of eternal, immediate relevance.

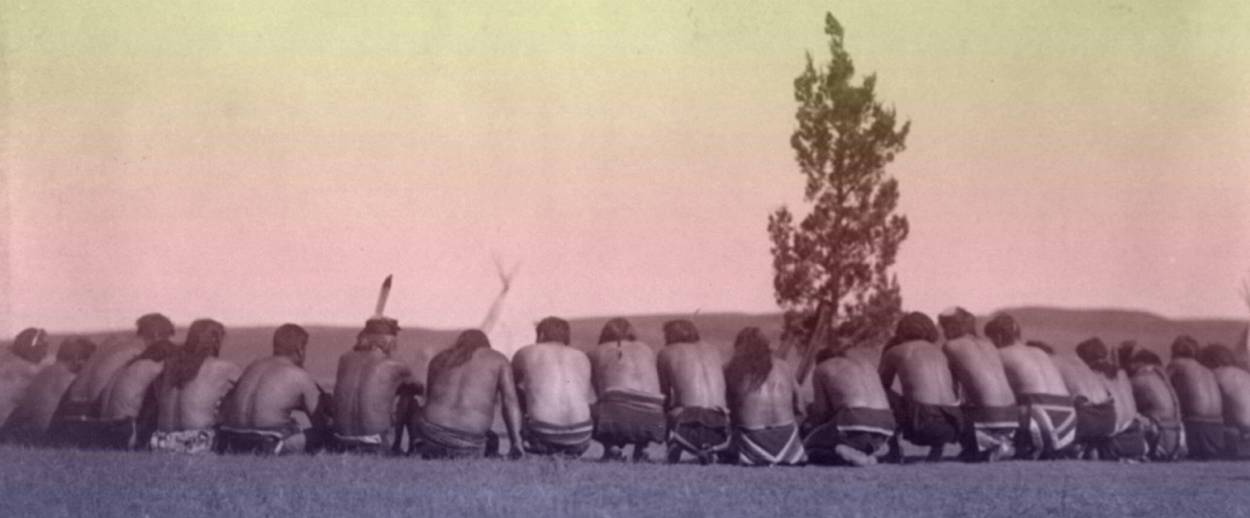

The volume’s third edition, assembled last year in honor of the 50th anniversary of the original publication, propels the conversation deeper into the 21st century and the unknown. The breakthrough insight of Technicians of the Sacred was that poetry could be drawn from ritualistic experiences, chants, incantations, and shamanic visions that originated in Africa, Asia, Oceania, or within Native American groups. Rothenberg discovered that cutting-edge avant-garde poetic advances found unexpected resonances in ancient texts. As such, he suggested that opening new possibilities for future poetry somehow allowed us, at the same time, a whole new vision of the past.

***

I teach poetry to students of all ages, and my persistent advice, all of the technical and theoretical frameworks aside, is the following: Go out and meet poets in person. Particularly poets who’ve been around long enough to witness—perhaps even to initiate—ebbs and flows of various artistic movements, and the profound cultural shifts that went along with these changes. Seeking out poets I admired and meeting them in person not only transformed me as an artist and educator, but also functioned as nexus points where my personal mythology, artistic praxis, and existential curiosity came together as spiritual, or even sacred, markers.

Jerome Rothenberg is one of the poets I sought out a number of years ago. Rothenberg published nearly 90 books—his own poetry, translations, and critically acclaimed anthologies. One such anthology, A Big Jewish Book, juxtaposes ancient mystical, mythic Jewish texts with contemporary poetry and “near-poetry” in dialogue. The volume became central to my ethos as a Jewish educator. It salvaged my relationship with the ancient texts, allowing me to put aside the dogmatic twang of many of these works and to focus on their creativity and poiesis. At the same time, all through my ongoing encounters with Rothenberg, I sought to understand what he meant when he wrote in the preface to the first reissue of Technicians that he aimed to achieve “a life lived at the level of poetry”—a tantalizing phrase that became anthemic to me.

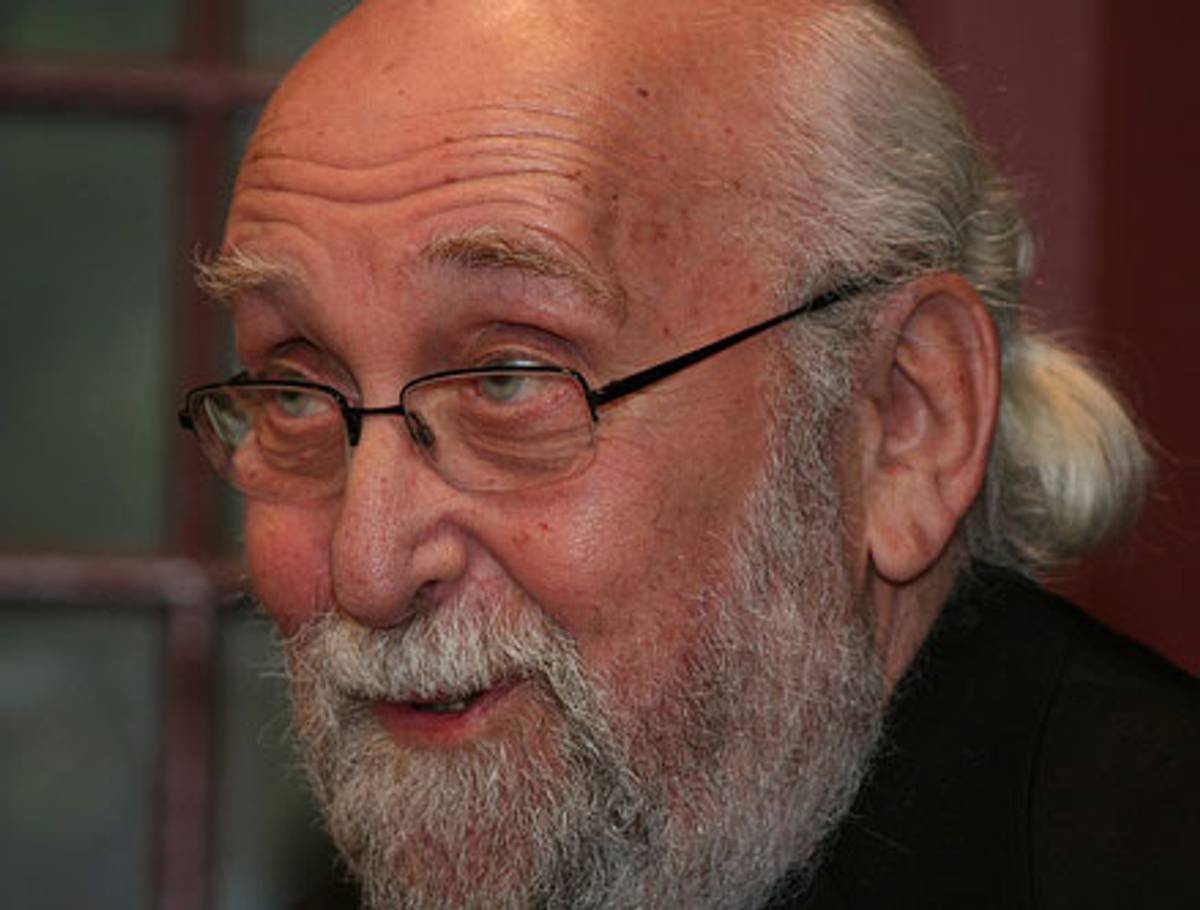

Last summer, I finally discussed the phrase with Jerome Rothenberg, as we sat in his Encinitas, California, living room. Rothenberg—gray ponytail, flip-flops—and his wife, Diane, who is a professional anthropologist and co-author, with Rothenberg, of the anthology Symposium of the Whole, are a sagacious and a generously warm presence. In answer to my question about living “at the level of poetry,” the poet described a “degree of excitement—intellectual and emotional—that could come out in other ways, of course, but comes out for me in the context of writing and performing poetry.” He added, “When I get into that frame of mind, I feel more alive, more active than in other time. I get a grip on things that don’t touch me under the ordinary circumstances. Poetry may deal with the ordinary, but in the process it becomes extraordinary; it may deal with the real, but in the process it becomes surreal.”

There’s little doubt that, to Rothenberg, poetry is far more than a prestigious publication or a memorable moment of self-expression. Here, poetry is a doorway into an alternative mind-state, an opening for thinking through one’s world in an altered, more intense fashion.

In particular, the poet pointed to his visit to Poland, which he evoked poignantly in the collection Khurbn. As he told me, “coming to Poland—which, for me, had been the imagined Poland—the actual place with its history of what had happened, particularly to the Jews of Poland, down to my own family, which had been murdered and disappeared there. I felt myself entering into a state of poetry.” It was, he said, “one of those times when you’re overwhelmed by certain experience, and there’s no language to get it said except as what I take as poetry.”

***

Challenging the established definitions of poetry is a well-worn cliché. Its outcome, more often than not, tends to be the establishing of an alternative set of new definitions and identifiers, which inevitably rigidify before long. Anthologies of breakthrough poetic visions, arranged in neat chronological (or even alphabetical) order do little to capture and perpetuate the spirit of the works’ momentum. As Rothenberg put it in the course of our conversation, “Typically anthology is an instrument for continuing and refining a sense of canonical past or canonical present. They tend to fix our ideas of poets and poetry and assert a kind of authoritativeness. But other kinds of anthologies come as manifestos, announcing a new way of looking at poetry.”

Rothenberg’s anthologies function as such manifestos—they’re alive with possibilities and questions. As he put it, “When I finish with an anthology, in my head it keeps evolving. It’s important for me to stress that the work doesn’t have an ending; it’s an ongoing work. The books don’t put an end to a project, and the project is open to anyone else who wants to do their own version.”

Instead of creating an alternative canon Rothenberg offered an ongoing project. The third edition of Technicians of the Sacred is a terrific example of this, as it expands the anthology with a wealth of new material—most notably, with a brand-new section of poems called “Survivals and Revivals.” The section contains works from Cambodia, China, Mexico, Russia, Papua New Guinea, and Chile. The project also continues on Rothenberg’s popular blog, Poems and Poetics, where he regularly posts new work by poets from around the world, oftentimes accompanied by his pithy and insightful introductions.

Yet perhaps the most innovative aspect of Technicians of the Sacred, as well as Rothenberg’s other anthologies, is the section titled “Commentaries.” It is not only a way of illuminating the offered texts, but also an opportunity to present contemporary material that resonates with the ancient work. For instance, the anthology features a text called “How Isaac Tens Became a Shaman”—an account of a mystic, belonging to the Gitxsan community, an indigenous tribe from British Columbia. The casual, entertaining, and often humorous commentary on this piece is nearly twice the size of the original text. Here, Rothenberg discusses the Siberian origins of the word “shaman”; Mircea Eliada’s famous academic treatment of shamanism as such; descriptions of the experience as they appear in the lore of various other Native American groups; and finally, the editor features excerpts from very different, but thematically resonant poems by Arthur Rimbaud, Walt Whitman, Allen Ginsberg, and Gary Snyder. These Talmudic commentaries do not merely support the main text, but attain a life of their own, swelling with polyphonies of dissent, and their own worlds.

One haunting text added to the anthology’s new “Survival and Revivals” section comes from Essie Parrish, spiritual leader of the Kashaya Pomo tribe, centered in Sonoma County, California. Parrish’s trancelike meditation was transcribed by poet George Quasha:

And there is white light, at the center

while you are walking.

This is the complicated thing:

my mind changes.

We are the people on the Earth.

We know sorrow and knowledge and faith and talent

and everything.

Now as I was walking there

some places I feel like talking

some places I feel like dancing

but I am leaving these behind for the next world.

Then when I entered into that place

I knew:

if you enter heaven

you might have to work.

This what I saw in my vision.

I don’t have to go nowhere to see.

Visions are everywhere.

Parrish’s deep swing from the personal I to the universal “people of the Earth,” from mystical “white light” to walking and dancing, from knowledge to vision, rhythm to image, is poignant poetry, historic and mythic as it is lyrical. And, it must be said, it is almost inconceivable as an entry in a more traditional contemporary-poetry anthology. Rothenberg’s work, then, his own vision, is to open the very notion of poetry to include this sort of material.

In a smaller and humbler way, my pilgrimages to great contemporary poets are, too, a work or a ritual of sorts. In the ancient days, people traveled the world over to meet the mystics. And I, too, set out one day for San Diego, watched the day’s waning on the city’s famed Sunset Cliffs, thinking through the questions I’d ask. I walked through the farmer’s market in the morning, selecting berries to bring along to my hosts. Later, as I replayed the recording of the interview with Rothenberg, his “state of poetry” immediately returned to mind—and it is not too far from me now, as I type these words.

***

Technicians of the Sacred was influential not only for the field of ethnopoetics—it also exerted influence on various individual artists of all sorts. Among numerous endorsements, the new edition carries a blurb from Rothenberg’s ardent fan, legendary musician Nick Cave, who writes: “No one taught me more about poetry than Jerome Rothenberg.” As Cave elucidated in a Wall Street Journal interview a few years ago, referring to Rothenberg’s anthology, “The primitive poetry in general, and the way it’s presented in that book is pretty extraordinary. … Just something immediate about it and visceral and shockingly erotic that gives license and a context to go other places.”

For Jerome Rothenberg, poetry does indeed serve as a context to go to other places—and not just in his imagination, but quite literally. As we sat in his living room, Jerome and Diane reflected on their recent trip to Australia for a series of readings, lectures, and encounters whereby the poet was “presented with examples from the very rich indigenous cultures, examples that could have been used in the revision” of Technicians of the Sacred.

Reflecting further on his constant traveling schedule, he added, “Traveling has been mostly ‘people travel.’ There’re going to be people on the other end, and fits in with the sense I have of poetry as a global enterprise. For some reason, I find it invigorating rather than tiring, even now. I thrive on the exchanges going into places and meeting the people. Having finished one trip, we’re looking forward to the next.”

If it is a poet’s job to redefine, even redeem words from the oblivion of mundane usage, there’s no doubt that Rothenberg’s usage of the word “global enterprise” points to the task accomplished. Referring, no doubt, to the whole world of living and dreaming readers, and their poets, Rothenberg enterprisingly repurposes the corporate phrase for his own usage—just as he yanked the word “technician,” back a half-century ago, to mean someone skilled in the technology of dreaming, writing, and evoking the sacred worldwide. Indeed, Rothenberg recalled, “As I got into the question of digging further into the roots of poetry, forms of poetry as they had existed and continued to exist in many places, I began to think of poetry as a collective work. We were all in it together.”

***

Read Jake Marmer’s poetry criticism for Tablet magazine here.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).