Tevye der Shvartzer Khazn

The story of Thomas LaRue Jones, the Black cantor from Newark who captivated the Jewish world with his songs

I came across the story of Thomas LaRue Jones by sheer accident. The year was 2015. Removed from the din that surrounded the first coming of Black Lives Matter, I was immersed in the YIVO archive in New York selecting theatrical posters for an exhibition, New York’s Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway, at the Museum of the City of New York. The names buzzing through my head were (Boris) Thomashefsky, (Jacob P.) Adler, (Maurice) Schwartz, (Molly) Picon, and other celebrities of the old Yiddish stage. Working my way through a mass of colorful theater posters that featured Yiddish divas and matinee idols, I glimpsed an old black-and-white illustrated placard with a cameolike portrait of a serious-looking young Black man with soulful eyes, dressed in festive cantorial regalia. Titled “Tevye, der shvartzer khazn” (Tevye, the Black Cantor), he was, the undated print declared, “The Greatest Wonder of the World.” A small-type English-language byline at bottom of the poster announced that “Thomas La-Rue” was “the most phenomenal cantor-tenor in America” and “the only one of his kind in the world.” “Tevye,” the renowned Black cantor, the poster announced in Yiddish, “has taken America by storm” with a multilanguage repertoire of Jewish folk songs and cantorial compositions by Yossele (Joseph) Rosenblatt and other Jewish composers.

The 1920s were an opportune time for Tevye LaRue Jones to make his entrance. Cantorial performance was flourishing in America. Cantors were no longer confined to the sacred space of the synagogue. They recorded their music, at times accompanied by musical instruments which would not be allowed in the synagogue. Even women who would not be allowed to sing in the synagogue were performing hazzones on stage. Hundreds of records of cantorial music were produced, avidly consumed by a public that was also packing concert halls and vaudeville venues where cantors performed. Outside the synagogue the cantor was no longer serving merely as a “shliakh tsibbur,” the voice of his community, but also as a seasoned entertainer whose repertoire often broadened to include folk and Yiddish theater songs. In this thriving popular Jewish culture, a Black cantor would likely prove an attraction.

So, who was this “Black Cantor”? Jones’ name does not appear in books on the Yiddish stage nor is it listed in Zalmen Zilbercweig’s comprehensive Lexicon of the Yiddish Theatre. But thanks to old, digitized newspapers, the mystery began to slowly unravel. Jones was a native of Newark, New Jersey, a city with substantial Jewish and Black communities. Endowed with a pleasant voice, the teenage Jones began a fledgling performance career singing Yiddish songs in local Jewish festive events. As early as 1915, a local Newark newspaper mentions his name, along with several other very Jewish-sounding names, as providing the entertainment for a Jewish wedding. A year later, the paper mentions his name as the person providing musical entertainment at another Jewish event.

At some point, a Jewish promoter realized the commercial potential of the young Black singer and began to organize concerts in small Jewish communities where Jones, dressed in tallit and a traditional cantor’s hat, performed Yiddish songs and cantorial music. Beginning in 1920, his name appears in ads in conjunction with various Yiddish operettas, not as a cast member but as a “special attraction” whose cantorial performance is promised to enrich the evening with “Jewish prayers.” On Sept. 6, 1921, for instance, he appeared at the Lyric theater in Allentown, Pennsylvania, with a touring Yiddish theater company that presented a melodrama titled “From Across the Sea.” A story that appeared in The Allentown Morning Call on Sept. 4, 1921, announced that in addition to actors, the company brought along Thomas LaRue Jones, introduced as “the greatest tenor singer and the only one in the world” and as “the colored Abyssinian Yiddish cantor who will sing between the acts.”

Thomas LaRue Jones was usually employed in vaudeville acts that followed popular operettas like Der Poylisher Yid (The Polish Jew) at Brooklyn’s newly constructed Liberty Theater and “The Power of Gold” at the Grand Theatre on the Lower East Side. “The Power of Gold advertisement promised, in addition to the operetta, a rich vaudeville program that included, in addition to the Black Cantor, comic skits, two English novelty acts, and Charlie Chaplin’s film The Kid. Another major production with an added Jones performance was the immensely popular comedy Tente Telebende based on the beloved sketches by B. Kovner (writer Jacob Adler) that depicted episodes starring Yente, a pesky and domineering matron who drive everyone around her crazy, especially her poor husband, Mendl. A year later, in 1923 Jones appeared in the Prospect Park Theatre in the Bronx, a “first class” Yiddish vaudeville venue where the program included the screening of Michael Strogoff, a film starring the great dramatic actor Jacob P. Adler.

LaRue Jones continued touring various Jewish communities across the country, notably Kansas City and Boston. His cantorial performances sounded so authentic to Jewish ears that some found it hard to believe that the young Black singer was gentile. A newspaper correspondent covering one of Jones’ performances admitted his sense of wonder at the Black man who was singing Yiddish songs with a genuine Jewish sigh (krechts) that tucked at the heart and penetrated the soul. He was particularly struck by LaRue’s performance of “Eli, Eli!” (My God, My God).

Not very much is known about Jones’ personal life—and what hints exist from newspaper articles and promotional materials should properly be taken with a grain of salt. LaRue told the Yiddish press that he and his sister had been raised in Newark by a Black mother who was fascinated by Judaism and Jewish books and saw to it that her children learned to pray from the siddur. Living among Jews, the children spoke fluent Yiddish and became conversant with Jewish religious customs.

In 1923 Jones came to the attention of the Afro-American newspaper, which informed readers that “La Rue Jones, a Negro of genuine racial characteristics has been discovered with the cast of a Hebrew dramatic company playing in stock at the Lenox theater, 110th and Lenox Avenue.” The paper identified him as a graduate of Newark’s high school who had his vocal training under Rabbi Moses Granspalski and received dramatic instruction by Jacob Adler. The latter, according to Jones, discovered the young Black man in an amateur school production and connected him with the Yiddish stage. The article also noted that the young man spoke Russian and Ukrainian in addition to Yiddish, and that during World War I the Department of Justice took advantage of his linguistic abilities.

The Afro-American story also mentions that Jones was performing under the “sanction of the Hebrew Actors Union.” Was he a regular member of the union which usually did not admit vaudevillians? Did he get a special dispensation from this notoriously restrictive organization? The union, established in 1900, was the first actors labor union in the world, preceding the formation of Actors Equity by two decades. In the 1920s and ’30s, it became known for its reluctance to admit new members and was often criticized for running a closed shop that made it near impossible to gain entry. The recently cataloged documents of the union, now located at the YIVO archive, include a standard form dated Feb. 2, 1937, signed by “Thomas La Rue” in which he authorizes the Hebrew Actors Union to be his “sole representative to make business and arrange bookings” in the U.S. and abroad. It is not clear if Jones’ agreement was an ad hoc arrangement or whether he indeed became a full-fledged member of the union, then governed with an iron fist by Reuben Guskin. In any case, less than three weeks after he signed this contract, on Feb. 21, the Yiddish Forward newspaper displayed an ad for a new show, Di Falshe Tokhter (The False Daughter) with a separate “special attraction!” by the “Black Cantor.” If Thomas LaRue Jones indeed became a member of the Hebrew Actors Union, he was most probably the only Black performer to gain such status.

In 1930 LaRue embarked on a tour of Europe that began in Cairo and ended in Poland, where the appearance of a Black man was a novelty for both Jews and gentiles. The Polish correspondent of the New York Forward reported that the posters of the Black cantor that were displayed around Warsaw created a sensation. As was customary, Jones visited the offices of the Jewish newspapers, where he presented himself as Reb Tevye and impressed his hosts with his flawless Yiddish and Jewish jokes.

In Poland, far from his home base, and possibly under the influence of his American promoters, LaRue Jones invented for himself an exotic origin story. He claimed he was born in Ethiopia to an old Jewish family that originated from the exiled tribes of Israel, that his father, now living in New York, was an apothecary devoted to herbal pharmacology. He, Tevye, served as cantor for the Black synagogue in Harlem which served a congregation of more than 800 people. His striking presence in Warsaw inadvertently led to two separate scandals: first among Jews, when it was revealed that he was not truly Jewish, and then among gentiles, when the sensational Polish press, not doubting his Jewishness, claimed that he was a Cohen Gadol (great priest) who adorned his head with a Star of David and his chest with a tablet with the Ten Commandments that was covered by a tallit. It also described him as a serial seducer of Jewish women, one the wife of a named local Jewish merchant, who were impressed with his royal ancestry as a descendant of a king.

Musicologist Henry Sapoznik devoted years to tracing the life and career of LaRue Jones. What he found is more mundane than the PR-driven persona presented in the press. Jones was born in Virginia, his mother died when he was very young, which places a question mark next to his sentimental account of her devotion to Judaism and her insistence on providing Jewish literacy to her two children. Also, LaRue had several, not just one sibling, two of whom worked in vaudeville.

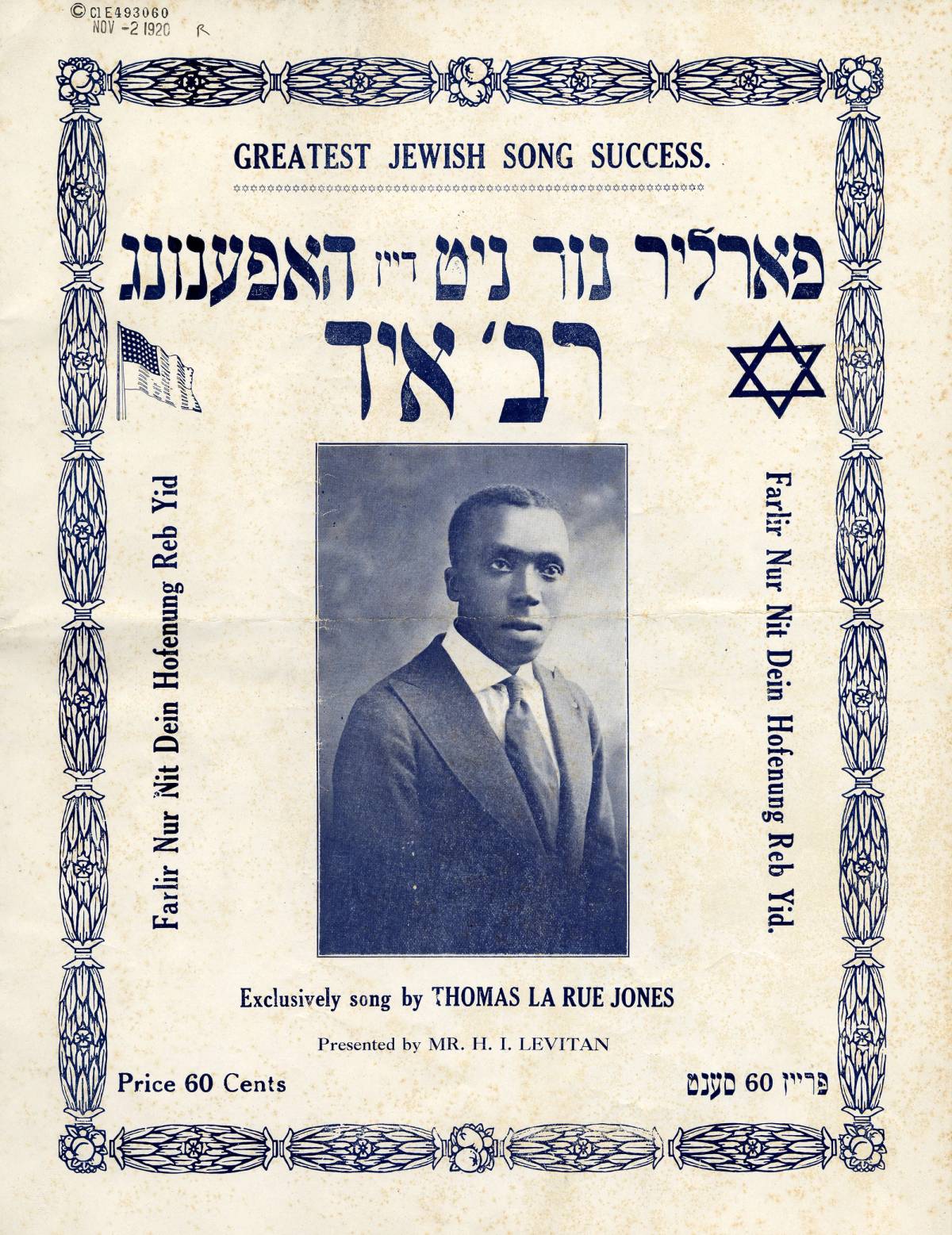

A couple of years ago, after a decadeslong search, Sapoznik located at YIVO Jones’ only known commercial record, produced in 1923 for the OKeh record label. It included a prayer of supplication from the morning service and the song “Yidele Farlier Nit Dein Hofnung,” (Jew, Do Not Lose Your Hope) written by Isidor Lash and composed by the Yiddish theater’s best-known composer Sholom Secunda (who also wrote the hit song “Bamir Bistu Sheyn”). The song recounts the sad history of the Jews and beseeches them to not give up hope, offering a Zionist promise of being led to the land of the Star of David.

The song “Eli, Eli,” for which Jones was particularly praised, requires special attention. Composed for a Yiddish operetta in 1896, in the wake of horrific pogroms in czarist Russia, it speaks of the suffering and despair Jews have experience over the ages yet affirms their faith and devotion to the God of Israel. The song became particularly popular in the 1920s, after the murderous devastation Jews experienced during the First World War and the Russian Civil War. Jack Gottlieb, author of Funny, It Doesn’t Sound Jewish: How Yiddish Songs and Synagogue Melodies Influenced Tin Pan Alley, Broadway, and Hollywood (2004), comments that the song was considered “sacred stuff” and would never be tampered with, always sung in its original Yiddish. Though it was originally written for a female character it was often sung by male performers, notably Yiddish mega star Boris Thomashefsky. It was further popularized by celebrity cantor Yosele Rosenblatt, who in 1927 sang his revised version in the film The Jazz Singer, the first motion picture with sound music. The film starred Al Jolson in the role of a cantor’s son who makes it big on the American stage singing in blackface by virtue of infusing his songs with the soulfulness of cantorial music.

Jeffrey Melnick writes in his A Right to Sing the Blues: African Americans, Jews, and American Popular Song (1999) that “Eli, Eli” became popular with African American singers who strongly identified with it, feeling that it reflected their own painful racial history. Several well-known Black entertainers sang the song, including jazz legend Willie “The Lion” Smith, who felt a special kinship with Jews.

In fact, Smith’s early history shows some similarity with LaRue’s. Both men grew up in Newark. Smith, who believed his birth father was Jewish, was welcomed to sit in on Hebrew lessons as a child by a Jewish family for whom his mother did the laundry. When he turned 13, Smith celebrated his bar mitzvah, and his Yiddish was good enough for him to be able to correct the pronunciation of a gentile singer who in 1925 sang “Eli, Eli” with the Duke Ellington Band. Later in life Smith fully converted to Judaism and served as cantor for a Black Jewish congregation in Harlem.

The inimitable Ethel Waters, the first African American to star on Broadway, reminisced in her memoir about singing “Eli, Eli” in the 1920s, acknowledging that the song moved her deeply, for “it tells the tragic history of the Jews … so familiar to my people.” She added, “Jewish people crowded the theater to hear it: ‘The schwartze sings Eili, Eili.”

Why were Jews so riveted by the Black performance of the song? Was it the frisson of incongruity? The crossing racial and ethnic boundaries? Was it the thrill of acceptance, of hearing their music, language, and culture replicated and validated by gentile America? Perhaps it was a kick to see yourself performed by others? Or was it perhaps a way of achieving whiteness via the agency of Blackness, as some critics of The Jazz Singer have suggested?

The case of LaRue Jones differs, of course, from Smith’s and Waters’. He performed for Jews in Jewish venues, singing an entirely Jewish repertoire, and carefully authenticating himself wearing cantorial garb and using a Tevye as his stage name. Unfortunately, we know so little. Did he suffer from racism within the Jewish world he inhabited? Was he just a curiosity or was his singing taken seriously? What did he feel when not on stage, alone at home or in a hotel room? Did he feel “Jewish” in a highly racialized world? Did he dream of a greater showbiz career? Was he an imitator of other cantors, or did he try to offer his own original interpretation of the material he sang? A brief announcement on Dec. 14, 1930, in Haynt, a major Warsaw Yiddish newspaper suggests an ambition to expand his horizon. It announced that on Saturday evening, at 10:15 p.m., the Black Cantor Tuvia Ha’Cohen, will perform on Warsaw radio two cantorial pieces (“Et Zemach David” and “Eda Tsdakot”) as well as several “Negro songs” and American jazz hits.

Jones died in 1954, buried in an unmarked grave. Henry Sapoznik, anxious to secure a lasting memorial, raised funds for a proper monument. The unveiling of a commemorative headstone took place on Aug. 29, 2021, at the Rosehill Cemetery in Linden, New Jersey. It was attended by 20 people who came specially to pay their respects to a long-forgotten performer. Though not Jewish, the ceremony and the headstone recognized the way that a sense of Jewish identity had shaped the singer’s life and his work, even if the songs he sang inevitably meant something different to a Black man from Newark than they did to his Jewish American audiences.

Edna Nahshon, a professor of Theater and Drama at the Jewish Theological Seminary, is the author of New York’s Yiddish Theater: From the Bowery to Broadway (Columbia University Press, 2016) and Wrestling with Shylock: Jewish Responses to The Merchant of Venice (Cambridge University Press, 2017).