The Art of the Teardown

An interview with the artists whose effort to highlight the fate of kidnapped Israeli children ended up underscoring the moral and social rot of our cities and universities

Richard Baker/In Pictures via Getty Images

Richard Baker/In Pictures via Getty Images

Richard Baker/In Pictures via Getty Images

Israeli street artist Nitzan Mintz, 32, and her partner, Dede Bandaid, 36, had just arrived in New York to study at an art residency, when Hamas terrorists crashed through the Gaza border fence and unleashed their barbaric rampage of murder, rape, arson, and torture on Jewish communities inside Israel. The shocked couple withdrew from their art program before it had even started, and tried to think of what they could do to help the desperate situation at home. Recalling the “Missing Children” pictures on milk cartons that Bandaid said had become “iconic” around the world via American films, they focused their attention on the hostages, whose number, at first thought to be around 130, has now risen to 239.

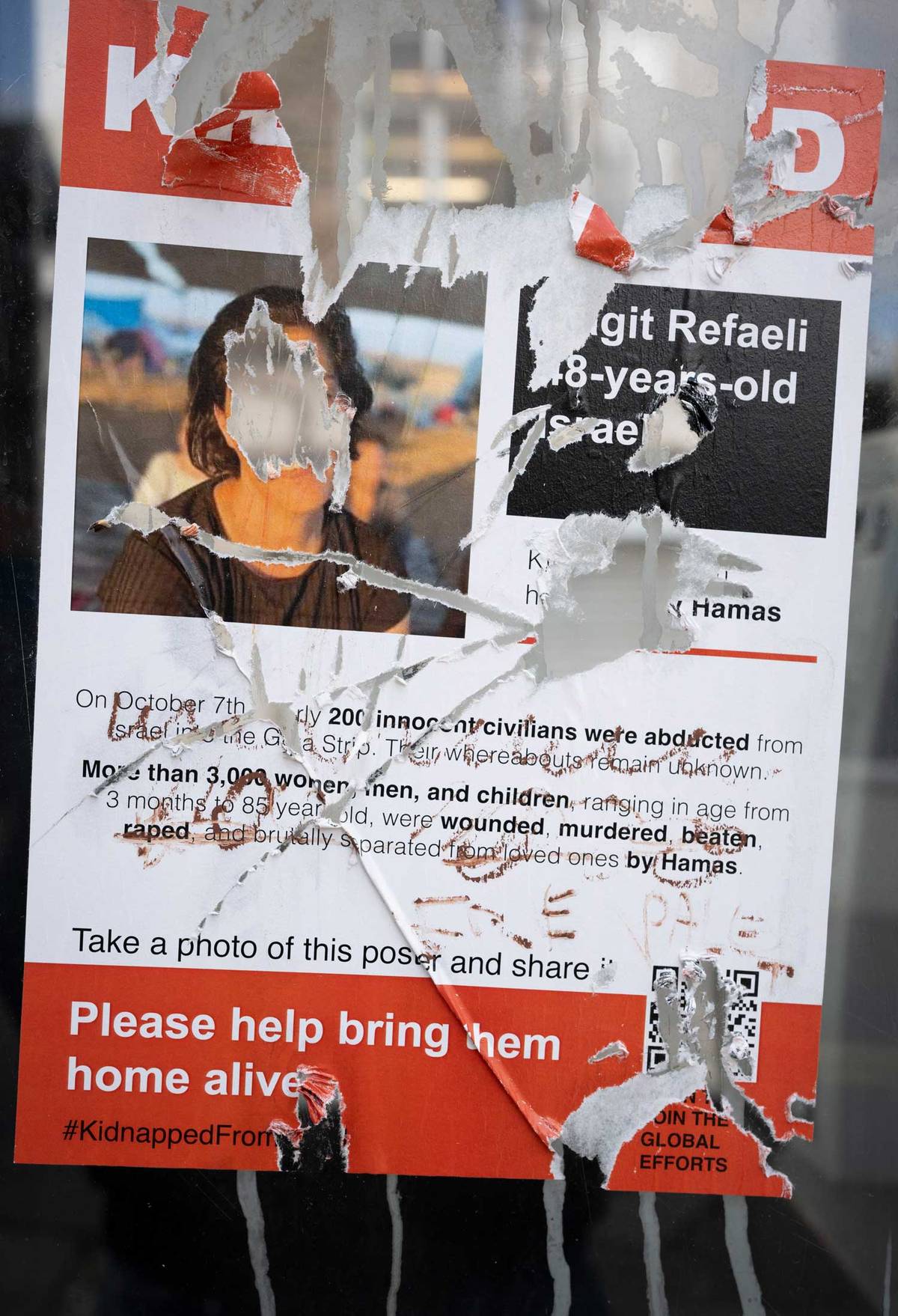

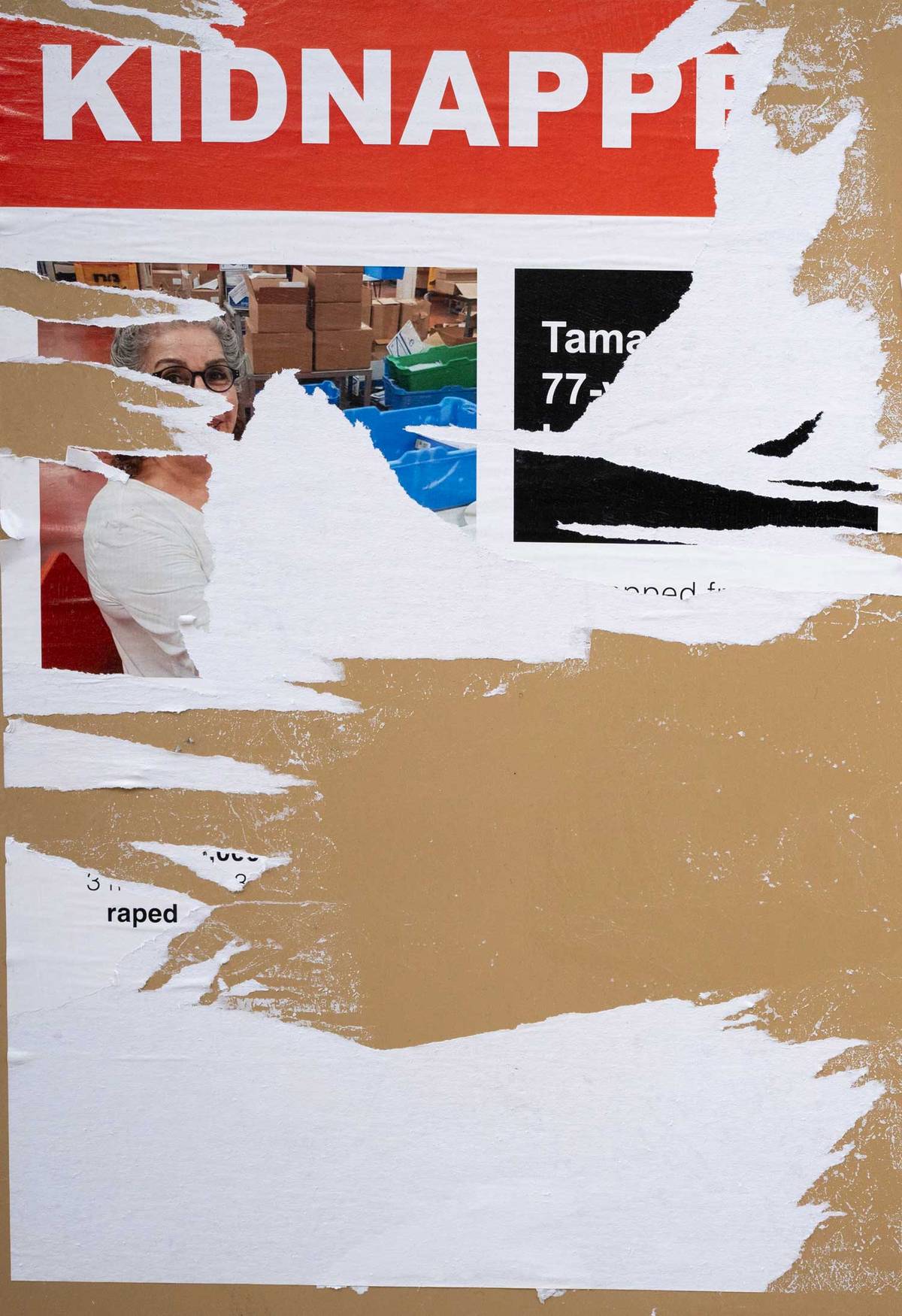

With the help of Tal Huber, an accomplished graphic designer in Israel who is the founder and creative director of the branding house Giraffe, they came up with the now-famous posters featuring a thick red border on top with “Kidnapped” in white capital letters, and below that, photos of the babies, toddlers, adults, and elderly men and women who were dragged from their homes in the early morning of Oct. 7 into Gaza’s labyrinth of tunnels and underground hideouts by an army of murderous terrorists. On the posters is a brief description of the attack and on the bottom, the message: “Please bring them home alive.”

The couple, both of whom are from Tel Aviv, have been together for a decade. Bandaid says they started to make “street art” in their teens, separately “painting walls or sketching random vandalist art” with spray cans after school. After they served in the army, they attended art schools, he at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem, she at the Minshar School of Art in Tel Aviv, “all the while creating in the streets.” After they met, they shared studio space and worked together, traveling and creating, with their work being shown in galleries and museums around the world.

Bandaid is a painter, whose work often features images of Band-Aids. He has written: “I was seeking a way to express and heal my wounds. The band aid then became a symbol for all kinds of difficulties—personal and social—seeking fix.” Nitzan is a poet. She paints her poems in public, sometimes as stand-alone graffiti, sometimes besides her partner’s representations of Band-Aids.

Richard Baker/In Pictures via Getty Images

On Oct. 9, Bandaid and Nitzan put up their first posters in New York City. They began in Central Park and walked down to lower Manhattan. “At the beginning people didn’t want anything to do with us,” Bandaid told me. To increase their reach, they uploaded the posters to Dropbox and announced their availability through social media. They opened Facebook and Instagram accounts called “KidnappedfromIsrael.” They made a website with the same name. Anyone could download the posters, print them out, and put them up in public spaces.

When I first spoke with Bandaid on Oct. 12, people were printing out their posters and hanging them in France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and sending back photos to the group’s Instagram and Facebook pages. Within days, the couple needed help to manage the internet traffic. By Nov. 2, “it is everywhere, around the world,” Bandaid told me, with the locations of the most downloads being Germany, London, Paris, New York, and Argentina. Interestingly, the posters were also being downloaded in unexpected places like Qatar, the Emirates, Morocco, and Egypt. “Maybe they have another idea for our files,” Bandaid said, “but it’s being downloaded there.” The posters have now been translated into 30 languages, and the system is “updating all the time” as Mintz and Bandaid collect more hostage names and information, in coordination with the families. In addition to the “thousands” of people hanging posters, others approached Bandaid and Nitzan with ideas like digital TV trucks, billboards in sports arenas and in Times Square, even what he calls “guerrilla projections,” including on the walls of the United Nations.

Bandaid and Mintz knew that their project could be controversial. They warned on their website: “Be safe—don’t provoke or instigate any conflicts with people or officials. Act quickly and stay alert.”

That advice would turn out to have been prescient in ways that the artists themselves didn’t imagine. Immediately, people began pulling down the pictures of hostages from walls, subways, bus stops, telephone poles, angrily, purposefully, often tearing the paper posters right across the faces of kidnapped children. They carried them away in self-righteous handfuls or stuffed them in trashcans. In addition to helping raise awareness of the fate of the hostages, Bandaid and Nitzan’s poster campaign was now also highlighting the startling prevalence of raw antisemitism within the flagships of Western enlightenment—in large cities and on university campuses.

“The first torn-down posters we saw I think was a video coming from London,” Bandaid recalls, “two Muslim women tearing down posters.” When observers criticized the women, they responded, “We are doing this for Palestine.”

It was not immediately clear, to most normal observers, why concern for the fate of hundreds of innocent people grabbed from their homes and held as hostages in inhumane circumstances in blatant violation of international law should elicit any reaction but grief. Yet the teardowns increased, and soon became the story. Some of the vandals filmed themselves tearing down posters and uploaded footage of their actions to social media, as proofs of their virtue and in the hopes of inspiring others. Others yelled at strangers filming them. The destruction went on in Boston, London, Miami, New York, Melbourne, Philadelphia, Ann Arbor, Los Angeles, and Paris. Hitler mustaches were drawn on the faces of two 3-year-old twin girls. Vandals scrawled “Actors” and “Lies” on others.

“There is no possible justification for such heartlessness,” wrote Jeff Jacoby in The Boston Globe. “The whole purpose of the fliers is to heighten awareness of the Israeli (and other) civilians kidnapped by the Hamas terror squads—to put names and faces to the hostages, all with one goal: to bring them back home. How can a project so heartfelt and humane trigger such a poisonous response?”

The vandals had their own ideas. These ideas were often confused, illogical, sometimes wrong on the facts, but were all expressed with intense, shaking emotion. They seemed rooted in a deep identification with the hapless, helpless, and voiceless, which in their minds justified not just tearing down posters of real human beings in terrible circumstances but also the kidnappings themselves.

The hundreds of videos of people tearing down posters have become as widespread as the posters themselves. Some of the perpetrators are enraged and inarticulate; some are furtive and defensive; some are proud of their actions; some are creepily smug. All of them seem to be operating on a similar odd frequency, in which their actions signal their belonging to a group with impenetrable beliefs that are not open to discussion or questioning, like a cult. In the U.S., at least, nearly all were current or aspiring members of the professional classes.

A worker at the University of Pennsylvania’s Carey Law School, videotaped while tearing down posters on campus, was asked why he was destroying posters of innocent victims. He shouted, “Get the fuck out of my face,” and when informed the photos were of innocent victims, said “There were people killed in the hospital bombing,” referencing the deaths at the Al Ahli Arab Hospital in Gaza that was later attributed to an Islamic Jihad rocket gone astray. When asked why she was tearing down the posters, a woman in New York said, “Because they are fake.” Francesca Martinez-Greenberg, who according to her LinkedIn profile is a graphic designer at the Center for National Security at Fordham Law School, said, “This is part of a concentrated propaganda effort to rile up support for the genocide of Palestinian people.” A man identified as Joe Friedman tore down posters at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond, explaining, “what about the Palestinian children?” and then made fun of an observer’s Israeli accent, calling it “fake.” Friedman, who comes from tony Silver Spring, Maryland, was previously arrested while disrupting a pro-life event on campus at VCU.

The barbarity of the Hamas attack on innocents was thus impossible for those who hate Jews to process, so they didn’t. Rather, they attempted to deny the evidence by throwing away photos of the real-life Jewish victims, in a vain yet chilling attempt to resolve their own logical impasse.

The teardown artists elicited their own social media-driven response, which in some cases included real-world consequences. Observers hunted down the rippers on social media and outed them. NYU law student Ryna Workman, who was filmed destroying posters with a companion, who coyly said she was “very proud” of their actions, saw her job offer from a top law firm rescinded after video of her acts was posted online. Laurel Squadron, who works part time as a babysitter for ArtistBabysitting, a boutique child care agency serving families in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and New Jersey, was filmed tearing down posters of children and screaming, “you support genocide you asshole,” at observers. The agency later denounced her actions and pulled her profile off the job site. An endodontist tearing down posters in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, was outed by StopAntisemitism and fired from her job. New York County public defender Victoria Ruiz was filmed tearing down posters of kidnapped Israeli children, and she later resigned from her position.

In a viral incident reported by the New York Post, construction workers jumped out of their truck to stop a man in Queens from tearing down the posters. “This is a free country,” said one of the men, named Paulie. “You can wave your Palestine flag and say death to the Jews and America whenever you want, but we can put up f–king signs.” He pointed out the man was breaking the law by littering.

Although Bandaid had anticipated some trouble, he admitted the poster destruction “was not so nice to see.” He was also surprised to observe the vandalism on the Upper East and Upper West sides of Manhattan. “You would think there are so many Jews there, that maybe it will be more protected, but you can feel the hate.”

And hate it was—sometimes calm, cool, self-confident, and entitled, and sometimes hysterical. A 24-year-old Israeli student enrolled in general studies at Columbia University in New York City was putting up posters on campus when he was assaulted by a masked female Jewish student named Maxwell Friedman, who was later arrested and charged with assault after breaking her victim’s finger with a stick. A vandal tearing down posters while walking her dog in Miami admitted Hamas was a “terrorist organization” but, shaking with emotion, she said she was ripping down the pictures of hostages to “protect Palestinian civilians” who “over decades have been oppressed; they’re in apartheid because of what Israel is doing.”

RICHARD BAKER/IN PICTURES VIA GETTY IMAGES

One observer on Instagram understood right away what was happening. A young Israeli woman from South Africa explained the rippers were compelled to tear down the photos of innocents kidnapped because “it doesn’t fit the propaganda they’ve been feeding the world,” which denies the humanity of Jews and Israelis while painting them as monsters who oppress innocent Palestinians. “Every video we post, every death and missing person we announce, it’s all ‘fake’ and we’re ‘making it up,’ never mind the fact that the most graphic videos we have of the crimes committed on our innocent Israeli angels are taken by their own leaders.”

The barbarity of the Hamas attack on innocents was thus impossible for those who hate Jews to process, so they didn’t. Rather, they attempted to deny the evidence by throwing away photos of the real-life Jewish victims, in a vain yet chilling attempt to resolve their own logical impasse. “Precisely because the massacre and abductions had been so unspeakably horrific,” Jeff Jacoby wrote, “it was necessary to reinforce the narrative of Jewish villainy.”

Mintz and Bandaid are hurt by the blood-curdling reactions, but they remain undeterred. “You know, we are only going to put the posters up again, and all the thousands of people who are with us, they just print more and put them back up,” says Bandaid. “We put innocent civilians on these posters because we know they can’t speak for themselves right now. We have to keep their names up there and keep spreading awareness until they gain their freedom.”

Bandaid and Nitzan’s posters continue to be downloaded. (There are fewer reported teardowns in the Far East.) Posters have been displayed on 240 chairs surrounding an empty Shabbat table that has been constructed and displayed around the world: in New York, Geneva, Boston, Berlin, Rome, Frankfurt, Washington, D.C., Johannesburg, London, Copenhagen, Tel Aviv, Melbourne, Tbilisi, Chicago, Vienna, LA, and Lisbon, to name a few.

In the fourth week of the war, analytics show that kidnappedfromIsrael.com has been visited an average of 30,000 times per day.

Nevertheless, Bandaid has to admit the rage is terrifying. “They tear down photos of babies and elderly people!” the artist told me. “It’s just pure evil. It’s not human. It’s really crazy. It’s really upsetting. We see antisemitism rising everywhere. It’s not a nice feeling to have when you’re abroad, and we feel less and less safe. It’s scary and it’s depressing to see the world act like that. But we will just go out and put up more.”

Emily Benedek has written for Rolling Stone, The New York Times, Newsweek, The Washington Post, and Mosaic, among other publications. She is the author of five books.