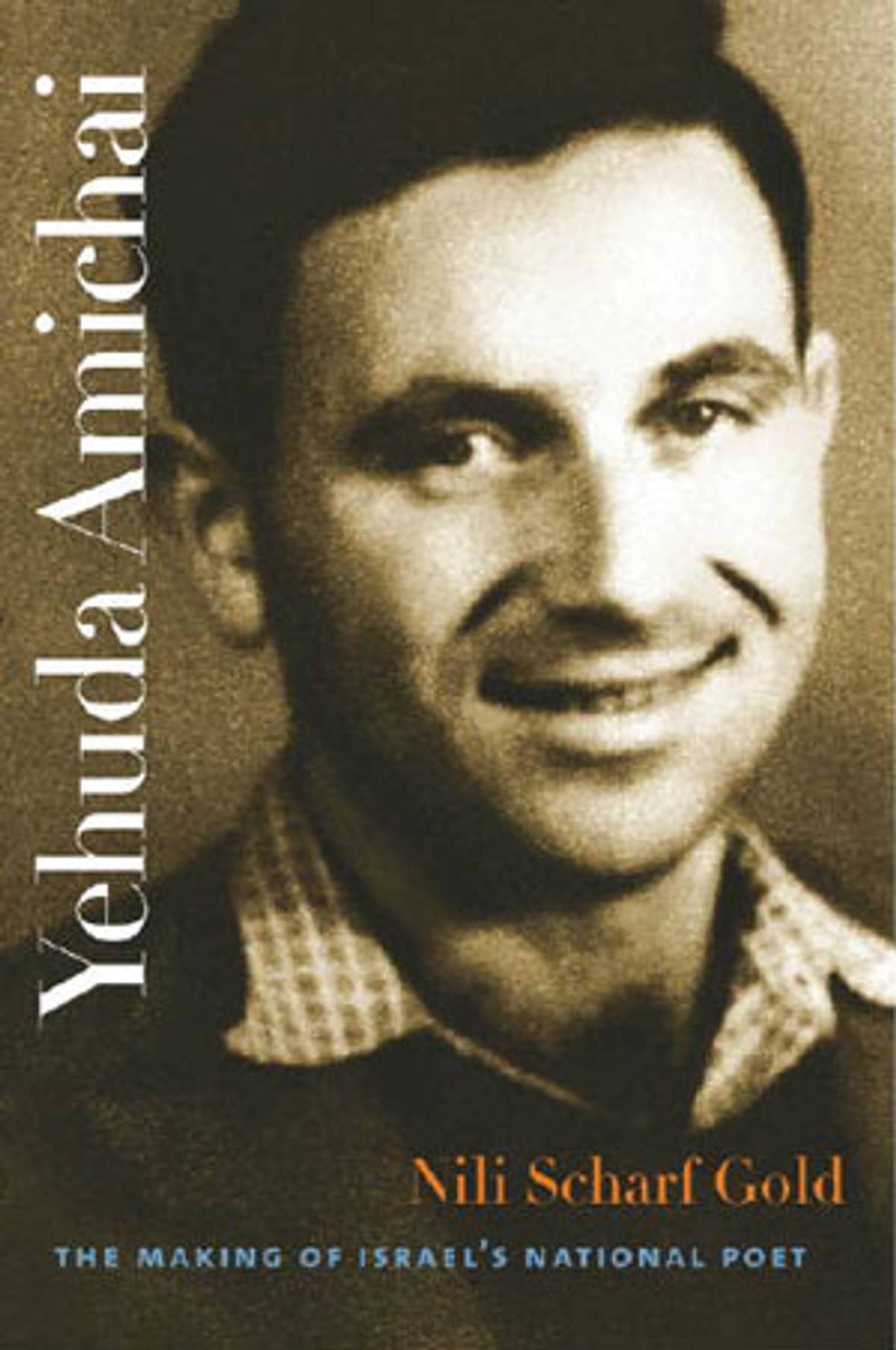

When Hollywood scouts look for new books to turn into screenplays, they probably don’t spend much time with the catalog of Brandeis University Press. But underneath the scholarly surface of Yehuda Amichai: The Making of Israel’s National Poet, by Nili Scharf Gold, lies a blockbuster just waiting for the right director to come along. Imagine a cross between Possession and Exodus—a story of love and literary detective work set against the backdrop of Israel’s War of Independence, complete with hidden love letters, tragic partings, and heroic battles. That the hero of the story is Yehuda Amichai, Israel’s greatest poet and one of the major writers of the 20th century, is just the icing on the cake.

The story opens in 1997, when Gold, a professor of modern Hebrew literature at the University of Pennsylvania, accompanies Amichai to a lecture in New York. “We sat in a back row at the end of a crowded hall and waited for the speaker to begin,” she writes in her introduction, “when suddenly he touched my arm and said, almost in a whisper, ‘Do you see, three rows in front of us, near the aisle, a woman sits? Her name is Ruth Z. Do you remember the poem about the one who ‘ran away to America’? I wrote it about her.”

That poem is “‘History’s Wings Beating, They Used to Say’” (as translated by Benjamin and Barbara Harshav in Yehuda Amichai: A Life of Poetry, 1948–1994):

Those were days of great love and great destiny,

The foreign power imposed a curfew on the city and closed

Us for a sweet coupling in the room,

Guarded by well-armed soldiers.

For five shillings I changed the name of my forefathers

Of the Diaspora into a proud Hebrew name matching hers.

That bitch ran off to America, got married to

A dealer in spices, cinnamon, cardamom,

And left me behind with my new name and the war.

Amichai died in 2000, but two years later, Gold happened to be introduced to Ruth Z., the woman who broke the poet’s heart. In subsequent meetings, Gold writes, Ruth “unveiled a story that had been hidden for half a century”—the love story Amichai alluded to in his bitter poem, which is also, Gold argues, the secret history of his origins as a poet. What’s more, Ruth showed Gold the kind of treasure that every scholar dreams about: a cache of some 100 letters written by the poet in 1947–8, in the most dramatic months of Israel’s history, which had never been seen by another soul. No wonder that “when Ruth opened the box, my heart skipped a beat”: if it really were a movie, this is the moment when the present would dissolve and the epic past would surge back to life.

In 1947, Yehuda Pfeuffer, as he was still known, fell in love with Ruth Z. when they were fellow students at a teacher’s training college in Jerusalem. It was the period when Jews, Arabs, and British occupiers were fighting an undeclared civil war, and the future of Jewish Palestine was still an open question. In this context, for Pfeuffer to “change the name of his forefathers” to the “proud” Amichai—“my nation lives”—was a defiant act of Zionist patriotism. According to Ruth, it was also a kind of betrothal; the couple chose the name together, “looking for a Hebrew name that would melodically complement both ‘Yehuda’ and ‘Ruth.’”

But the name would not be shared, after all. At the end of August 1947, Ruth left Palestine for America, where she fell in love with another man and got married. Before the final rupture, however, the lovers corresponded for eight months; and if the parting was a torment for Amichai the man, it was also a kind of boon to Amichai the poet. It gave him a devoted audience for his thoughts about the Hebrew language, Israeli nationhood, and the nature of poetry—the very themes that would shape his writing for the rest of his life.

The letters, which Gold extensively paraphrases but does not quote at length, also reveal Amichai’s genuine heroism at a moment of national danger. By day, he was a beloved elementary-school teacher in Haifa; by night, he was a soldier, patrolling the divided city. In November 1947, he was on board a bus that was sprayed with gunfire; the man in the seat in front of him was killed. (The passengers believed that the gunmen were British soldiers, taking revenge for attacks by the Haganah.) In the following months, the initially apolitical poet was prompted by such incidents to identify more and more with the national cause. When the UN voted to create a Jewish state, he wrote Ruth what Gold describes as “an exuberant and palpable depiction of the collective intoxication on the streets of Haifa.”

Yet as Gold emphasizes, Amichai’s Zionism was tempered, from the very beginning, with the mistrust of heroism and war that is so distinctive in his poetry. Already in the letters of 1947–8, it is possible to recognize the poet of “I Want to Die in My Own Bed,” Amichai’s famous hymn to the civilian virtues:

Samson, his strength in his long black hair,

My hair they sheared off when they made me a hero

Perforce, and taught me to charge ahead.

I want to die in my own bed.

I saw you could live and furnish with grace

Even a lion’s maw, if you’ve got no other place.

I don’t even mind to die alone, to be dead,

But I want to die in my own bed.

If the years of his affair with Ruth were so important to him, however, why did Amichai never write openly about her? Why did he even tell interviewers that it was his experience of combat in the Negev in 1948 that first made him want to be a poet, when it is clear from the Ruth correspondence that he was writing poetry long before the War of Independence?

Here the biographical elements of Gold’s book merge into her intriguing but debatable critical thesis. Amichai’s main technique as a writer, Gold argues, was “camouflage”: the deliberate concealing of autobiographical traumas under abstract poetic language. “Amichai’s relationship with Ruth Z.,” she writes,” “was only one of a number of significant facets of his life that he chose camouflage in his verse.” And the most important experience Amichai chose to “camouflage,” Gold argues at length in the book’s first section, was his childhood in Germany.

It is no secret, of course, that from his birth in 1924 until his family fled Germany in 1936, Amichai was known as Ludwig Pfeuffer, or that German was his native language. Through close readings of his poems and drafts, however, Gold shows that German, and the landscape and people of Wurzburg, played a more significant role in his Hebrew verse than he usually admitted. Indeed, Gold even found German drafts of some Hebrew poems, as well as injunctions or reminders the poet addressed to himself in his first language. Above all, Amichai was haunted by the unbearably tragic story of “Little Ruth” Hanover, his best friend from childhood, who lost a leg in an accident and was later killed in the Holocaust. Not until very late in his life did Amichai write openly about her in verse, in the poem “Little Ruth”:

And what happened to the unused years of your life?

Are they still packed away in pretty bundles,

Were they added to my life? Did you turn me

Into your bank of love like the banks in Switzerland

Where assets are preserved even after their owners are dead?

For Gold, finding German traces in Amichai’s Hebrew poetry has profound political implications. It proves that Israeli culture cannot be as completely severed from its Diasporic roots as the first generation of Israelis hoped. But in making this point, and in analyzing the dramatic Ruth Z. material, Gold seems to embrace a rather simplistic notion of the way poets turn their lives into art. She often writes accusatorily, as though Amichai were somehow being dishonest when he chose to write about some experiences rather than others. “While Amichai suppressed them in his corpus, remnants of these potent landmarks survive,” she says, as though poetry were a crime scene or archeological dig.

Poems, however, are not “really” about experiences in the poet’s life; they are about the experience the poet creates in the words themselves. A freer and more generous understanding of how poets work would have made “Yehuda Amichai” a more reliable guide to its subject’s achievement. Still, in biographical if not in critical terms, Gold’s book is revelatory and will certainly change the way we read and think about “Israel’s national poet.”

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.