The Fable of Fania

Salsa U.S.A. meets the Marvelous Jew and spawns ‘Hommy’

Original image: Fania Records

Original image: Fania Records

Original image: Fania Records

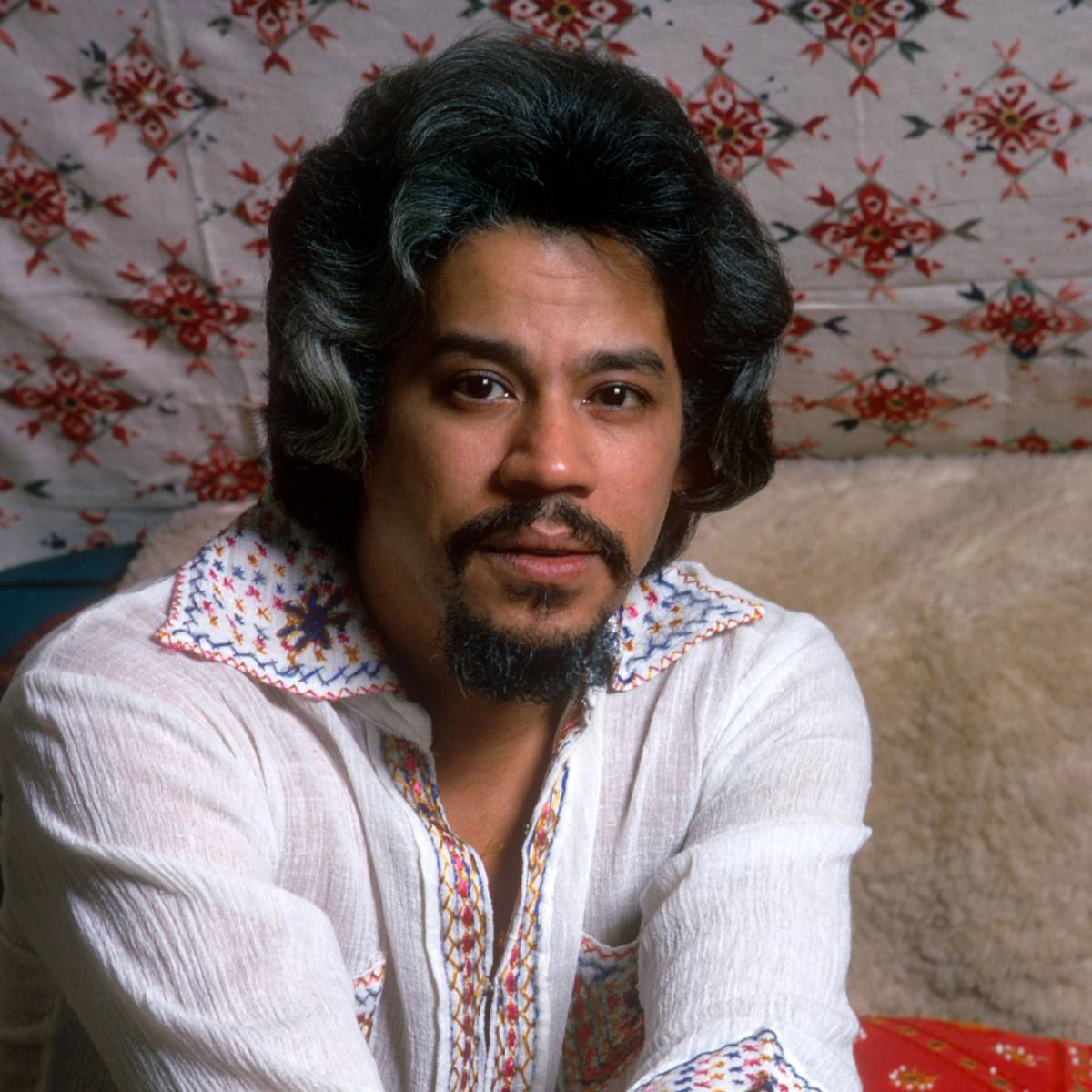

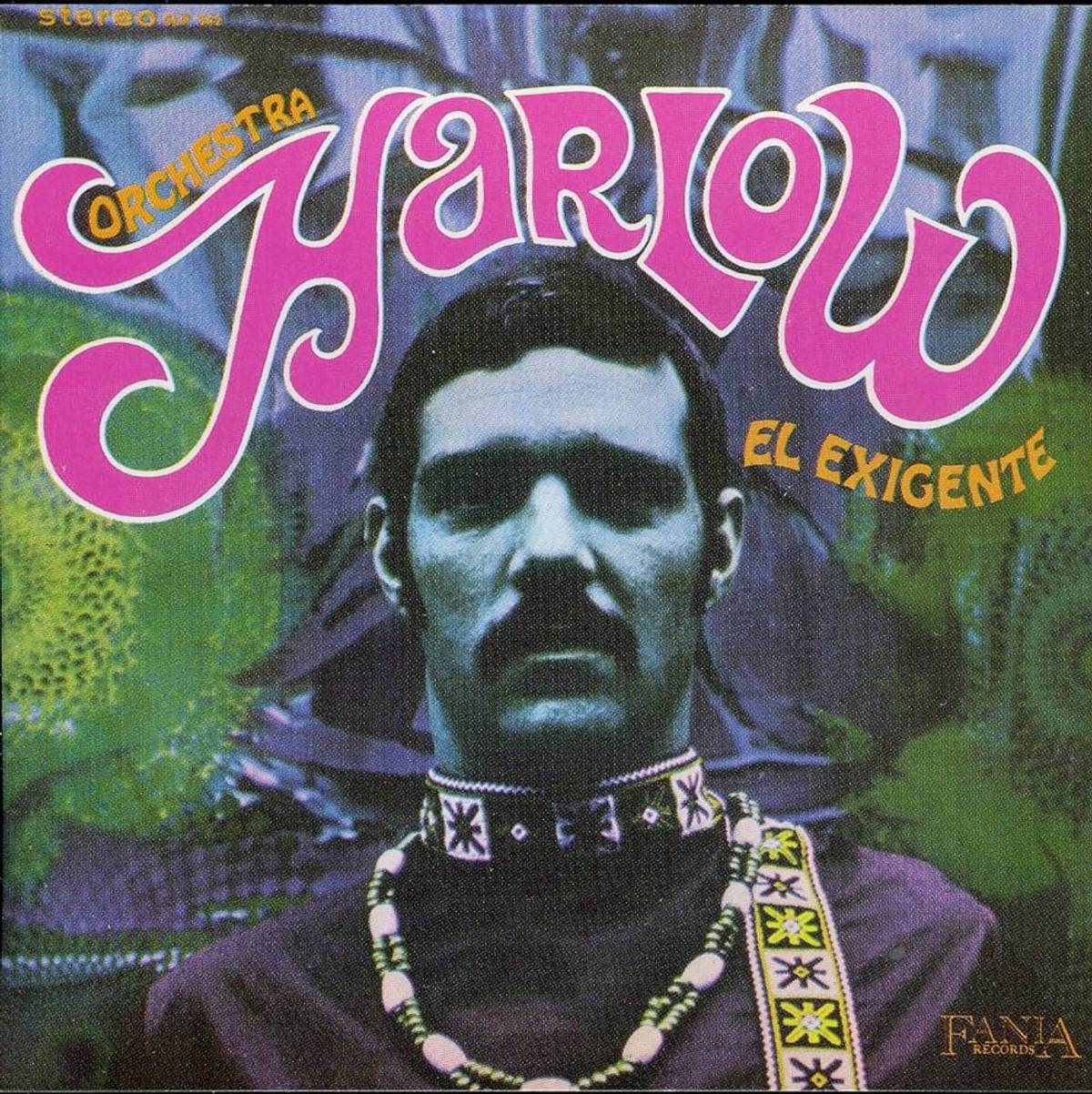

Eighty-five years ago this month, a Jewish opera singer named Rose Sherman and her husband Nathan Kahn—the bandleader at the Latin Quarter nightclub who went by the name Buddy Harlow—had a son. Born Lawrence Ira Kahn, Larry Harlow went on to become a pianist, producer and impresario of Latin music known affectionately in salsa music circles as El Judio Maravilloso (The Marvelous Jew).

Harlow left behind a legacy that included not only his own incredible recordings and influence, but his work as a producer of over 106 albums—including four for his brother Andy Harlow and Andy’s La Lotería, the legendary salsa music label Fania Records’ biggest-selling 45 release. Inspired by the Who’s Tommy, Larry Harlow took salsa music all the way to Carnegie Hall, as he staged the salsa opera Hommy, and was instrumental in Celia Cruz‘s exciting comeback, casting her as “The Acid Queen.”

A key part of Harlow’s success was becoming a primary piano player for the Fania All-Stars, the legendary Latin supergroup born from the record label that gave birth to the sound, and the musical movement that proved to be the most inspiring Latin music sensation of all time: Fania Records. The label of which Harlow was such an integral part produced great music, live music events, and films, and became home to an unmatched output of creativity married to a unique approach to Latin music that is still considered the genre’s high-water mark.

It’s unlikely that Harlow would’ve ever found a home in Latin music if not for the open-minded approach Fania Records brought to the Latin music scene. The occasion of his birthday this month is as good a time as any to tell the story of Fania, which birthed one of the most incredible moments in modern pop music history and created a fertile playground for Harlow and so many others to do what had never been done in Latin music—create a culture which, to this day, has never been equaled.

Born at the height of the turbulent and soulful 1970s, Fania Records was the Latin Motown—the ultimate exploration of bilingual, bicultural Latino pride, featuring artists like Celia Cruz, Hector Lavoe, and Ruben Blades who came to exemplify the Fania sound. Its influence would go on to color every Latin rhythm and beat heard in the years since.

Where in California, the Latino neighborhoods (mainly Mexican American) were mostly separated, limiting a lot of cultural interactions, New York City was its own place. The Latin musical culture of Manhattan was grounded in old school Cuban music, a nightclub staple of the 1940s and 1950s brought back to brass and conga-driven life by the Puerto Rican and Dominican communities in NYC. The city’s melting pot was no joke—it’s where cultures are thrown together geographically, and where, even if they’re separated by a couple of blocks, the culture still literally crashes into itself and rides the trains together. Latinos in New York City had to reckon with the idea of America and its vast influences in a much different way than anywhere else in the world.

Lee Marshall

The New York City version of Latin soul did not want to be “separate but equal.” It wanted to swallow up the culture—and the counterculture too. Everything was grist for the mill, from the Black Panther party, the sexual revolution, 1970s pulpy Marvel comic books, The Godfather films, Blaxploitation movies—all of this would be blended into the amazing output of music that Fania would put out. While Larry Harlow reinterpreted the Who’s Tommy as Hommy, and brought salsa music to Carnegie Hall, Celia Cruz sang about Afro Cuban deities, preserved in worship since the days of the slave trade and on the same album sang the praises of Isadora Duncan, the revolutionary modern dancer.

Izzy Sanabria’s vibrant album covers for Fania surpassed even the wildest rock ‘n’ roll album art: Celia in a dashiki photographed at the home of an African couple in Greenwich Village, the Fania players drawn as superheroes stepping out of a splashy comic book page, and Ray Barretto busting his shirt open to reveal a Superman costume underneath, a conga Clark Kent on his album Indestructible. These covers boldly said, “we are American culture, and we are also something else.”

Fania Records was a wild thing that could’ve only come out of New York City. Jewish New Yorkers, like Larry Harlow and Andy Harlow, along with Italian Americans, like Jerry Masucci, joined with Dominican bandleader and label co-founder Johnny Pacheco, and the largely Puerto Rican cast of musicians who made up Fania’s legendary players, to create the most indelible Latin music ever made. When Marc Anthony played Héctor Lavoe opposite J.Lo in El Cantante, that’s the story of Fania Records. Celia Cruz, the only woman to have a one woman show at the Smithsonian—that’s the story of Fania Records.

“Salsa”—one word to describe all these different kinds of old Cuban styles that Fania recorded—was a word created by Fania to describe the heart of its sound. Fania Records made the film Our Latin Thing, directed by Leon Gast (who’d go on to win an Oscar for When We Were Kings years later) and rented out movie theaters to show it, coordinating screenings with showcase concerts in the area featuring the Fania All-Stars (a groundbreaking practice and a lesson in effective self-distribution of movies and music).

Fania Records helped us to think of ourselves as still proud of our specific ethnicities, despite being universally Latino. Those Latin advertising agencies that sprung up in the ’60s and ’70s to take some of the general market dollars and apply them to the emerging Latin market loved telling their clients that we could all be reached in one fell swoop. Through the music they released, Fania Records was saying ... um, no, this can get very specific. And that’s what makes it universal.

Fania became the sound of good times and hard times, from freezing winters in too cold New York apartments to sweltering summers where the windows opened to disperse cigar smoke, rum, and sweat as people danced their hearts out.

The boogaloo movement of the ’60s was Latin New York’s answer to the British invasion, fusing rock ‘n’ roll to Latin beats and putting a pop twist on all kinds of Latin music. It’s from Fania’s boogaloo releases that we realize the influence of the 4/4ths beat that comes from Cuba, called the Clave, aka the Bo Diddley beat. Fania Records used that beat, and the NYC boogaloo moment, to launch their label and serve up a mix of camaraderie that allowed artists to co-mingle, co-create, and co-headline each other’s albums to create a unique label with a deep bullpen of talent that supported each other on records and in live performances.

As boogaloo declined in popularity, Johnny Pacheco was ready to lead the way with something new. Pacheco had fronted many bands and put out great records but wanted to control his music and his destiny. “I got tired of getting ripped off by the labels, so I figured I’d make my own label, and rip myself off!” he once joked in an interview. Jerry and Johnny decided to follow their mutual love of Latin music and launch Fania Records, named after a song on their first release, Pacheco’s “Mi Nuevo Tumbao, Cañonazo.”

Pacheco was in love with “son,” a form of traditional Cuban music and he was on a mission to popularize it. Son is the basis of what we call salsa. Traditional salsa is rooted in different styles of Cuban music: the cha-cha, guaguanco, pachanga, guaracha, montuno, charanga ... even a little rare Dominican merengue. In order to market all these different kinds of Latin music, someone at Fania Records coined the all-purpose term “salsa.” Most folks, including the U.S. Patent Office website, give Pacheco credit for coming up with it ... but the very jazzy and fantastic Izzy Sanabria, the promoter and graphic artist who designed many of the most seminal Fania album covers, says he came up with it. At any rate, salsa became the sound and feel of Latin New York City and spread out into the world.

Meanwhile, in Cuba, in 1960, a year after the revolution, Jerry Masucci was making plans to leave, and fast. A former New York City cop who had traveled to the island to work for the U.S. State Department and spread the word about the return of democracy and capitalism to Cuba, Masucci sensed that Fidel Castro had other ideas—and that he’d better head for a land with a little friendlier attitude toward his entrepreneurial leanings. Returning the US, Masucci became an attorney, and met Johnny Pacheco when he acted as Pacheco’s divorce lawyer.

Fania Records

Masucci was tough, streetwise, and business savvy; Pacheco was the creative genius who would guide the sound, vision, feel, music, and style of Fania. Johnny and Jerry became unlikely business partners, distributing records on the independent label (and smaller sub labels) they’d create. They sold records out of the back of their cars and ran their business out of a broom closet. The story of Fania Records is really the story of their friendship—a bond that remained through romances and marriages until their dying days.

As Alex Masucci recounted to Billboard magazine in a 2014 profile about Fania: “I remember being 13 years old and Jerry borrowing the money to start the label and my mother writing the check. That was a lot of money, because my mother was a seamstress who worked in a sweatshop factory and my father was a Hertz truck mechanic. I remember Johnny Pacheco coming for dinner. We were sitting outside and he pulled up in a Mercedes. I had never seen a Mercedes before. Then his wife got out of the car, and she was like from another planet. She was gorgeous.”

Alex also worked at Fania, and it became a family affair as the artists and musicians there grew close and inseparable—“us against the world,” at a pivotal cultural moment. American culture was changing rapidly in the 1960s and every movement had a moment. Feminism. Freedom of sexuality and gender. Race and the struggle to make sense of its legacy in America.

In New York City, a Latino movement—and moment—was coming. Between the 1940s and the mid-’60s, New York City’s Puerto Rican population boomed from 70,000 to nearly 900,000, and their presence—their cultura, needed to be reflected. Inspired by the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords Party, a Puerto Rican street gang became a community-based organization that battled for political power and spoils, specifically in East Harlem. They reached national headlines during their “garbage offensive,” where members led a weeklong neighborhood cleanup and held protests and building occupations, and organized free breakfast programs for children. They helped standardize the current federal children’s nutrition program, while establishing free medical clinics, and created a Puerto Rican cultural center.

Fania

Fania was part of that moment of cultural and political self-assertion. As their recordings began to sell, Pacheco functioned as the musical producer and creative director, and Massuci as the business end, specifically scouting Latin artists who had previously found critical acclaim but were not signed at that time, and negotiating contracts with various musicians and bands to bring them to the label. Pacheco himself headlined the label’s debut release, which combined several Afro-Cuban dance music styles.

In a time of political turmoil and civil rights movements, Fania Records provided a platform for Latin artists to voice their opinions and share their experiences. Their music inspired generations of listeners to embrace their cultural roots with pride. Songs were often about barrio life as an immigrant in the city, which closely linked salsa with the surrounding minority communities. The tracks like “Pueblo Latino’' by Ismael Miranda and “Si Se Puede’' by Willie Colón addressed the plight of the Latin American diaspora and encouraged unity in the face of adversity. Ruben Blades and Willie Colón’s album Siembra dealt with the harsh realities of barrio life, but also brought in Blades’ pan-American sensibilities, crafting a unique pop narrative with incredible nuance.

The label’s visionary approach paved the way for salsa to flourish and find global acclaim.

Johnny Pacheco’s experience as an immigrant and his early exposure to the diverse musical landscape of New York City heavily influenced the direction of Fania Records. He wanted the label to be a haven for Latin artists, a place where they could express themselves without compromise. This commitment to artistic integrity helped build a roster of artists who were not only immensely talented but deeply connected to their cultural roots.

Fania titled songs in English and had cover shoots similar to American rock ’n’ roll records, they cultivated a mainstream image to rival popular English language pop labels and still had a unique sound rooted in Latin culture. While the music of Fania Records enraptured the hearts of millions of record buyers, the dance floors of New York’s legendary clubs was where their salsa truly came alive. The Cheetah (which was featured in Fania film’s Our Latin Thing), the Peppermint Lounge, Les Violins, the Village Gate Nightclub, and La Epoca were just a few of the spots where salsa was exploding. Salsa also took over the Copacabana, the epicenter of Latin music in New York for 70 years.

Salsa’s unique blend of danceability, catchy hooks, sensuality, rhythm, and charisma made it something that transcended age, race, and social status. Whether in the dimly lit clubs of Nueva York or the glamorous ballrooms of Manhattan’s elite, salsa dancers moved in unison, exuding joy and community through dance and a shared love of music. Sharing the stage with disco, salsa dancing made it all the way to Saturday Night Fever. At the dance contest at the end of the film, John Travolta’s Tony Manero character gives away his trophy to the … well, more deserving salsa dancers.

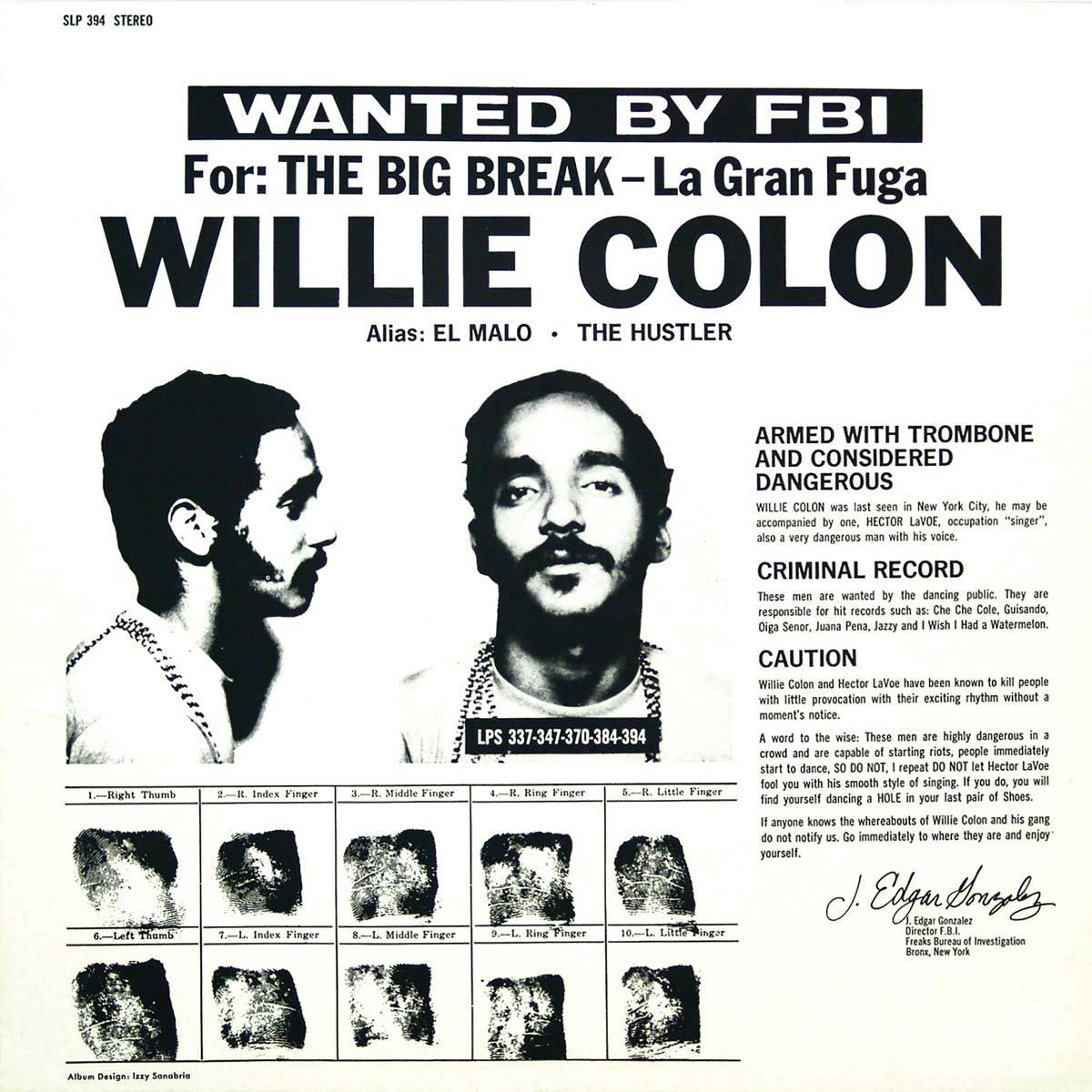

Like Motown at its heyday, which featured stars as diverse as Marvin Gaye and Smokey Robinson or The Supremes and The Temptations, Fania had many artists with unique and vibrant personalities. Willie Colón had a take on American gangsters in the movies right out of The Godfather, and released albums that embraced this image with titles like La Cosa Nuestra (“Our Thing” instead of Cosa Nostra), Wanted by the FBI and El Malo, (The Bad Guy). His “crime pays” image and Rolls Royce almost made him a precursor to gangster rap. He documented daily life in the barrio with the style of the New York gangster films that dominated The Late Show.

Interestingly, the real gangster of Fania was a young man named Joe Bataan, who got his start making much more upbeat, “feel good” music. Bataan was of Filipino and African American descent, but he passed as Latino and fell in love with piano during a stint in reform school. Bataan became a champion of boogaloo music, and broke through with it—but he infused a bit of social consciousness into it. He described it as cha-cha with a backbeat. He told the Guardian, “I was a neighborhood thug and got kicked out of school and sent to reformatory.” One night he found a group of teens rehearsing some music, popped his switchblade and stuck it in the piano, and declared himself their bandleader. Within six months, they were recording their first album for Fania Records. That’s the closest the mob came to Fania.

In the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, the Mafia made big inroads into the music business. Infamous label owner and extortionist Morris Levy was involved in New York’s successful Latin music scene. He even owned the legendary precursors to Fania, the successful and soulful Tico and Alegre record labels. But due to either Masucci’s tough cop past and tough lawyer present, or just to fate, Fania always controlled their own destiny. In fact, Levy was forced to sell his Tico and Alegre record labels to Fania in 1974. It was a victory for justice at a time when the music industry was rampant with malfeasance.

Inspired by the bold directions in pop culture of the ’60s, Fania encouraged experimentation. Ruben Blades, who started out life in the Fania Records mailroom, and later became an actor, political activist, and a political figure, even running for president of Panama, first made his landmark album with Willie Colón, Siembra at Fania. That groundbreaking album where his salsa and Latin music bona fides reside, Siembra was almost the Latin version of Sgt. Pepper’s in terms of adventurous production, yet it was also concerned with tackling large political themes.

Willie Colón made many of his albums with Hector Lavoe, and it’s Lavoe’s song “Mi Gente” that stands as Fania and salsa music’s all time anthem.

Larry Harlow didn’t just bring salsa music to Carnegie Hall with Hommy—his albums for Fania redefined the role of a Latin jazz pianist. He changed the way this music was played, arranged, and produced. As he toiled behind the boards for Pacheco as Johnny arranged things, Harlow even composed a salsa “suite” called La Raza Latina, made in collaboration with the brilliant Ruben Blades, which was a history of the story of Latin music.

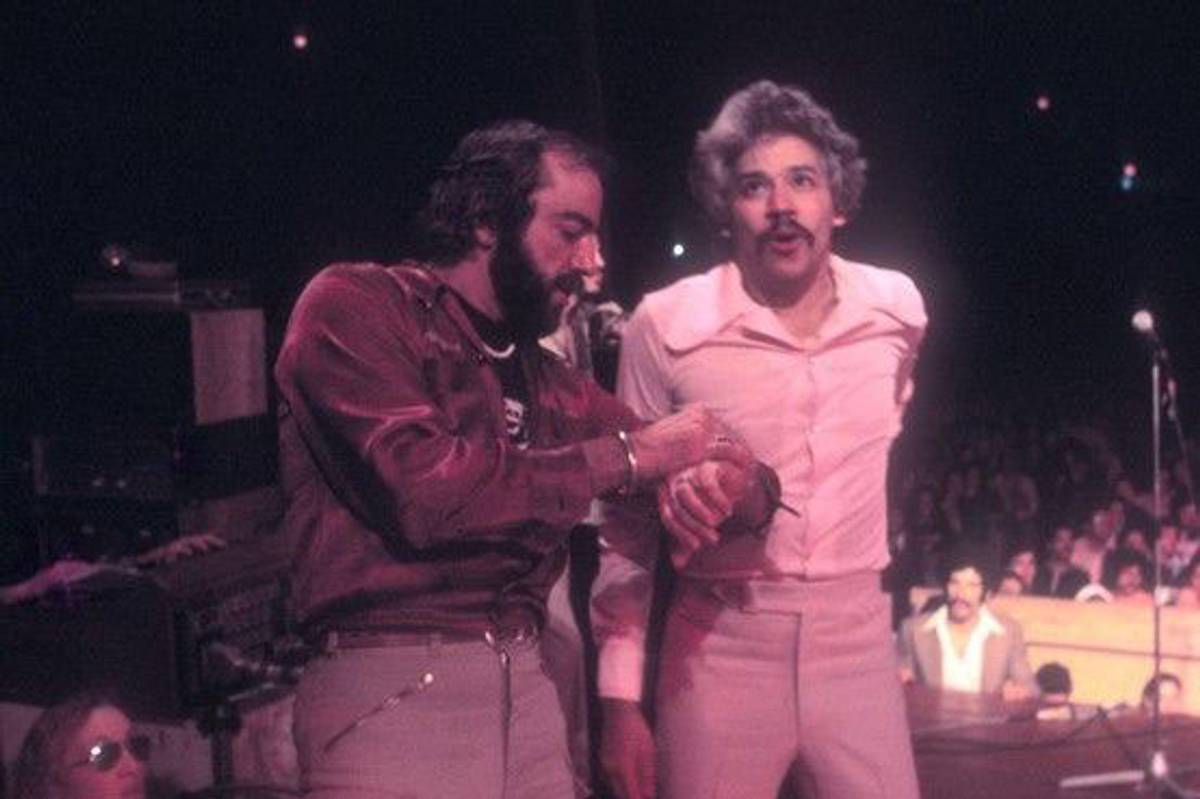

These freewheeling collaborations—where all the talent would reach out and embrace and work with each other—were at the heart of Fania Records’ success and key in the creation of the Fania All-Stars, an ensemble of the label’s most prominent artists who came together to form a live musical juggernaut. Composed of luminaries like Celia Cruz, the “Queen of Salsa”; Willie Colón, the trombone virtuoso; Hector Lavoe, the magnetic voice of salsa; Ray Barretto, the influential conguero; and Rubén Blades, the talented singer-songwriter and actor, and Harlow—with his brilliant piano playing—the Fania All-Stars delivered electrifying performances that transcended language barriers and cultural boundaries.

The Fania All-Stars performances not only became iconic moments in music history but also platforms for celebrating Latin heritage and promoting social unity. Their iconic Our Latin Thing concert at Yankee Stadium in 1973 served as a symbol of empowerment and unity for the Latin community in New York. The event showcased the richness and diversity of Latin music and brought people from various backgrounds together, fostering a sense of cultural pride—and proving salsa music could sell out Yankee Stadium. The concert was booked to coincide with a showing of their documentary film of the same name.

Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images

The All-Stars took this formula all over the world, as the film was screened by Fania concurrently with concerts around the globe. The Fania All-Stars traveled to Zaire, where they co-headlined (with the great James Brown) the legendary concert portion of the George Foreman/Muhammad Ali boxing match “Rumble in the Jungle.”

Not only did these stars gain global recognition and musical success, Fania Records also catapulted artists out of stagnant careers to great success. Celia Cruz, once a Cuban and global sensation, was almost forgotten before her Fania tenure, but when she came to Fania, Johnny Pacheco’s arrangements and production skyrocketed her career and placed her back into the firmament of international stardom, and she ignited the world of Latin music for the remainder of her career—donning dashikis one day and high-heeled platform shoes the next, singing Afro-centric songs about Santeria and African gods one day and an ode to mother of modern dance Isadora Duncan the next—Celia was a Cuban genie sprung from the salsa bottle.

Even Fania promoter and album cover designer Izzy Sanabria became a star, hosting Salsa, sort of a Latin version of Soul Train, on a New York television channel.

Fania Records made an attempt to cross over with the 1976 album Delicate and Jumpy, which was released on a major label and featured a guest slot from rock great Steve Winwood. But by the early ’80s, Fania had stopped recording new music and many of its stars had left the label. Pacheco, now a legendary figure, had moved on, collaborating with David Byrne on his excursions into Latin music.

According to Billboard magazine, when Fania Records quietly ceased production in the early ’80s, it boasted more than 1,000 albums, more than 3,000 compositions under Fania publishing, and approximately 10,000 master tracks.

The stories that surround Fania records continue to be told—who can imagine the day to day intricacies and adventures and romances of this undertaking? We dream about it all even as we listen … These songs need to be sung.

Matti Leshem is the co-founder of New Mandate Films, a film and television production company created to mine the rich depth of Jewish history and literature.

Bill Teck coined the term and created the Latinx brand “generation ñ” and the groundbreaking Spanglish internet content, documentaries, TV shows, books, and magazines that sprang from it. Teck is also the director of the acclaimed Warner Bros. documentary One Day Since Yesterday: Peter Bogdanovich and the Lost American Film.