The Jewish Tolstoy of Berdychiv

The third stop of my literary tour of Eastern Europe brings me to the home of Vasily Grossman, the great bard of WWII.

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

Wikipedia

“Now at night, Vitya, I am seized by terror, from which my heart freezes. Death is waiting for me. I want to call you for help. As a child you would run to me, seeking protection. And now in a moment of weakness I want to hide my head in your lap, so that you, smart and strong, would shield and defend it. I do not possess the strength of character, Viktor, as I am weak. I often think about suicide. …”

The passage above is from Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate, now recognized as one of the great novels of the 20th century. And it was a book the KGB did everything it could to kill.

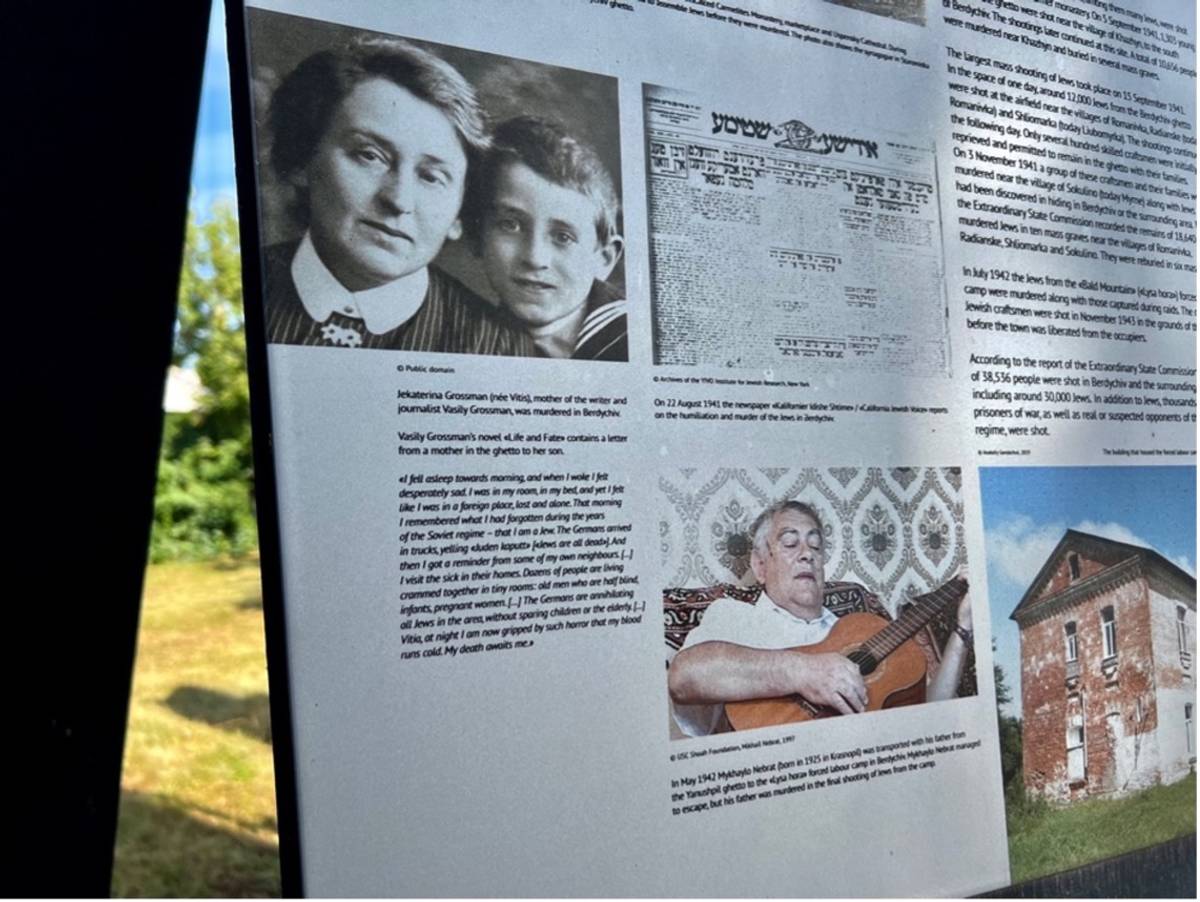

This excerpt is from one of the book’s most moving chapters: the last letter written by the protagonist’s mother to her son. Anna Semyonova is imprisoned in the Berdychiv ghetto. She knows she will not survive and writes her final words to her son Viktor Shtrum (Grossman’s alter-ego). She hands the letter to someone on the other side of the ghetto fence; it will be passed to seven different people before Shtrum reads it in his dacha outside Moscow. And there I was, in a city park by an impressive Holocaust memorial to the 30,000 murdered Jews of Berdychiv, staring at a picture of an adoring, clinging Vasily Grossman, aged around 9 or 10, and his mother, Ekaterina Savelyevna Grossman.

Getting to Berdychiv from Kyiv isn’t easy. After buying a ticket, I made my way to Kyiv’s central bus station, where a rumbling herd of 80-seat leviathans, many mud-spattered from their journeys to and from Chisinau, Warsaw, Vienna, and Berlin, stood cheek-by-jowl alongside the smaller, sadder minibuses that do the milk runs to farm villages and towns in central Ukraine. Twenty-two passengers, five of them soldiers, took their seats before we rumbled out of Kyiv at 8:15 a.m.

Courtesy the author

We managed nine stops—sometimes in front of farm houses, other times in small market towns, and we had a half hour stop in the tumbledown bus station in Zhytomir. At noon the bus moseyed into Berdychiv, a town of 75,000 people, and down a tree-lined boulevard. We came to a halt in a parking lot, where a brightly painted yellow Stalinist-era train station stands across from the bus station’s ticket office. A strip of one-story kiosks selling fresh rolls, hot coffee and cellphone accessories connect the two buildings.

I looked around and thought: how the fuck am I going to find Vasily Grossman?

A white VW Passat with a taxi sign on its roof was the only car in the parking lot. I walked over to its driver, a youngish, grizzled bald man, who raised his eyebrows and read my translation app: “Do you know where Vasily Grossman lived?” “Of course I do,” he replied in English. “Get in.” His accent was thick, his name was Viktor, and he had most of his teeth. “We make one-hour tour, OK?” He asked for 600 hrynva for the hour—that’s $16—and I gave him a thousand. He smiled, pulled the taxi sign off the roof, and tossed it in the back seat.

We drove off to find the house Grossman grew up in which is at Schevchenko 14. This was a fact I learned from the historian Leonid Finberg, who had written it down for me when I visited him in Kyiv a day earlier. It was one of the few pre-World War II buildings left on the street, and I photographed the black granite plaque the city authorities (or someone) had placed there.

Viktor then drove us across town to a Holocaust memorial, which was set just behind an elegant 17th-century cathedral (Berdychiv had then been in Poland) and which I had no idea existed. We got out of the car and dodged the traffic to reach the site. “Ghetto here,” Viktor explained, and made swirling motions with his arms.

The Germans and their allies invaded the Soviet Union in the predawn hours of June 22, 1941, and the Wehrmacht was accompanied and followed by the SS Einsatzgruppen and police units. In the towns and cities closer to the Soviet Union’s western border, most Jews had no time to get away. The Jews in Kyiv fared better, relatively speaking. The Germans did not take the city until mid-to-late-September and the majority did flee. The same was true in Odessa, which the Germans and Romanians did not occupy until mid-October.

In cities like Lviv, Rivne, Brody, and Berdychiv, however, the Germans stormed into town in a matter of days and few Jews managed to escape. They were trapped, herded into ghettos, and shot, usually in forests or ravines just outside of town. There were more than a few locals who aided in this orgy of mass murder. Grossman would not find out his mother’s fate for certain until he visited the town in 1944, although he had given up hope years before.

Courtesy the author

The well-kept memorial before me had photos and plaques in Ukrainian, English, and Hebrew. There were five panels, one of which was devoted to Vasily Grossman. Every panel had a QR code, which led to more information. Together, they told the story of Berdychiv’s Jews, starting in the mid 1800s when 75% of the town’s population was Jewish, through the coming of communism, the closure of every synagogue and school, and finally the Holocaust. There was even a picture of children learning Hebrew in the 1990s, after the fall of the Soviet communist regime.

The project had been sponsored by the German Foreign Office and the research had been carried out by Ukrainian historians and the team at the Memorial for the Murdered Jews of Europe Foundation in Berlin. Petro Dolhanov, a historian in Rivne, told me that this team has been creating similar memorials throughout western Ukraine.

In the shade of a tree, I sat down and pulled out a paper copy of the letter Shtrum’s mother sent to him. I read it aloud and Viktor nodded as I read, even if he didn’t understand more than a few words.

One part of the letter summarizes the philosophy that Grossman espouses over and over:

The sadder a man is and the less he hopes to survive, the more generous, kind and good he is. The poor, the tinkers, the tailors, all doomed to death, are much nobler, gentler and wiser than those who have managed to stock up some food. Young teachers, a strange old teacher and chess player Spielberg, quiet librarians, an engineer Reyvich who is as helpless as a child, but who wants to equip the ghetto with homemade grenades—what wonderful, impractical, nice, sad and kind people they are.

Back in 1941, Grossman was sure war was coming and wanted to bring his mother to live with him in Moscow. But according to a BBC interview with Robert Chandler, one of Grossman’s translators, I learned he was living in two small rooms in a shared communal flat in Moscow with his second wife, her two sons, and their nanny. His wife did not want another person crowding them. For the rest of his life, Grossman was consumed with guilt. After his death in 1964, two letters were found. Grossman had written both of them to his mother to mark the anniversary of her death.

Viktor and I got back in the car and drove to the local memorial for the men and women of Berdychiv who have died fighting for Ukraine since 2014.

Courtesy the author

After that, we made our stop by the Church of Saint Barbara, where in 1850 the 50-year-old Honoré de Balzac, already in ill health, finally married Countess Evelina Hanska, his great love who, I’m told, cleared his debts. The aging writer then returned to Paris, where he died shortly after.

Viktor drove me back to the bus station parking lot and in a supermarket attached to it, I bought my usual: a half loaf of sliced black bread, some cheese, and a yogurt drink. There I waited for the oversize bus that would deliver me to Rivne that evening.

Vasily’s father, Semyon Osipovich Grossman, was a chemical engineer and social democrat in the years before the Russian Revolution. He married Yekaterina Savelievna, a French teacher, with whom he had one son in 1905 before divorcing. Vasily spent two years in Geneva with his mother in 1910-12, then attended university in Kyiv and Moscow where he graduated with an engineering degree in 1929. He specialized in mining and went to work in the Donbas, where Vasily Grossman grew up.

Vasily Grossman married, had a daughter, settled in Moscow and divorced in the early 1930s; in 1936 he remarried, to Olga Mikhailovna Guber. He began writing stories in the early 1930s and published two well-received novels, Glück Auf and Stepan Kolshugin, both of which told the story of Donbas miners. He had his share of battles with Soviet censors, although nothing like what was to come. Both novels made Grossman popular with the reading public.

When Germany invaded Russia in the summer of 1941, Grossman volunteered to join the staff at Red Star, a military newspaper, and worked under its editor David Ortenberg, who was sending reporters to the front. Grossman was pudgy and out-of-shape. That would soon change, but he did need to walk with a cane. He was known to be fearless, was cited for bravery, and earned the rank of lieutenant colonel. Front-line soldiers stood in admiration of him and devoured his reporting in Red Star. Grossman spent three months in Stalingrad—mostly on the right bank of the Volga, that part of the city that was attacked and bombed relentlessly. No other reporter for Red Star saw as much action as Grossman did in Stalingrad.

If you saw Jean-Jacques Annaud’s 2001 film, Enemy at the Gates, in which Jude Law plays the real life Soviet sniper Vasily Zaytsev, and Joseph Fiennes plays Commissar Danilov (who looks remarkable like Grossman), you’re watching a story snatched from Grossman’s Life and Fate. And no, there’s never been even a halfway decent film about this greatest of all wartime battles. By the end of the Second World War, Grossman had spent over a thousand days on the front lines—a period well covered in Antony Beevor and Luba Vinogradova’s A Writer at War: Vasily Grossman with the Red Army.

Aside from his front-line reporting in Stalingrad, Grossman went on to cover the battle of Kursk, the largest tank battle in history, before he entered Poland and found his way to Treblinka. Like Belzec and other “camps” in Operation Reinhard (Sobibor and Belzec), Treblinka had almost no facilities for prisoners. These camps were built as factories for Jewish mass murder. When Grossman arrived at Treblinka, he took the time to interview villagers throughout the region so he could understand the everyday operations of how these death factories functioned. His essay The Hell of Treblinka was translated and used as evidence during the Nuremberg trials. It can be found in his collection of short works, The Road.

Front-line soldiers stood in admiration of him and devoured Grossman’s reporting.

During his march westward into Germany, Grossman interviewed scores of German officers; some were Nazis, most were not. “I did not once detect in them a sense of humiliation, despair, or desire to disavow the disgraceful crimes associated with the name of Germany,” he wrote in The Road. “With extraordinary naiveté, all of them espoused the view that ‘crimes against humanity’ are not really crimes because their purpose is to benefit Germany.”

Vasily Grossman planned to publish a major novel about the war but ran into almost insurmountable problems with his editors and censors. The novel was edited crudely and took nearly a decade to come to print, finally getting published in 1952 as For a Just Cause. Grossman then turned his attention to Life and Fate, which was to be the sequel. He knew it would be his life’s work and spent the rest of the decade working on it.

No sooner had he sent the completed novel to his publisher than the KGB came calling. It was Feb. 14, 1961, and Life and Fate was essentially arrested: They took away file folders stuffed with the manuscript, his notes, and even the typewriter ribbon. He would never see them again. They even dug up his backyard to look for hidden manuscripts.

Vasily Grossman died in 1964 from stomach cancer, despondent and depressed, age 58. He had no idea that his book would indeed be published, and that The Economist would label him “the greatest bard of the Second World War.”

Before he died, Grossman gave the manuscript of Life and Fate to two sets of friends, who managed to microfilm it and spirit it out of the country. The nuclear scientist Andrei Sakharov, among others, was involved. It was published in Russian in Switzerland in 1980. That version made its way to Robert Chandler, a noted literary translator known for his work with Pushkin and Platanov. At first, Chandler refused to consider translating a novel of nearly a thousand pages. Then he started reading it.

Wikipedia

Life and Fate became a bestseller in France in the 1990s, and in addition to Chandler’s magnificent English translation, the book has been published in German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, Hebrew and other languages.

Chandler, along with his wife, Elizabeth, also managed to gain access to the entire archive of For a Just Cause. They painstakingly reinserted hundreds of censored sections and the book was published in 2019 as Stalingrad, the title Grossman had wanted. In every way, the book can now be seen as a prequel to Life and Fate. It may not be quite as powerful as Life and Fate, but its scenes at Stalingrad are unsurpassed. And the letter Shtrum’s mother sent to her son from Berdychiv makes an appearance as well.

What makes Life and Fate such a great novel? In its thousand pages, we plunge into an epic built around two sisters in the Shaposhnikov family. Through them, we meet husbands and ex-husbands, lovers and work colleagues. Grossman will introduce us to characters whom he develops in loving detail before he suddenly kills them off.

If this is sounding similar to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, you’re on to something. Grossman kept a copy of Tolstoy’s masterpiece with him during the war and was determined to produce a great work of his own. Polly Jones, a professor of Russian at Oxford University, wrote: “… to call Life and Fate a 20th-century War and Peace hardly does justice to its startling blend of taboo-breaking historical investigation, profound philosophical thought, and literary innovation. The challenges to humanity were immeasurably greater in the era of total war, atomic science and totalitarian ideology than in Tolstoy’s time. Grossman sought to capture the scale and the ethical and literary challenge of unprecedented human suffering, while rooting the drama of Stalingrad and Stalinism in the timeless struggle for humanity and the individual soul.”

I did not once detect in them a sense of humiliation, despair, or desire to disavow the disgraceful crimes associated with the name of Germany.

In Life and Fate Grossman gives us journalism, historical essays and philosophical musings, epic narratives, and a sweeping family saga. We fly with Soviet fighter pilots as they try and protect Stalingrad, we are imprisoned in the Soviet gulag and in the cells of the Lubyanka prison.

Unlike other novelists, Grossman didn’t have to imagine what Stalingrad was like because he was there. And he takes us into the ruined buildings and rubble, where we come across descriptions like this:

They walked on in silence. The boy listened to the sound of the bombers and looked up at the night sky, now decorated by red and green flares and the curved trajectories of tracer-bullets and shells. He saw the glow of the guttering fires in the town, the white flame of the guns and the blue columns of water sent up by shells falling in the Volga. His pace gradually slackened, till finally the officer shouted: ‘Come on now! Look lively!’ They made their way between the rocks on the bank; mortar-bombs whistled over their heads and they were constantly challenged by sentries.

There are also scenes of unbelievable heartbreak, such as when we meet a 6-year-old boy by the name of David, who knows what’s in store for him.

Death, who had once lived in a fairy-tale forest where a fairy-tale wolf was creeping up on a fairy-tale goat, was no longer confined to the pages of a book. For the first time David felt very clearly that he himself was mortal, not just in a fairy-tale way, but in actual fact. He understood that one day his mother would die. And it wasn’t from the fairy-tale forest and the dim light of its fir-trees that Death would come for him and his mother—it would come from this very air, from these walls, from life itself, and there was no way they would be able to hide from it.

David’s mother is killed and we travel with the child in a cattle car bound for an extermination camp. En route, a teacher by the name of Sofya Levinton tries to care for him. Here is how Grossman describes her final seconds in the gas chamber with David.

Her eyes—which have read Homer, Izvestia, Huckleberry Finn and Mayne Reid, that had looked at good people and bad people, that had seen the geese in the green meadows of Kursk, the stars above the observatory at Pulkovo, the glitter of surgical steel, the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, tomatoes and turnips in the bins at market, the blue water of Issyk-Kul—her eyes were no longer of any use to her. If someone had blinded her, she would have felt no sense of loss.

… Sofya Levinton felt the boy’s body subside in her arms. … This boy, with his slight, bird-like body, has left before her. “I’ve become a mother,” she thought. That was her last thought.

Her heart, however, still had life in it: it contracted, ached, and felt pity for all of you, both living and dead; Sofya Osipovna felt a wave of nausea. She pressed David, now a doll, to herself; she became dead, a doll.

Yet over and over, Grossman conveys to us his unshakable belief in the dignity of the individual, and nowhere is he more succinct than here:

Human history is not the battle of good struggling to overcome evil. It is a battle fought by a great evil struggling to crush a small kernel of human kindness. But if what is human in human beings has not been destroyed even now, then evil will never conquer.

Life and Fate has not aged. In fact, it is every bit as relevant now, and at times it’s downright eerie—and as painful to read as the day it was first published.

The Germans are now being expelled from Ukraine. Every day the glorious, weary earth is being liberated, as if a flood of muddy, filthy German hatred is receding and in its wake, bread is once again beginning to rise, hunched black trees, bushes and forests are straightening themselves out, and the sun and wind are drying out soil that is soaked with blood and tears. People are speaking in normal voices again and looking at the world with open eyes. Millions of people have been freed from slavery.

Ukraine was one of the fascists’ most important prizes … And now, it is in the process of losing—it has already lost—Ukraine. Fascism failed to understand (how could it possibly understand?) the strength of our people’s resistance, their great spirit and undying sense of human worth.

Edward Serotta is a journalist, photographer and filmmaker specializing in Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe. He is the head of the Vienna-based institute Centropa.