The Last Chronicler of a Lost World

Searching for Joseph Roth in wartime Ukraine

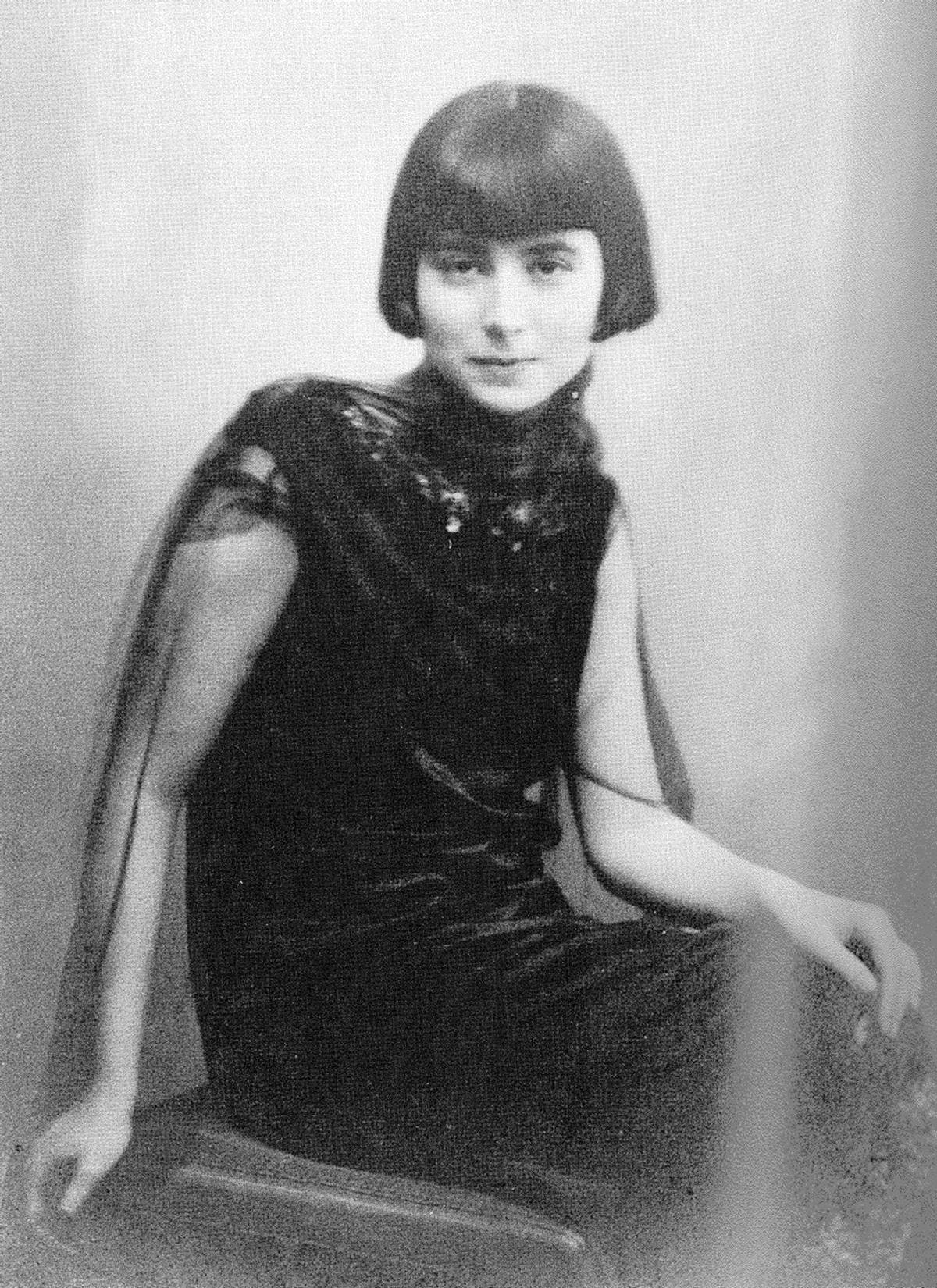

Imagno/Getty Images

Imagno/Getty Images

Imagno/Getty Images

In Wandering Jews, Joseph Roth’s 1927 collection of essays, the writer describes his hometown of Brody as a place that “begins with little huts and ends with them. After a while the huts are replaced by houses. Streets begin. One runs from north to south, the other from east to west. Where they intersect is the marketplace. At the far end of the north-south street is the railway station.”

That is the train station I came to one cool and bright fall morning, finding a small, well-cared-for and empty building, and then taking a taxi from there to the Ivan Trush Gymnasium.

This school had once been the Crown Prince Rudolph Gymnasium, named for the poor sod who was heir to the empire’s throne but decided instead in 1889 for a murder/suicide pact with a 17-year-old girl; in the years since, the school had a Polish name slapped on it in the 1920s, then became School Number Five and later School Number Two during the Soviet era, and since Ukraine’s independence in 1991 it has been named for Ivan Trush, the Ukrainian impressionist painter.

Its importance for me, however, was that this was the school that Joseph Roth attended. While children raced into the building, the first bell now ringing, I walked in and found, right in the entrance’s vestibule, an exhibition on Roth.

Moses Joseph Roth was born in Brody in 1894 and lived in a town that was predominantly Jewish. He never knew his father, Nahum, who went insane, and his mother, Miriam, who was said to be overly protective of her only child, who would go on to write The Radetzky March (1932), considered to be one of the greatest literary achievements of the 20th century.

I stood there gazing at the photographs and documents until an attractive young teacher walked by, noticed me, and said, “English?”

I nodded. “I’m Olha, the English teacher here. And I have the first period free. This your luggage? Let’s leave it in the teachers lounge and I’ll take you to our historical museum.”

And with that, we were off.

Brody had long been part of the Polish empire, but when Prussia, Austria, and Russia divided Poland in the 1770s, Brody went to Austria and became part of a province with its newly minted name of Galicia.

The town sat close to the Austrian-Russian border, and I was tickled to see an old photograph on the wall taken of that border. We see civilian couples, men in a variety of uniforms, two middle-aged women dressed nicely, and a row of barefoot children mugging for the camera, one of them wearing some sort of military uniform. Welcome to the empire, they could be saying.

The Jews of Brody, who comprised over 80% of the population by the mid-1800s, were mostly engaged in trade. That was when Brody had the status of a free trade city, but when it lost that right in the 1880s, Jews began drifting away. Quite a few settled in Odesa, and they named their synagogue the Brody Shul in honor of their former city. The Brody Shul still stands and functions, which is more than one can say about the synagogue that is actually in Brody, which is a burned hulk crying out for some sort of restoration.

Brody found itself back in Poland after the First World War, and was at the center of the Russo-Polish war that ravaged the region from 1919-20, and which Isaac Babel describes in gruesome detail in Red Cavalry.

Brody begins with little huts and ends with them.

On Sept. 1, 1939, Adolf Hitler sent the Wehrmacht into Poland from the west. Seventeen days later Stalin sent the Soviet army in from the east. Brody, like all of eastern Poland, was occupied by the Soviet Army until June 1941, when the Germans stormed in during Operation Barbarossa, and began rounding up Jews in ghettos and shooting them en masse.

The death camp of Belzec is barely a hundred miles away, and in 1942 thousands of Jewish families from Brody were gassed, burned, and buried there. Brody’s Jews were massacred and the ancient synagogue was destroyed. Little wonder that Timothy Snyder described this entire region as “the bloodlands.”

The Jewish cemetery, however, complete with enormous tombstones, was somehow spared. The European Jewish Cemeteries Initiative, an EU-funded organization that maps, fences, and documents historic cemeteries, has done a fine job with Brody’s cemetery.

Olha led me to the town square, which in earlier days, I suppose, was the marketplace Roth had mentioned. Now it consists of older one- and two-story buildings surrounding a Habsburg-era park, all well-tended with flowers, a few statues, and a coffee bar in the center.

Facing the park is an early 19th-century building that houses the city museum. I entered and glanced at the vitrine that covered the Habsburg period, then the Russo-Polish war. Another vitrine had documents and photographs of 1920-39—the Polish period—which few people in this region look upon fondly, as Ukrainian language schools and newspapers were forced to close. The Polish government took a strong stand against Ukrainian nationalism, mostly because they were peddling Polish nationalism. Those opposing Polish rule found themselves first in jails, then in pictures in the vitrine before me.

I moved on to the next vitrine, which covered the Soviet occupation of 1939-41. Those carted away for being religious leaders or wealthy men and women were pictured here. And it kept going: the Second World War and the Nazi massacres of Jews, then the Stalinist era, and finally, in the last vitrines, pictures of Brody since 1991.

Before Russia’s full-scale invasion in February of 2022, Brody had a population of roughly 23,000. Some families fled in the early days of the war, but many returned, and families from the east of Ukraine came to settle here. Being in the west of the country, Brody has suffered relatively little, although on the first day of the war a missile hit the town. That was followed by two more attacks, but compared to cities in the south and east of the country, Brody is considered safe. The military cemetery on the outside of town, however, continues to grow, as they do in every village, town, and city in Ukraine.

I walked Olha back to the school, fetched my bag, and went downstairs. As I still had my camera around my neck, a group of kids raced over, formed a semicircle in front of me, and held up their victory signs. “Slava Ukrainii” (Victory to Ukraine), I said, taking their picture. In their 8- and 9-year-old voices they shouted back “Heroyam Slava!” (Glory to the heroes).

In many ways, Roth’s tragic life mirrored Brody’s own misfortunes. In his final year in the Crown Prince Rudolph Gymnasium in 1913, Roth wrote to his cousins: “This last year will soon be over after my final exams. All the trials and tribulations of school will soon be behind me, and I will go on to the great school of life. Let’s hope I earn equally good grades at that institution […]”

He did and he didn’t. This sprightly sounding young man, about to leave the shtetl and his mother behind, would die 26 years later, in 1939, as an impoverished alcoholic in Paris in 1939.

But in that period he also became one of the most prolific, insightful, and well-paid journalists in Europe, and wrote 17 novels and novellas along with at least four books of nonfiction (most of which he wrote while sitting in cafés and drinking). But despite these professional and artistic achievements, his personal life was one of catastrophe; aside from his oeuvre, he would leave behind nothing but debts and a schizophrenic wife locked away in Austria.

When the First World War broke out in August 1914, Roth initially identified as a pacifist. Nevertheless, he enlisted in 1916 and worked as a military censor, served on the Galician front, and then returned in 1918 to civilian life in a war-weary and impoverished Vienna.

All the trials and tribulations of school will soon be behind me, and I will go on to the great school of life. Let’s hope I earn equally good grades at that institution.

Here is where Roth’s lies, fabrications, and “mythomaniac” days (as David Bronson, his first biographer, called them) began. He would claim his father was a Polish count, that he was captured and served time in a Russian prison, and that he left the army as a lieutenant, none of which was true.

What was true is that the world Roth knew had shattered completely. In 1916, the old emperor—the doddering Kaiser Franz Joseph I—died during the war he had started. His successor, Karl I, held on to the empire for two years before it collapsed. Soon after that, the victorious allies gathered in Versailles’ Hall of Mirrors to begin redrawing the map of Europe.

Roth began his journalism career in Vienna in 1919 and churned out a hundred articles before the newspaper he was working for folded. He met Friedl Reichler in 1919 and they married in the Leopoldstadt synagogue in Vienna in 1922. Friedl accompanied him to Berlin and Roth began to work for the prestigious Frankfurter Zeitung.

Wikipedia

Always short of money—his great translator, Michael Hofmann, called him “the most impractical man who ever lived”—Roth published his first novel, Flight Without End, in 1927. Zipper and His Father came out a year later and Right and Left a year after that. His first financially successful novel—Job: Story of a Simple Man, published in 1930—was certainly his most Jewish. Never again would a Jew hold such a central place in his writing, although Jews did appear in nearly every one of them and his descriptions in his novels of shtetls were surely based on Brody.

The Radetzky March, a family epic about the fall of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, came out in 1932 and is considered one of the 20th century’s greatest novels. At 369 pages, it is Roth’s longest, though that isn’t all that long for an epoch-defining piece of literature. But Roth’s other novels, often written in haste, tended to be around half that.

On Jan. 30, 1933, the day President Hindenburg installed Adolf Hitler as chancellor, Roth took a train to Paris. He would never return to Germany and, as Hofmann tells us, Radetzky March was published “nicely in time to be fed to the flames by enthusiastic National Socialist students in Berlin on 10 May, 1933.”

The peripatetic Roth would sometimes take Friedl with him on his reporting trips, but more often, he would leave her in hotel rooms for weeks, even months on end. His biographers concluded that he treated her cruelly. Because Roth always lived on the edge financially, and because he was sinking into alcoholism, Friedl’s life was made ever more insecure until it shattered. She was first taken into a clinic in Berlin, then transferred to Vienna. The novelist, biographer, and friend of Roth’s, Stefan Zweig, along with his wife, Friederike, paid some of Friedl’s medical bills and tried to find her better treatment. So did Friedl’s parents. To no avail.

She remained in various Austrian institutions until July 1940, when Friedl was sent to the infamous Hartheim Institute outside of Linz. A panel of doctors signed off on her being gassed, which was her fate on July 15, 1940.

Zweig, whose family had been quite wealthy, also helped support Roth. Roth was clearly the better writer and Zweig knew it. In The London Review of Books, Michael Hofmann, who translated many of Roth’s works, wrote that “Stefan Zweig just tastes fake. He’s the Pepsi of Austrian writing.” And while Roth seethed at having to depend on Zweig financially, Zweig never abandoned him.

The barbarians have taken over. Do not deceive yourself. Hell reigns.

Roth’s last years in Paris became ever more chaotic, as described in the firsthand account left behind by Roth’s friend Soma Morgenstern. Like Roth, Morgenstern grew up in Galicia as an Orthodox Jew before turning his back on religion. Morgenstern had also lived in Vienna and fled to Paris in 1938. He found himself in the Hotel de la Poste in the sixth district, and was delighted to learn that his neighbor was Joseph Roth, his old friend from his teenage years, when the two young men met at a Zionist youth organization.

Morgenstern’s book on Roth, Flucht und Ende (Flight and End) has regrettably not been translated, but Keiron Pim, Roth’s most recent biographer, draws on it to narrate Roth’s final days and the ghastly fight over his burial. Roth’s ultimate demise was precipitated by the death of his friend Ernst Toller, who hung himself in the Mayflower Hotel in New York on May 22, 1939. When Roth heard the news, he was badly shaken, went for a walk with Morgenstern, and returned to the Café Tournon, where he collapsed. As he lay on the floor, he mumbled twice, “I’m not baptized.”

Delirium tremens were setting in, and Roth was taken to the Necker Hospital where he was shackled to the bed when he tried to get away. Life passed out of him at 5:50 a.m. on May 27.

Courtesy the author

Morgenstern recounts the arguments about whether or not Roth had converted to Christianity. Stefan Zweig’s first wife, Friederike, who had converted to Catholicism, said that Roth had. Zweig, who was in London, could not travel to Paris just then. When he heard that Roth was buried as a Catholic and that Morgenstern and other Jews felt they shouldn’t recite Kaddish over the coffin, Zweig was shocked. When he asked how all this happened, Morgenstern replied: “Ask your ex-wife.”

The funeral was attended by monarchists, Galician Jews, converted Jews, and the journalist and communist firebrand Egon Erwin Kisch, who showed up to throw red carnations into the grave. It could all have been an opera—a grand tragedy anticipating the calamity to come: The entire world of German/Austrian Jewish intellectuals was being snuffed out, shut down or scattered to the winds. In her autobiography, the publisher Brigitta Fischer recounted:

In his memoirs, [the translator and novelist Felix] Bertaux recalls a Sunday in the Grunewald [in Berlin] with us in February 1928, when he met many of our friends: Jakob Wassermann, Alfred Döblin, Ernst Toller, Alfred Kerr, George Grosz, and Joseph Roth, who said: ‘In ten years a) Germany will be at war with France, b) if we are lucky, we will be able to live in Switzerland as emigres, c) Jews will be beaten up on Kurfüstendamm.’ No one was ready to believe the despairingly smiling Roth. But very soon his prophetic words were to come true.

All of those mentioned above (only Grosz was not Jewish) either killed themselves, died in penury, or well before their time. Such was the destruction of their world. No wonder Roth wrote to Zweig in 1933, just after the Nazi takeover of Germany, “The barbarians have taken over. Do not deceive yourself. Hell reigns.”

In Brody, I had a bowl of borscht just off the town square. Through my translation app, I asked the waitress if she knew the address where I was to catch my bus, as I had bought the ticket online. She called her husband over, who told me in English that it was actually a gas station/rest stop on the main four-lane highway around 10 kilometers away. I asked if they would call me a taxi. He laughed, grabbed my suitcase, and the two of them drove me there.

Don’t ask me why but in the same way that some people dream of opening a pub and others, like me, a bookstore, it seems that most Ukrainians dream of opening gas stations—and many of them do.

The gas station where I waited for my bus had the kind of buffet you just don’t find alongside American freeways: steamed salmon or grilled chicken breasts, kasha, Greek salad, and steamed broccoli.

A giant 80-seater with a Kyiv-Warsaw sign in its windshield sailed into the lot and came to a halt so passengers could eat, smoke, and take a bathroom break. And there I was, the old white-haired Jew loading my bag. Note to self: Go easy on the Roth, OK?

Lviv is around 80 miles away and it took three hours to get there. No one got on, but when someone needed to get off, they would stand near the driver, tap him on his shoulder and we’d slow down.

As the sun began to set, a white-orangish light flooded the bus from the west, and I watched a tall, thin soldier take his rucksack down and stand next to the driver. His uniform was spotless and perfectly ironed. He was clean-shaven. He stood there until we pulled over, and then sprang off the bus and sprinted toward a farmhouse a couple of hundred yards off.

Come on, driver, don’t go just yet, let me please see the kid get to the front door! Since the windows of the bus were so mud-splattered, I didn’t bother pulling out my camera, but it didn’t matter. The roar of the old diesel engine growled and strained and we were back on the two-lane blacktop as the sun sank over the horizon.

It was dark by the time the bus swung into the crowded bus lot just next to the Habsburg-era train station. This would have been the station Roth arrived in when he came from Brody to Lviv, and the station he went through a year later, on his way to Vienna, where he would find his calling, his fame, and his end.

Edward Serotta is a journalist, photographer and filmmaker specializing in Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe. He is the head of the Vienna-based institute Centropa.