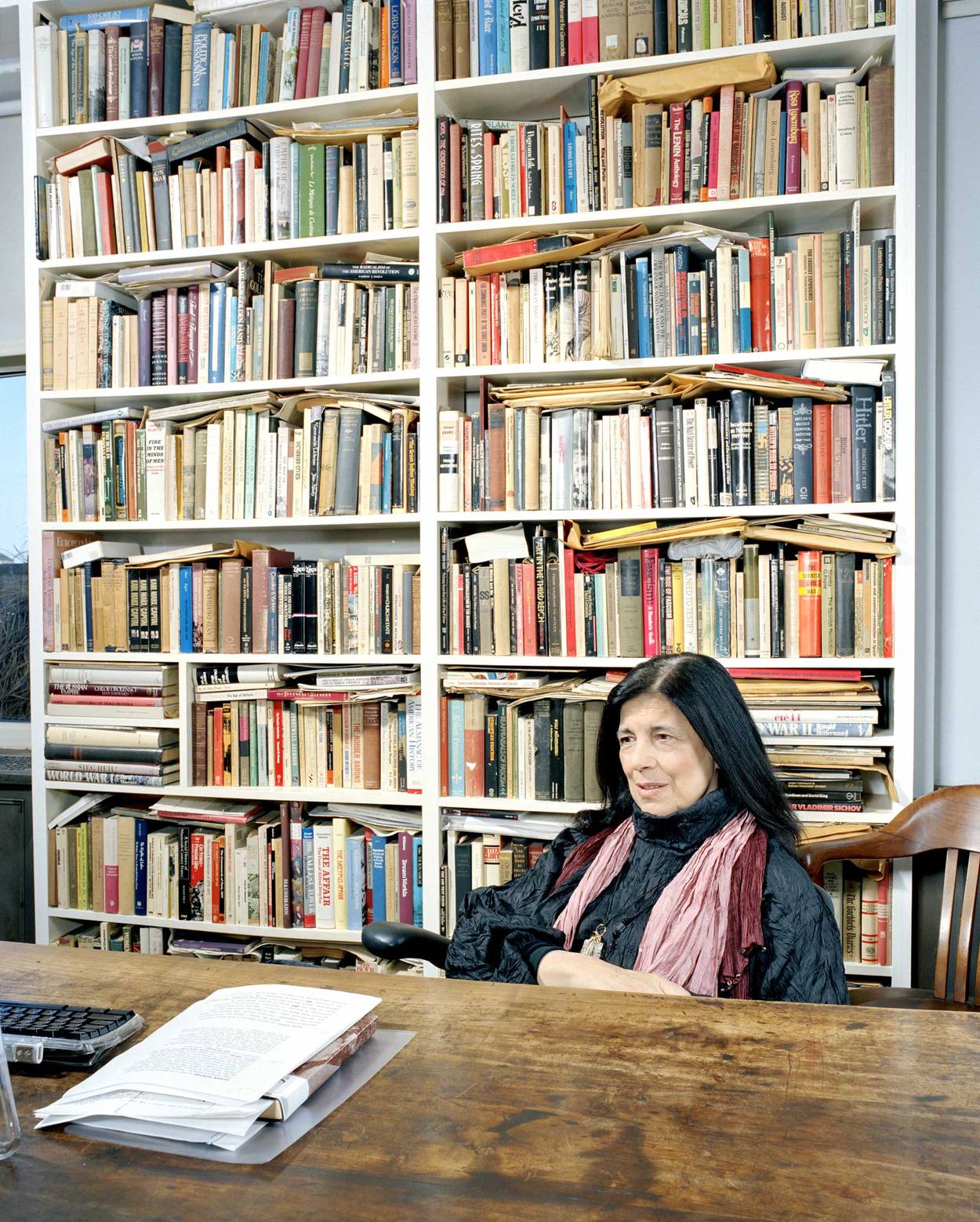

The Last Jewish Intellectuals

Susan Sontag and George Steiner star in ‘Maestros & Monsters’

Baerbel Schmidt/Contour by Getty Images

Baerbel Schmidt/Contour by Getty Images

Baerbel Schmidt/Contour by Getty Images

Baerbel Schmidt/Contour by Getty Images

“Have you ever been given an order and just followed it? Or are you incapable of keeping your mouth shut and doing what you’re told?” Susan Sontag said to a cab driver who proposed a faster way to get downtown. His response was predictable: Get out of my cab. “You can’t be serious!” a genuinely surprised Sontag exclaimed, and then trudged home through the heavy rain.

Sontag’s companions that day in the taxi were Robert Boyers and his wife, Peg. Boyers’ new book, Maestros & Monsters: Days and Nights with Susan Sontag and George Steiner, about his friendships with Sontag and George Steiner, is full of juicy stories, some more appalling than others. Steiner, though a tough cookie and at times quite snooty, was no match for Sontag the tempestuous diva, who specialized in demeaning friends and foes alike.

But Maestros & Monsters is not merely about the bad behavior of a couple of intellectuals. (How bad could they be, anyway, compared to actors, financiers or rock stars?) Boyers delivers the gossip, but he also makes a serious case for the importance of Sontag and Steiner. Both were proudly independent and unafraid to dissent. They were a different species from today’s intellectuals, who run with the herd, largely conforming to progressivism’s neo-Stalinist orthodoxy.

Vanity Fair types gravitate toward the glossy Sontag, while the far less sexy Steiner has now fallen into obscurity. Steiner reviewed hundreds of authors in The New Yorker and elsewhere, and produced scholarly books on a bewildering range of subjects. But in the glamour sweepstakes he can’t compete with Sontag, and has mostly been forgotten.

Sontag’s personality is an object of fascination, equal parts charm and callous cruelty. Jamaica Kincaid said that Sontag had “no real instinct for caring about another person unless they were in a book,” a remark Boyers quotes. Yet he was close friends with her for decades. Like Steiner, she frequently appeared at symposia hosted by Salmagundi, the literary journal that Boyers started when he was a youngster of 22.

Sontag’s willingness to offend sometimes verged on the outrageous. “I don’t think same-sex relationships are valid. The parts don’t fit,” she told an interviewer, though she spent many years with Annie Leibovitz, who wrote her a substantial monthly check (Sontag made little money from her writing). One can only imagine what Sontag would say about today’s claim that there are 200-plus genders.

Boyers justly excoriates the absurd claim made by Benjamin Moser in his biography of Sontag that she was the actual author of her husband Philip Rieff’s Freud: The Mind of the Moralist. Sontag knew next to nothing about Freud and cared less. She line-edited Rieff’s masterpiece, but only after he had written it. Moser refers to Freud as Sontag’s “first book,” a claim so silly it is amazing that Moser’s publisher let it appear in print.

Sontag’s personality is an object of fascination, equal parts charm and callous cruelty.

Sontag was not a natural teacher. “I don’t want my head filled with ‘those people,’” she told Boyers, meaning students and colleagues, after she was offered, and turned down, a position at Skidmore, where Boyers teaches. (The one time I encountered Sontag was at Yale in the 1980s, where she mercilessly berated a group of students for being at a university, a place where it was impossible to learn anything.)

Sontag the glamor tigress could be absurdly, gigantically rude. She pitched a colossal fit when Boyers, introducing one of her readings, referred to her as “Susan.” She was a sponger, too: “Whenever Susan chose a restaurant for dinner it was apt to be an expensive one, with the Boyers expected to cover the bill.” She fell out with Steiner after she failed to either thank him or pay him for some expensive rare books she made him send her from Geneva.

Sontag could also be foolish, even vapid, about politics. She had an embarrassing fling with communism during a trip to North Vietnam. Once the sheen of ’60s radicalism wore off, her politics were at times honorable and courageous (though she did, with spectacularly bad moral taste, blame America for 9/11). Influenced by her lover Joseph Brodsky, she denounced the Soviet bloc, and she made repeated trips to Sarajevo when it was under siege.

Sontag’s best essays will live on. Her renowned “Notes on Camp” is a key document of an age, as much as Mailer’s “The White Negro.” Her portraits of European intellectuals are loving and detailed. (She spent little time on Americans, though when Phillip Lopate asked her to name her favorite essayist, she snapped, “Emerson, of course.”) During the mid-’70s she wrote a few brief, gemlike essays on feminism and beauty, collected in the Library of America anthology of her work. On Photography was too suspicious of the photographer’s art, as the critic Susie Linfield has argued, but Illness as Metaphor has the comprehensive sweep that marked cultural criticism as it used to be done, before it was captured by draconian ideologies.

In Illness as Metaphor Sontag wrote, “The early Romantic sought superiority by desiring, and by desiring to desire, more intensely than others do.” Clearly Sontag was thinking of herself, with her immense appetite for aesthetic experience and her claim to superiority.

She went on to complain:

The passive, affectless anti-hero who dominates contemporary American fiction is a creature of regular routines or unfeeling debauch; not self-destructive but prudent; not moody, dashing, cruel, just dissociated.

Forty-five years later, Sontag’s assessment still rings true. American fiction remains devoted to the feckless and neutered spirit. Even a writer like the sure-footed and ingenious Ottessa Moshfegh dotes on disease-ridden indolence and seems incapable of truly dynamic creation. Visionary Romanticism still lives on in a few of our filmmakers—Terrence Malick, Paul Thomas Anderson, Kelly Reichardt. But American fiction is for the most part effete and busted, like our politics.

Like Sontag, Steiner had an unembarrassed sense of entitlement, though she was just a middle-class kid from Arizona while he spent his early childhood in Vienna, the son of a highly cultured financier. (Both attended that nerds’ Olympia, Robert Hutchins’ University of Chicago.)

In his autobiography, Errata, Steiner writes, “a systematic, doctrinal Jew-hatred seethed and stank below the glittering liberalities of Viennese culture.” The Steiners came to America, where, at Manhattan’s French lycée during the war, Steiner recalls he whispered to a classmate what his father had told him about the Final Solution, then in process: “I shall never forget her outcry and the way she sought to scratch my face. That afternoon, after class, we sat in mutual loathing and fear copying lines. Out of Virgil.”

During college in Chicago, Steiner brushed up against the real America. He writes, “When, his hand broken, his eyes virtually sealed, Tony Zale won his title fight by a somnambular knock-out of his Italian-American challenger, Zale’s mates and backers in the White City steel-mills raised and then lowered the lights of their furnaces in tribute. I will never forget the sheen of jubilation, white-yellow and smoldering red, spreading across the lake.” His roommate was a paratrooper, in college on the GI Bill, who could vault from the floor onto his top bunk. Steiner “learned a little serious poker,” and went to hear Dizzy Gillespie at the Beehive.

Anyone who doubts Steiner’s powers as a critic need only read the first few pages of his essay “Eros and Idiom,” which begins with a superb reading of a paragraph from Jane Austen and goes on to the portrayal of sex in later British and American writers. He seems to have read almost everything, and thought hard about it.

Rejecting worldly power, ruled over by gentiles, the Jewish sage was for Steiner a unique image of virtue.

Like few other critics, Steiner can tell us what an author is really about. Tolstoy’s novels, he says, “had partly been conceived in a cold agony of doubt and in haunted bewilderment at the stupidity and inhumanity of worldly affairs; but they were being taken as images of the golden past or as affirmations of the fineness of life.” He restores the edge to Tolstoy, as he does to many of the authors he wrote about.

Boyers spends little time on Steiner’s approach to Jewishness, the most fraught aspect of his work. Steiner’s most bizarre literary feat was his novel about Adolf Hitler, The Portage to San Cristobal of A.H., in which Israeli Nazi hunters find the 90-year-old Hitler hiding in a South American jungle. The book ends with a fiery speech by Hitler, where he defends his genocide on two separate counts: that he was merely imitating Jews, who in the book of Joshua were told that, as the chosen people, they must exterminate other nations; and that he meant to free humanity from the bondage that Jewish morality had imposed on it.

“Hitler’s speech calls for answers,” Steiner told Ron Rosenbaum, who interviewed him for his book Explaining Hitler. “The thousand-year reich, the nonmixing of races, it’s all, if you want, a hideous travesty of the Judaic,” Steiner commented. “But a travesty only exists because of that which it imitates.” Steiner’s perverse wish to credit Jews for creating their greatest enemy gibes with his frequent claim that Jewishness lies at the center of modernity—look, even the Nazis owe us, he was saying. (Sontag, by contrast, usually avoided Jewishness, even in the Jewish thinkers she admired, like Walter Benjamin and Elias Canetti.)

The Holocaust obsessed Steiner, and he was disgusted by gentile Europeans who minimized what their nations had done to the Jews. He wrote with pained eloquence about the persistence of Jew-hatred, and he declared the existence of Israel a “miracle” that enabled all Jews to hold their heads high. Yet he was willing to attribute Hitler’s evil to a Jewish source, rather than the poisonous dual legacy of Christian antisemitism and European nationalism that actually inspired him.

For Steiner, Rosenbaum wrote, “the fate of the Jews” was “the fulcrum, the test case of Being.” Steiner had no doubts about his own chosenness, or that of the Jews. He made over Jewish history in his own image, claiming that the Jewish diaspora, by esteeming peaceful scholarship, provided a humanistic ideal far superior to ancient Israel’s idea of nationhood. Rejecting worldly power, ruled over by gentiles, the Jewish sage was for Steiner a unique image of virtue.

Yet Steiner knew better than most the disastrous result of Jews living at the mercy of the gentile state. He witnessed the wholesale destruction of European Jewry, and he never forgot his duty of remembrance. But when he stigmatized Israel as a garrison state, “armed to the teeth,” he ignored the most pressing lesson of the Shoah. Jews had to defend themselves, move beyond psychic victimhood, and refuse to let non-Jews have veto power over their existence. None of this can be accomplished without an army, as the aftermath of Oct. 7 has reminded us.

Steiner, unlike Sontag, had a scholarly bent, and he was a born teacher. He was perhaps the most popular professor at Cambridge, which scandalously denied him a permanent position, some said because he made his students read Jewish thinkers like Freud and Lévi-Strauss. Later on, at the University of Geneva, his weekly lectures on Shakespeare attracted audiences of up to 600, many of them nonstudents who traveled from other cities to hear Steiner pick through the philological twists of a single Shakespeare play for months on end.

Steiner’s most monumental scholarly achievements are After Babel, his study of translation, and Antigones, which contains a painstaking, dazzling exegesis of Sophocles’ play. Steiner constantly pushes his reading of Sophocles toward essential insight, as in this passage:

She [i.e., Antigone], in whom palpable, if indefinable, impulses towards human interfusion are so intense, is, by virtue of Ismene’s monitory realism and the ambivalences of the chorus, made the most solitary, individual, anarchically egotistical of agents. Therein lies the bottomless irony and falsehood of Antigone’s fate.

Steiner had a genius for the utterly unexpected aperçu. He says about Sophocles, “No other poet, unless it be Blake, has brought to bear on lucid, indeed transparent, modes of statement a stronger inference of secret presences.” This insight is just astonishing—what a lightning of the mind, to bring together Sophocles and Blake!—and there are plenty more like it in Steiner’s work.

Steiner had his spates of blather. He liked to deride the modern age for its shallowness, and predictably lambasted American popular culture, though he appreciated jazz. But at his frequent best he shines light into art and culture with a brilliance at once provocative and careful.

Steiner had his wild side, too, as Sontag did not. Steiner’s most daredevil risk-taking came in his essay “The Tongues of Eros,” from his volume My Unwritten Books. Here Steiner spills the beans about “mak[ing] love in four languages” (English, German, French and Italian). Steiner’s over-the-top personal essay is full of salacious, amusing detail. He remembers a Viennese lover who “mapped her own opulent physique and that of her lover(s) with place-names derived from the capital’s various districts and suburbs. Thus ‘taking the street-car to Grinzing’ signified a gentle, somewhat respectful anal access.” A French mistress protested heartily (“Comment osez-vous?”) when he addressed her familiarly as tu, “even as I parted her comely legs.” Steiner can’t stop enjoying himself, and neither can we, his readers.

Steiner had a wicked talent for comedy along with his scholarly gravity, with hundreds of classic jokes in his repertoire, which he liked to deliver in the appropriate accents. Sontag, by contrast, was incapable of telling a joke. At times she seemed to value morose asceticism for its own sake. Her best book of essays was titled Under the Sign of Saturn—the melancholy planet, and therefore the deity of intellectuals. Her rare efforts to lighten up by name-dropping pop stars (Springsteen, the Supremes) seemed strained. Yet she had, always, a winning childlike passion for works of art. And her ardor was infectious, like that of the early Godard movies she loved.

Steiner and Sontag were two stuffed shirts, no doubt. Yet in their separate ways they took an absolute enjoyment in literature and art that has mostly vanished today, since dreary ideological pablum has taken over the humanities. Their lesson, Boyers makes clear, is that reading (or seeing a film, or listening to music) must be a headlong erotic experience, consuming your whole spirit. If you’re getting tired of TikTok, tweets, and the inane slogans that seem to have replaced thinking in the year 2023, just listen to them, and be healed.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.