Every self-respecting collector of blue-chip 20th-century design these days owns at least a piece or two by Jean-Michel Frank. The Parisian elite’s favorite interior designer in the 1920s and ’30s, Frank specialized in what connoisseurs call luxe pauvre—“impoverished luxury.” He’d wrap spindly, minimalist tables or chairs in rarefied materials—goatskin, vellum, glittery mica—to look modern, but not icily clinical. Or he’d update demure traditional forms, fashioning turned legs and flared arms out of peasanty sandblasted oak or iron with upholstery as rough as dishtowels.

Frank’s objects routinely reach five-figure prices at auction, and the buyers have included A-listers like Karl Lagerfeld, Yves Saint Laurent, and Ronald Lauder. “The market has just exploded,” reports Carina Villinger, a 20th-century design specialist at Christie’s in New York. “The refined, subdued sensibility, the absolutely magnificent craftsmanship—it’s just the taste that people with a lot of money are looking for.”

Prices could soar even higher now that Pierre-Emmanuel Martin-Vivier’s Jean-Michel Frank: L’étrange luxe du rien (The Strange Luxury of Nothingness), an in-depth monograph from Éditions Norma, has appeared, revealing Frank’s little-known life story. He was as tragic, tortured, and short-lived a trendsetter as Sylvia Plath or Oscar Wilde. Frank was plagued by drug addiction, homophobic taunts, crippling bouts of depression, and persecution by an anti-Semitic government. He committed suicide in 1941, shortly after escaping the Nazis, by jumping out of a window at his New York apartment. “He was profoundly fragile yet extraordinarily prolific,” Martin-Vivier says. “He had enormous energy and accomplished so much, in spite of these terrible forces against him.”

The historian started researching Frank for his 2005 doctorate at the Sorbonne and has now interviewed a hundred people in France, Argentina, Brazil, Tunisia, the U.S., and the U.K., including Frank family members and clients or their children. Martin-Vivier also scoured memoirs and correspondence by avant-garde artists. “Everyone Frank knew was interesting,” the author notes. The book’s essays are full of references to the likes of Jean Cocteau, André Gide, Man Ray, Elsa Schiaparelli, Cecil Beaton, Cole Porter, Alberto Giacometti, Salvador Dalí, and Luis Buñuel. Frank befriended and often designed for these celebrities, as well as for actors, publishers, politicians, and a couple of Rockefellers.

The subject attracted Martin-Vivier partly because other scholars haven’t yet shown much interest in Frank. The most recent monograph about him, by Le Figaro journalist Léopold Diego Sanchez, was published in 1980. The designer’s work has appeared in virtually none of the past decade’s blockbuster design shows. Frank didn’t like machine-age chrome, plastic, or mass production, and he wrote little and never theorized, so he doesn’t fit into the dogmatic modernist pantheon with Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius. Nor did Frank ever let loose with Art Deco chevrons and nymph forms. The Victoria and Albert Museum in London organized an Art Deco retrospective in 2003, which set museum attendance records, “but nowhere in the show or the catalog was Frank’s name mentioned,” Martin-Vivier notes. And yet, the historian adds, “he was at the absolute center of the intellectual and artistic world of his time.”

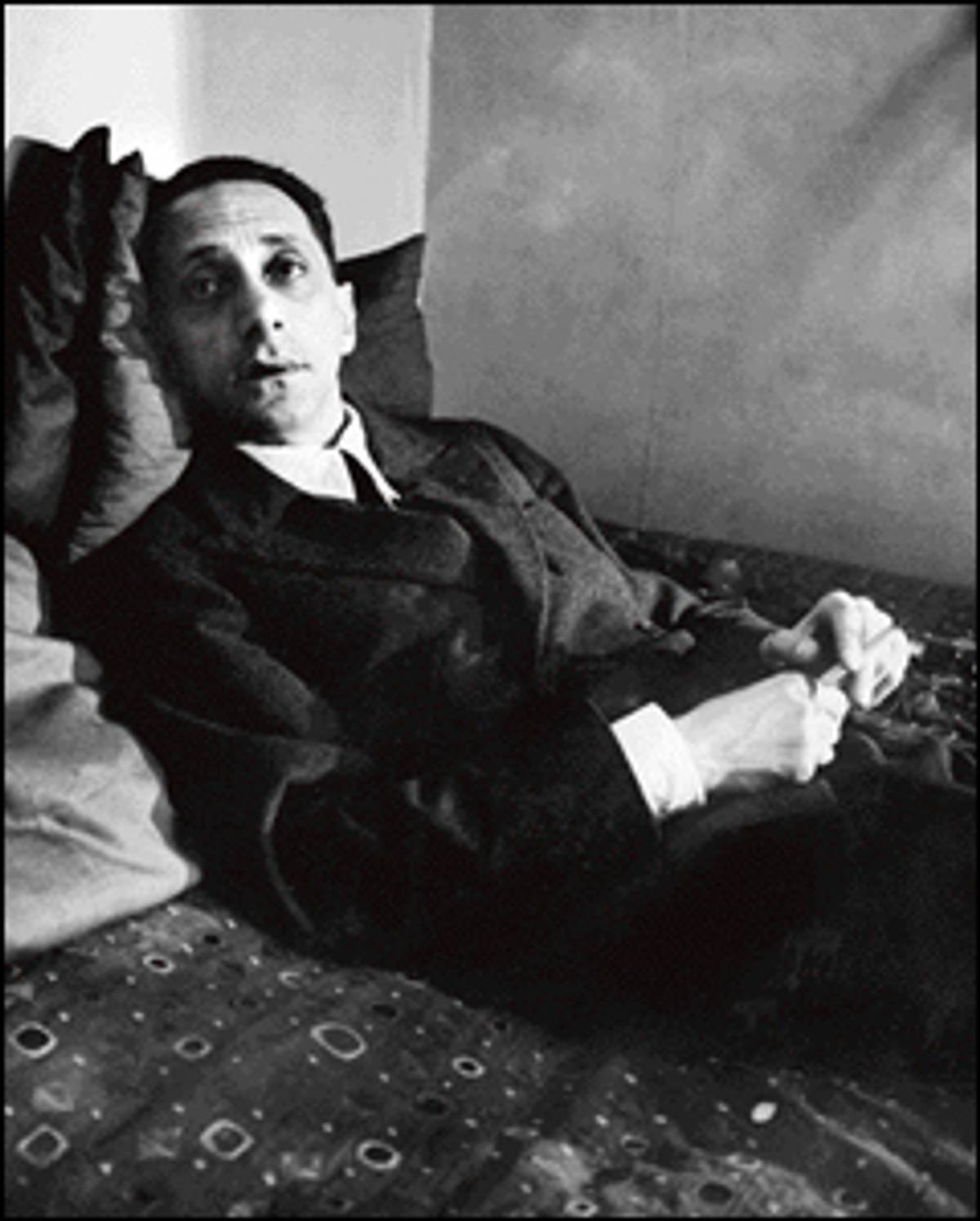

Martin-Vivier’s interviewees remember Frank as thin, short, nervous, intense, and usually dressed in gray suits. (When he attended costume balls, he dressed in drag, usually white gowns.) He had a tendency to namedrop confusingly with first names only—“Coco, Elsa, Luis”—and was imperious with clients. “Voilà, my work is done, now you can start ruining it,” he’d say, upon handing back the keys to white-lacquered rooms fitted with only a few divans and low tables. He disapproved of paintings hung on his walls, even works by Picasso, Matisse, Cranach, or Rubens.

“Very charming young man, pity the burglars took everything he had!” Cocteau is reported to have said around 1925, after dining for the first time at Frank’s Cistercian-austere apartment. White leather covered the young man’s sofas, and the walls gleamed with bits of glued-down straw. In one room stood nothing but an Hermès-leather-wrapped desk (which was the only piece of his furniture to survive World War II).

Frank had grown up in stuffier yet equally posh apartments, funded by his father Léon’s stock brokerage. Léon, a scion of a German banking family, was one of 11 children who scattered through Europe and the U.S. In 1878, he moved to Paris, and a few years later he married his own American-born niece, Nanette Loewi. Anne Frank’s father Otto was one of Léon’s nephews, and one of Nanette’s cousins. Even more bizarrely, Jean-Michel’s mother was also one of his cousins.

Born in 1895, Jean (he didn’t call himself Jean-Michel until business took off in 1930) had two much older brothers. They died at the French front within two weeks of each other in the summer of 1915. Léon committed suicide a few months later, after the French government seized his bank accounts and canceled his business deals because of his German birth. Nanette survived in a depressive fog until 1928.

Her surviving son never served in the army, exempted due to “general weakness.” A high-school classmate, Jacques Porel, wrote a memoir in 1951 recalling Jean-Michel as “a sort of child-woman, ageless and sexless,” with a mauve complexion, “oriental doll looks and a falsetto voice.” He walked on tiptoe, and spouted bits of memorized poetry or play dialogue. The other students—Porel called them “deep-voiced pimply young men drunk on brutality”—teased Frank endlessly for being not only puny and effeminate but also descended from foreigners.

After briefly studying law and serving as a businessman’s secretary, Frank started living off his inheritance, going out to nightclubs almost every night, and dabbling in interior design for cousins or friends. He also traveled to chic resorts on the Riviera and in Spain and Italy. Everywhere he went, he met and charmed people who later proved useful. Martin-Vivier’s essays lay out a dizzying array of connections and fortuitous coincidences: a school acquaintance who introduces Frank to a patron who happens to know Giacometti or Picasso or the poet Apollinaire.

Assignments trickled in to his home office: apartments for editor and shipping heiress Nancy Cunard and the modernist publisher and typeface designer Charles Peignot, fashion boutiques for Guerlain and Schiaparelli. Frank had no talent for drawing or cabinetmaking (and he occasionally had to take weeks off while detoxing in sanitariums from cocaine and opium abuse). But he had the good sense to partner with a skilled craftsman named Adolphe Chanaux. By 1930, Frank had been named artistic director of Chanaux & Co., with 30 employees at a Left Bank workshop and a boutique on the ritzy Rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré. The company hired woodworkers, varnishers, and experts in vellum, sharkskin, and straw marquetry to realize Frank’s visions. Frank also persuaded avant-garde artists to try their hands at furnishings, and thereby earn some pocket money. Chanaux distributed screens with surrealist scenes by Dalí and carpets strewn with arabesques and paisleys by the melancholy realist painter Christian Bérard. The Cuban-born architect and sculptor Emilio Terry devised Chanaux’s lines of consoles and mirror frames shaped like palm fronds, and Giacometti contributed bronze and plaster urn lamps, clamshell ceiling fixtures, and eerie sconces held up by tiny plaster fists.

No other Jazz Age designer, Martin-Vivier points out, maintained and promoted a stable of moonlighting artists. (The closest counterpart was Myrbor, a company run by collector and patron Marie Cuttoli, which produced carpets based on images by Picasso, Dufy, Miró, Léger, and Arp.) And few other designers of the time drew on so many cultural precedents. Frank’s stools sometimes resemble African hewn furniture. His tripod tables and armchairs with crisscrossed legs look neoclassical, and his low tables with scalloped trim have Chinese ancestry. Frank, as Martin-Vivier writes, “played with the codes of design and reduced styles to shadows, essences.”

Frank was fluent in German and English (his parents’ mother tongues), so he made road trips to the U.S. and South America bringing in new business. In San Francisco, Frank’s teams lined a railroad heir’s apartment in mirrors and mica to reflect a collection of animal pelts. Nelson Rockefeller commissioned a Fifth Avenue apartment from Frank with oak paneling, Giacometti’s gilded tables and Bérard’s flowery carpets. (Eventually split between Nelson and his ex-wife Mary, the interior remained largely intact into the 1990s.)

In 1939, while the Rockefeller assignment was wrapping up, all of Chanaux’s male workers were drafted. The boutique and workshop were shuttered. Frank by that time had heard from his German cousins that the Nazis were especially vicious toward Jews and homosexuals. The designer had already tried to save Otto Frank from bankruptcy, just before that branch of the family fled to the Netherlands in 1933. (Martin-Vivier studied Otto’s 1930s letters to his mother, praising Jean-Michel’s generosity.) Just before Paris fell in June 1940, Jean-Michel escaped to Buenos Aires and set up shop at an elegant hotel. He already knew some Argentine curators and arts patrons, and by September he “had found his rhythm again,” Martin-Vivier writes. Frank started weekending at haciendas, giving design lectures, and supervising craftspeople. No one knows why he moved to New York in January 1941. Perhaps to ask the Rockefellers to help his family, or to meet up with his sometime boyfriend, an American dilettante and cameraman named Thad Lovett.

On March 8, Frank’s corpse was found on the sidewalk at Third Avenue and 63rd Street. A cousin, Milly Loewi, identified the body. The New York Times ran a 100-word obituary. The relatives in Europe didn’t hear the news until after the war. A French design magazine ran some tributes to him in 1945. But by 1963 the art magazine L’oeil headlined an article, “Jean-Michel Frank, a Forgotten Decorator.”

The first generation of Art Deco collectors—including Andy Warhol and arts publisher Sandra Brant—rediscovered Frank in the 1970s. Society decorators like Billy Baldwin, Mark Hampton, and Pauline Metcalf declared him their idol. Baldwin, in his 1972 monograph, described a Frank-designed white bedspread as “entirely patternless, entirely colorless, and entirely breathtaking—full of the magic of texture on texture.”

“Le phénomène Frank” has stayed hot. Even his accessories fetch astronomical prices now: in 2003, three leather or vellum trash cans he’d provided for a Chicago-area mansion (they’d been in the house since 1932) sold for $42,000 at Christie’s. Convincing fakes of Frank designs are now turning up as well, says Villinger at Christie’s: “Unfortunately the value’s high enough now that it’s worth faking, even in the costly materials like sharkskin and ivory.” Martin-Vivier has also noticed innumerable Frank knockoffs, like his cubic armchairs and urn lamps, at stores like Ikea. (How horrified the designer would be to see luxe pauvre, crowded on tchotchke shelves at the mall.)

Academics and curators, meanwhile, are paying more attention to Frank. The Galerie Anne-Sophie Duval, a high end Art Deco gallery in Paris, has launched a retrospective to coincide with the publication of Martin-Vivier’s book, and next spring an exhibit at the Victoria and Albert Museum will explore furniture and fashion by Frank’s circle. “He’s finally being taken seriously,” the expert says. “He’s being rehabilitated.”