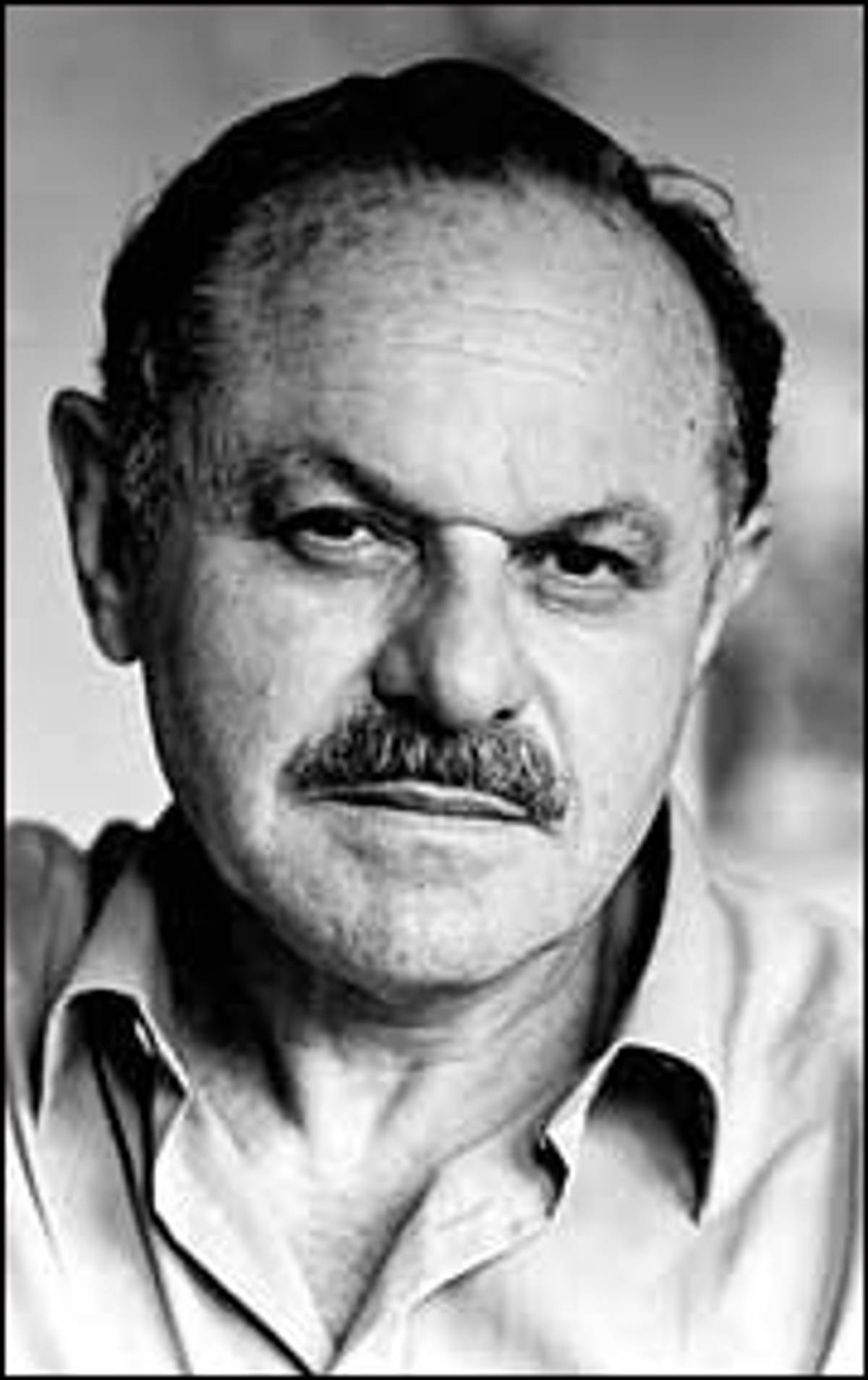

Benjamin Tammuz is a writer about whom little is known, in part because his reputation has not traveled from Israel, where he lived and wrote and was the literary editor of Haaretz, all the way to America—although it did get as far as England, where in 1982 Graham Greene named his novel Minotaur “the best book of the year.” Here is what we do know, or should know, now that Minotaur, has been published again in the United States, giving American readers the chance to find out what Greene was talking about: Tammuz was born in Russia in 1919. When he was 5 years old, his parents emigrated to Israel. He went to school in Tel Aviv, where he joined the Communist underground and the Canaanite movement, which sought to found a Hebrew rather than a Jewish state in Palestine, in order to avoid conflict with the Arabs. He studied art history at the Sorbonne; he wrote about art and culture; later in life he spent four years as the cultural attaché to the Israeli Embassy in London. He wrote eight novels, of which Minotaur is the best-known (and perhaps the finest), six collections of short stories, and eight books for children. He was also a sculptor; his monument to Israeli pilots still stands in Tel Aviv, where he died in 1989.

Now that he’s found love, you might expect that Abramov would be willing to let his arid country go, but things aren’t so simple: one of the pleasures of Minotaur is that it turns the simplest conceits—love at first sight for example—into labyrinths of psychology and circumstance, which turn deadly as we approach their hearts. Abramov romances Thea from a distance, and allows her, by means of a poste restante address, to write to him in return. Eight years pass; Thea grows up and has other boyfriends; finally she shows one of them what her secret admirer has written. “Over a thousand pages lay in the box, silent and ominous. Nikos”—that’s the boyfriend—”looked at them nervously and knew he wouldn’t be able to sleep until he had finished reading each and every one. As he took the box and carried it into his room, he had the feeling that he was carrying a corpse, and perhaps explosives, hidden in the coffin, were about to put an end to what was more precious to him than anything.” He’s right. “From the letters…Nikos knew that no man could take the place in her heart that had been acquired by the specter in letters. If the anonymous man were to present himself in the flesh and blood…” That won’t happen: Tammuz tells us fairly early in the book that Abramov is killed without ever speaking to Thea. Fortunately for Nikos, or so it seems, until the labyrinth turns us around again.

Minotaur‘s subject is the kind of love that exists between writer and reader, between writer and writer; the book is a love letter from a hard-bitten man from a faraway country. The question is: Will we be seduced? The novel puts formidable obstacles in our path. Tammuz furiously overplays Thea’s innocence: when we first see her, she has a ribbon in her hair, and “[t]his ribbon, like her hair, radiated a crisp freshness, a pristine freshness to be found in things as yet untouched by a fingering hand.” We got it with the first freshness, but it gets worse: Abramov writes in his first letter, “You didn’t recognize me. But even so, you belong to me,” and Thea somehow manages to write back, “Funny Man!… I’m writing because it’s impolite not to answer a letter as nice as yours.” It’s hard to believe that this naiveté is to be found anywhere on the planet, much less in a city with public transportation; even Humbert Humbert had fewer illusions about the psychology of young girls.

As it happens, Tammuz is not aiming for realism in the opening sections of his novel, which are short on specifics (the country Abramov spies for is never named, nor is the city where he meets Thea) and long on metaphysics (“There has been a mistake, some sort of discrepancy in birth dates, in passports. Even heaven is chaotic, like any other office,” Abramov writes). And in fact, Tammuz tells us the story of Alex and Thea several times, from several points of view; with each iteration, the details of their romance are more clearly delineated, and new facets of their story come to light. The construction evokes the obfuscations of spycraft, the wheels within wheels, which amount to—surprise—a labyrinth, with a monster in its center.

The monster, when we finally reach him, turns out to need love, as monsters often do. Looking at an engraving of a minotaur from Picasso’s “Vollard Suite,” the young Abramov observes, “From a ringside seat a woman reached out her hand as if trying to touch the dying head; a small distance remained between the extended hand and the huge head, and Alexander knew that if the hand were to touch the head the dying creature would be saved.” The repetition of “dying” and “head” is poignant and hypnotic; and the book contains many moments like this one, beautifully constructed excursuses on music or boyhood or the culture of the Mediterranean.

And yet, in the end, Minotaur‘s labyrinthine retellings are better at keeping readers out than at luring them in. Ostensibly, the abstraction of the first chapters keeps us in suspense about certain events which are only explained in full later on; but in fact this abstraction makes it hard to care what has happened, or why. We learn early on that one of Thea’s boyfriends, a certain G.R., is killed in a car accident: did Abramov engineer it? The question comes up before we know who G.R. is, and the answer comes late in the book, when we’ve already forgotten about him.

The novel is stronger as it moves from the ideal to the particular; the best part of it is the last section, “Alexander Abramov.” Here Tammuz tells the story of a wealthy Russian entrepreneur who moves to Palestine in 1921 with his pretty German wife, who soon bears a son. As Alexander grows up, he observes life in a settlement south of Tel Aviv, in all its nuances and sounds and smells, from the “scores of Arab women” who “would sit in the farmyard and peel the dry skins off the yellow almonds with their fingers and throw them into bins while their children ran about” to the settlers, who are, according to Alexander’s (Jewish) father, “simple, ignorant people who ate with their hands and ‘did not wash.’” There is no romance in this story, nor is there much love: Alexander befriends the girl he will eventually marry because she is “a good girl, diligently attended to her studies, and did not have lice in her hair.” What there is instead is life. You feel it most keenly when Alexander fights a young Bedouin, and chokes him to death:

His hands continued to press down, and he heard a faint choking sound and suddenly noticed a smell that he had not noticed all this time.

It was a smell from the man’s clothes, his body and hair. The smell of the smoke of an Arab stove that burned dung, the smell that used to fill the courtyard of their house at sunset in the days of his childhood, when the Arab workers left their work to go and bake bread and sit down to their meal. Unbeknown to his mother, he would be given pieces of warm pita by the workers, and as he ate it hungrily, he felt grains of sand being ground between his teeth.

The association is profoundly novelistic. Just as Alexander takes the Arab’s life, he’s reminded of his own participation in that life, his own love for it, even: you could probably even call the moment romantic. But this is a different order of romance: for one thing, it’s entirely physical, and for another, it’s shot through with bitter conflict. And in its very concreteness and violence it communicates to the reader something which is much more like love than are the windings in which Alex and Thea are lost.