At New York City’s Lincoln Center, major renovations are underway. The most recent of these to be completed is Alice Tully Hall, housed in the Julliard School. According to the New Yorker, the new design “shows how much richness and complexity can be teased out of the modernist vocabulary in the right hands.” Spanish musician Jordi Savall, who will be among the first to perform in the remodeled space, does not think it will take much teasing to reveal the richness of the music of the Sephardic diaspora. “Every time, I am struck by the force and the intensity of the emotion in this music,” he says.

This Sunday, after participating in an invocation inaugurating the newly appointed space, Savall and his ensemble Hespèrion XXI will perform a program called “Diaspora Sefardí: From Medieval Spain to the Eastern Mediterranean,” presenting music that originates as far back as the 15th century. But, says Savall, it’s not as simple as stamping a date on traditional music that has been passed down through 400 years via oral tradition. “You listen to a piece of Bach and you can say, ‘This is 1725 or 1730.’ But Sephardic songs you cannot say, ‘This is from 1550 or 1650.’ It’s something that’s moving. It has no date of birth and it has no date of finish, because this music is always alive.”

Although Savall, 67, is knowledgeable enough to be able to discuss every element of the music, its traceable origins—carried from Spain after the Inquisition to North Africa and much of the Ottoman Empire—and musical distinctions—“medieval but also very modern. Beautiful melodies, very strong rhythmic structures”—he prefers to think that something more emotional than technical characterizes the music. “I can imagine the music was the only thing that held these people together through terrible things,” says Savall. “Singing together with family through difficult moments is probably the most necessary thing, when you have lost everything. It’s the only explanation.”

Hespèrion XXI, which also includes Savall’s wife, the soprano singer Montserrat Figueras, was nominated for a Grammy for 2001’s recording Diaspora Sefardí, from which much of the coming performance will be drawn. They also received renown for the project Jerusalem, which brings together musicians from all over the Middle East and Mediterranean, and will be making appearances all over the world in the coming years.

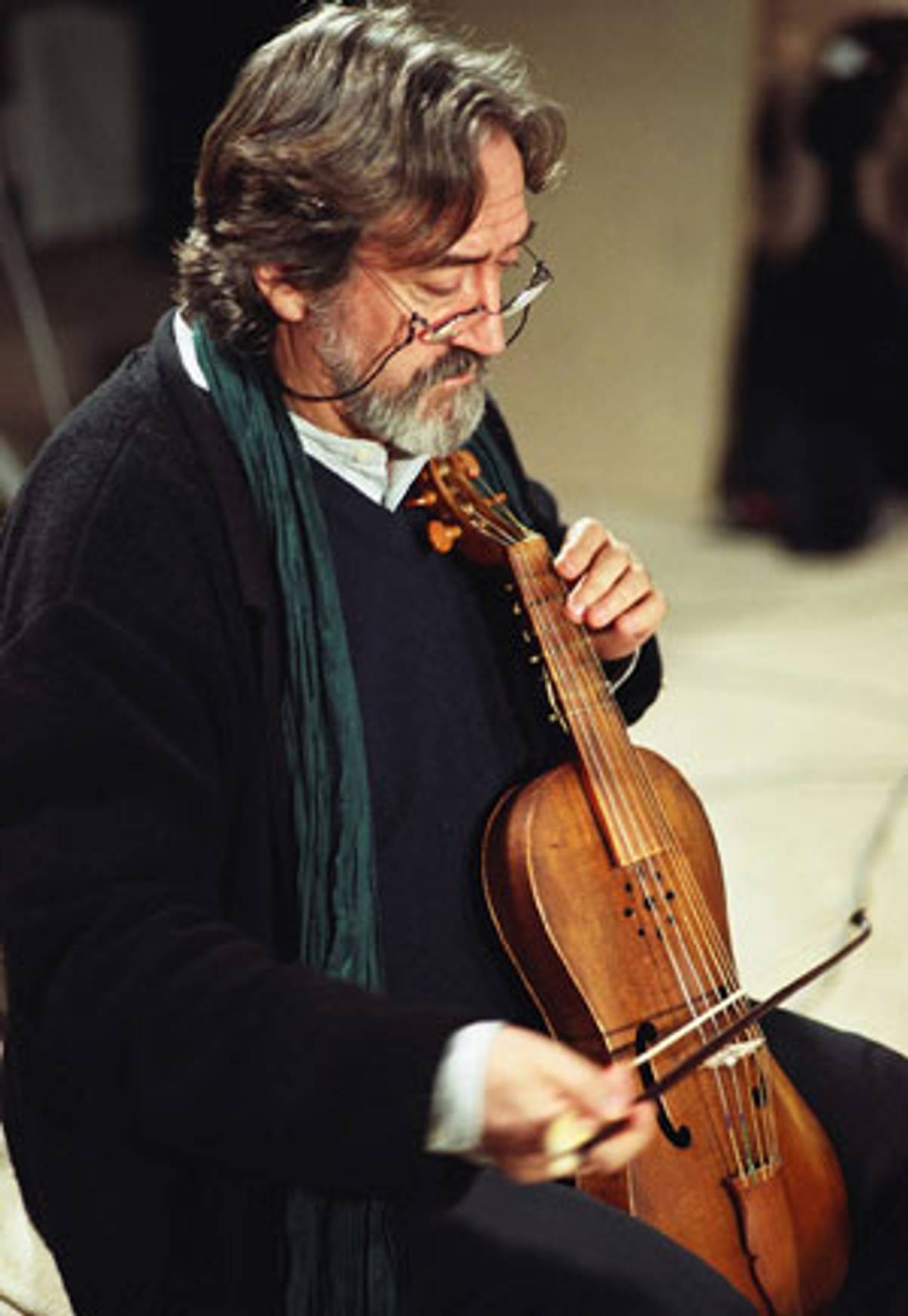

There are those that see performances of early or traditional music as opportunities for pageantry, complete with costumes and decorative elements meant to recreate the atmosphere of an era long past. Savall and his group, on the other hand, believe the music is too elemental to belong to any one time or place, and therefore they prefer to dress plainly and let the authentic instrumentation (including oud, santur, moresca, and Savall’s own viola de gamba), and a commitment to maintaining the style and speed of the music, provide their performance with authenticity. “The best thing is to be very neutral, let the music take the principal space,” says Savall. “It’s music that helped people to survive. You cannot do theatrics with this.”

Lyrically, the songs fit into an old Spanish tradition: the romance. All of them tell compelling stories, says Savall: “When you listen to these songs from the start you have to keep listening to see how it finishes.” Many of them are lullabies, including one in which a mother sings of her sadness that the man she loves is with another woman (“the children don’t know what she’s talking about.”) Another piece laments the fate of the singer’s sister, who has been imprisoned by the Moors.

People have long found innovative ways to pass on this music. Savall says there are recordings from the 1930s of old blind women singing Sephardic songs. “Blind people have a very strong sensitivity and capacity of memory. They sing it particularly for the young generations to keep alive,” says Savall. But he fears we have lost our sense of the sacredness of such transmission.

“We are used to pushing a button and hear the most beautiful orchestra,” says Savall. “When a person has to sing, he has to imagine the song inside in his spirit and has to find a way to reproduce this sound with his vocal stream. This is spiritual and physical.” Through his ensemble he hopes to at least carve out a niche for the music to be heard and appreciated. “We have to compensate the loss of this tradition by giving the music its natural space in the classical world.”

In fact, Savall believes that music has an important role to play in trying to untangle some of our world’s most confounding problems, but he is not sure we’re taking enough advantage of it. “In any civilization, when we are not able to understand people that are different, this is the detriment of the civilization. And we are now going in this direction,” he says. “Music is the most important aspect of the education for dialogue, for respect. It’s one of our last chances.”

Hadara Graubart was formerly a writer and editor for Tablet Magazine.