To Huntington Station

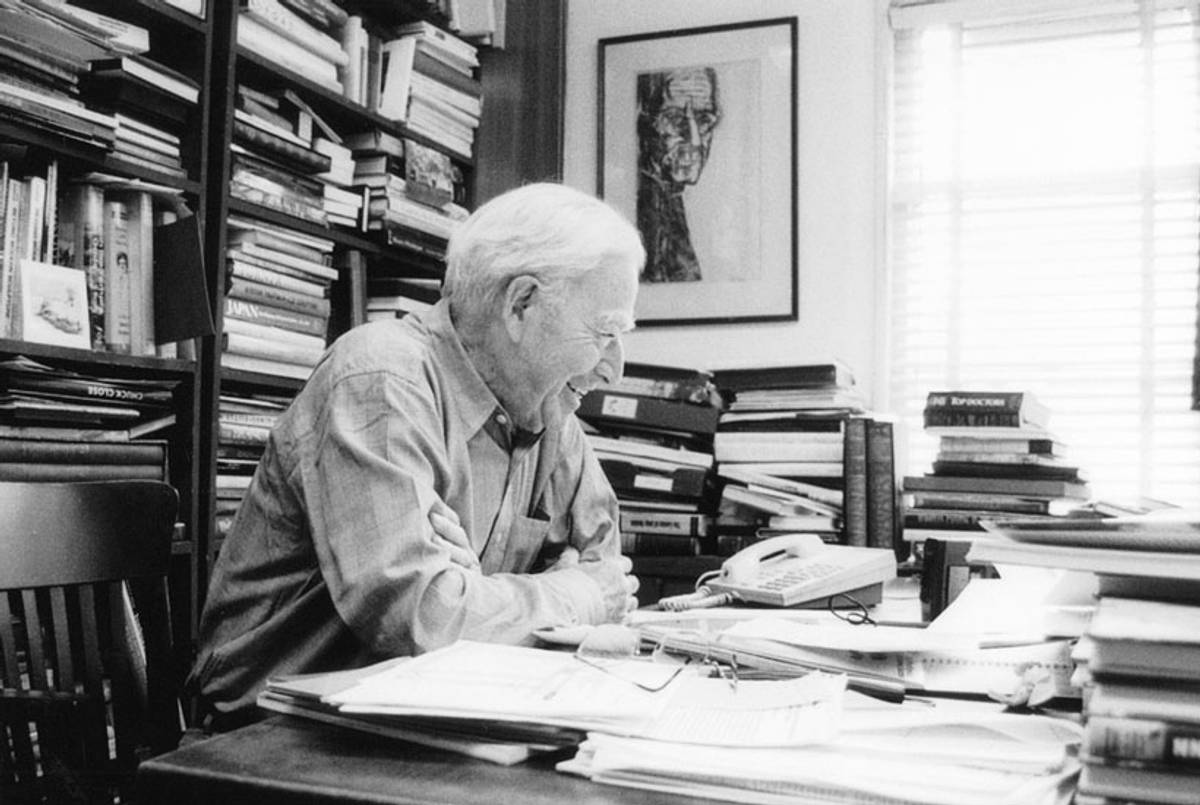

An excerpt from George Braziller’s ‘Encounters,’ the great independent publisher’s memoir, which brings to life old Jewish East New York, just short of the author’s centennial

The Street

My parents, Rebecca and Joseph Brazier, emigrated from Russia to the United States in 1900, along with millions of others who were escaping hunger and religious persecution. They—and everyone else in the shtetl of Minsk—spoke only Yiddish. Friends greeted my parents at Ellis Island and took them to a three-room walk-up cold-water flat in East New York, a poor section of Brooklyn near the border with Queens. That flat at 456 Bradford Street would be the family home for the next thirty years.

From 1890 to 1916, my mother gave birth to seven children: two girls and five boys. I was the youngest, born on February 12, 1916. My father, who had been a garment worker in a sweatshop in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, died of a lung tumor two months before I was born. My mother, my siblings, and I were packed into the small flat, which was stifling in summer and freezing in winter. We lived across from a neglected neighborhood playground, where I spent lots of time with my friends. World War I was still on, and the conditions for immigrants in a strange new land were discouraging. Still, my family considered itself lucky to have found a place to call home. My siblings and I spoke Yiddish before any of us learned to speak English.

My childhood memories of Brooklyn and East New York are of a place that is now long gone. Our family was just one of thousands of immigrant families that flooded New York with the hope of finding a better life, transforming the city’s tenements and streets into miniature pockets of Europe. I grew up in what was called the ghetto, a five- or six-block area in Brownsville, a predominantly Jewish section of East New York. The streets of the marketplace were perpetually bustling with Polish, Italian, and Russian immigrants with pushcarts, selling everything imaginable: fruit and vegetables, meat and fish, clothes and hats and underwear. From her pushcart, my mother sold pants and old shoes.

As I walked out of our flat each morning, the air was filled with the voices of people shouting in Yiddish and every other conceivable foreign tongue. The din was indescribable. When words failed to save them a few pennies, customers bargained with their hands. Each evening, the streets overflowed with the debris of the day—cabbage leaves, broken eggs, half-eaten sour pickles, stray stockings, tattered yarmulkes—which was removed by street cleaners and scavengers.

The neighborhood block parties were great fun. They were held once or twice a year between Blake and Sutter avenues. It was wonderful to see families from different ethnic backgrounds come together to get to know each other for a few hours at least. Everyone smiled, showing a willingness to be friendly. They made brave attempts to communicate with sign language when words failed, which was more often than not.

The air was filled with the smells of so many different kinds of food that it was almost impossible to decide what to try first. There was a lot of guesswork before biting into strange foods we couldn’t identify—and asking didn’t help at all because we couldn’t understand the answers. I remember tasting pizza for the first time at one of these block parties, but I tended to stick to what my mother had brought along—knishes and creplach, mostly.

During these block parties, there was a kind of unspoken truce among us kids. Normally, we avoided entering each other’s turf at the risk of bloody noses. At these times, however, we put aside our street rivalries and enjoyed the party atmosphere. There was always plenty of food to take our minds off of our territorial differences. A few of us shook hands warily, looking away.

I recall very little about my sisters and brothers in the years before I met my “new” father at age eight. I never had the opportunity to learn much about them. My mother was out all day selling items from her pushcart, and my brothers and sisters had jobs away from home. When my sisters, Rose and Ida, were only twelve and thirteen years old, respectively, they found work as towel girls in a public bathhouse. They told my mother that both men and women would often grab at them. For fear of losing their jobs, however, they said nothing.

When I was not in school, I spent most of the day in the streets, playing with friends until dark or sitting on the stoop, waiting for someone to come home. I was afraid of being alone in the empty flat. A kid named David Kaminsky (who later became famous as Danny Kaye) lived in the neighborhood. I sometimes spotted him at the corner drugstore where I hung out, although we never spoke. A born entertainer, he was then already singing comic songs and improvising dance steps.

During those childhood days, the seasons never mattered—they were fluid and only signaled a switch in the type of street games we played. In the summer, we opened the hydrants and played under the cooling spray that sparkled with the colors of the rainbow. In winter we build enormous snowmen and snow forts. I loved the evenings, when the streetlights went on, casting shadows everywhere. One of our made-up games was posing as famous people, mostly baseball players and actors. My favorite character to play was Charlie Chaplin. I didn’t have a battered derby for my head, but I enjoyed imitating his walk.

Fridays were special. I would return from school without detouring for a game of punch ball with my friends. I hurried home to clean up our flat before my mother returned. I would wash the floors and dust the table. I would prepare the kitchen table for supper, although I don’t remember any fancy dinnerware. My mother usually arrived at dusk. I would wait for her on the street corner, rushing to meet her to take the heavy bags she was carrying, which were full of the items she had been unable to sell.

I loved to watch my mother at the stove. If she had had a good day with the pushcart, there would be fish or chicken for dinner. If she had had a bad day, it would be potato soup with gizzards, bitter sour pickles, and herring. Before she began cooking, she would look around the flat, call me over, and give me a kiss, saying “Zer schön, zer gut” (“Very nice, very nice”). Soon after eating, everyone would fall into bed, dead tired. Yet, as tired as she was, before we went to sleep, my mother would always tell us stories of what it was like in Russia when she was a girl. Her stories were in Yiddish, but my sisters, who had learned English, would jokingly tease her. “Speak English! Speak English!” they would urge.

Our flat was heated only with a coal stove, which required constant fueling with coal or wood scraps. The only way to keep warm was to sit close to the stove. We bought ice from a wagon to preserve food in our icebox. The block of ice lasted only a day or two, depending on how hot the days were. When the nights were very cold, I crept into bed with my sisters. I loved their sweet smell and warmth and gradually fell asleep. In winter, school was the only place where we could be warm most of the day.

By the age of seven, I had already developed an entrepreneurial streak. The tenants on the floor of our building shared the common toilet down the hall—a typical arrangement in tenement housing. Because nearly everyone had to use the facilities at the same time each morning, I discovered a way to make a few extra pennies. When the toilet was available, I knocked on the doors of the good tippers to alert them that they should hurry to take occupancy. I showed favoritism to the parents of one of the little girls I had a crush on.

Everyone who lived in the crowded tenements tried to find ways to overcome the claustrophobic conditions. In hot weather, people climbed up to the roof with their bedding to try to get some sleep. By the end of the summer, the entire neighborhood ended up there. The Jews congregated in their own corner of the roof, and the Italians and Poles in theirs, so there was very little intermixing. Young people danced to records on the gramophone, and children played until they dropped off to sleep from exhaustion. My mother didn’t tell me stories on the roof, but she softly hummed Yiddish folk songs as I gazed up at the darkening blue sky.

Privacy was not highly valued in our neighborhood. No one had a private telephone. The only telephone in the area was located at the corner drug store, where you waited in line to enter the booth and slide the door shut. The rest of the people waiting in line would strain to overhear conversations. Some people cheated the phone company by inserting flattened pennies, instead of nickels, into the slots to pay for their calls.

Just two blocks from Bradford Street was Public School 142, which I attended from ages five to seven. One of my sisters, either Ida or Rose, walked me there each morning. The teacher gave me a couple of primers, which I didn’t know how to read. Rose helped me with them. I loved looking at picture books, although the words meant nothing.

We lived close to the neighborhood of Canarsie, where, during the 1920s, descendants of the original Dutch settlers were still farming. I loved the sounds of the Dutch street names: Van Sicklen, Van Sinderen. I would accompany my mother to Canarsie to buy fresh milk. I loved the taste of the warm milk and loved watching the cows standing in the barn so patiently. The Dutch farmers allowed me to roam around the farm. The air felt different there—fresher, like walking into a park. I liked these farmers very much. They often gave us a few eggs and potatoes to take home.

I remember being happy when my aunt, Mimmi (the word mimmi means “aunt” in Yiddish, so I simply called her that), came over to read the Yiddish newspaper, the Jewish Daily Forward, aloud to my mother. I remember seeing a photograph of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in one of her newspapers, so I just assumed he was Jewish.

On the rare occasions when my mother wasn’t working, she took me and my brothers—Charles, Ben, Michael, and Sam—by train to Coney Island. There, we enjoyed the famous Nathan’s hot dogs with plenty of mustard and sauerkraut. Those hot dogs cost only a nickel, as did almost everything else at Coney Island then: the train fare, the Ferris wheel, the rides and games at Luna Park.

Once, my brother Sam tried to teach me how to swim by holding me down under the water for several minutes, which seemed like an eternity to me. Perhaps he thought everyone learned to swim that way. He finally let me come up for air when he realized I was swallowing a lot of salt water and was half-drowned. After swimming, I always wanted to go with my mother into the women’s section of the bathhouse to change out of my bathing suit, but, smiling, she pushed me toward the men’s section.

At age eight, I was heartbroken when Ida and Rose left home to share a room somewhere. “Where are they going? Aren’t they ever coming back? I tearfully asked my mother.

Today I recall with amazement and admiration how my mother, alone after my father’s death, was able to live in that three-room flat, raise seven children, and sell clothing from a pushcart all day, during the bitter years of the First World War and the Great Depression. This memoir is a tribute to her—my dear mother, whom I loved so much.

Huntington Station

One day, when I was eight years old, my mother and I were looking at some picture books. There was a knock at the door. In walked a man whom I had never seen before. I was frightened. I can’t recall ever seeing strangers in our flat. I hid behind my mother and watched as she and the man embraced.

My mother said, “Son, meet your new father.” My father had died before I was born, and I had never heard the word “father” before—nor did I understand its meaning. I burst out crying, calling for my sisters, Rose and Ida. I ran out of the room and into a closet.

The next week, my mother, stepfather, and I moved to Huntington Station, on the north shore of Long Island. My stepfather, Jacob Gross, had lived there before he married my mother. He planned to work with his brother and my mother in a tailor shop.

During the trip to Huntington Station, the whistle of the Long Island Rail Road steam locomotive sounded scary to a lonely boy. When I asked my mother where we were going, she put her arm around me and said we were going to our new home. I said I liked the home we had and liked the playground and my friends. I asked what was wrong with where we were living. She held me tightly and wept, but didn’t answer.

At the time, Huntington Station, where we would live for the next seven years, was a rural village surrounded by farms. It was nothing like the prosperous community it is today. Many of the roads were unsaved, and street lighting had not yet been completely installed. I often went out at night to look at the sky full of stars, hoping to see a shooting star. Several Jewish families had already moved into the area and opened stores on the main street. I later learned that Walt Whitman had been born in nearby West Hills. (Today there is a shopping mall named after him on a main north-to-south artery. Hit birthplace still stands as an historic site.)

The Huntington Station public school was located about a mile away from our house on a lovely hill surrounded by trees. I still couldn’t read English very well, although I spoke it well enough. Just as they did in my Brooklyn school, the kids in my class made fun of my accent.

When I did learn to read English more fluently, I read The Pickwick Papers, by Charles Dickens. The stories were funny, and the characters so real. At age ten, I began to deliver newspapers in the morning before school started. I was often so tired I fell asleep at my desk. Still, on my report cards, my average grade was B.

The seating in the classrooms was arranged alphabetically by surname. As mine was Braziller, I was seated up front, close to the teacher’s desk. The teacher’s name was Miss O’Brien, and she made me as uncomfortable as possible every chance she got.

Miss O’Brien was young and beautiful and she was also a good teacher. She was very helpful to us kids, but she seemed to take a funny sort of pleasure in calling on me to stand and answer questions when I would have been better off remaining seated. By age eleven, I was beginning to feel the stirrings of manhood, which manifested itself with embarrassingly regular erections that Miss O’Brien could clearly see from her desk. When I stood to answer her question, I squirmed into every conclave position to conceal my erection, which was only as large as one could expect in a young boy but was obviously visible to her.

When we lived in Brooklyn, my mother loved to socialize. In Huntington, very few people spoke Yiddish, and she was lonely. So, in the evenings, I began to walk my mother to classes where she and several other people from the local synagogue learned to speak and read English. After classes, she and I practiced together.

My mother eventually became an American citizen and was very eager to vote for FDR in the 1932 election. When she went to the polls on Election Day, she received instant approval to register because she was able to show a note from her English instructor stating she had had a perfect attendance record. When she received the approval to vote, she broke out in tears, repeating, “Thank you, thank you.”

When I was twelve, my mother wanted very much for me to be bar mitzvahed. She was no more observant than many other members of the local synagogue, but she insisted that I take religious instruction from the local rabbi, Rabbi Herman, and prepare myself for the initiation into manhood. I read the Torah with Rabbi Herman three afternoons a week—for many boring and tiring weeks—and became adept at speaking Hebrew. When the big day came for the ceremony at the synagogue, my mother, who sat in the balcony behind a white curtain with the other women, was ecstatic. I and the other boys had to read from the Torah and proclaim to the synagogue, “Today I am a man.”

As each young “man” left the platform with the Rabbi’s blessing, he received a fountain pen from his proud mother and father. I didn’t receive a pen—we didn’t have the money, and I didn’t have a father. My stepfather was at home, ill. “Mama, Mama, I didn’t get a fountain pen.” I was so disappointed that I ran crying from the synagogue.

Years later, when I told this story to my friend, the English author, Beryl Bainbridge, she laughed and said, “Poor George.” A week later, a package arrived from Beryl, in which I found a beautiful fountain pen with a note that read, “Dear George, today you are a man.” I have repeated this story to several others since then, and today I am drowning in fountain pens. I have since stopped telling the story.

My teenage years in Huntington Station were reasonably happy, but, for the most part, they were wasted. I just drifted. Most of my friends were older than I was. Some had jobs, and some had gone on to college. The best I could do with my limited education was to work as a golf caddy or on local farms. My stepfather died, I was fifteen, so I tried to help my mother however I could.

Somehow, I had the same feeling in Huntington Station that I had in East New York: a feeling of emptiness at the end of each day. There was one one to ask me, “What did you do today?” or “What did you learn today?” or anyone to tell me what was right or what was wrong. There was no one with whom I could share my feelings, which I can only describe as feelings of desolation. In Huntington, I learned to miss a father.

When my mother said to me one day, “We are going back to Brooklyn to live,” I was happier than I had been in a long time, although I would miss my friends and the times spent in Huntington.

From George Braziller, Encounters: My Life in Publishing. Copyright © 2015 by George Braziller. Reprinted with the permission of George Braziller , Inc., www.georgebraziller.com. All rights reserved.

George Braziller is the Brooklyn-born founder of the independent publisher bearing his name, specializing in literary fiction, poetry, and nonfiction.