How Our Pious Literary Guardians Erase Ugly Truths and Leave Us Confused

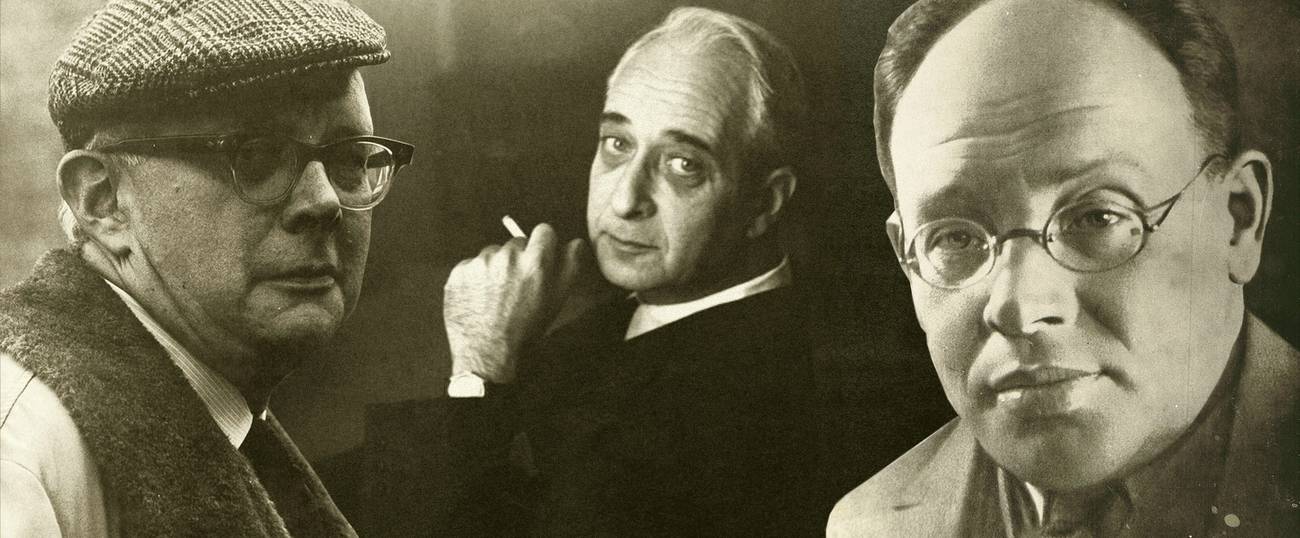

Lionel Trilling saw Isaac Babel as he imagined or wanted Eastern European Jews to be, not as he really was

In his 1946 Introduction to The Partisan Reader, Lionel Trilling, who died 40 years ago today, lamented the disregard of serious literature in American cultural life: “Unless we insist that politics is imagination and mind,” he wrote, “we will learn that imagination and mind are politics, and of a kind we will not like.” Trilling pointed to the underlying cultural matrix of beliefs, values, and mental tendencies whose literary expression becomes the foundation of political action. We ignore this, Trilling insisted, at our peril. At stake, he thought, was nothing less than the nature of American democracy. Through his many books and essays, Trilling himself contributed to such a politics and helped shape not only a sensibility within American political discourse but also an important dimension of diaspora Jewish identity that remains a significant factor in Jewish life today.

The work of Isaac Babel, which Trilling wrote about in his Introduction to Babel’s The Collected Stories, published in Walter Morison’s translation in 1955, illustrated the connection between mind, imagination, and politics perhaps more directly than even those writers he chose to examine in The Liberal Imagination (1950). “No event,” Trilling asserted, “in the history of Soviet culture is more significant than the career, or, rather, the end of the career, of Isaac Babel,” and he sets Babel’s writing directly against the interests of the Soviet state: “But no reason for the last stage of the extinction of Isaac Babel is needed beyond that which is provided by his stories, by their method and style. If ever we want to remind ourselves of the nature and power of art, we have only to think of how accurate reactionary governments are in their awareness of that nature and that power.”

Studying Babel in 1970 at Columbia University, I found Trilling’s portrait of Babel both satisfying and useful as a kind of internal guide in those politically turbulent times. He helped to codify a particular view of Jewish life in both Russia and America and provided a paradigm for self-knowledge, a set of certainties, for which, as an undergraduate, I felt a desperate need.

Trilling confesses in his Introduction that the improbabilities at the heart of Babel’s stories of a bespectacled Jew participating in the brutality and cruelty of the 1920 Polish-Russian war “alienated and disturbed” him. An “anomaly” lay “at the very heart of the book, for the Red Cavalry of the title were Cossack regiments, and why were Cossacks fighting for the Revolution, they who were the instrument and symbol of Tsarist repression? The author, who represented himself in the stories, was a Jew; and a Jew in a Cossack regiment was more than an anomaly, it was a joke, for between Cossack and Jew there existed not merely hatred but a polar opposition.”

Trilling finds particular evidence for his picture of Babel’s anomalous fate in the story “My First Goose,” in which the young recruit stands in awe of the “masculine charm of the brigade commander Savitsky” and observes, in a detail Trilling especially notes, that his long legs were “like girls sheathed to the neck in shining riding boots.” Trilling attempts to make sense of the narrator’s professed envy of the “iron and flower of [Savitsky’s] youthfulness” by suggesting that the narrator/Babel—the puny, intellectual, feminized Jew—is overcome with a kind of boyish love for the raw masculine grace and power of his eternal enemy.

***

The idea of the otherworldly nature of Eastern European Jewish life, or that Jewish culture inherently shunned violence and the Cossack ideal of masculinity did not originate with Trilling. These ideas were already well-established in some quarters of Jewish thinking since the biblical story of Jacob and Esau, and they formed a background, as he readily admits, for Trilling’s encounter with Babel. What is new is Trilling’s perception that Babel idealized and admired Cossack manliness, animal grace, and capacity for violence.

According to Trilling, the primitive Cossack presented himself to Babel as the “man of enviable simplicity, the man of the body—and of the horse, the man who moved with speed and grace.” This “man of the body,” is a symbol, Trilling continues, “of our lost freedom which we mock in the very phrase by which we name it: the noble savage.”

Since the publication of Babel’s 1920 Diary in 1996, it is impossible any longer to hold such a view of Babel’s Cossacks. They were, Babel wrote, “wild beasts with principles.”

What sort of person is our Cossack? Many-layered: looting, reckless daring, professionalism, revolutionary spirit, bestial cruelty. We are the vanguard, but of what? The population await their saviors, the Jews look for liberation—and in ride the Kuban Cossacks.

Trilling interpreted Babel’s work in accordance with what he thought Jewish history had been and who he thought the Jewish people of Eastern Europe and Russia were and in doing so was guided by clichés and stereotypes every bit as damaging and false as those foisted upon the Jewish people over the centuries of anti-Semitism.

Many of these stereotypes can be found, remarkably, in the diametrical opposition Trilling constructed between the Cossack and the Jewish worlds: “The Jew conceived his own ideal character to consist in his being intellectual, pacific, humane. The Cossack was physical, violent, without mind or manners.” Trilling is so committed to the picture of the otherworldliness of “the Jew” that he cites approvingly Maurice Samuels’ preposterous assertion “that in the Yiddish vocabulary of the Jews of eastern Europe there are but two flower names (rose, violet) and no names for wild birds.”

The “intellectual, pacific, humane” Jew is the Jew of a certain ideal promoted in much of American Jewish life—thoughtful, peace loving, virtuous, devoted to family and humanity at large, most famously enunciated by Abraham Joshua Heschel in his 1946 essay “The Eastern European Era in Jewish History,” in which he writes of “poor Jews [who] sit like intellectual magnates” with empty stomachs but heads “full of spiritual and cultural riches.” It was an image fostered by many Jewish intellectual and religious leaders still reeling from the devastation of the Holocaust and searching for a place at the table of humanity. It is also paradoxically a self-image that accords with Hannah Arendt’s portrait of Jews’ going to their death in the Nazi death camps like “sheep to the slaughter” unable and unwilling to defend themselves: Jews as victims; Jews who will not fight back; Jews who passively accept whatever murderous fate is meted out to them.

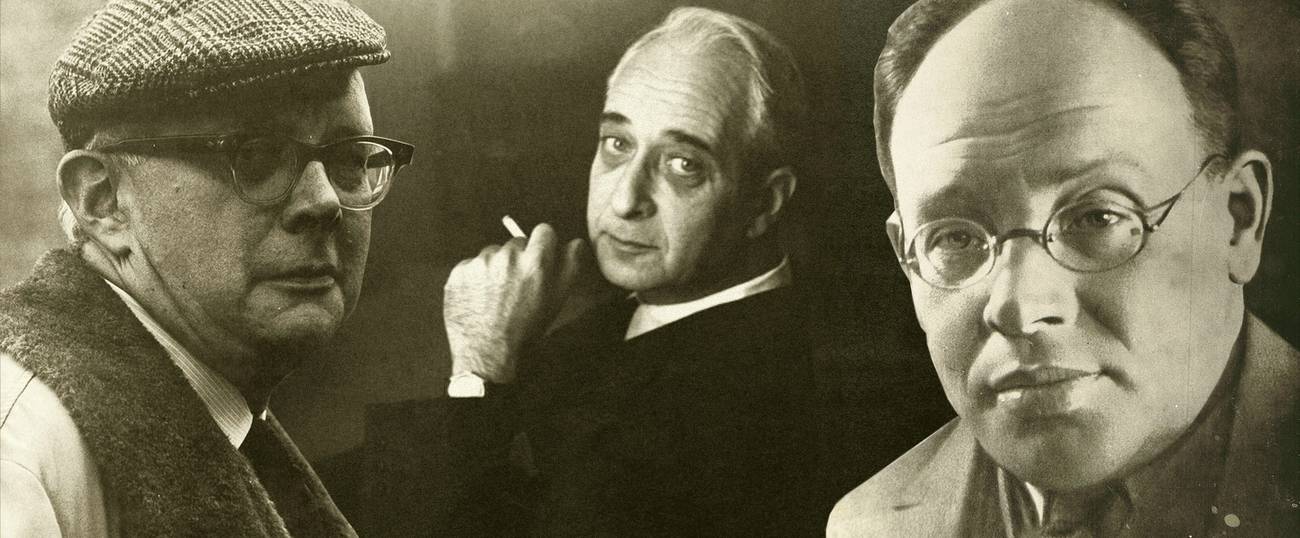

There was a politics to this “mind and imagination,” and writers like Trilling, among whom Irving Howe would certainly be numbered, consciously or unconsciously reinforced it. Most famous for World of Our Fathers (1976), Irving Howe also edited several anthologies of writing from the Yiddish. Voices From the Yiddish: Essays, Memoirs, Diaries (1972) collected writings from numerous sources and was meant to encompass the Yiddish writers who deeply felt “the over-arching problem of Jewish destiny: the meaning, the mystery, the possibility of Jewish survival.” Howe and his co-editor Eliezer Greenberg add: “It cannot be otherwise.” On the one hand, the voices collected in this anthology were meant to represent the views of Yiddish writers; on the other, the collection itself formulated an image of Jewish life and thought that reaffirmed Trilling’s stark contrast of the Jewish-Cossack worldviews.

One indication of this is the inclusion of the Heschel essay quoted above and the absence of Ze’ev Jabotinsky (1880-1940), Revisionist Jewish leader, founder of the Jewish Self-Defense Organization in Odessa and Irgun. Jabotinsky, who dressed himself and his followers in a brown uniform and were called “brown shirts,” coined the concept of the Iron Wall that should separate Jews and Arabs in Eretz Yisroel. No one would argue that Jabotinsky, who wrote in Yiddish and Russian, was not a crucial voice in the “over-arching question of Jewish destiny.” Menachem Begin was Jabotinsky’s immediate successor, and the Likud Party today maintains the tradition of his political thought. The omission of Jabotinsky from the ranks of Yiddish thinkers in Howe and Greenberg’s anthology is significant and noticeable for its political intent, but what is far less noticeable is that the work of another writer, with an unpalatable sensibility, was subtly bowdlerized in the Howe-Greenberg volume.

In their introduction, Howe and Greenberg note that Hayim Zhitlowsky was a “once influential ideologist of Yiddishism. His prose lacks the lightness and muscularity of Peretz’s and Greenberg’s; there is a touch of the library in everything he writes.” In other words, though they couldn’t leave him out of the anthology, they don’t recommend him highly. His prose, they note, is “often rather heavy, suggesting the difficulties of a writer who by inclination should have been a professor but by obligation became a publicist.” All this may be so, but it hardly detracts from the fact that he was an important force in Yiddish culture, a lifelong friend of S. Ansky, and a powerful commentator on Jewish life in Eastern Europe.

Without heeding Howe and Greenberg’s reservations, I turned to Zhitlowsky’s essay in their volume because I found his perspective challenging when I had first encountered it in Lucy Dawidowicz’s collection The Golden Tradition (1967). Dawidowicz noted that the first publication of Zhitlowsky’s writings provoked outrage. He was called a Jewish anti-Semite in the press, and even Simon Dubnov thought his work “beneath any historical standard.” Zhitlowsky poses a problem that Dawidowicz to her credit did not wish to edit out, smooth over, or ignore.

Howe and Greenberg, in fact, merely reprint the Dawidowicz translation of Zhitlowsky’s “The Jewish Factor in My Socialism,” from The Golden Tradition. Dawidowicz is credited as the translator, and nothing suggests that this is not the same essay, yet when I began to read it, it seemed to me I was reading something different. I immediately checked the Dawidowicz text in The Golden Tradition. Sure enough they were different.

Dawidowicz’s text begins as follows: “There was a time when I called myself a ‘cosmopolitan,’ an ‘internationalist,’ for to me both names signified the same thing: the antithesis of a ‘nationalist,’ a ‘patriot,’ a ‘chauvinist,’ which I thought were synonymous.”

Howe and Greenberg’s text begins: “From my friends I learned about socialism, which in their proud conviction was the last word in scientific knowledge.”

Puzzled inspection of both texts eventually disclosed that the Howe and Greenberg was indeed the same as the Dawidowicz, except that Howe and Greenberg had silently edited out the first three pages. Perhaps this was in the interests of saving the reader some of Zhitlowsky’s “heavy prose.” Perhaps, however, the problem lay elsewhere.

Devotion to the State of Israel or ritual observance cannot make up for the lack of fundamental truthfulness about our history.

In the first three pages, before “From my friends I learned about socialism,” the reader learns about Zhitlowsky’s childhood and the conditions of his life that caused him to turn toward socialist ideology. Instead of the usual story about lower-class origins or the poverty and deprivation experienced in the Pale of Settlement that is ordinarily given to explain why so many young Jews embraced radical politics, Zhitlowsky notes that his family had “many business associations with Polish landowners” and appeared to be what might be considered middle class. Zhitlowsky also rejects the notion that his socialism derived from reading Engels, Marx, LaSalle, and other important writers—whom he had not read at the time—or from the Jewish religion, which he states “was of no interest to me.” Rather, his socialist proclivity seems to have been fueled by what he calls a “heart-idea,” that is an idea that came out of his experience of life.

From home I acquired Jewish patriotism and a rather strong anti-Russianism. Jews? Aha! No joke that Jewish Gemara-head! The Jewish heart! Moses Montefiore! Moses Mendelssohn! Beaconsfield! Russians? Our whole environment was completely permeated with hate for Russian landowners and officialdom that milked us dry, conscripted our children for the army, persecuted us in every way possible, and treated us like dogs. As for the Russian masses, we regarded them as brute animals. My father, particularly, was anti-Russian. We had only fiery hate for the power wielders, ridicule and contempt for the whole people. There was no other name for a Russian than the derogatory epithet “Fonye”—“Fonye thief,” “Fonye murderer,” “Fonye drunk,” “Fonye louse.” […]

I will never forget those evenings when our handyman, a Russian peasant, sat in the corner of our dining room, his plate on his knees, while my family regaled itself at table with jokes about Jews outwitting the stupid Russian peasant. […]

From our way of life, I first understood the true meaning of exploitation, that it was a way of living at the expense of someone else’s labor. All the merchants, storekeepers, bankers, manufacturers, landowners, both Jews and Gentile, were exploiters, living like parasites on the body of the laboring people, sucking their lifeblood, and condemning them to eternal poverty and enslavement. […]

Yet it was true that, with very few exceptions, Jews engaged in exploitation and led a parasitical existence. But the blame lay not on our lack of civil rights, but rather on the whole social order. Both antisemites and philosemites would have to disappear, because they belonged to the old world.

This scathing, passionate, deeply felt critique of Zhitlowsky’s own Jewish past is what Howe and Greenberg left out and it is difficult to believe they did so for reasons of style. Zhitlowsky’s picture of his crude, inhumane, and unenlightened family defiantly contradicts Trilling’s “Jew” and Heschel’s “magnates.” Howe and Greenberg could not, it seems, admit into their lexicon of a virtuous past of victimization and struggle the idea that Jews—just as Russians and Poles—could “engage in exploitation and [lead] a parasitical existence. ”

Writers such as Sholem Asch and Philip Roth fought against such erasure of their concrete experience of life; and their efforts were frequently met with much the same denunciation, condemnation, or neglect (see Irving Howe’s attack on Roth in Commentary magazine, 1972) to the point of virtual excommunication. A comparable fate often greeted the maskilim in the 19th century who also proposed an alternative narrative of Jewish history. Ansky, author of The Dybbuk and childhood friend of Zhitlowsky, for instance, wrote of his being literally driven out of a Jewish town for daring to distribute certain “enlightened” literature. The “intellectual, pacific, humane Jew” who had no words for wild birds or flowers could often not tolerate any challenge to his iron-forged worldview; nor could many of his latter-day secular brethren in the United States who helped perpetuate a self-mutilated Jewish narrative for generations of young Jewish Americans about the world and themselves.

Much ink and money is spilled in the Jewish world today on “the over-arching problem of Jewish destiny: the meaning, the mystery, the possibility of Jewish survival,” but without a truthful and unedited understanding of our past only sham, hypocrisy, and failure await us. Devotion to the State of Israel or ritual observance cannot make up for the lack of fundamental truthfulness about our history.

The prophet Hosea wrote: “My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge.” Perhaps we may begin to understand this in the terrible disorder in the Jewish world today, the inability to grasp the violence and intransigence of extremist elements in Israel and elsewhere amid the nostrums of superficial piety and the disaffection of our youth, the lack of real leadership and the smothering anxiety over a future that may overwhelm us. Babel’s texts are a storehouse of Trilling’s “imagination and mind” set against the cruel realities and brutish politics of his time, yet the most destructive politics may not be those formulated in the Kremlin but those formulated through the clichés, unexamined assumptions, and stereotypes that guide the pious guardians of the real.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jonathan Brent, the executive director of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, teaches at Bard College. He is the author of Inside the Stalin Archives and Stalin’s Last Crime.