Two-Family Home

The French ambassador to Israel’s distinctive residence in Jaffa tells the story of an unusual—and eventually ruptured—friendship between a Jewish Zionist architect and his Arab Muslim client

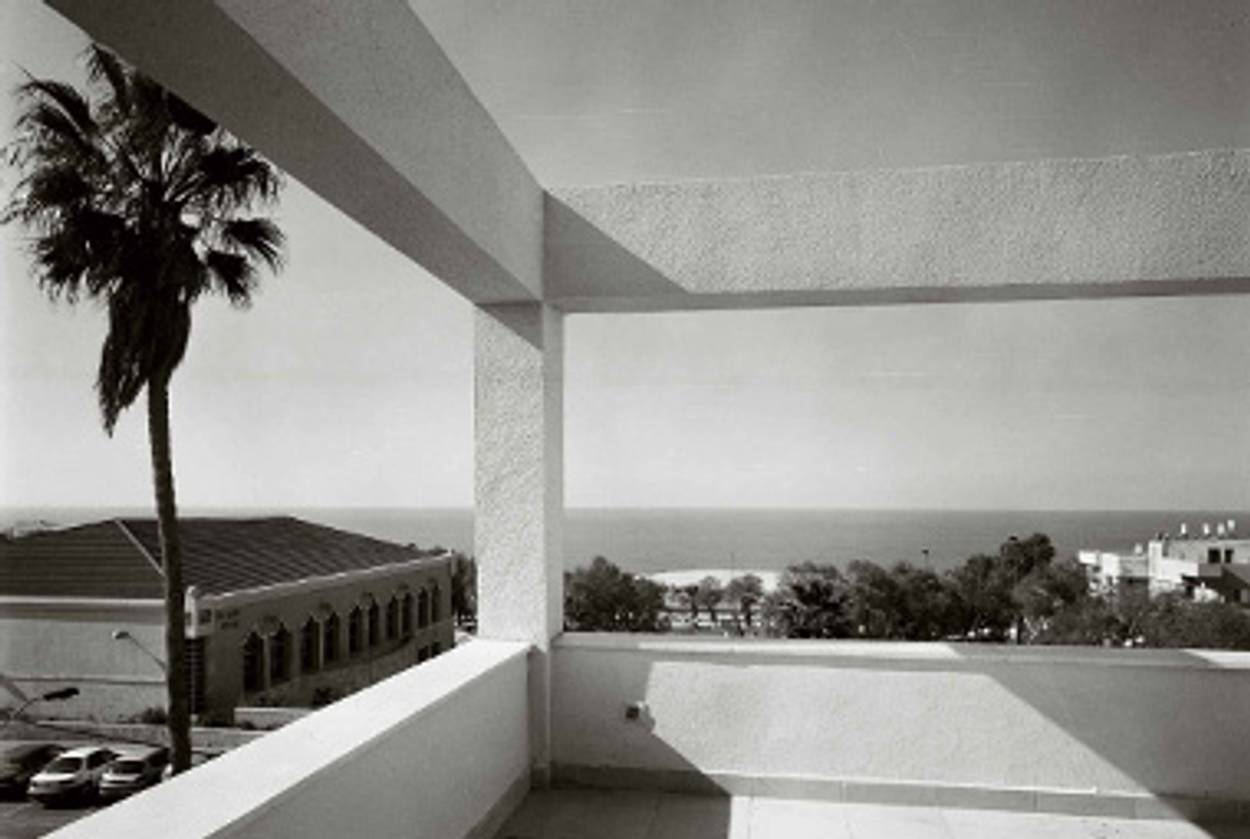

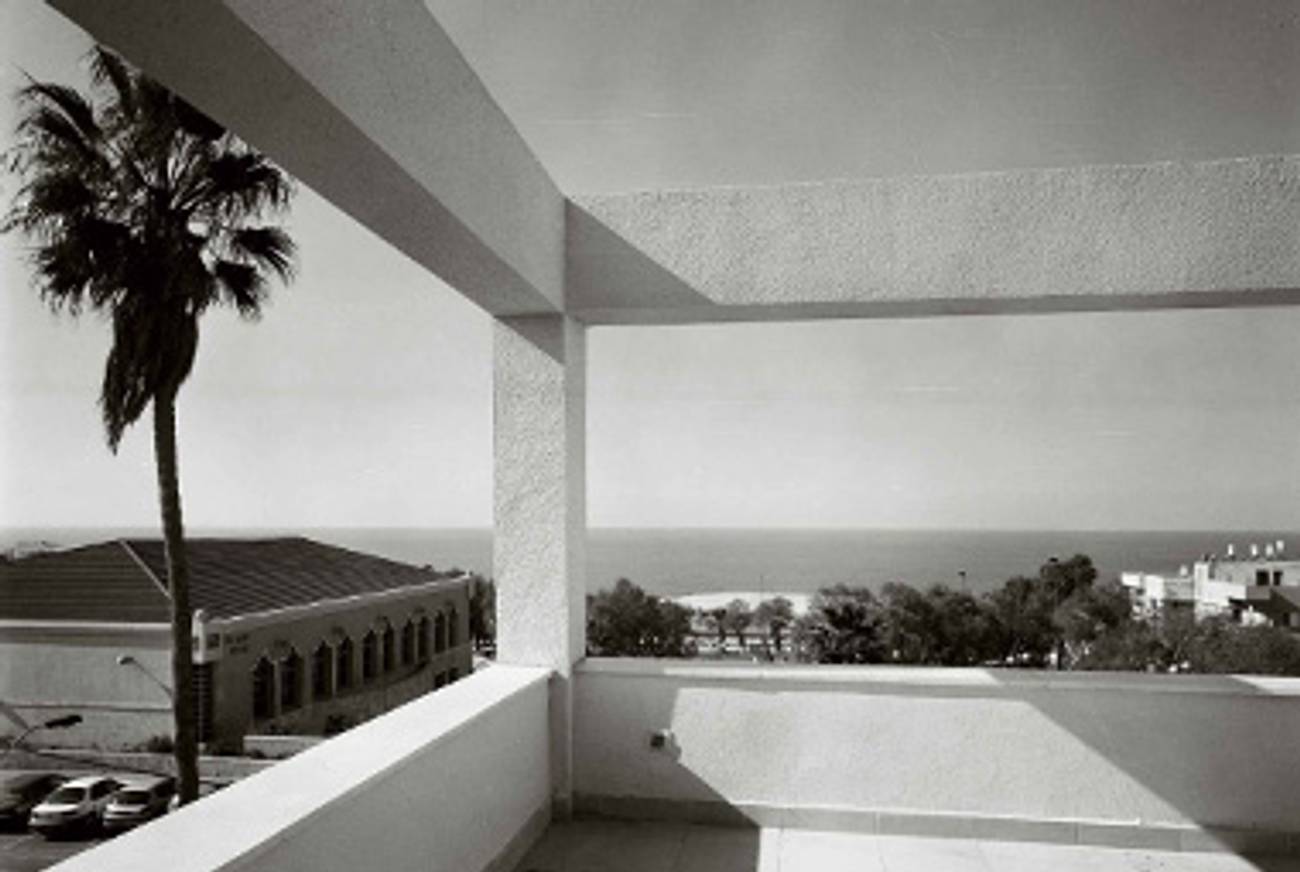

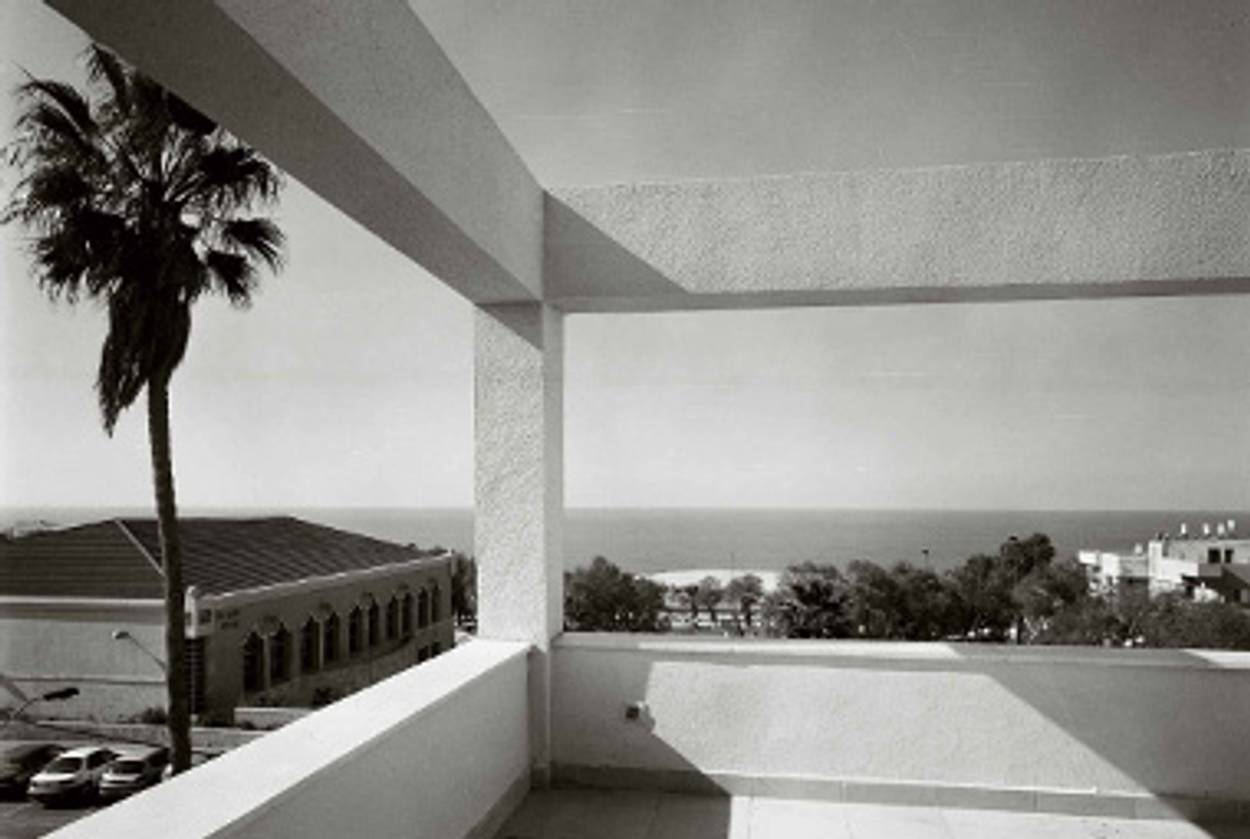

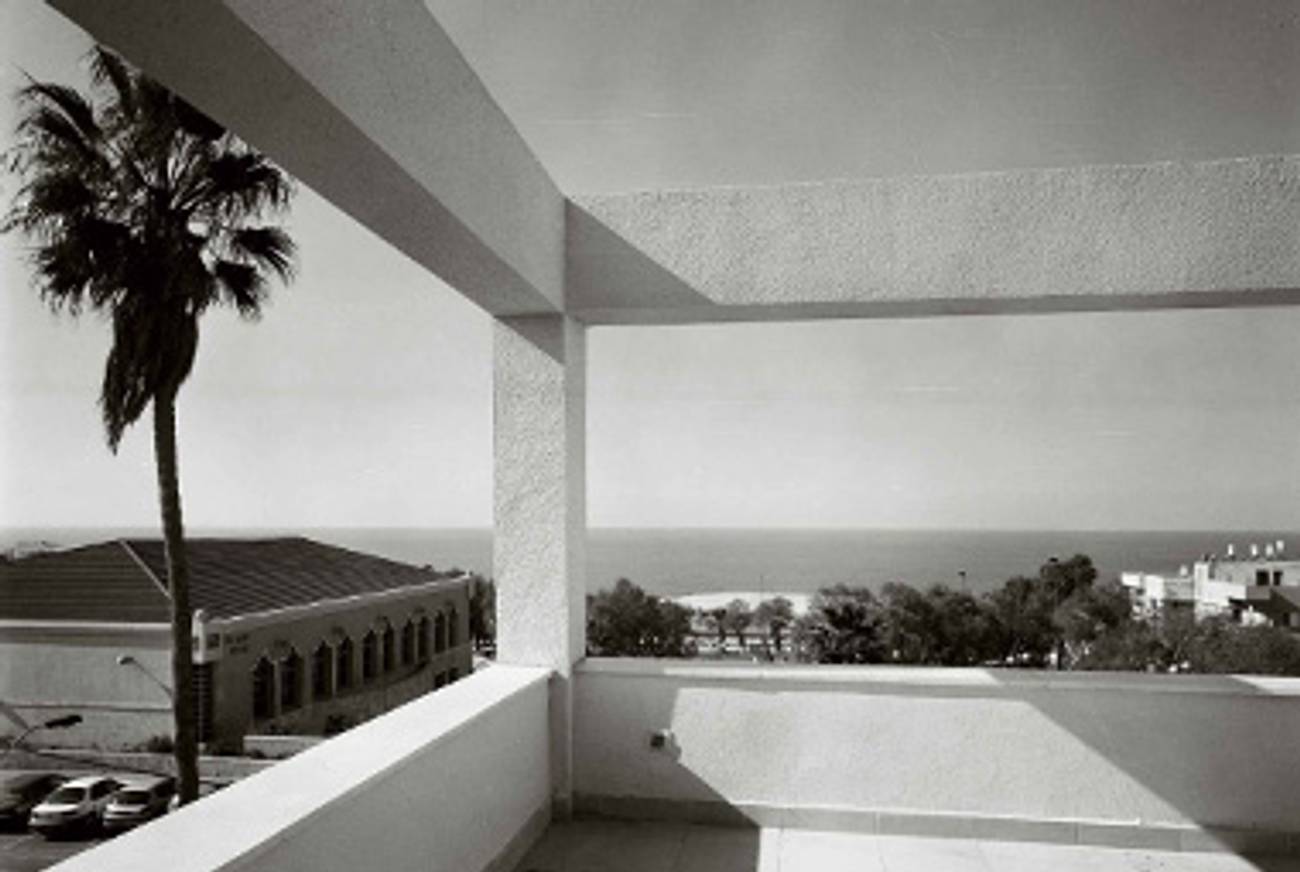

On a high ridge overlooking Israel’s Mediterranean coast stands an elegant, cream-colored villa with a distinctive Modernist design that has long been caught in the crossfire of the Mideast conflict. Its current occupant is Christophe Bigot, the French ambassador to Israel. But the mansion, which is in Jaffa, is the product of an unusual—and eventually ruptured—friendship between a Jewish Zionist architect and his Arab Muslim client.

“We’re passionate about the history of this house,” Valerie Bigot, the ambassador’s wife, told me as a white-jacketed waiter served us coffee on the oleander-filled terrace overlooking the sea. Bigot recently gave me a tour of the house, accompanied by Oded Rapoport, the son of its architect, who told the dramatic tale of how his father and his client together created one of the most fascinating 20th-century dwellings in the Middle East.

The story begins at the Tel Aviv Rotary Club, established in 1934 with a membership one-third British, one-third Arab, and one-third Jewish. There, soon after the club was established, Mohammad Ahmed Abdel Rahim, one of Jaffa’s wealthiest residents, met Yitzhak Rapoport. After seeing an innovative hospital design by Rapoport on a nearby street, Abdel Rahim asked the Ukrainian-born architect to design his new house.

Abdel Rahim owned vast citrus groves and flour mills and was a major exporter of Jaffa oranges. He was open to new technology, and, like the Jews in Tel Aviv, he wanted a forward-looking home with modern amenities. But he also wanted to adhere to his own religious and cultural customs. In response, Rapoport began to devise a minimalist exterior in the spirit of the Bauhaus. The interior was designed with a clear separation of public and private realms, with distinct areas for men, women, and children.

Soon after the ambitious project got under way, it became ensnared in tensions between Arabs and Jews in British-ruled Palestine. But the two men were committed to the project. To ensure his safety during deadly Arab riots in 1936, Rapoport would drive to the neighborhood of Manshiyeh on the outskirts of Jaffa, where he would disguise himself in Arab dress. There, he would be picked up by Abdel Rahim and brought to the construction site. Rapoport would spend the night and work the next day overseeing the execution of his design—all the while being introduced to his client’s other guests as a relative from Kuwait. The following night, Rapoport would return to his regular life in Tel Aviv.

“Abdel Rahim had already broken ranks with his cultural milieu to build a Modernist house,” Oded Rapoport told me later in his office, where he spread out a file of documents relating to his father’s life. “He couldn’t afford to be seen with a Jewish architect.” Let alone one who was—unbeknownst to Abdel Rahim—also a spy.

***

It was an open secret that Abdel Rahim was the treasurer of the Arab group orchestrating the uprising and attacks on Jewish civilian targets in Palestine. What no one knew—or at least no one knew inside the emerging structure in the Ajami area of Jaffa—was that Rapoport was also involved in the fight, as a senior officer of the Jewish paramilitary organization Haganah. During his frequent stays with Abdel Rahim, the architect overheard conversations about planned Arab attacks to protest against Jewish immigration to Palestine, and he would subsequently inform the Haganah about their plans.

The design and realization of the house, meanwhile, kept Abdel Rahim and Rapoport in collaboration, and they remained steadfastly protective of one another—but their histories would continue to intersect in complicated ways. After completing the residential commission, Yitzhak Rapoport went on to design a flour mill for Abdel Rahim and warehouses for his many business interests. During the 1948 war, the flour mill’s tower became a strategic post for Arabs, and Rapoport was in the Jewish military unit that blew it up—using his knowledge of the site to determine exactly how to topple it.

Abdel Rahim was able to enjoy living in his new house for only a decade. He was part of a small group that signed the declaration of Jaffa’s surrender to the Jewish troops, and, during the Israeli War of Independence in 1948, his family fled to Lebanon. According to Oded Rapoport, Abdel Rahim left for Beirut with his family, but a nephew of his, Hasan Hammami, says his uncle stayed alone in the mansion for over a year under house arrest before going into exile.

In any case, before the ceasefire, Abdel Rahim transferred ownership of his property to Rapoport, fearing he would lose all claim and have it expropriated. At first, the architect was incredulous, asking, “Why leave it with me? You have family.” Other Arabs, too, remained in Jaffa.

The wealthy man replied, according to Oded, “I don’t trust any of them. I trust you.” He gave Yitzhak Rapoport a proxy for his entire property, even as the architect became Haganah’s chief engineering officer for the Tel Aviv district. “‘I know the Jews will win the war,’” Abdel Rahim told Rapoport.

At war’s end, the newly established Israeli government attempted to nationalize the property, but Oded Rapoport’s father refused to comply. “This is mine,” he told his fellow Zionists. Oded Rapoport explained: “They tried to convince him to drop it. They said, ‘We need it. We’re a new country.’ My father said, ‘I gave of myself to the country, I fought, I gave what was expected of me as a patriot. But I cannot betray my friend.’ ”

In 1949, the French government purchased the house from Yitzhak Rapoport to serve as the official residence of its ambassador to the fledgling Jewish state. The architect then passed on the money to Abdel Rahim, traveling to Naples in the 1950s to meet with him and complete the transfer. Abdel Rahim died in Lebanon in the early 1960s, and Rapoport gradually lost contact with the family as personal communications between Israelis and Arabs became increasingly suspect.

Arab residents of Jaffa have periodically cast doubt upon the story of whether the property was actually sold, most recently in interviews in a 2006 documentary by filmmaker Gadi Nemet broadcast on Israeli television. French authorities counter that Abdel Rahim appointed Rapoport as his agent, that the Foreign Ministry in Paris bought the four-bedroom house from the architect at full market value, and that he, in turn, gave the proceeds to the original owner. I recently confirmed that a transaction of some kind took place by locating the original bill of sale for 20,000 British pounds at the Tel Aviv municipal land registry office.

Yitzhak Rapoport died in 1989. Oded Rapoport took over his practice and has helped successive French ambassadors carry out minor renovations to the original residence. “Whenever a new ambassador arrives, I get a call,” said the younger Rapoport.

***

By the last odd twist of fate in a story littered with them, Oded Rapoport’s experience with Arab architectural commissions has ended up mirroring that of his father. In 1983, Oded designed a house in Gaza for a Palestinian friend. The project got under way during the First Intifada, and the client would meet Oded every other week at the border crossing between Israel and Gaza and then safely ferry him through barricades to a construction site in a car that flew the flag of the Red Crescent.

The client was Akram Matar, an ophthalmologist who ran an eye clinic in conjunction with Israeli doctors. Matar, a wealthy Muslim who studied in England and Germany, wanted a modern house in the upscale Rimal neighborhood of Gaza City, and in the process of designing the project Oded Rapoport and his wife became good friends with Matar and his wife.

Sometime after the house was finished, and following the Oslo accords, Matar invited Rapoport—a pilot in the Israeli Air Force—to Gaza for a celebration at his home in 1994. “We came to the main gate accompanied by the Palestinian police in a convoy,” Oded recalled. “Suddenly Yasser Arafat came in. It turned out to be a surprise birthday party for Arafat.”

The architect doesn’t know what happened to his design in the 2009 bombardment of Gaza during Israel’s Operation Cast Lead. Matar’s children had become more religious as Islamic fundamentalism gained influence in Gaza in the late 1990s. “Somehow the circle was closed,” Oded said quietly, before explaining that Matar died 10 years ago. “Unfortunately, personal stories are so different from the national story.”

Michael Z. Wise, the author of Capital Dilemma: Germany’s Search for a New Architecture of Democracy, is a contributing editor at Travel + Leisure.

Michael Z. Wise, the author of Capital Dilemma: Germany’s Search for a New Architecture of Democracy, is a contributing editor at Travel + Leisure.