Walter Abish’s first few books gave him a reputation for relentless aesthetic and rhetorical experimentation, leaving many readers unprepared for the emotional devastation embodied in his fiercely conceived 1980 novel, How German Is It, which was awarded the PEN Faulkner and has since been translated into 14 languages. Abish’s memoir, Double Vision, which was published earlier this year, tells two converging stories. One follows the writer-to-be, the only child in a prosperous, assimilated Viennese family. Forced to flee when Walter is six, the Abishes wait out the war in Shanghai, then leave for Israel in 1948. After two years in the Israeli army, Walter, determined to become a writer, settles in Tel Aviv, at first working for the American Library, then in a bookstore. In the other, the writer, who has lived in New York since 1957, tours Germany and Austria to promote How German Is It.

Most of your writing, while profoundly autobiographical in some sense, is not autobiography at all. In fact, your best-known work—How German Is It—is famous for being non-autobiographical: You’d never been to Germany before you wrote it. Why write a self-portrait now?

I began writing it in 1980 during a two-month stay at Yaddo. I had just finished How German Is It and didn’t as yet have another project. I decided to write an autobiographical piece, a self-portrait, but I decided to put it aside. At the initial stage, I think I published short snippets, a mention of China, of my family, maybe Uncle Phoebus. They were little vignettes: the Chinese policemen kicking the dead child back and forth, and my feelings about that and my response. I wanted to deal with the personal and I wasn’t quite sure how to. I wasn’t quite prepared to. And so I worked at it for some time and again put it aside.

In the 90’s I decided finally it was time to pick up the manuscript. By this time I had settled on a structure. I had also spent six months in Berlin. The German Jews who play an important role in the writer-to-be section serve as an ideal counterweight to present-day Germany.

And the title, Double Vision?

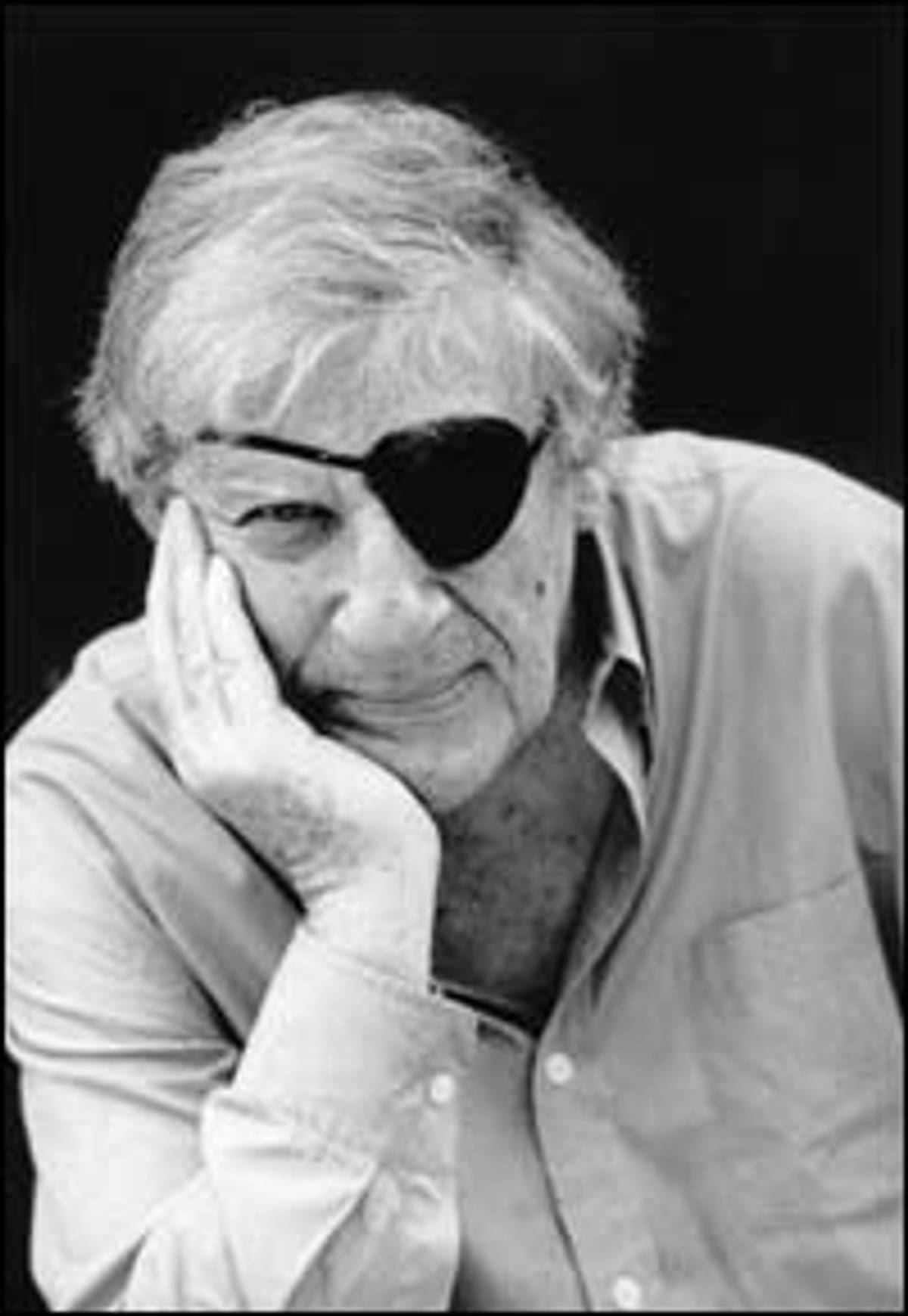

My first book, a collection of poems, is named Duel Site. At the time my wife and I lived near Weehawken and frequently passed the location, identified by the sign DUEL SITE, where Aaron Burr mortally wounded Alexander Hamilton. Obviously, the fact that I have double vision was an added inducement to pick the title.

You didn’t talk about that in the book.

Not at all.

You can’t make it too easy, right?

It’s not a question of making it easy. I would like to engage the reader by withholding the familiar. My work invites interpretation. To provide explanations is to inhibit the reader’s interaction. Often to explain is to explain away.

But isn’t Double Vision a form of explanation?

It’s a book about the making of a writer. I was intrigued—as I still am—by the relationship of the German Jews to Germany and their fellow Germans. Keep in mind that the German Jews were the initial target—I hesitate to use the word victim, since often the ones who embrace victimhood aren’t necessarily victims. For my mother, the obscene graffiti about Jews on the Opera defiled what she most treasured. The German and Austrian Jews must have experienced what occurred as a profound familial betrayal—their next-door neighbors and former friends shunning them, avoiding them. Granted that many German and Austrian Jews deceived themselves about their German and Austrian identity.

At one point in the book, during your first trip to Germany, you’re taking photographs—

You’ll notice that I haven’t included any of my family. I felt that the photos would mislead. I wanted to leave it to the imagination. Incidentally, when How German Is It appeared in Germany the reviewers, not knowing how to react, did what people would do elsewhere. They read me instead. They explained me. No problem there: Vienna, fled the Nazis, they’ve got the whole story—why read the book? And there’s a review in the Houston Chronicle, some professor at the University of St. Thomas, and he writes that I end up in America and that’s a happy ending. People really bring their own history to it. Many books do not invite that.

But for American readers of the new book, it’s more like Experimental Writer Finally Gets Personal. Your books have formal conceits that control, to some degree, the content of the book. Alphabetical Africa, with its first and last chapters made up of words that begin only with A, is the most extreme, but it’s also true of the collage you made in 99: The New Meaning.

99: The New Meaning is deliberate, it’s carefully chosen and arranged. I wanted the idea—my extracting and arranging segments from books by other writers to create a narrative to dominate and color the reading. I deliberately withheld the names of the authors. In general, structure enables me to frame or emphasize the visual. I have to be able to see what I write.

You see all of your writing as—well, probably not seamless, but—

It’s a body of work. Absolutely, absolutely. And Double Vision is to augment that body of work. As well as to provide commentary on it.

I can see that in your mind there might not be much difference between the formal conceit of Double Vision and of 99: The New Meaning. But how does it fit into the scheme? You have the writer-to-be, you have the writer.

The writer is present in almost all my work. In Eclipse Fever, for instance, in the form of the critic—who is a cretin, an apparatchik. Paradoxically, I’m fond of him. The writers are the intermediary. They stand between me and the text.

To people who say to you: you’ve been doing all this stuff—these formal experiments—and here you are writing a very direct book. There’s a sense of that in some of the critics—and John Updike does that in The New Yorker—that you had been cheating them previously and that now you were delivering the goods.

I didn’t get the sense that he was implying that.

Obviously he’s been an admirer—a somewhat unlikely admirer—of yours all along. What I mean is that certainly American readers, gorged on memoirs that are very different from yours, recognize that the methods you’re employing in Double Vision are direct in their own way. They’re vignettes you carved out from hundreds of pages more.

I deleted a number of characters and their history, because it would prove difficult for a reader to absorb so many details. I couldn’t have written Double Vision earlier, in 1980 for instance, because I didn’t possess the insight into what I now describe. And I think if you were to rephrase the question—

Go right ahead.

And link it to How German Is It, it becomes more pertinent. Let me give you a brief account. I left Israel in 1956 for England, where I wrote my first play. I was influenced by Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral. My verse drama was set in China, 1949. All the characters are Chinese. The action takes place in a monastery overlooking the Yangtze, which at that time of year has flooded the village at the foot of the monastery. The principal characters, in addition to the monks who remain undecided on how to respond to Mao’s conquest of China, are three individuals fleeing from Shanghai. One is a bar girl, one is a con man, and a prostitute. I’m sorry, a poet.

I always mix them up, too.

Though I was unaware of it, I’m already at this early stage toying with the familiar and defamiliarization. I’ve never lived in a Chinese village—I may have visited one. I’ve never been to a Chinese Buddhist temple—all this is foreign to me. My next play, The Burning of the Misfit Child, an unfinished play, is set in the Midwest in a town in which everyone is in one way or another connected to the mental institution, the town’s largest employer. People fear it, they fear ending up there. What they most fear are the mentally ill, the unstable, the misfits. It’s my first impression of America.

In the seventies I went to see a film, Ich liebe dich, ich töte dich (“I love you, I kill you”) by Uwe Brandner, an interesting writer living in Munich. A very fascinating, complex, homoerotic film that influenced me to write “The English Garden.” When that story was singled out in The New Yorker and The New York Times, I wrote “The Idea of Switzerland,” which in turn led to How German Is It, in which many of the elements that are important to me are at play.

Since How German Is It came out there have been a number of historical revelations that I want to ask you about. At the time, some Heidegger societies objected to your portrayal of the philosopher Brumhold, whom they nonetheless recognized as the embodiment of their man. How have you felt about the things that have come out about Heidegger?

Delighted. I retain a love-hate relationship to Heidegger. It’s difficult to dismiss the questions he ponders: What is being? What is language? His relationship to Hannah Arendt is revealing. His relationship to Ernst Jünger and to Nazi jurist Carl Schmitt is even more so. He was, I think, politically a naïf; it was Ernst Jünger who influenced Heidegger politically. Jünger was aware of the mass extermination of the Jews. He writes about it in his wartime journals. Though he fails to mention that his farm, to which he retreats at the end of the war, is only a short distance from Bergen-Belsen. In 1942 and ’43 Jünger reads Josephus and Jeremiah contemplating the fate of the Jews, as if it is somehow disembodied. After the war, though he continues to keep a journal, he never mentions the word Jew again. They have literally ceased to exist for him. He stated something to the effect that the Germans who lived abroad—clearly, by that, including the Jews—should not be the ones to judge Germany’s wartime conduct. That should be left to people who experienced the war from within Germany. Heidegger clearly took Jünger’s injunction to heart.

To switch gears for a minute, you talk a lot in Double Vision about Viennese rhetorical and conversational modes of seduction, about the temptation of belonging to a gemütlich culture. Do you think of yourself at all as a Viennese writer, in that sense?

When I came to Vienna, I was received as one. I don’t see myself as one. But I haven’t explored it fully. It became too Freudian almost.

It is Vienna. At one point in the book you imagine what you might have been like if you were a Viennese writer.

It’s true. On my return to Austria I became aware of what I would call a subtle collusion. When you said, “Am I Viennese?”—I could easily pretend to be, and they would pretend, and this could have gone on. This might have continued ad infinitum had not Waldheim become chancellor. Suddenly my seeming collusion became odious.

This is a hard question to ask, but in what sense do you think of the book as a direct, Proustian evocation of this lost world—or found world, however you want to look at it—in terms of your parents? It’s not something people would expect from you.

Well, in the book I refer to Proust. I compare Walter Moses, one of what I call my German fathers in Tel Aviv, to Baron de Charlus. I write of my determination to have Proust as my influence. I think I am being consistent. I can distinguish between a rich literary past and nostalgia. I’m not trying to recapture the past. I’m called experimental. The word carries less and less weight. I see everything I’ve written as somehow connected. I once wrote a paper on the familiar and everyday life and literature. I had certain ideas that proved erroneous. I believed that the familiar was something to be mapped. It’s nothing of the kind. We familiarize the world unless that instinctive need to familiarize is blocked, stunted. I don’t know if that sheds any light on Double Vision.

There were a few things that really struck me about the Mayan scribes, whose complicity in the sacrificial violence that defined their society you describe at the end of your book. One was that you wanted to ensure your book couldn’t be read as a kind of Goldhagen-like criticism of Germans, although people seem to be doing this anyway. Why did you feel this was necessary? I mean, this is a funny question since it’s already happened: Updike responded so personally, started talking about the German line in his family, like you had somehow accused him of participating in some way.

Or of my animus to Germany. Animus to me serves as an energizer—it is not the generator. Why did I introduce the Mayan scribes? Now that scholars have deciphered the script, what scholars took to be tranquil religious communities turn out to have been warring states. The scribes were privileged members of the royalty whose task was to enhance the stature of their king. They created a kind of usable history. They didn’t oppose bloodletting or sacrifice.

Like Jünger?

It was their society, their culture. Look, I feel people are manipulatable and I’m intrigued by how societies devise rules and develop a logic that drives and charges their society. So it seemed appropriate here, to focus on the role of the writer. Furthermore, during the Mayans’ decline, the scribes remained consistent, falsifying history. The scribe’s dilemma must have been, how to oppose, and what risks could he take without having his fingers chopped off? I can identify with them.