Why Zionism Is Americanism

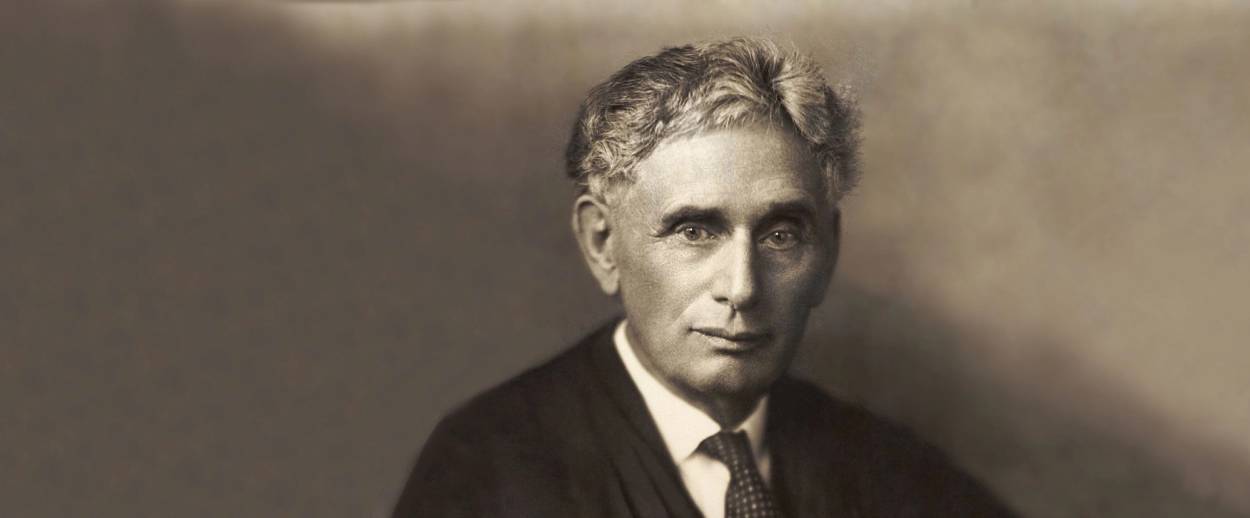

An excerpt from Jeffrey Rosen’s new biography of the Supreme Court Justice Louis D. Brandeis shows the extraordinary jurist thinking about America and Israel

This is a sponsored post on behalf of Yale University Press and their Jewish Lives series.

Louis D. Brandeis’s Jeffersonian ideals about democratic participation and small-scale self-government eventually came to focus on a distant place where he dared to believe that they could be achieved. That place was Palestine. Raised as an unobservant and nonpracticing Jew, Brandeis experienced a remarkable personal and intellectual transformation in his fifties. He became the head of the Zionist movement in America.

How did he become a Zionist? Although he never denied his Judaism, Brandeis had identified only marginally with Jews since his childhood in Louisville, in keeping with the secular tradition of his ancestors. This changed in 1910. “Throughout long years which represent my own life, I have been to a great extent separated from the Jews,” Brandeis declared in 1914 during his remarks at an emergency meeting of American Zionists at the Hotel Marseilles in New York, which he agreed to chair at the request of the young Zionist and cultural critic Horace Kallen. “I am very ignorant in things Jewish.” But he went on to say that “recent experiences, public and professional, have taught me this: I find Jews possessed of those very qualities which we of the twentieth century seek to develop in our struggle for justice and democracy; a deep moral feeling which makes them capable of noble acts; a deep sense of the brotherhood of man; and a high intelligence, the fruit of three thousand years of civilization.” All of these experiences convinced Brandeis “that the Jewish People should be preserved.”

What were the “public and professional” experiences that transformed Brandeis’s outlook from indifference about Judaism to crusading Zionism? By his own account, he had come to Zionism through Americanism. Before 1910, Brandeis, like many upper-class American Jews of central European heritage, was skeptical of Zionism because of his concerns about “dual loyalties” and his support for melting-pot assimilationism. His first public comments about Judaism can be found in 1905, in a speech commemorating the 250th anniversary of Jewish settlement in America at the New Century Club in New York. In the speech, “What Loyalty Demands,” Brandeis echoed Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson in warning of the dangers of separatism. “In a country whose constitution prohibits discrimination on account of race or creed, there is no place for what President Roosevelt has called hyphenated Americans,” Brandeis declared. “Habits of living or of thought which tend to keep alive difference of origin or to classify men according to their religious beliefs are inconsistent with the American ideal of brotherhood, and are disloyal.”

In the fall of 1910, Brandeis first met Jacob de Haas, the editor of the Jewish Advocate in Boston, who had been summoned with other local reporters by the public relations agent of the Savings Bank Insurance campaign. De Haas was the American secretary of Theodor Herzl, whose 1896 book Der Judenstaat had proclaimed the Jewish people’s need for a state of their own. He had come to America as Herzl’s representative to convene the First Zionist Congress in Chicago the following year; after immigrating to America in 1902, he eventually moved to Boston. De Haas was initially ambivalent about the press roundup for Savings Bank Insurance—“the theme seemed both dry and remote,” as he put it later in his biography of Brandeis—but the interview was a success. After his interview with de Haas, Brandeis made his first recorded statement on Zionism: “I have a great deal of sympathy for the movement and am deeply interested in the outcome of the propaganda,” Brandeis declared in the Advocate. “I believe that the Jews can be just as much of a priest people today as they ever were in prophetic days.”

Brandeis was especially receptive to Zionism in 1910, having been moved by his experience working with eastern European Jews on both sides of a cloak makers’ strike in New York earlier that year. During the negotiations, both the Jewish garment workers and their Jewish employers impressed him—with their intellectualism, idealism, and commitment to industrial democracy as well as their accounts of the anti-Semitism that had led them to emigrate from eastern Europe. The dispute was over the “closed shop”—whether nonunion workers could apply for jobs—and Brandeis brought the two sides together around the idea of the “preferential union shop,” whereby union members would be favored but nonmembers could apply. The strike was Brandeis’s first real contact with eastern European Jews, and he was deeply impressed by their ethical attitude and capacity for idealism and empathy. “What struck me most was that each side had a great capacity for placing themselves in the other fellows’ shoes,” Brandeis told de Haas. “They argued, but they were willing to listen to argument. That set these people apart in my experience in labor disputes.” Identifying with the earnest garment workers, Brandeis relaxed after an arduous day of negotiations by indulging in a glass of beer with them and telling them war stories about the Pinchot-Ballinger affair. For the first time, at the age of fifty-four, he had gained faith in the Jewish immigrant masses and become conscious of his own Jewishness. Still, Felix Frankfurter noted, Brandeis would require “long brooding” before he could commit himself to Zionism.

A second meeting with Jacob de Haas in August 1912 accelerated Brandeis’s embrace of the Zionist cause. De Haas visited Brandeis in South Yarmouth at his summer house. (Brandeis always left the city for the month of August, writing, “I soon learned that I could do twelve months’ work in eleven months, but not in twelve.”) De Haas had come to talk about fundraising for Woodrow Wilson, but on the way to the train station after the interview, he asked whether Brandeis was related to Lewis Dembitz. When Brandeis said yes—he had changed his middle name to Dembitz to honor his revered uncle—de Haas replied twice that “Lewis N. Dembitz was a noble Jew,” because he had been one of the first American supporters of Theodor Herzl’s plans to establish a Jewish homeland. Brandeis was pleased and intrigued by this tribute and promptly invited de Haas back to his cottage for lunch. There he learned that Dembitz, whom Brandeis had known as an abolitionist, a delegate to the Republican convention of 1860, and the only observant Jew in his extended family, was a committed Zionist. He urged de Haas to educate him about Theodor Herzl and the Zionist movement and began a rigorous program of selfstudy. As de Haas put it, “[F]rom that first interview he began an earnest quest for knowledge. … He studied the footnotes as well as the printed page of Jewish history and made the Zionist idea his own.” Brandeis later told Felix Frankfurter that de Haas had kindled his interest in Zionism and declared de Haas to be “the maker of American Zionism.”

In fact, Brandeis became the maker of American Zionism. But he assumed that role only after meeting another Zionist and reading several life-changing books. The Zionist was Aaron Aaronsohn, the head of the Jewish Agricultural Experiment Station in Palestine, known as “the pioneer of scientific agriculture” for his discovery of “wild wheat.” Brandeis met Aaronsohn after hearing him lecture on agriculture in Chicago in 1912. The lecture hit its mark, as did the conversation afterward. In a speech called “To Be a Jew” delivered the following year, Brandeis, who was not known to gush, described Aaronsohn as “one of the most interesting, brilliant and remarkable men I have ever met … [who] made what is considered one of the most remarkable and useful discoveries in recent years, and possibly of all times.” Brandeis’s Jeffersonian agrarianism was drawn to Aaronsohn’s discovery of “wild wheat,” which Brandeis thought could “immeasurably increase” the quantity of food available across the globe because wheat could now be cultivated in soil previously considered too arid. His sense of the Jews as a uniquely ethical people was kindled by Aaronsohn’s report that “not a single crime was known to have been committed by one of our people” in Palestine during the past thirty years. When Brandeis asked him why, he replied: “Every member of those communities is brought up to realize his obligation to his people. He is told of the great difficulties it passed through, and of the long years of martyrdom it experienced. All that is best in Jewish history is made to live in him, and by this means he is imbued with a high sense of honor and responsibility for the whole people.”

Although Aaronsohn was strongly opposed to socialism, Brandeis was thrilled to learn from him that Jews were applying the principles he valued most—scientific agriculture and self-governing, small-scale democracy—in Palestine. As David Riesman wrote to me years later, “Brandeis was … a Zionist, in contrast to the assimilated German Jews (He belonged to a sect even more assimilationist than Americanized German Jews in general). This is because he saw Palestine as rural, made up of cooperatives rooted in the land, which he interpreted as not very different from the feeling of dedicated Southerners toward the land.” After hearing Aaronsohn’s talk, Brandeis gave his first speech supporting Zionism to the Young Men’s Hebrew Association in Chelsea. “We should all support the Zionist movement, although you or I do not think of settling in Palestine, for there has developed and can develop in that land to a higher degree, the spirit of which Mr. Aaronsohn speaks.” Brandeis’s idea—that American Jews had a duty to support Palestine but no obligation to move to Palestine—was, for the Zionist movement, an intellectual breakthrough.

Fired up by the example of de Haas and Aaronsohn, Brandeis began a program of systematic reading on Zionism, starting with the work of Horace Kallen, the leading American theorist of cultural pluralism, who was also one of the first American Zionists. Brandeis had first met Kallen when the younger man was a Harvard undergraduate at the turn of the century, a time when teachers such as William James were convincing Kallen of the influence of the Hebrew Bible on the Puritan mind and the American founding fathers. These Yankee intellectuals led Kallen from Cotton Mather to Jefferson to Zionism; he concluded that Zionism would extend the Jeffersonian values of liberty and equality to all members of a self-governing Jewish state. Far from being inconsistent with American ideals, he concluded, American support for Zionism could help to spread them across the globe. In 1913, Kallen sent Brandeis an essay he had written, “Judaism, Hebraism, Zionism.” In this essay, Kallen introduced an idea that Brandeis would later develop: that preserving a distinct Jewish identity in Palestine was the best way to preserve a unique Hebraic culture that could enrich both America and the world. As Kallen recalled of Brandeis much later, in a 1972 interview, “The important thing for him was that the proclaimed antagonism between Americanism and Zionist was a false claim—it didn’t have to be. … Because to begin with he believed that he could not be an American and a Zionist completely. Then he came to believe that he could, and that he would, and he did.”

Kallen rejected the assimilationist ideology in “Democracy versus the Melting Pot,” a 1915 essay in the Nation that he later incorporated into his book Cultural Pluralism. He wrote that members of immigrant groups could not, and should not, try to shed their unique cultures and values, since by retaining their hyphenated identities and personalities they could better contribute to the diversity of the American whole. Kallen concluded that preserving group differences was the best way of achieving the Jeffersonian equality promised in the Declaration of Independence. “As in an orchestra,” he wrote, “every type of instrument has its specific timbre and tonality. … [A]s every type has its appropriate theme and melody in the whole symphony, so in society, each ethnic group is the natural instrument … and the harmony and dissonances and discords of them all may make the symphony of civilization.” Kallen also insisted that Jewish immigrants, as they became free Americans, tended to become more Jewish, not less. “The most eagerly American of the immigrant groups are also the most autonomous and self-conscious in spirit and culture.” This insight helped Brandeis to reconcile two ideals—Zionism and Americanism—that he had previously found to be in conflict. For American Jews to support a Jewish homeland, he now concluded, would create better Americans and better Jews at the same time.

In addition to helping Brandeis to solve the problem of dual loyalty, Kallen also helped to connect Brandeis to yet another intellectual influence who proved to be decisive in his thinking about Zionism: Alfred Zimmern. An Oxford classicist and active Zionist, Zimmern had recently published The Greek Commonwealth (1912), which Brandeis read during the winter of 1913–14. Brandeis later recalled it was his only recreation during the New Haven Railroad investigation and that it pleased him more than anything he had read, except for Gilbert Murray’s translation of The Bacchae. The book helped Brandeis unite his interests in ancient Greece, Jeffersonian democracy, and Zionism, and he recommended it to everyone he encountered—from law clerks to family and friends—for the rest of his life. Like Zimmern, Brandeis came to see the Jewish return to Palestine as a fulfillment of the democratic ideals he admired in fifth-century Athens.

The similarities between Brandeis’s and Zimmern’s vision of the possibility of democracy in Palestine and Greece are striking. As Philippa Strum has noted, Zimmern believed that geography and economic conditions were a central determinant of culture, and that Palestine’s geography, like that of Athens, made it ripe for a democratic society. By juxtaposing Jewish sources—from the Old Testament, the prophets, and Jewish history—alongside Greek sources, Zimmern suggested that classical civilizations of both cultures shared many of the same values. With Zimmern’s guidance, Brandeis came to view Palestine as a society that could achieve the kind of small-scale Jeffersonian agrarian democracy that had reached its fullest expression in fifth-century Athens and that allowed men and women to develop their faculties of reason and self-government on a human scale.

Reading The Greek Commonwealth today, one can imagine Brandeis nodding with appreciation and intellectual excitement as he found his ideas about the importance of geography and economics for democratic self-government illustrated and confirmed on page after page. Zimmern’s discussion “Politics and the Development of Citizenship” begins with this epigraph: “They spend their bodies, as mere external tools, in the City’s service, and count their minds as most truly their own when employed on her behalf.” Brandeis embraced, as we saw in the introduction, Zimmern’s definition of leisure as time spent away from work on creative and intellectual pursuits that made personal and political self-government possible. And Brandeis found in Zimmern’s account of Periclean Athens other axioms that reinforced his Jeffersonian belief that self-government on a human scale could be realized in Palestine.

Zimmern’s chapter “Self-Government, or the Rule of the People,” for example, stressed the duty of political participation and small-scale deliberation: “Democracy is meaningless unless it involves the serious and steady co-operation of large numbers of citizens in the actual work of government.” Compare Brandeis on banker management: “[N]o man can serve two masters” and “[A] man cannot at the same time do many things well.”

In his chapter “Happiness, or the Rule of Love,” Zimmern notes that “the extraordinary resemblance between Lincoln’s speech at Gettysburg and Pericles’s has often been noticed.” He then translates the funeral oration in words that clearly moved Brandeis in composing his Whitney concurrence, emphasizing that only by avoiding gossip and focusing on matters of public concern can citizens be fully engaged in public deliberation: “Our constitution is named a democracy, because it is in the hands not of the few but of the many. But our laws secure equal justice for all in their private disputes, and our public opinion welcomes and honors talent in every branch of achievement, not for any sectional reason but on grounds of excellence alone. And as we give free play to all in our public life, so we carry the same spirit into our daily relations with one another. We have no black looks or angry words for our neighbor if he enjoys himself in his own way.”

Up until this point, Brandeis could, and did, translate Zimmern’s vision of Periclean Athens into his own vision of Jeffersonian America. “What are the American ideals?” Brandeis asked in “True Americanism.” “They are the development of the individual for his own and the common good; the development of the individual through liberty, and the attainment of the common good through democracy and social justice.” But there were aspects of Jefferson’s agrarian America that could never be recovered in Wilson’s industrial America. Brandeis was especially struck, therefore, by Zimmern’s discussion of Greek geography, craftsmanship, and cooperative ownership, which he yearned to re-create in the wilderness of rural Palestine.

In Periclean Athens, the craftsman “lived in close touch with the public for whom he performed services, not separated, like the modern workman, by a host of distributors and intermediaries. It was on the direct appreciation of the citizens that he depended for a livelihood.” Brandeis would later attribute the spirit of the craftsman to “the educated Jew,” quoting Carlyle for the proposition that the two most honored men were “the toil-worn craftsman who conquers the earth and him who is seen toiling for the spiritually indispensable.” And Brandeis arranged his own personal and professional life to fulfill the ideal of the craftsman that the Athenians perfected.

Zimmern concludes The Greek Commonwealth in the first years of the Peloponnesian War, as Pericles is deposed as general and then dies in disappointment because he has forgotten his own warnings about the curse of bigness and the dangers of imperial overreach. “Thus it was that, by one of Fate’s cruelest ironies, Pericles, the cautious and clear-sighted, the champion of the Free Sea and Free Intercourse, who had been warning Athens for a whole generation against the dangers of aggrandizement, was the first to preach to her the fatal doctrine of Universal Sea-power.” And Zimmern ends with a romantic paean to the ideal civilization that has been lost: “For a whole wonderful half-century, the richest and happiest period in the recorded history of any single community, Politics and Morality, the deepest and strongest forces of national and of individual life, had moved forward hand in hand towards a common ideal, the perfect citizen in the perfect state.”

Brandeis resolved to re-create “the perfect citizen in the perfect state” in Palestine. And having made up his mind, he acted swiftly and dramatically. With the outbreak of World War I in Europe, the World Zionist Organization (WZO), headquartered in Berlin, was paralyzed due to its isolation. In response to this need, a group of American Zionists called an emergency meeting at the Hotel Marseilles in New York City on August 30, 1914. As the conference approached, de Haas wrote to Brandeis and asked him “to take charge of practically the whole Zionist Movement.” Acknowledging that he was asking a lot, de Haas added, “I think the Jews of America will accept your leadership in this crisis. … It is not too much to say that everything depends on American Jewry and that Jewry has to be led right.” Brandeis agreed to be nominated, and on the overnight boat trip from Boston to New York, he and Horace Kallen discussed Kallen’s ideas of how Zionism and Americanism could reinforce rather than threaten each other. At the meeting, Brandeis was unanimously elected chair of the dauntingly named Provisional Executive Committee for General Zionist Affairs. His response in accepting the chairmanship of the American Zionist movement was appropriately modest, and it distilled the evolution in his thinking over the past four years about the unique qualities of the Jewish people. “Recent experiences,” he said, “have made me feel that the Jewish people have something which should be saved for the world; that the Jewish people should be preserved, and that it is our duty to pursue that method of saving which most promises success.” After this experience, Brandeis resolved to master Zionism with the same intensity that he focused on every other cause of his life, from Savings Bank Insurance to gas regulation. He wrote a torrent of letters to Zionist organizers and committees demanding regular reports, data, communications, and, as he called it, “propaganda.” “Organize, Organize, Organize, until every Jew in America must stand up and be counted, counted with us, or prove himself, wittingly or unwittingly, of the few who are against their own people,” he exhorted. He devoted part of every day between 191 and his appointment to the Supreme Court two years later to Zionist affairs, installing a time clock in the Zionist offices and irking volunteers as well as staff of the Provisional Executive Committee with his quiet but relentless demands for facts, efficiency, and results. With a high faith in the intelligence of the Jewish people, his goal was to create a democratic movement that would appeal to masses of Jews by reason rather than demagoguery. And the results of his organizing were striking. When Brandeis took over the Zionist movement in August 1914, the Federation of American Zionists had 12,000 members. Five years later, in September 1919, the number had swelled to more than 176,000. The dramatic rise of Zionism in the United States and across the world reflected the fact that the British had conquered Palestine and published the Balfour Declaration; in the United States, however, Brandeis’s organizational abilities, honed by his work as a reformer, helped him to rationalize the finances of the American Zionist movement and to transform it into a powerful influence in American Jewish life and politics. Brandeis was also a prodigious fund-raiser: during the same five-year period, the budget of the movement increased from a few thousand dollars to nearly two million. His motto: “Members, Money, Discipline!”

To mobilize recruits and raise money, Brandeis had to create an intellectual argument for Zionism that overcame the claim that the movement encouraged a divided loyalty for American Jews. This was especially important at a time when Jews were divided over the wisdom of Zionism. Anti-Zionists, led by Reform Jews in the 1890s, opposed the establishment of a Jewish state. “Non-Zionists,” represented by the American Jewish Committee and led by central European émigrés such as Louis Marshall, raised money for European Zionist groups to aid the victims of European anti-Semitism but were ambivalent about a Jewish homeland because of their concerns about hyphenated Americanism. Zionists, led by Reform Jews such as Stephen Wise and including Orthodox immigrants from eastern Europe, were often Progressives, supporters of Woodrow Wilson, and backers of a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

The ambivalence of the non-Zionists and anti-Zionists also reflected fears that the U.S. Congress would limit immigration for disfavored groups. By 1915, there were strong laws and movements to limit immigration from eastern and southern Europe, Asia, and the Middle East. Charges of dual loyalty could have led to a backlash against Jewish immigrants. Brandeis, who was especially drawn to the idea of loyalty, neatly solved the problem of dual loyalty by concluding that American Jews could support Palestine without moving there, acting as loyal Zionists and loyal Americans at the same time.

As early as the fall of 1914, Brandeis saw the consonance of Zionism and Americanism and approached President Wilson, who said he fully sympathized with Brandeis’s Zionist views. For the next several months, Brandeis traveled across America giving speeches to mobilize American Jews and convince them of their wartime responsibilities. In all these speeches, he described his own conversion to the Zionist cause, explaining, “My approach to Zionism was through Americanism.” As he put it, “In time, practical experience and observation convinced me that Jews were by reason of their traditions and their character peculiarly fitted for the attainment of American ideals.” He endorsed Ben Yehudah’s crusade to resurrect Hebrew as the national language of the new Jewish state, emphasizing “that it is through the national language, expressing the people’s soul, that the national spirit is aroused, and the national power restored.” He praised the forty “self-governing colonies” of Palestine for their small scale—“from a few families to some 2,000”—as communities where “the Jews have pure democracy” that gave “women equal rights with men.”

Brandeis issued a series of statements in 1915 exploring the connection between Judaism and Americanism. Along with Felix Frankfurter, Julian Mack, Stephen Wise, and his friend Henrietta Szold, the founder of Hadassah, Brandeis joined the editorial board of the Menorah Journal, founded by the Intercollegiate Menorah Association as an “unqualifiedly non-partisan forum for the discussion of Jewish problems.” In his introduction to the first issue, published in January 1915, Brandeis offered the following reflections on the connections between Jewish and American law and history, which he said shared a commitment to reason and social justice:

To America the contribution of the Jews can be peculiarly large. America’s fundamental law seeks to make real the brotherhood of man. That brotherhood became the Jews’ fundamental law more than twenty-five hundred years ago. America’s twentieth century demand is for social justice that has been the Jews’ striving ages-long. Their religion and their afflictions have prepared them for effective democracy. Persecution made the Jews’ law of brotherhood self-enforcing. It taught them the seriousness of life; it broadened their sympathies; it deepened the passion for righteousness; it trained them in patient endurance, in persistence, in self-control, and in self-sacrifice. Furthermore, the widespread study of Jewish law developed the intellect, and made them less subject to preconceptions and more open to reason.

Brandeis also included in the issue “A Call to the Educated Jew,” which he later delivered as a speech at a conference of the Intercollegiate Menorah Association. Referring to scandals of the day such as the revelation of Jewish prostitution and the 1912 murder of Herman Rosenthal, a casino operator, by Jewish gangsters, Brandeis stressed that Jews should consider themselves “our brothers’ keepers, exacting even from the lowliest the avoidance of things dishonorable,” because of the inevitable public prejudice stoked by Jewish lawbreakers. But he then went further and stressed that the Jewish inheritance of “ideals of democracy and of social justice” imposed duties on all Jews to lead individual lives worthy of their great inheritance while also respecting the rights of others. Brandeis emphasized the singular “Jewish qualities … developed by three thousand years of civilization, and nearly two thousand years of persecution.” They included “intellectual capacity,” “an appreciation of the value of education,” “indomitable will,” and “capacity for hard work.” They also included qualities that Brandeis called “essential to successful democracy: First: an all-pervading sense of duty in the citizen” (similar to that cultivated among New England Puritans, who were “trained in implicit obedience to stern duty by constant duty of the Prophets”); “Second: Relatively high intellectual attainments”; “Third: Submission to leadership as distinguished from authority”; and “Fourth: A developed community sense.” As World War I raged in Europe, Brandeis called on Jews at Columbia University in May 1915 to “make common cause with the small nations of the world,” supporting every people trying to express its national instinct.

The previous month, Brandeis had delivered his most comprehensive statement on Zionism in “The Jewish Problem—How to Solve It,” a speech to the Conference of Eastern Council of Reform Rabbis in New York. He defined “the Jewish Problem” as posing two questions: “How can we secure for Jews, wherever they may live, the same rights and opportunities enjoyed by non-Jews? How can we secure for the world the full contribution which Jews can make, if unhampered by artificial limitations” imposed by anti-Semitism? He argued passionately that hyphenated group identity was important for the development not only of American ideals but also of individual self-fulfillment. “This right of development on the part of the group is essential to the full enjoyment of rights by the individual,” he declared. “For the individual is dependent for his development (and his happiness) in large part upon the development of the group of which he forms a part.” All this was distinctly in the spirit of Zimmern, and anticipated his Whitney concurrence. “We recognize,” he continued, “that with each child the aim of education should be to develop his own individuality, not to make him an imitator, not to assimilate him to others. Shall we fail to recognize this truth when applied to whole peoples? And what people in the world has shown greater individuality than the Jews?” “Of all the peoples in the world,” said Brandeis, “the Greeks and the Jews” are “preeminent as contributors to our present civilization.”

Drawing on Kallen’s ideas of cultural pluralism, Brandeis distinguished between a “nation” and a “nationality.” He declared, “[T]he difference between a nation and a nationality is clear; but it is not always observed. Likeness between members is the essence of nationality; but the members of a nation may be very different. A nation may be composed of many nationalities, as some of the most successful nations are.” The Jews, like the Greeks and the Irish, for example, shared “a community of sentiments, experiences and qualities” that made them a nationality, whether the Jews admitted it or not. Denouncing the ancient notion that the development of one people involved domination over another, Brandeis rejected the “false doctrine that nation and nationality must be made co-extensive.” This had led to tragedies caused by “Panistic movements,” used by Germany and Russia, as a “cloak for their territorial ambitions”; it also had led to the rise of anti-Semitism in Germany. Instead, Brandeis proposed “recognition of the equal rights of each nationality,” and he insisted that the Jews deserved the same right as every other nationality, or “distinct people,” in the world: “To live at their option either in the land of their fathers or in some other country; a right which members of small nations as well as of large, which Irish, Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian, or Belgian, may now exercise as fully as Germans or English.”

In his call for “recognition of the equal rights of each nationality,” Brandeis found in Zionism his own best answer to “the Jewish Problem.” He wrote that “Zionism seeks to establish in Palestine, for such Jews as choose to go and remain there, and for their descendants, a legally secured home, where they may live together and lead a Jewish life, where they may expect ultimately to constitute a majority of the population, and may look forward to what we should call home rule.” And he envisioned mutual benefits for Palestine and for America, as Zionism warded off assimilationist tendencies among American Jews who decided to support the Jewish homeland but not settle there, preserving the individuality of the American Jewish community. By “securing for those Jews who wish to settle there the opportunity to do so, not only those Jews, but all other Jews will be benefited, and … the long perplexing Jewish Problem will, at last, find solution.”

Now convinced of the value of group differences for preserving American ideals, Brandeis responded to what was his own previous antihyphenation position: “Let no American imagine that Zionism is inconsistent with Patriotism. Multiple loyalties are objectionable only if they are inconsistent. A man is a better citizen of the United States for being also a loyal citizen of his state, and of his city; for being loyal to his family, and to his profession or trade; for being loyal to his college or his lodge. Every Irish American who contributed towards advancing home rule was a better man and a better American for the sacrifice he made. Every American Jew who aids in advancing the Jewish settlement in Palestine, though he feels that neither he nor his descendants will ever live there, will likewise be a better man and a better American for doing so.”

Far from causing a clash of identities, he concluded memorably, “there is no inconsistency between loyalty to America and loyalty to Jewry” because both American and Jewish fundamental law seek social justice and the brotherhood of man. On the contrary, “loyalty to America demands rather that each American Jew become a Zionist.”

Brandeis argued, in short, that the Zionist ideals of democracy, individual liberty, freedom of religion, and progressive social values were entirely American and that, in fact, our “Jewish Pilgrim Fathers” would export Jeffersonian values to Palestine. He envisioned Palestine as a secular, liberal democracy ruled by ethical values of equality and social justice, and not by Jewish law. Although Jews would constitute a majority, in his vision, they would respect the equal political and civil rights of all inhabitants, including Arabs.

***

Brandeis’s efforts throughout the 1930s to maintain the British commitment to a Jewish Palestine—one that he hoped would include Transjordan—were accelerated as anti-Semitism swept across Europe and the Nazi menace grew. As Hitler took power in 1933, Brandeis advised Stephen Wise, the head of the American Jewish Congress, to organize a mass protest against German anti-Semitism that drew more than twenty thousand people to Madison Square Garden. “The Jews must leave Germany!” Brandeis told Wise. “The day must come when Germany shall be Judenfrei and Germany shall see for itself how to live without its Jewish population.” Alas, too many of them stayed where they were. Brandeis died in 1941, and so he never learned the worst.

Between 1933 and 1939, three hundred thousand Jews emigrated from Germany. Sixty-two thousand went to the United States and fifty-five thousand to Palestine. (Brandeis’s second cousins from Vienna were among those émigrés who escaped the Holocaust.) But the British continued to limit immigration to Palestine at the same time that the grand mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin al-Husseini, whom the British had appointed in 1921, was engineering the bloody riots of 1929 and 1936, calling on Arabs to attack the Jews. (The grand mufti eventually fled to Germany in 1941, where he met with Hitler in the Reich Chancellery and called on him to exterminate Jews throughout the Middle East. A photograph of the meeting suggests that Hitler welcomed the suggestion.) Brandeis was appalled by the riots of 1936 and by the British reaction. As his law clerk David Riesman wrote to me years later: “An unforgettable occasion, giving a sense of Brandeis’s fierceness, was when Harold Laski came to see him, an old friend. All this was in the 1935–36 term of the court. Brandeis said to Laski that he hoped that the British and the Germans would fight and destroy one another! Laski was horrified. Brandeis had not only the Nazis in mind, but also his antagonism to the British control of Palestine and the widely shared view of Americans about Britain as a colonial power.”

The British responded to the riots of 1936 with the Peel report of 1937, which recommended the restriction of any further Jewish immigration and the partition of Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem and Bethlehem as neutral zones under British supervision. The Arabs immediately convened a summit and condemned the proposal, but Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion both supported partition as the only viable solution. Brandeis, however, strongly opposed partition on the agrarian grounds that economic development in Palestine would be impossible unless the Jews had sufficient arable land. Instructing his acolytes to “stand firm against partition” as a “stupid, ignoble action,” Brandeis summoned Ben-Gurion to his summer house in Chatham, on Cape Cod, to denounce the proposal. Although the World Zionist Congress voted to explore the possibility of partition, the British abandoned the idea at the end of 1938 in the face of Arab opposition.

In October 1938, Brandeis went to the White House to discuss the Palestinian question with President Roosevelt. During the meeting, he advocated the immigration of the Arab population in Palestine to Transjordan or Iraq. (This position was based on his belief that there was an influx of Arabs into Palestine, including Bedouins, who could be returned to their lands of origin.) As Brandeis wrote to Frankfurter, “F.D. went very far, in our talk, in his appreciation of the significance of Palestine, the need of keeping it whole and of making it Jewish. He was tremendously interested, and wholly surprised, on learning of the great increase in Arab population since the war, and on hearing of the plenitude of land for Arabs in Arab countries, about which he made specific enquiries.” Roosevelt floated the proposal to the British but later wrote to Brandeis that British officials didn’t agree that “there is a difference between the Arab population which was in Palestine prior to 1920 and the new Arab population.” As an American who lived in an age of immigration—in his lifetime, millions of Italians, Jews, and Poles came to the United States—Brandeis welcomed the idea of transnational migration. With progressive logic, he believe that since the Arab nationalities had many homelands, the Jewish nationality needed at least one.

What is the pertinence to our contemporary vexations of Brandeis’s vision of Zionism and hyphenated identity? In his idealization of small-scale agrarian democracy in Palestine as the culmination of Jeffersonian shires and the Athenian polis, Brandeis was, of course, something of an idealist. He envisioned a Jewish state that was democratic, secular, and cooperatively owned, a country whose economic success would be shared and embraced by the Arab minorities whose equal civil and political rights it would scrupulously respect. In this sense, he resembled Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir and the first two generations of idealistic Zionists after the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. (Brandeis greatly admired Ben-Gurion, whom he considered the representative of the new generation of Zionist leaders, and when Ben-Gurion said that Jews had to be able to defend themselves, Brandeis gave money—laundered through Stephen Wise and Robert Szold—that allowed the Yishuv—the Jewish residents of Palestine—to buy arms.) But the Jewish state did not develop in a communalist direction; it thrived economically as a bastion of democratic capitalism. With his single-minded focus on economic development fired by individual effort and the economic self-sufficiency of small enterprises, however, Brandeis would surely have approved of Israel’s economic miracle as a “start-up nation”: thanks to the technology that has been responsible for 95 percent of Israel’s economic productivity, the country has produced more startup companies than the United Kingdom, Japan, India, Korea, and Canada. His favorite Palestinian enterprise in the 1930s was a loan bank that the Palestine Economic Corporation used for small loans to small businesses, including farmers and artisans; he viewed it as a model for “small loans” legislation in the U.S. Congress and state legislatures. Brandeis’s idealistic vision never appealed to those immigrant Jews who were far more religiously and culturally Jewish than Brandeis and wanted a movement and a Jewish state that would be sectarian, ideological, and nationalistic rather than progressive, secular, and democratic. This charged division about the definition of the Jewish state continues to this day. As a progressive and a rationalist, Brandeis believed that once religious Jews were exposed to economic facts, they, too, would become progressive and rationalist. He did not anticipate, and would not have understood, the rise of Jewish fundamentalism that threatens Israel’s secular identity. And Brandeis’s other blind spot was his failure to anticipate or to understand Arab nationalism. His purely economic analysis of Jewish migration to Palestine assumed that a rising tide would lift all boats: through communal effort, swamps would be drained, the previously arid land would flow with milk and honey, and malaria would be eliminated for Jews and Arabs alike. In fact, Palestine’s early economic success did indeed attract Arab migration as Brandeis had hoped: between 1922, the beginning of the British mandate, and 1948, the Arab population doubled from over six hundred thousand Muslim and Christian Arabs to over 1.2 million, and the Jewish population grew to over six hundred thousand. (These numbers reflected the draconian immigration quotas for Jews imposed by the British in the 1930s.) The standard of living for both Arabs and Jews grew more rapidly than in neighboring lands. But Brandeis failed to anticipate the anti-Semitic eliminationism of the grand mufti—which is why he was surprised by the massacre of 1929 and tried to blame it on absentee landlords and Bedouins.

Excerpted from Louis D. Brandeis: American Prophet, by Jeffrey Rosen. Copyright © 2016 by Jeffrey Rosen. Excerpted by permission of Yale University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

***

Jeffrey Rosen is President and CEO of the National Constitution Center, professor of law at George Washington University Law School, and a contributing editor of the Atlantic.