The Wolf of Baghdad

A new graphic novel about the Iraqi Jewish experience

The Wolf of Baghdad: Memoir of a Lost Homeland, a new graphic novel about the Iraqi Jewish experience, is testament to the power that Iraqi roots can still possess across a seemingly definitive distance.

Carol Isaacs, author of this skilful and saddening book, is a cartoonist known for her work in The New Yorker as The Surreal McCoy, and an accomplished musician. She was born to Iraqi Jewish parents in London. Her family home was in Wembley, an area of northwest London with a Jewish population of various backgrounds. It would transform into a vessel of life from the old country when visitors came on Sunday. Her parents and grandparents spoke Judeo-Arabic. But talk of life in Iraq, and the shock of her family’s expulsion from it, was mostly absent. At her “very British” school, Jews were a minority and Isaacs a Mizrahi minority within that minority, but she learned from her Ashkenazi friends that European Jews had also experienced expulsion and dispersal.

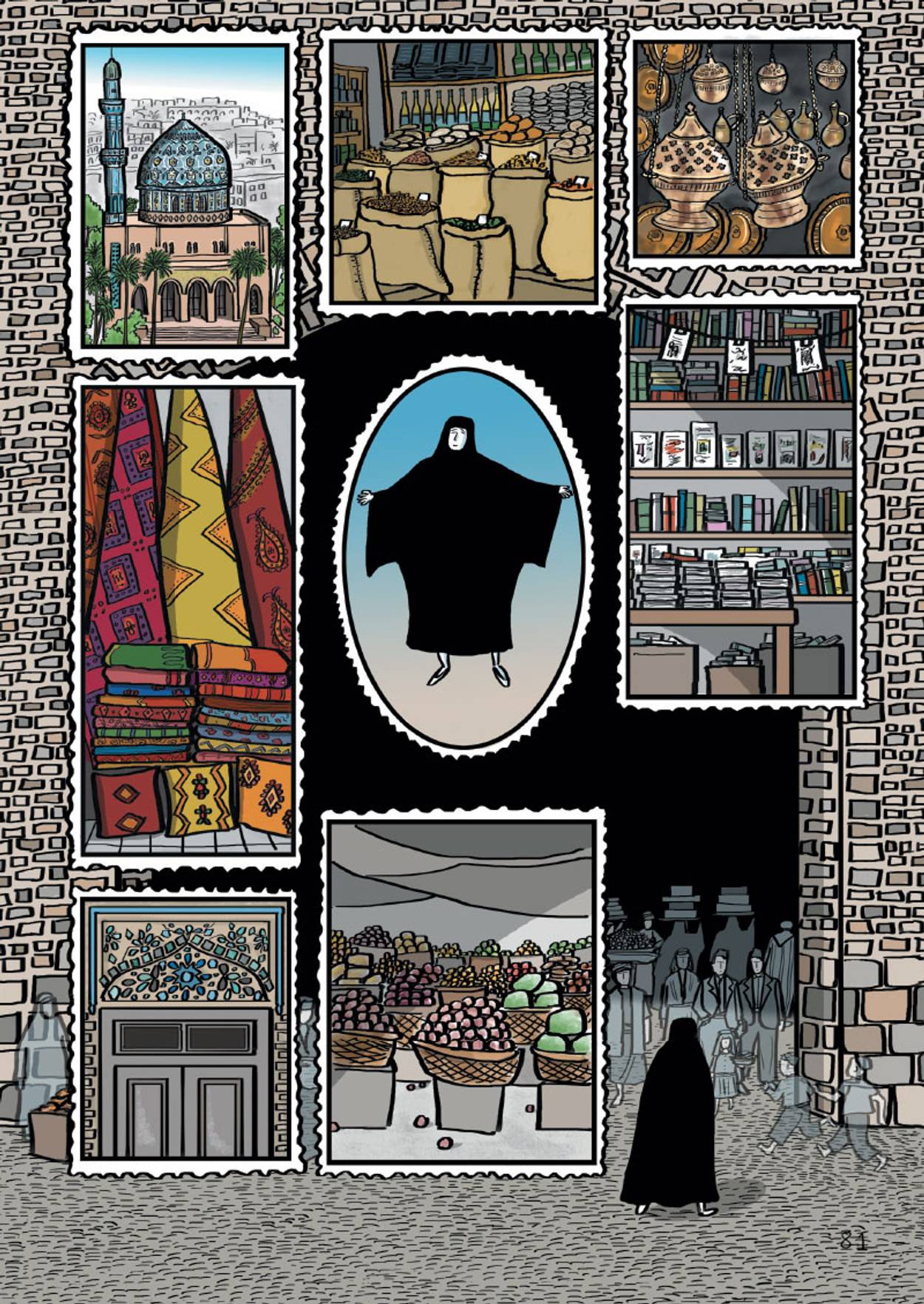

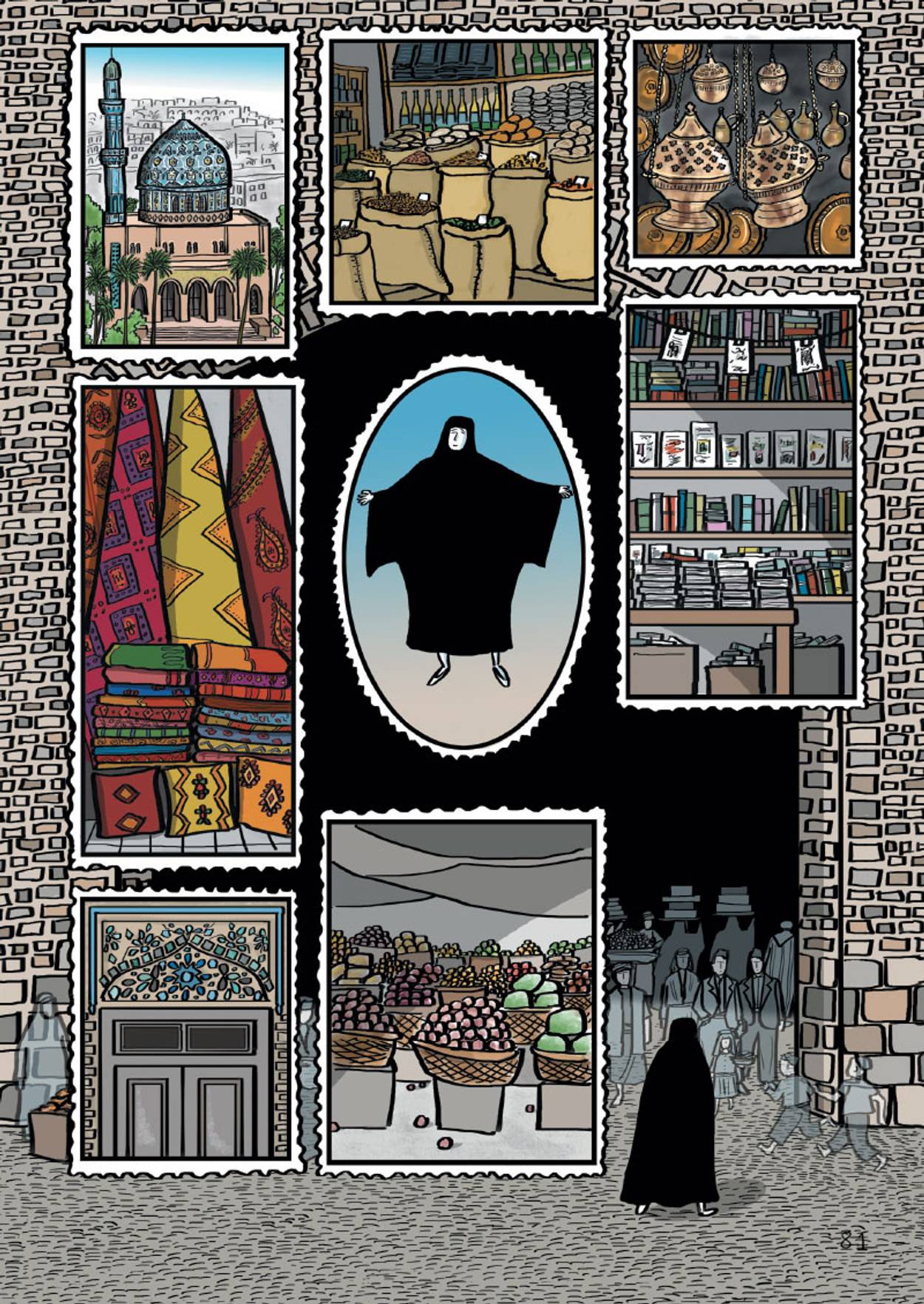

In The Wolf of Baghdad, Isaacs, who has never been to Iraq, places her present self into the imagined past of her ancestors. At the outset of the narrative, her graphic avatar is transported from a torpid evening in the company of family photographs in her northwest London apartment by music to an ancestral Baghdad. She navigates the city—now inhabited by ghosts—as an observer under a cloak, the same abaya her grandmother used to wear to pass unnoticed in Arab society. The figures she encounters are defined by their translucence: disembodied references to a once richly tangible world. She and they walk the same paths, but separately. The absence of talking in the action of the novel affirms the distance intervening between Isaacs and the Iraqi Jewish experience she portrays.

At the outset of this book, the faces of Isaacs’ family are arranged as portrait miniatures hanging like dates from a tree. The graphic narrative alternates with pages of sparse testimony, provided to Isaacs by her family and other Iraqi Jews, paired with portraits of their younger selves shaped like postage stamps.

Isaacs wanders through the various 20th-century Iraqs to which the community adapted until their demise. There are visions of old domesticity—sitting in the open air of courtyards, scents wafting up from cellars—and brief vistas of modernity: lawn gatherings and nightclubs. Superstition declines: The wolf evoked in the title was believed by Iraqi Jews to provide protection from demons; amulets made of their teeth were fixed to babies’ cribs to ward off the evil eye. But moving to a “European style” house dispels fears of djinns. Ottoman robes and tarbushes give way to office suits and blouses.

The possibility of a middle-class life, accompanied by slowly growing educational possibilities and secularization, existed for some Iraqi Jews in this period. “The process,” wrote recently deceased Iraqi Jewish author Sasson Somekh, “accelerated only after the British occupation in 1917, when the middle class—to which my family belonged—became the vanguard of renewal.” Isaacs draws her father driving across the desert to Palestine: his company was building a road through Transjordan, and during WWII, he provided the British army with European supplies.

The tenderness of Baghdad life—lengthy ambles through wide streets and narrow markets, fresh bread stuffed with mango pickle handed out at school gates, floating along the Tigris on palm tree bark—ultimately gives way to horror: upheaval, pogroms, expulsion. But Isaacs first evokes the sense of deep-rootedness and an assumed future that Iraqi Jews felt in their prime.

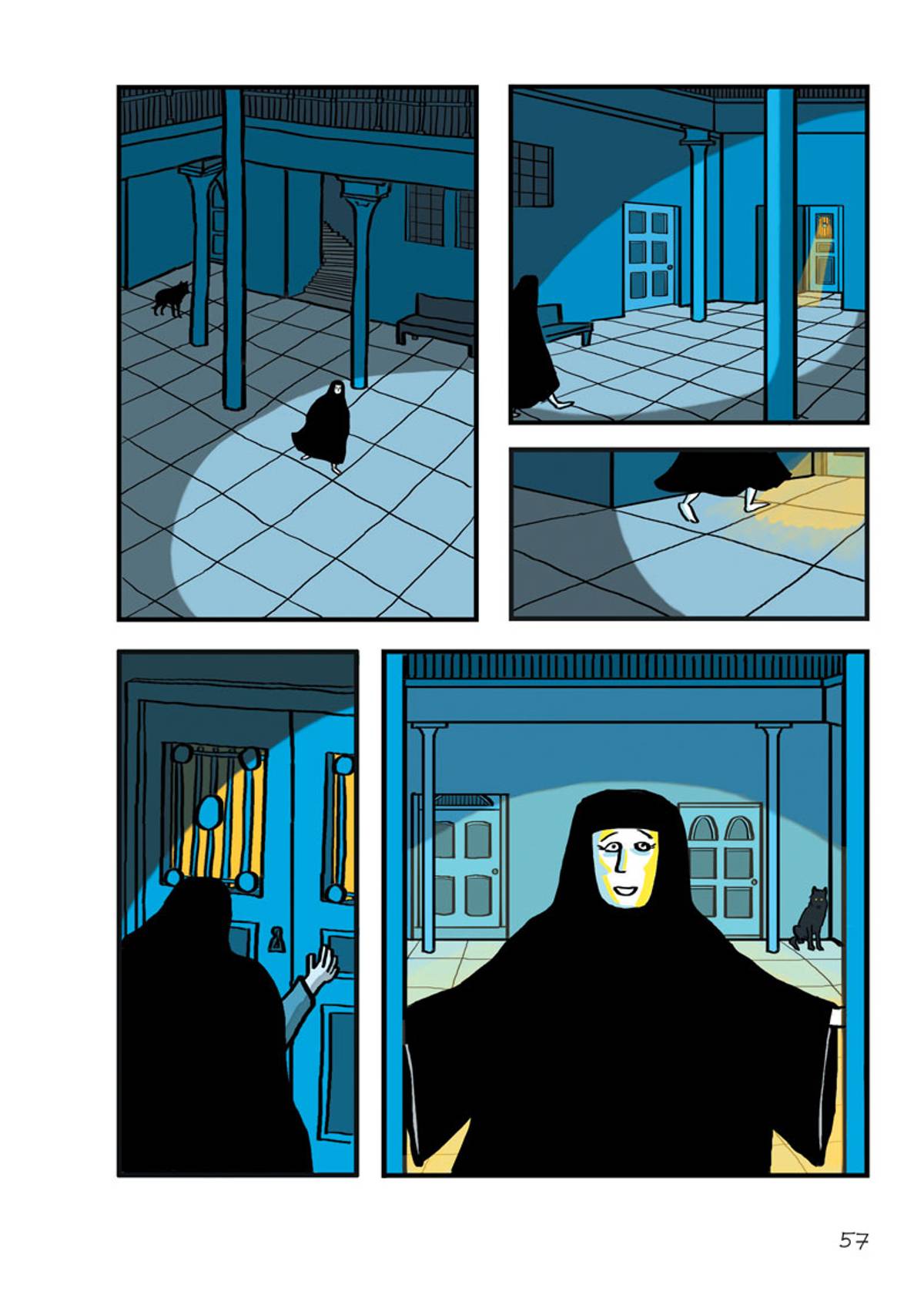

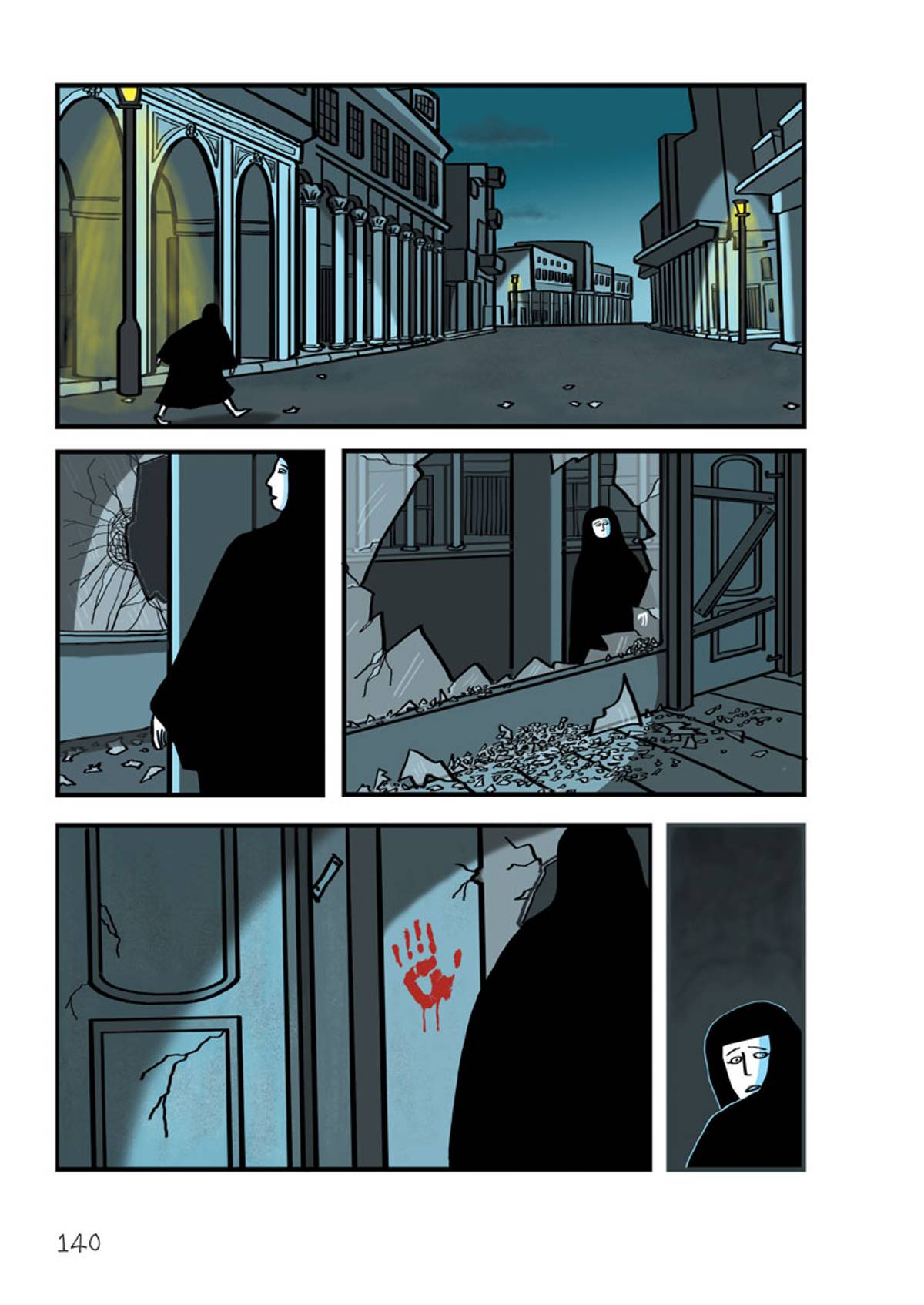

Isaacs handles the explosion of Iraqi Jewish life into oblivion by dampening colors and narrowing public space. The atavistic logic of anti-Jewish mobs is made self-evident through their lupine aesthetic. One page makes a swastika in the white space between drawings of Amin al-Husseini pouring coffee for a visiting German official and Arab crowds gathering against Jews. Soon, the names of Jewish musicians are removed from compositions, families bury Jewish symbols in their yards, and Jewish homes are marked.

For the final generation of Iraqi Jews, history contained both of a seemingly boundless past and, latterly, an abrupt series of overhauls. Isaacs sees the contours of figures and panels as analogs to phases of historical time. As anti-Semitic violence takes hold, Isaacs fragments images across several panels. Figures central to the drama outgrow their panel fragments as their sense of consciousness expands beyond the moment.

Isaacs’ play with contours is also visible in her evocation of Iraq’s topography; the mysterious fragility of Iraqi life is conveyed through its vulnerability to the elements. The indistinct periphery of desert—the nuances of its moods shown in shifting hues—almost seems to invite assault and erasure. In one passage depicting the kidnap of an Iraqi Jewish child by Arab sheikhs, panels are only bordered by the significant blank space between them. The following pages depict a sandstorm, across panels that show a huddled family seeking refuge and Isaacs struggling to see clearly, as the city is engulfed in a granular haze that even covers the insides of homes.

The “ancient lights” that Somekh described enchanting his childhood are here “fascinating but also frightening” to children going through the classic Baghdad rite of passage: sleeping on the roof. It is from the roof that sleeping children are eventually awoken by screams coming from the Jewish quarter during a night of violence.

Isaacs seeks to recover experience through a search for lost detail. But she also seeks the wisdom to transcend historical linearity. The wolf of Baghdad—which occasionally lurks behind Isaacs in her ramble, or flashes its eyes—accompanies Isaacs during the last phase of her foray through the ransacked Jewish spaces of the city. She notices that the family portraits in the ruined homes now consist merely of hollow outlines. She lies down in the darkness as the wolf begins howling the same melody that twists through the sky and reaches Isaacs at the start of the novel. She wakes in London to find a wolf-tooth amulet pinned to her.

A charming afterword attempts to pull together the remaining threads of the Iraqi Jewish experience, pointing to a network of new correspondents Isaacs has acquired through shared roots. The sketches, notes, and letters collected here are vestiges that underscore the oscillating status of these disappearing connections and memories. The story of Iraqi Jews has been over for many decades; the versions of Iraq they inhabited are unrecoverable from the Iraqi present. Interest in reigniting links is severely constricted by Iraq’s extreme instability and ongoing non-recognition of Israel.

Within the pages of Isaacs’ book, musical notes drift across panels and between periods of time. The nearly traceless vanishing of Iraqi Jews is conveyed through this depiction of music, whose rise and fall is only partly redeemed by its portability.

Mardean Isaac is a writer and editor based in London. Educated at Cambridge and Oxford, he has written for publications including the Financial Times, Lapham’s Quarterly and New Lines magazine.