Would I Have Survived?

As the daughter of Polish Holocaust survivors, I ask myself that question

Would I have survived?

As the daughter of Polish Holocaust survivors, I ask myself that question.

The chances were nil. Approximately 2% of Polish Jews survived the war within the borders of Poland. Looking at the stories of survivors close to me, I find that in each there was a pivotal moment, a hairsbreadth, split-second decision that made the difference between life and death. What would I have done? I know myself well enough to conjecture while keeping in mind that the circumstances were extreme and it’s impossible to know for sure.

The Nobel Prize-winning Polish poet Wisława Szymborska says in her poem, “Could Have,” that surviving was mostly due to luck.

You were saved because you were the first,

You were saved because you were the last.

Alone. With others.

On the right. The left.

Because it was raining. Because of the shade.

Because the day was sunny.

You were in luck—there was a forest.

You were in luck—there were no trees.

Szymborska says it was chance, “A rake, a hook, a beam, a brake, a jamb, a turn, a quarter inch, an instant.”

And, of course, she is right. You could have blue eyes, blond hair, speak perfect Polish, have money and jewels to bribe Poles into hiding you, be brilliant, intuitive, persuasive, decisive, alert, full of courage, physically fit, able to endure cold, hunger, pain, but still be killed because of a “a quarter inch, an instant.”

“There was no formula for survival, no rules. It was random, and the biggest factor was luck,” says David Silberklang, senior historian at the International Institute for Holocaust Research at Yad Vashem.

My mother’s first husband, Herman Fechter, was saved because of soup. It was his luck that his mother sent him on an errand to bring a pot of soup to two cousins hiding in the home of a Polish friend. The Pole, forewarned of the upcoming aktia, urged Herman to stay.

A few hours later everyone was killed while Herman watched from the roof, biting his hand to suppress a scream.

Random, arbitrary luck played a daily role in the survival stories of people close to me, a dodge, a close shave, but in each there was also something else, a decision to be made.

“From my conversations with survivors, their awareness of their surrounding and determination gave them the ability to react in a split second and make decisions that meant the difference between life and death,” says Silberklang.

Take my father, for example.

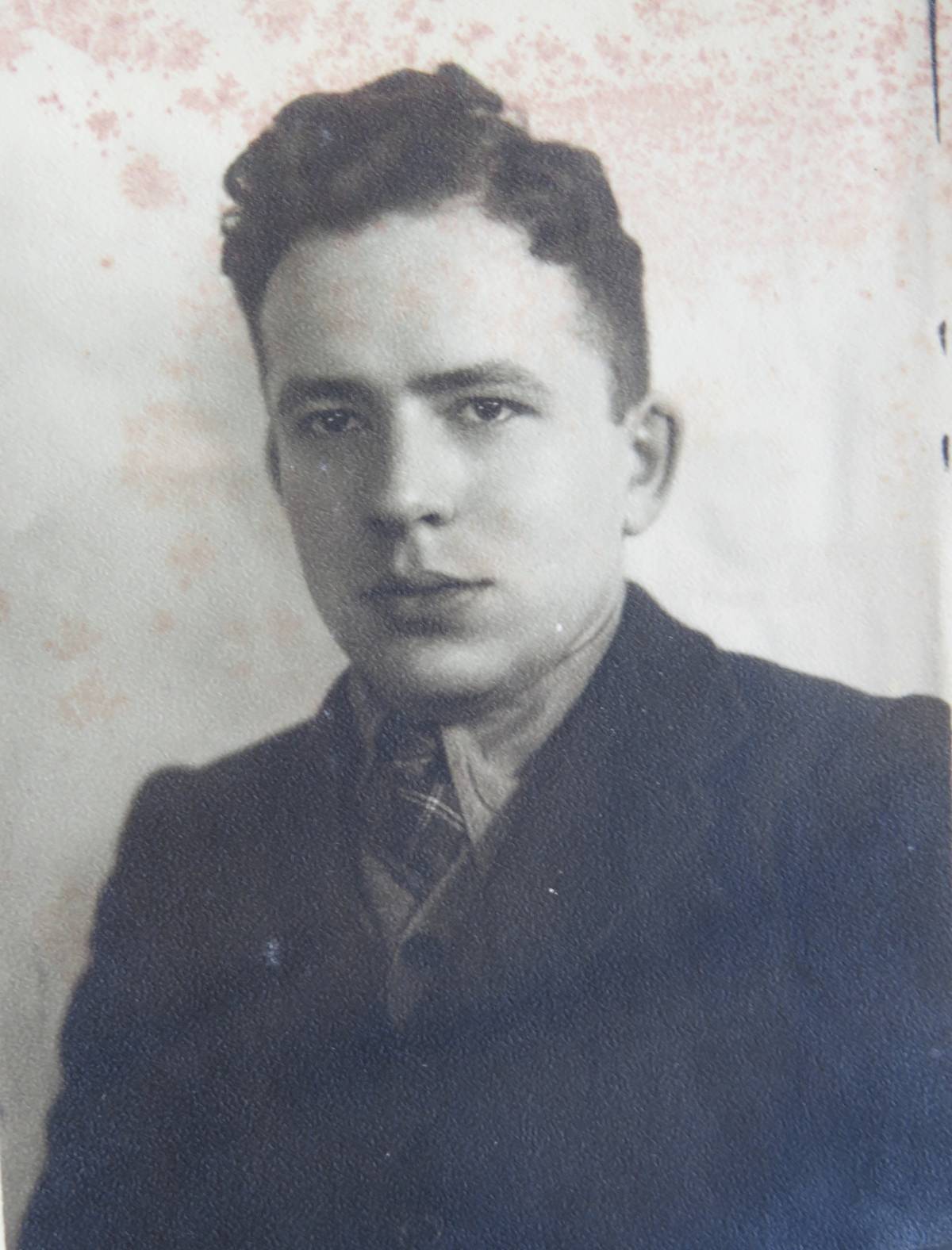

Shmuel Nussbaum, was 32 years old, married, and had a 5-year-old son, Moshe, on Dec. 17, 1942, the day of the final liquidationof Jews in Baranowicze, a town in Eastern Poland, now in Belarus.

He’s on a narrow wooden ladder, one foot after the other, legs shaking, out of breath, heart pounding, fear driving him up. He hears the crying, the shots, the terror, but he hesitates.

Moshe, his 5-year-old son, is in another part of the ghetto with his wife. The ghetto is split into two parts with a narrow passageway between them. Does he continue to climb to the attic and abandon his wife and child or climb down and find them so he can shield them in their last moments when they are shot, their bodies thrown into a pit?

His sister, Esther, urges him from below.

“Hurry up, Shmuel. I’ll take away the ladder.”

“What about you?” he asks.

“No, I’m going out to look for Fyszel,” her husband.

My father climbs and slips his body into the small hiding space in the attic.

His sister hides the ladder.

He abandons Moshe, his wife, and his elderly mother, Frieda Suchodolski Nussbaum.

He would have abandoned me.

But I exist because he chose to abandon his son.

He stays up there while the Germans search for bunkers, false walls, attics. He gets lucky. They don’t find him.

At night, once the ghetto falls into silence, he jumps down and makes his way to a bunker in his sister and brother-in-law’s beer factory, a franchise of the Haberbuch and Schiele Company. Here is the second stroke of luck. Three months earlier, after the second aktia, his brother-in-law, Fyszel Sawczycki, and Jewish workers, secretly dug a bunker in the basement under the ice.

They equipped it with electricity, small holes for ventilation, and supplies. A Belorussian worker loyal to Fyszel was in on the secret. He would come every night and knock twice on the floor to let them know it was safe to come out to stretch their legs. He brought them food.

Fyszel had hidden there for a few days before the final aktia but changed his mind and returned to the ghetto. He was a member of the Judenrat, in charge of economic affairs.

“It’s not right that I am here,” he told the others. “It’s not right that I save myself and abandon the ghetto.”

My father had nothing but endless time in the dark to contemplate his decision.

About five months later it became too dangerous to stay.

Here is where another stroke of luck comes into play: topography. Close to Baranowicze is one of the last and largest remaining parts of the immense primeval forest that once stretched across the European plain. They left that night and walked 15 kilometers to the forest where several partisan groups operated, among them that of the Bielski brothers. My father joined a fighting group and survived until the end of the war.

In this scenario I am dead.

I would have never climbed that ladder. I can’t imagine any circumstances where I would have abandoned my child.

After my first son was born, I went for therapy. I had disturbing, frightening thoughts that I am standing in a long line holding my beautiful baby in my arms making my way to Josef Mengele. The thought of being helpless to save my baby was impossible to bear. Were these fears transmitted from my father?

My father only spoke about Moshe once. He told me, almost in a whisper, that he knew he couldn’t bring a 5-year-old boy into a dark bunker where absolute silence was required. He also knew his wife would not abandon the boy. Only three Jewish children are known to have survived from Baranowicze.

When I was about 12, my father and I watched a movie on the black-and-white TV that ends with an emotional reunion of a father finding his long-lost son. A choked, strangled cry escaped my father.

There was nothing I wouldn’t do for him to bring joy into his life. I loved him so much, a tender, protective love, and I was never stingy letting him know it.

He lived long enough to see his two grandsons born. In the hospital while I was making lists of names, he wrote a few suggestions on the page, none Moshe.

In the next story I am dead too, and because of a sip of water.

My cousin’s cousin, Eva Kracowska, was a member of the Bialystok underground, which staged an insurrection on Aug. 16, 1943, the final liquidation of the ghetto. It was the second-largest uprising after Warsaw, which took place four months earlier.

As soon as the aktia began, she reported to her preassigned spot on the ghetto fence on Smolna Street where homemade Molotov cocktails were already in place.

“The plan was to die there and not go on the transport,” she said in an interview for Yad Vashem in 1997. “This I swore to myself. I knew Smolna Street would be my end.”

The Jewish fighters had 25 rifles, 100 pistols, as well as the Molotov cocktails.

Outnumbered and surrounded, they fought against overwhelming German firepower, including armored cars and tanks.

When the situation was hopeless, a male friend pulled Eva away through a series of backyards to a hiding place in an attic. For two and a half months, a few of them stayed in a tiny protruding wing that had been built for decorative purposes on all four corners of the building. Anyone coming into the dark attic could not see them. At night the band would come down to look for food and water in abandoned apartments. Nearby, they found a barrel of acrid water with algae growing in it. There was no other source.

During the day Germans and Ukrainians searched the building, at first, several times a day, knocking on walls, stomping on floors. Several weeks later, Polish workers began clearing out furniture and searching for gold the Jews may have hidden.

On Nov. 1, Eva and her two friends managed to slip away at night and walked 30 kilometers to the forest.

Up to this part I think I could have survived.

Now comes the test.

The three friends are in the forest. They are frightened, exhausted, hungry, elated to have escaped, but more than anything else, they are bone-dry thirsty. Parched. They had been eating roots they found in the harvested fields but could not find water.

They spy a small village near the forest.

She has a split second to decide. Does she drink the water, or open the window and jump?

The two men decide Eva should knock on the door of the closest house and ask for water. Eva had a “good look,” a “goyishe” face and spoke perfect, unaccented Polish.

Eva summons her courage and walks through the field to the simple, one-story village house. She knocks.

A middle-aged man opens the door and is surprised to see her. His teenage son comes to the door as well.

“Good day,” she says politely trying to look and sound natural, as if it is not strange that she is wandering alone in this remote area, dirty, disheveled. “Prosze pana, may I trouble you for some water?”

“Prosze Pani, please come in,” he says politely.

He ushers her to the next room, offers her a seat, and goes to fetch a jug of water and a glass.

He sets them on the table and leaves her alone in the room.

Eva reaches for the jug, imagining the cool water in her mouth, when she hears the turning of a key in the door. She is locked in.

She has a split second to decide. Does she drink the water, or open the window and jump?

She leaps and runs for her life through the field, while shots are fired behind her. The three survivors of the Bialystok ghetto depart in haste, still thirsty, but alive. They find a partisan group and survive the war.

I know myself well enough. I would have decided to take a big gulp of water, just one, and then I jump out the window. I would have reasoned that I had time to do both. That one sip would have likely cost me my life.

On the day of the Bialystok ghetto liquidation, while Eva escaped to the attic hideaway, her future husband, whom she did not know at the time, was loaded into a packed cattle car heading to Treblinka. Yosef Makowski was a carpenter by trade. When the Germans shut the door, the closing of the bolt made a clicking sound and Makowski, 23, marked the spot. He obtained a pocketknife and a hammer from some of the other prisoners and made a hole large enough to put his hand through to lift the bar. A Ukrainian guard who rode shotgun on the roof of the carriage noticed Makowski’s work and began shooting into the carriage. The train stopped and the guards fastened the bolt securely with barbed wire. The train was 4 kilometers away from Treblinka by the time Makowski cut the barbed wire and opened the door. He and others jumped off. Some were killed by bullets as they tried to flee, others injured by the jump. Makowski’s instinct for survival took over and he dropped down by the track rather than run. The bullets whizzed over him. Luckily, this time the train didn’t stop. Perhaps German punctuality dictated that the passengers must arrive on time for their prescheduled appointment in the gas chambers. Makowski and four others began a two-week, 100-kilometer trek back in the direction of Bialystok and joined a partisan group, which is how he met Eva.

In this scenario, I would not have had the technical skill to open the door, but once opened, heart pounding, legs trembling, I would have taken a leap of faith from the moving train. At least 764 Jews are known to have survived the Holocaust by jumping out of moving trains, according to Tanja von Fransecky, a German historian who spent four years researching the subject for her study “Jewish Escapes from Deportation Trains.”

“In sealed box cars, travel names across the land,” writes Szymborska in her poem, “Still.”

“Don’t jump while it’s moving. Not time yet. Don’t jump. The night echoes like laughter mocking clatter of wheels upon tracks.”

I suffer from claustrophobia and therefore had no chance to survive in this next story. My husband’s cousin Genia Kopf found refuge with a Polish neighbor who had been kind to her family. He dug a hole in his barn for her to hide. It was not large enough to lie down or even sit up, just crouch, legs folded. For almost two long years, entombed in the pitch black, she could hear children playing, dogs barking.

This is the part where I climb up, arms raised, and ask someone to shoot me.

I have claustrophobia and can’t imagine staying in the hole for two hours, never mind two years. I’m certain I got it from my father who hid five months in the beer factory bunker. He always complained that there wasn’t enough air in the room because my mother, in her battle with Florida humidity, kept the windows closed. He spent most of his time on the small balcony watching boats sail by in the Intercoastal.

So, any survival tactic that required staying in a dark, confined space would have been out of the question.

The next survival story is so extraordinary, shows such ingenuity, such brilliance, that maybe one in a million could have pulled it off, maybe even one in 6 million.

The father of friends of ours in Vienna was 13 years old when he arrived in Auschwitz on Oct. 18, 1943. When Dr. Mengele asked his age, he said 18. When Mengele asked if he had a profession, he improvised and said an electrician.

Two months later, he faced a big selection, which he realized he was not likely to survive. He hid outside his barracks when suddenly he was confronted by an older SS officer pointing his gun at him demanding to know what he was doing there. He managed to talk his way out of certain death by appealing to the German’s parental instincts.

After the selection, he was sent to D Lager, where he realized that he had no chance to survive due to the severe living and working conditions.

This is where, in a stroke of genius, the teenager went to the quarters of the Sonderkommando and asked permission to hide in their barracks during the day and return to his own at night.

He got away with hiding there every day for almost a year, until October 1944.

Like I said, this was one in a million.

The thought of whether or not they would have survived is common among the second generation, says Hani Oron, former director of AMCHA, Israel’s largest provider of mental health and social support services for Holocaust survivors and the second generation.

“I personally thought about this question many times,” says Oron, whose mother survived Bergen-Belsen. “In my childhood, when she thought I was being spoiled, my mother would say to me ‘you wouldn’t have survived 15 minutes in the camp.’ I came to the conclusion that I would have survived because I am a fighter and I have a passion for life. This is an emotionally charged subject that will preoccupy generations to come.”

So, I ask myself, would I have survived?

Not likely.

The statistics are overwhelmingly against it.

The biggest piece of luck in my life is the timing and place of my birth, nine years after the end of World War II in Israel, the first generation of Jews born in the newly formed Jewish state. My little brother, Moshe, born in Poland in 1937, wasn’t so lucky.

“So you’re here?” Szymborska asks at the conclusion of her poem about survival.

Still dizzy from another dodge, close shave, reprieve?

One hole in the net and you slipped through?

I couldn’t be more shocked or speechless.

Listen,

how your heart pounds inside me.

This article is part of a series for Yom HaShoah.

Shula Kopf, a former reporter for The Miami Herald, is a freelance writer based in Tel Aviv.