Writing the War

Elliot Ackerman’s latest book about the fall of Kabul establishes him as a master of his genre

With the Dreyfus affair, France invented the engaged intellectual.

In Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, the United States invented the participant veteran writer. I’m thinking of Karl Marlantes and his Matterhorn. Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried. Kevin Powers’ Yellow Birds, and Phil Klay’s Redeployment.

The demobilized hero is a very American literary figure, haunted by the horror of what he’s lived through, shadowed by Hemingway-esque regrets, publishing his first short story in Granta, essays in Esquire, and, with enough talent, setting to literature.

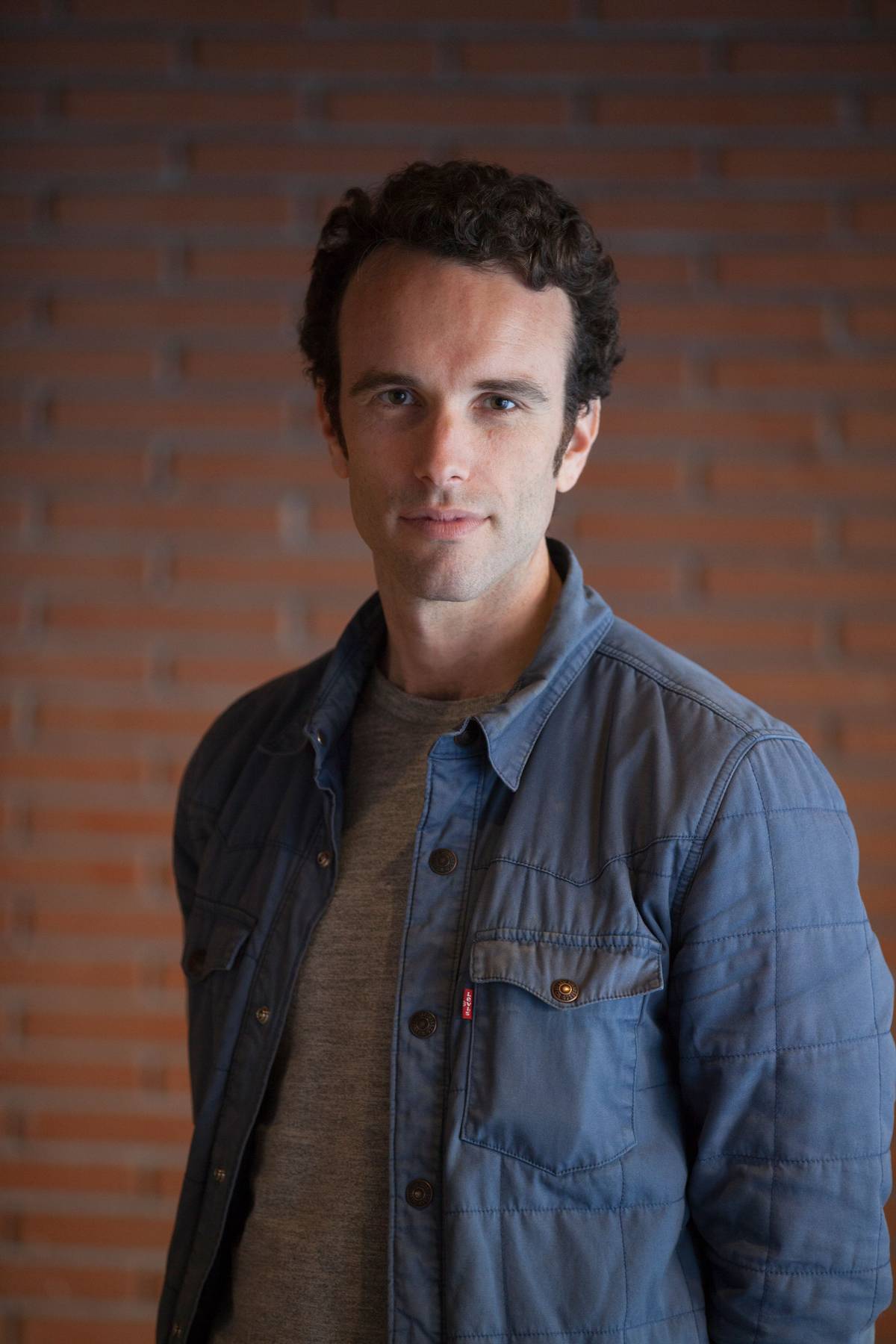

Elliot Ackerman is a 42-year-old New Yorker who spent 10 years in the Marines and Special Ops for the CIA; got all the Silver Stars, Bronze Star for valor, Purple Hearts; and served the end-of-epoch Obama White House and the most prestigious think tanks in Washington D.C. He is becoming one of the masters of the genre. His seventh book, from Penguin, is titled The Fifth Act: America’s End in Afghanistan.

In principle, The Fifth Act is an account of the fall of Kabul, that self-inflicted Saigon which came about after Trump, then Biden, decided to be done with a war that, in reality, they had won.

But the book is more than that. The beauty of it is that it unfolds across three, or even four, registers. There is a father who had promised his kids a dream vacation to Italy and who, despite events, keeps his word: the Forum, a toy store at the Coliseum, the baths of Caracalla, Venice.

There is an American hero who knows that his country is making a historic blunder in letting go of Kabul, and that that error would become a colossal mistake if it left behind the tens of thousands of journalists, interpreters, or fixers who had believed its word and would become, after its departure, the main target of the Taliban. We watch him, at night as his family sleeps, or during the day, between visits to museums, joining WhatsApp and Signal threads where a network of former comrades tries, from points around the globe, to run evacuations. We see him communicating urgently with “Yeti” the giant, “Knuckles” the old sergeant, and “Dutch” the eccentric, these old companions in the field, gathering up candidates for departure, putting them on buses, escorting them; and we see him, glued to his screen, following the GPS position of a convoy, losing it, finding it again, shuddering at the thought of the passengers being blocked at the final checkpoint, a few meters from the airport, and breathing again once he understands that they made it through.

There is a third voice, that of the former soldier who feels stirring within the ghosts of his own past in Afghanistan, and before that, in Fallujah, in Iraq. There he is during an operation, on board his Humvee; there he is with “Tubes,” “Dud,” and “Super Dave,” going to fetch the body of a killed comrade that the code of the Marines won’t permit them to leave behind; there’s the death, as it happened, of the courageous Sgt. Dave “Momez” Nunez, for which he blames himself; and there he is reliving his last conversation with “Jack,” his friend and superior, whom he has come to inform that he’s quitting the armed forces. Did “Jack” ever forgive that? And isn’t he the one responsible today, by some strange twist of destiny, for the fate of those 109 men they swore to help save from afar?

And then come some weird and haunting images … The decapitated heads in the mosaics of the Torcello Basilica irresistibly evoke for him the fate that await his Afghan friends if they can’t get them to the other side of the fences around Hamid Karzai airport ... A parade of pious and somber thoughts on the indignity of the war ... What little attention he paid, in his life as a decorated soldier, to the ancient commandment not to kill … The decline of empires … A way to honor Doug, Megan, Blecksmith, and all the comrades who, unlike him, never made it back from Fallujah.

This structure isn’t just wise. It is wonderfully Romanesque. At times, we are in a Roberto Benigni film, where the hero deploys treasures of the imagination to amuse his little son before the gates of hell, to make him believe that life is beautiful.

At other times, we are in the best scenes of Barry Levinson’s film Bugsy, when Warren Beatty is caught between the kitchen where he’s preparing his son’s birthday cake and the living room where his Mafia associates have come to settle accounts.

And when Ackerman describes the sunset over Shewan, the landing of Black Hawks in the dust of a battlefield, the transformation of a refrigerator into a morgue, the cries of the wounded mixed with those who have come to save them, or the agony of a brother in arms, we are among the best in war literature, like Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead or Hemingway.

Read this book.

Translated from French by Matthew Fishbane

Bernard-Henri Lévy is a philosopher, activist, filmmaker, and author of more than 30 books including The Genius of Judaism, American Vertigo, Barbarism with a Human Face, Who Killed Daniel Pearl?, and The Empire and the Five Kings. His most recent film, Slava Ukraini, premiered nationwide on May 5, 2023.