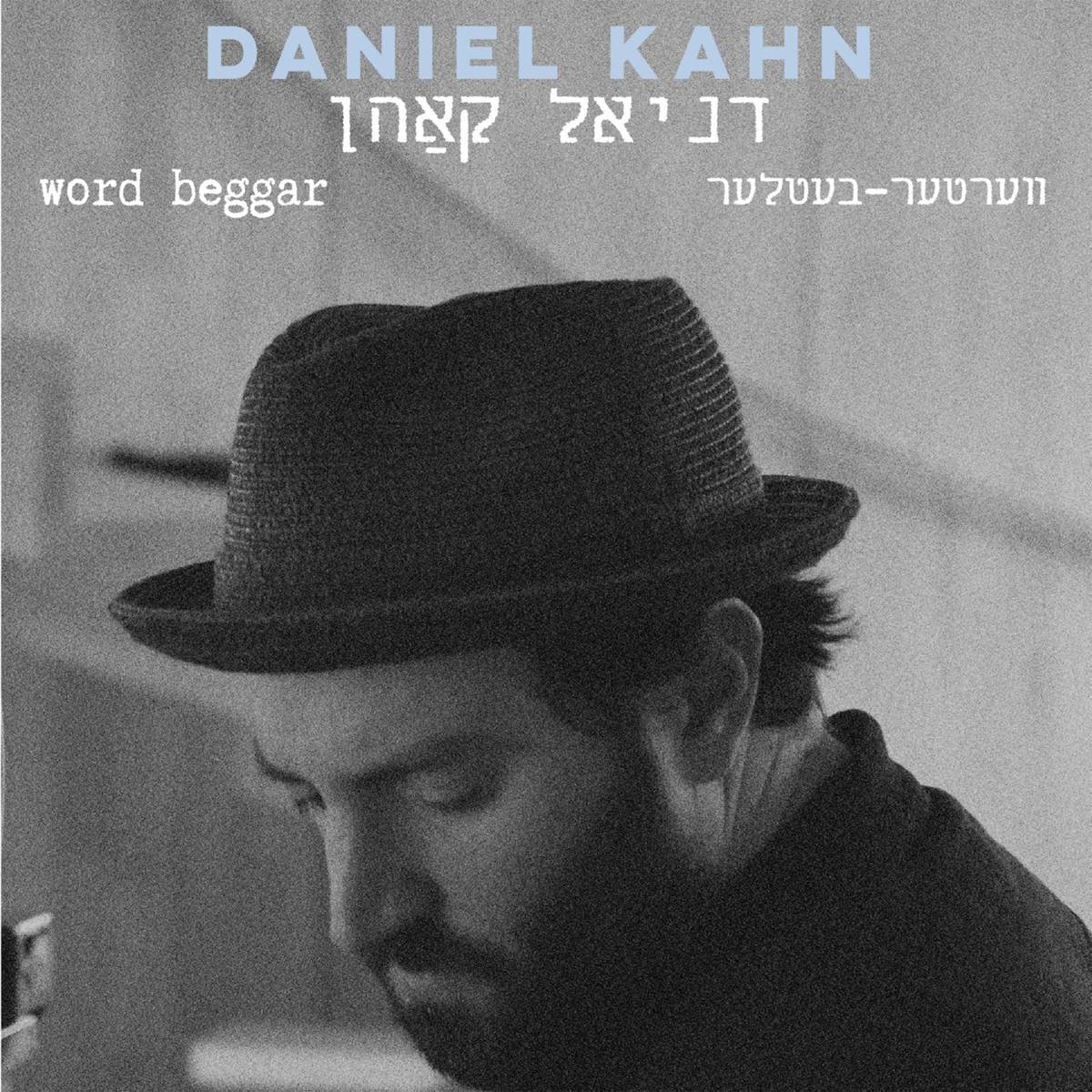

The Yiddish Bard of the 21st Century

In his new album, Daniel Kahn is a lyric beggar at the Jewish cemetery

The first few times I heard Daniel Kahn sing, I had a distinct sense that he belonged to another era. That feeling had little to do with his Yiddish songs, or his Jewish work songs, or his accordion, or his lush diction and rhyme which I associated with Romantic poets of the 19th century. It was something else, something about the quality of his voice: a slight growl, and a smirk that can turn fragile, flaring at a moment’s notice to invoke a lyric and historic elsewhere. It wasn’t until I listened to his recent album, Word Beggar, that I understood where his music took me.

With the album, sung in Yiddish and English, on repeat, I realized that Kahn is a bard, in the ancient sense of that word. He’s a bard of the sort you may have found roving through the world a century or a millennium ago, or even further back, all the way down to the earliest human attempts to capture their moment in history and convey it in poetic mythology.

The album’s title, Word Beggar, comes from a short, haunting poem by Aaron Zeitlin, originally published in Yiddish in 1947, which Kahn translated and set to music:

SIX LINES

I know, this world will never find me necessary,

me, a lyric beggar in this Jewish cemetery.

who needs a song—let alone in Yiddish?

the only beauty in this world is in hopelessness & pain,

and godliness is only found in that which won’t remain,

and the only revolt is in submitting.

The poem has recently gathered momentum: The Yiddish Book Center held an event this year featuring numerous translations, including Kahn’s. Though brevity is the central characteristic of the poem—as underscored by the title itself—it packs enough heartbreak to embrace a century’s worth of Jewish history. Who in the world would “find” the poem’s beggar “necessary”? If anything, it is the opposite—the beggar is usually seen as a sore thumb, a parasite, who continues to take without giving back. This, of course, would be the view of a culture that measures a person’s worth through its “necessity” or usefulness. Thankfully, other paradigms exist too, and the poem is a yearning for these other worlds.

As a child in Ukraine, I frequently encountered scores of folks asking for alms at the cemetery’s gate, perhaps because it is there that one’s sense of humanity is heightened by the proximity to one’s own mortality, with feelings of loss sharpening one’s need to do what’s right. In that way, to be a poet, especially a Yiddish poet, is not terribly different from being a “beggar.” Poetry is not “necessary” in any kind of a utilitarian sense, but our humanity hinges upon its existence. The fact that poets routinely take up the subject of mortality, and tragedy at all, is perhaps not unrelated to the reason why the despondent come to the graveyard.

So what does it mean to be “a lyric beggar” at the Jewish cemetery? The sort of cemeteries Zeitlin wrote about are long gone. There’s no one there to beg from, except for the dead. The gifts, then, also belong to the world of the dead: memories and visions, losses and language. If T.S. Eliot famously quipped: “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal,” Kahn’s vision of a poet-translator as the beggar of the dead offers a stark alternative. “It’s not as violent,” he told me in an interview, “not as subversive, it’s a little more honest maybe, and maybe more ideal than other metaphors. At the end of the day, the thing that’s given to you becomes yours. And what you do with it is nobody’s business.”

My conversation with Kahn took place over Zoom. He appeared to be in a small workshop-museum room in the harbor of the city of Hamburg, Germany, where he now lives with his partner, St. Petersburg-born dancer and translator Yeva Lapsker, and their son—on a boat. It is a rare artist who not just performs his work, but embodies it as well, and it was impossible to ignore the inherent symbolism of Kahn’s aesthetics of diasporism. It was a Jewish artist’s vision as a life rocked by constant motion, a few steps removed from sturdy ground.

Kahn’s new album contains Yiddish poems set to music, often with English verses alternating throughout the song. It also contains three songs he translated into Yiddish from English—Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released” and “I Pity the Poor Immigrant,” as well as Cohen’s “Hallelujah.” The latter track, released by the Forward as a video, went viral some years ago, garnering over 2 million views. It is a virtuosic work, to be sure, with a translation rich in phrases that reference both colloquial and spiritual Yiddish vocabulary, and therefore accessible for someone like me who doesn’t speak Yiddish but is familiar with Jewish cultural references enough to contextualize their significance in the song.

Kahn’s translation was so masterful that the producers included subtitles, translating Kahn’s Yiddish back into English. I asked him how he accounts for the explosive popularity of this work. How many people out there speak Yiddish, anyway? “Firstly, I can’t account for it because I am terrible at accounting,” he quipped. “And anyway, how many people speak Leonard Cohen? Very few. Lots of people love that song and have no idea what it’s about.” Clearly, Kahn not only speaks Leonard Cohen but also locates himself in Cohen’s bardic lineage, as a singer with a poetic sensibility and a prophetic stance. The video, released a few days after Leonard Cohen’s passing, served as a de facto tribute, and a passing of the torch.

Kahn does all the singing and plays all of the instruments on the album—piano, guitar, accordion, and harmonica. But his acknowledgment section is longer than an orchestra rollcall. At the end of the liner notes, he writes: “A hartsikn dank [hearty thanks] to the khaverim [friends] who’ve touched these verses & versions,” and includes an extensive group of Yiddish musicians and poets, scholars and artists. For a solo album, it’s a long list. “It’s anything but a solo album,” explained Kahn, “because it’s not like it’s mine. That’s also why it’s called Word Beggar: There isn’t a word on there that I didn’t somehow take from somebody else, in one way or another. The art of translating is as much an act of listening, reading, and receiving, and analyzing, and understanding, as it is an act of production or creation.”

The Yiddish revival, which by now spans over a few decades, is an attempt to engage with Yiddish literature, Eastern European Jewish history, and secular and religious culture. Its exponential growth is the result of the warm, encouraging, and collaborative spaces that made albums like Word Beggar possible. Kahn, who first became aware of the Yiddish revival in his early 20s after visiting the KlezKanada festival, recalled: “From the very beginning I was turned on by this scene because it was a scene … an incredibly fertile environment where people were collaborating across the lines of generations, across political lines, religiosity, national origins. It was a community and a conversation that I found fascinating … My involvement with Yiddish song begins and ends with taking part in that conversation.” In these circles, Yiddish is not an object of some half-baked sentimentalism, but a generative field of discourse, study, and transformation, or as Kahn put it, “it was the thing that was simultaneously learned about and created.”

Like other ambitious projects which stemmed from the Yiddish revival milieu, his album is also a research project and a master class. Like a true encounter with a bard, it is a lesson in personal and global history, and an attempt to right a historical wrong: “I didn’t grow up with this stuff,” Kahn told me. “I was not told about Itsik Manger, about radical Yiddish artists, these visionaries. It wasn’t a part of my Jewish education, or my secular education, it wasn’t a part of my world. And part of it was that they were all hidden behind the wall of not understanding Yiddish, but I don’t think it was a very good excuse because there were all kinds of other poets I knew in all kinds of languages I didn’t speak. It was a part of this willful forgetting, willful insult to that culture and those people, and that was the Jewish culture I was handed as a youth.”

Kahn grew up in a lower-middle-class suburb of Detroit and attended a Sunday school at the local Reform temple. Like many others, he now questions what happened to the Yiddish culture, which, after being nearly destroyed in the Shoah, continued to be erased by the mainstream Jewish establishment. I do not know if every revivalist has a manifesto on the tip of their tongue, but this bard-revivalist certainly did. When I pressed Kahn to articulate what it was about Yiddish itself that attracted him, without much ado he exploded with the following spontaneous manifesto-poem-rant (also pictured below):

“All the theory aside, all of the identity politics aside, all of the history aside, all of the cultural context aside, Yiddish is a goddamn sexy language. It’s a beautiful language. It’s tasty. It sounds good. It’s flexible. It’s a contortionist language. The musicality is baked in. It is so deeply colloquial and idiomatic; you get lost in it. You can never fully understand it unless you’re from one of the several worlds in which it grew. There’s there there. There’s content there. The content fascinates me, and the context is what we have to create on our own, because it’s not a language that has a holistically naturally occurring context … Every time we have a concert that has this content, we create a temporary island of context for it. We have to do it ourselves.”

Word Beggar certainly qualifies as an “island of context,” but it doesn’t hinge on sexiness and beauty alone. This album, like much of Kahn’s other work, demands rigor and commitment from its audience. Listening to Word Beggar is something of a project: I spent the first few hours following along with the liner notes, trying to trace the lyrics and connect them to translations, hoping for a sense of how music responds to the meaning of words. I spent a good deal of time Googling names of Yiddish poets, and the contemporary new-to-me Yiddish masters, alongside lyrics to Bob Dylan’s and Leonard Cohen’s songs. It was an immersive learning experience.

Of course, that’s not to say one that can’t sing along with the album or listen to it while driving. But you might sing yourself into taking an unexpected turn, and then you might end up on a boat, sailing across history.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).