Zoya Cherkassky, Hero-Tyrant

An interview with ‘Israel’s eternal dissident’ on her New York exhibition

©Zoya Cherkassky, courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort

©Zoya Cherkassky, courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort

©Zoya Cherkassky, courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort

In May, when I interviewed Zoya Cherkassky over Zoom, rockets were being launched at Israel from the Gaza Strip. “We’re having bombings today,” was the first thing the Ukrainian-born Israeli artist said to me, nonchalantly. “So, if there’s an alarm, I’ll have to run to the shelter. But I hope it will be fine.”

The missile fire, in fact, afforded no problem, though it was fitting backdrop for the fireworks often aroused by Zoya, whom Haaretz called “Israel’s eternal dissident.” Her recent show, The Arrival of Foreign Professionals, which ran from April 8 through June 3 at the Fort Gansevoort Gallery in New York, is combative and tender, humorous and accusative, piercingly observant and masterfully composed. The exhibit, composed of scenes from the African diaspora in Europe, Israel, and the former Soviet Union, has its origins in her own life as the wife of a Nigerian Israeli and the mother of their mixed-race child. Her husband, Sunny Nnadi, who came as a labor immigrant and recently attained Israeli citizenship, is memorialized in one of the exhibition paintings, “My Family at the Immigration Office,” which shows husband, wife, and toddler, exhausted and anxious, in a government office decorated with a string of cheap Israeli flags and an orange-colored sticker dispenser that says “Take a Ticket.”

©Zoya Cherkassky, courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort

In previous shows, Zoya chronicled her childhood during the glasnost era in Kyiv and her early years in Israel, where she moved with her family when she was 14, two weeks before the collapse of the Soviet Union. A well-known painting of hers, “New Victims,” shows their 1991 arrival, dressed in layers of Soviet winter clothing as they disembark from an El Al airplane. In a small series, “Lost Time,” dating from the beginning of the pandemic, she reimagined prewar Eastern European Jewish life as an analog to the deadly coronavirus. At the start of the war in Ukraine, she began to pair old compositions of her Soviet childhood with newly imagined ones, demonstrating how the Russian invasion of Ukraine had violated the intimate memories of her childhood. For instance, in the “before” version, a child (Zoya) stands by the window of her family’s Kyiv apartment and looks out at a snowy dark sky as someone familiar waves to her. In the newer version, a child stands in a similar pose by a similar window and looks out at military vehicles and fire blazing from a building across the road.

Since memory and group memory play such an important role in Zoya’s work, I wanted to ask about her family’s life and history in Ukraine. Both of her parents were professionals; her father was an architect and her mother an engineer. She told me that her grandparents came from three different cities—Odessa, Kyiv, and Vinnytsia—and family members survived the Second World War because they were evacuated. One of her grandmothers went to Tajikistan and the other was sent to what Zoya called “the far, far East, almost China.” Her mother’s father was a soldier in the Red Army, discharged after an injury left him without movement in his fingers. Her father’s father was an architect for military factories. One set of great-grandparents was too old to evacuate and they were killed at Babyn Yar. Zoya, who is far from sentimental, said abruptly “and this is what happened,” and then half-finished the sentence, “but it’s such an awful way …”

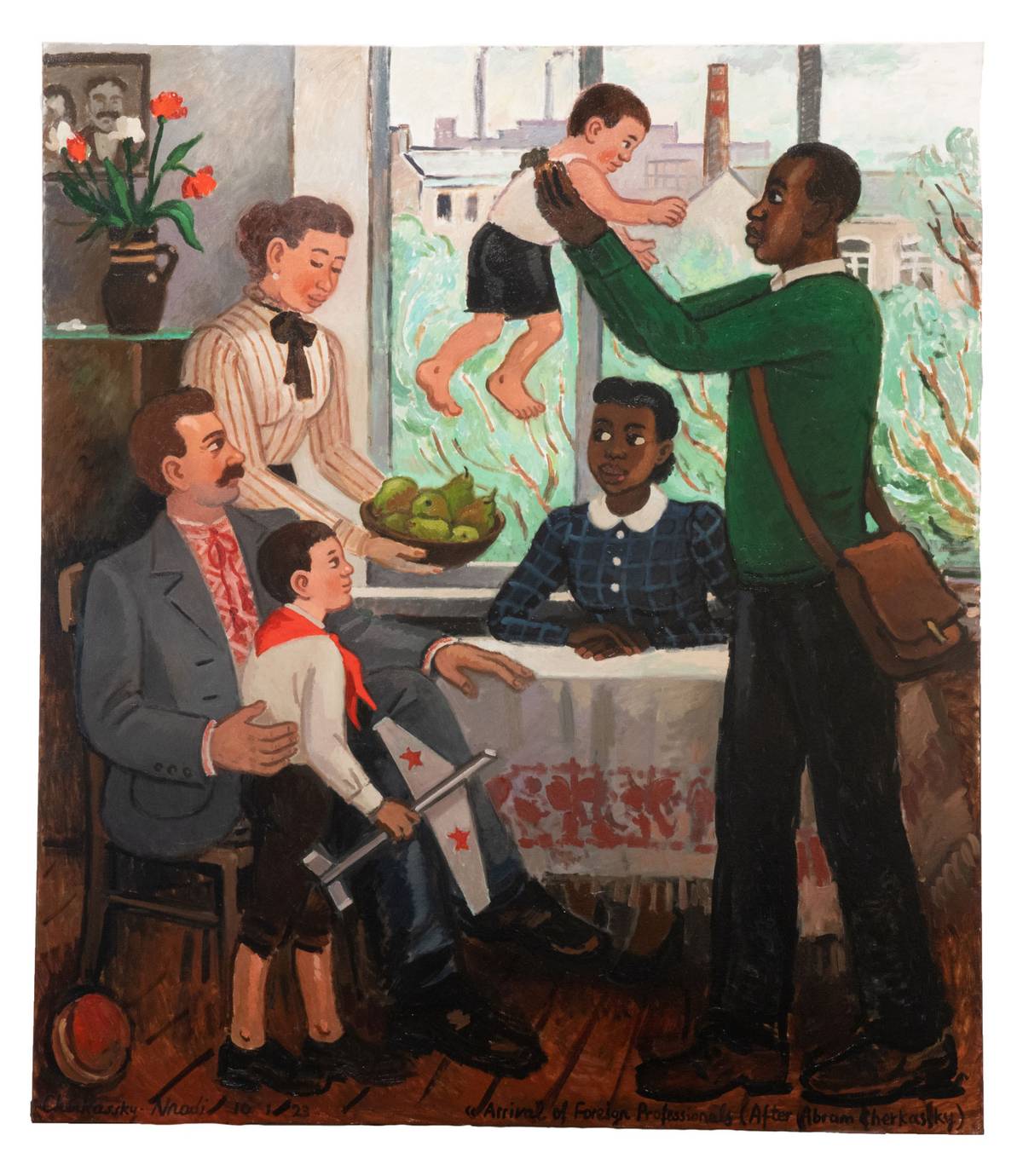

Her paternal grandfather, the architect, was a party member, like his brother, the socialist realist painter Abram Cherkassky, whose 1932 painting “Arrival of Foreign Professionals” was the impetus for Zoya’s recent painting of the same title and provided the name for her show. The figures in Abram Cherkassky’s composition are painted with the same color palette and have the same sculpturally elongated qualities you see in American WPA public art of the same period. His painting is mural-size, roughly 6 feet by 6 feet. A small photo of it, at the Fort Gansevoort Gallery, showed a happy Soviet family as they entertain cheerful, dark-skinned guests. The ruddy hostess offers a bowl of fruit, while the tall Black visitor affectionately lifts a young Soviet child high in the air. Outside the window, lush foliage blooms abundantly and industrial smoke billows from factory chimneys. The painting is both an idyll of international brotherhood and a relic of the time of the Potemkin villages, when the Soviets invited Africans and African Americans with industrial skills to help “build the future,” while concealing the catastrophe of mass starvation caused by collectivization.

Zoya hadn’t known about this particular painting by her great-uncle until someone sent her a link to it on Facebook. When she saw it she said, “that’s my family.” What she meant was that her husband in Israel was living in a reverse universe from the one depicted in the idyll. As she said to me, “African workers don’t come to Europe or Israel to have good jobs. Usually they have the worst jobs.” In the Soviet Union, in that unsustainable moment during the early 1930s, it was the opposite, they were welcomed and privileged.

About two months before the war in Ukraine, Abram Cherkassky’s painting was part of an exhibition in Kyiv and Zoya flew out to view it. She explained, “It was important for me to see it in real life. Because it’s a chromatic surface, it’s hard to make a good photo. But this whole new show is based on images I’d been collecting since I met my husband. Once in a while I made a drawing or painting relating to it and I knew that one day it would be a show. I was just waiting for the right moment. Seeing the painting by my great-uncle gave me a push to bring it all together.”

In Zoya’s reinterpretation of her great-uncle’s painting, the composition is looser and lighter. She shows more humor, giving the Soviet host a bushy moustache and whimsically embroidered shirt. Even though the faces seem hastily drawn as in cartoons, the eyes are extremely expressive. When I pointed out that the themes of the show, the failures of colonialism and the cruelties of racism, are troubling but her work is structurally expert and often beautiful, she answered, “Before everything else, I’m a painter. And when I do a painting I’m purposeful that it is painting. But I have this realistic subject, so, of course there’s also the storytelling part of it which can be dark or more tough, you know, sometimes.”

I mentioned how her shows not only tell stories but actually seem like fully conceived graphic novels.

“Often people ask me if I’m interested in comics,” she said. “There were no comics in the Soviet Union but there was a huge culture of cartoons, in which an image tells everything in one picture. I was really a fan of those things. There were two magazines, Crocodile (in Russian, Krokodil) and Pepper (in Ukrainian, Perets). I was buying both of them and, of course, I’m influenced. This is what my paintings are, they are storytelling, everything brought together, into a single image. Usually, the title is important, too. That’s how those cartoons were: the image with the title underneath it. This is the reason I include the writing on the front of my paintings.”

I asked about Art Spiegelman and she said, “Yes, of course. I love his work and I have his books but I think my most important influences happened when I was in the Soviet Union,” she said. “I think I’m sort of a Soviet painter. When I came to Israel I didn’t know about the existence of contemporary art or things like that and I was curious, I was very open. After all, I was 14, so everything new was interesting to me. But I think the core, until now, is the art school in Kyiv.”

I wondered what she took away from socialist realism, so often denigrated in the West. “You know,” she said, “it has millions of faces, this socialist realism. The stigma about it came from the portraits of Stalin and party leaders, but it’s not really like that—there are many different streams in socialist realism, some of them are very interesting. The most important influence of my Soviet art school was that Soviet art is about storytelling. This is what we were taught to do. We had tasks, like compositions, you know, ‘Tell us what you did during the summer.’”

When I asked if one part of the process—sketching or painting—was more satisfying than the other, she answered: “It’s hard to compare because they’re different and different types of pleasure. But both of them are pleasures. Yes, it’s like asking what is better, food or sex?”

I went on to ask what the drawing process provided.

“First of all, my paintings are large and I cannot approach them directly,” she replied. “I also do a lot of multifigured compositions so when I do drawings I call it detangled because I have to place all the people; let’s say I have seven people, I have to place them in a way that they form a good choreography together. So, I find that in drawing and when it’s ‘detangled’ I can transfer it into color.”

“So, when you make that transfer, the color becomes a more important aspect for you?”

©Zoya Cherkassky, courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort

“I think the color is very intuitive for me. Usually, it depends on the place I’m painting. When I paint the Soviet Union, for instance, it will be one scale of colors and when I paint Nigeria it will be something totally different. So, usually, the place dictates the colors.”

I asked her to talk about “Party at the Dorms,” one of my favorite paintings in the exhibit, which shows African students and Soviet college girls in a dormitory for international students. The African students, most probably from privileged backgrounds, are dressed in old-fashioned collared shirts and sleeveless sweaters. To the girls, they must have seemed exotic and dignified, much like the figures in Abram Cherkassky’s painting. The narrative scene is anchored with 1980s details that Zoya has lovingly documented. The Soviet-era armoire or movable closet, the turntable for a stereo system, girls dressed in Adidas-knockoff racing pants, leopard paw prints, and vintage party dresses with lace tights—all the paraphernalia marking the end of the Soviet era. But at the center you see the “foreign professionals” who are making the party fun.

“It’s my favorite, too,” Zoya said. “It’s not my memory, but my older sister’s, she went to the university in Kyiv. Although she wasn’t living in the dorms, she went to parties there, in the dorms for international students.I like the details of the ’80s in the Soviet Union because things were still very Soviet, nobody went abroad, for instance. But what they called ‘the rotten breath of the West’ had already penetrated the Iron Curtain. It was a time of big hopes but also naivety, because ‘out there, there’s a paradise,’ you know? I’ve collected a lot of footage from this time,” she said. “I think I’ve watched every possible Soviet movie from the ’80s, even the worst ones. Also, there are a lot of communities on Facebook that post private photos from this time, so when I wanted to paint the dorms I found a lot of images. I wasn’t there, but I can imagine what it looked like and, of course, my sister was my consultant on this painting.”

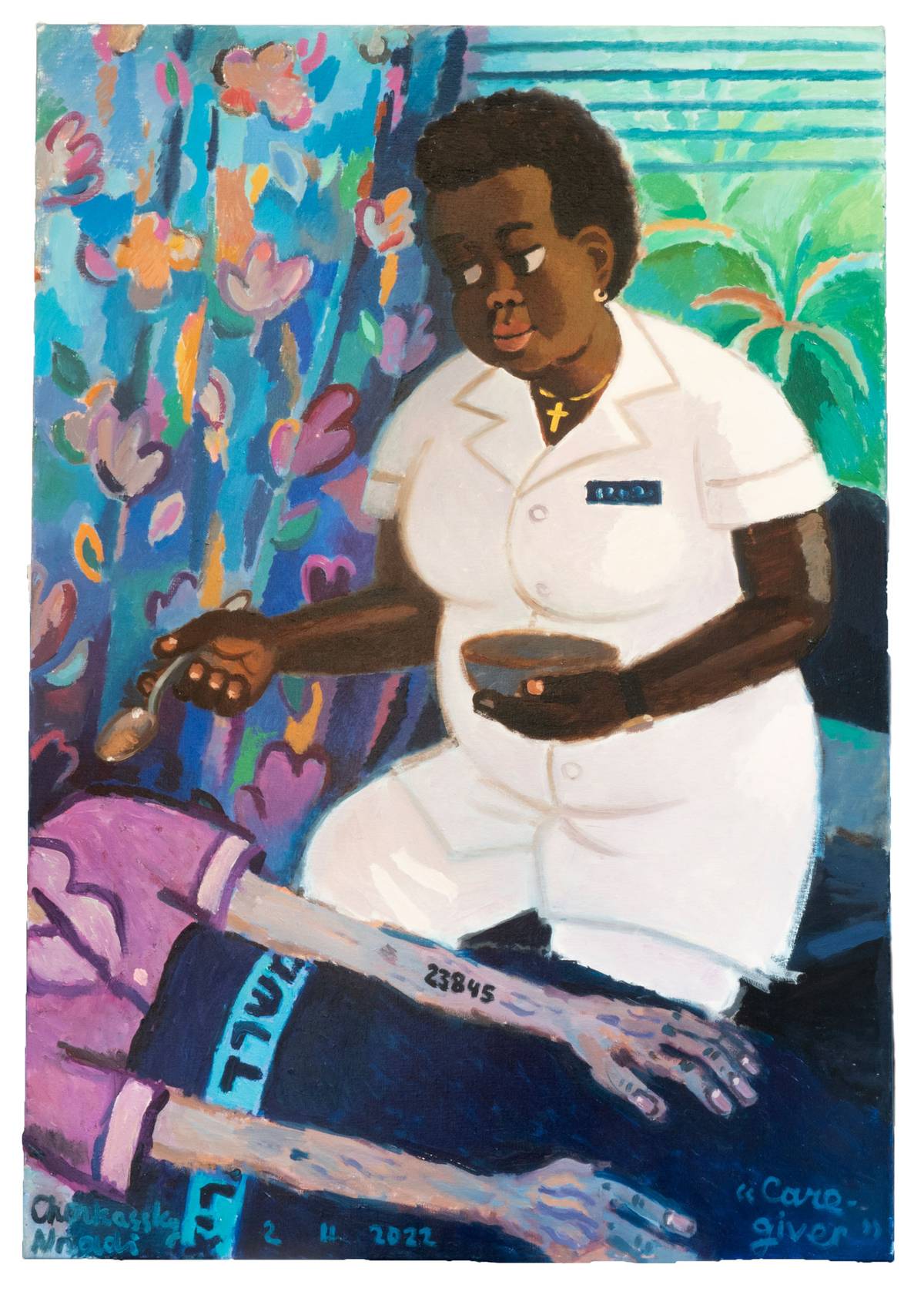

In another, more controversial painting, “Caregiver,” Zoya highlights something like a reverse variant: an African woman in Israel who has taken on a low-esteem job as a nursing aide. Dressed in a white uniform and wearing a necklace with a gold cross, a caretaker commands the center of the compositional space, a bowl in one hand and a spoon in the other. You can assume she’s been feeding an elderly woman who lies on her back at the bottom of the picture plane. The old woman’s head and face have been totally cropped off and all we can see is a portion of her pink blouse, some kind of bed cover, and her two bluish arms, the left one showing an Auschwitz tattoo.

I asked Zoya if she was aware that some people would be disturbed by the way she has reduced the old woman to her history in a concentration camp.

©Zoya Cherkassky, courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort

“I did it purposefully, of course. Now there aren’t many Holocaust survivors left and many of them are in nursing homes. My friend Lucy who is the inspiration for almost all the female figures in this show, she used to work in such a place. I wanted to bring two things together. This Holocaust survivor, now she’s old and she’s being fed with a spoon. She’s helpless, just a body, in her old age. And this cruelty is a repetition of what the Nazis did to her, they erased her identity and left her just as a number. But there’s another tragedy here, you know. The forces that cause people like my husband or Lucy to leave their home and to go to places where they’re not liked, they take these miserable jobs and send money home while they experience racism on a daily basis … I know I work a lot with stereotypes. So sometimes, well, sometimes people get offended because they take it directly as an offence—but, for me, sometimes to talk about a stereotype, I have to exaggerate, to bring it to the grotesque. This is what evokes a discussion.”

I say, “You’ve often played a combatant role in the art world. Does it feel painful to do that?”

“Yes, it hurts me. You know, during the past five or six years, I’ve wanted to do a totally escapist show, something like beautiful women in a park, something like that, nymphs playing in the woods. But every time I begin sketches, something happens, like the war in Ukraine or corona. I do something like two sketches and then something happens. I really want to be capable of doing this …”

“Art for art’s sake,” I finished her thought.

I asked if it takes up a lot of energy to be a political lightning rod.

“But it also gives a lot of energy …” she said.

Thinking about the heroic quality of her work, I say, “The courage it takes to be a combatant—I assume that’s also connected to the energy you put into your art. Are the two things interlinked?”

“Yes, of course, I think there’s a lot of anger in my art.”

“Was that always the case?”

“Yes, you know when I was a child and my mom was angry with me, I’d say to my mom, ‘How do you know, maybe I’ll grow up and be like Lenin?’ There were always the examples of hero-tyrants … you know, I always wanted to be one.”

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.