A Class of Their Own

Ultra-Orthodox women take up Talmud study

“I am not a rebellious girl by nature,” said Devorah Silberstein. “I’m doing the most traditional thing a woman can do: I’m trying to be more frum.” And yet, she’s doing something most ultra-Orthodox women have not: advanced Talmud study.

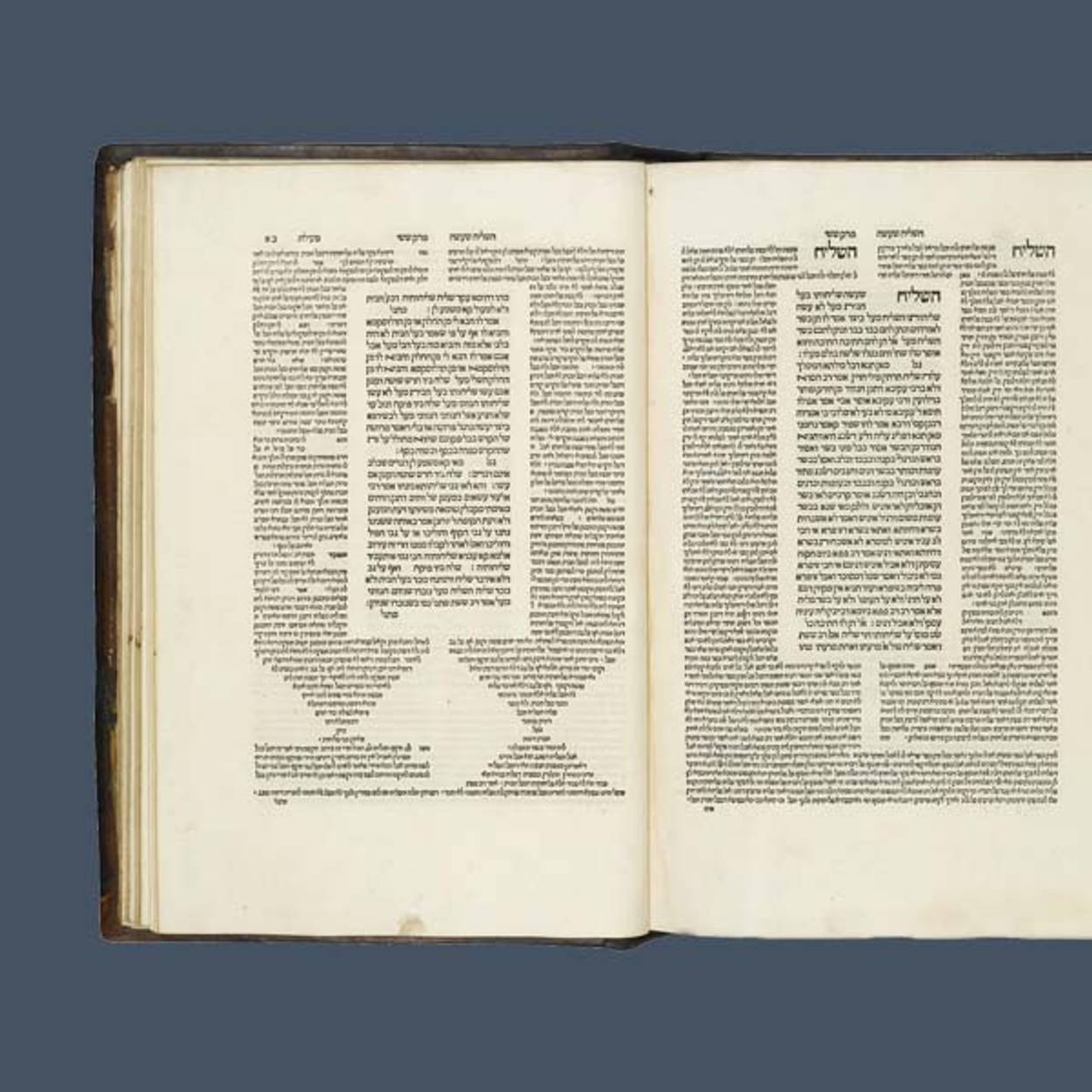

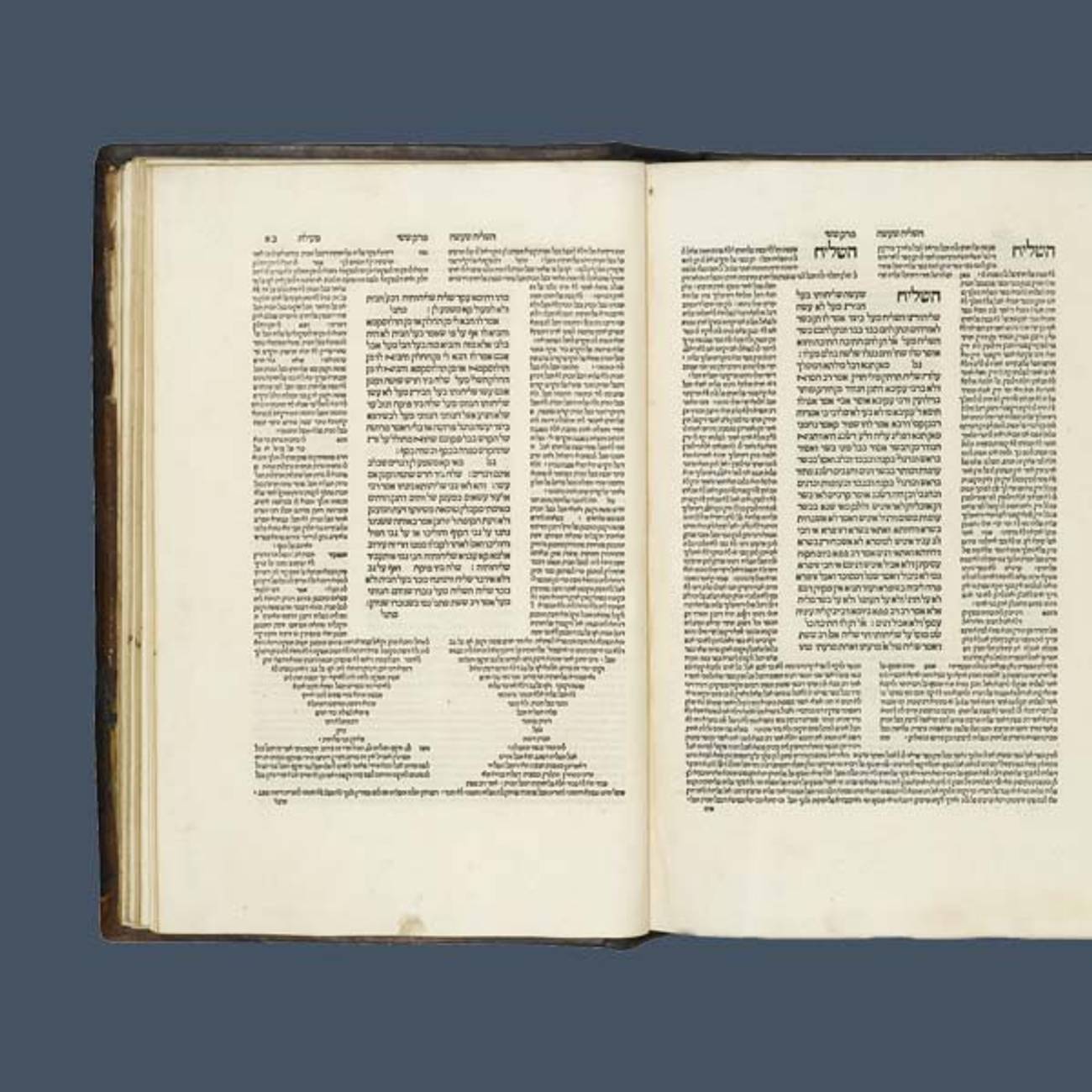

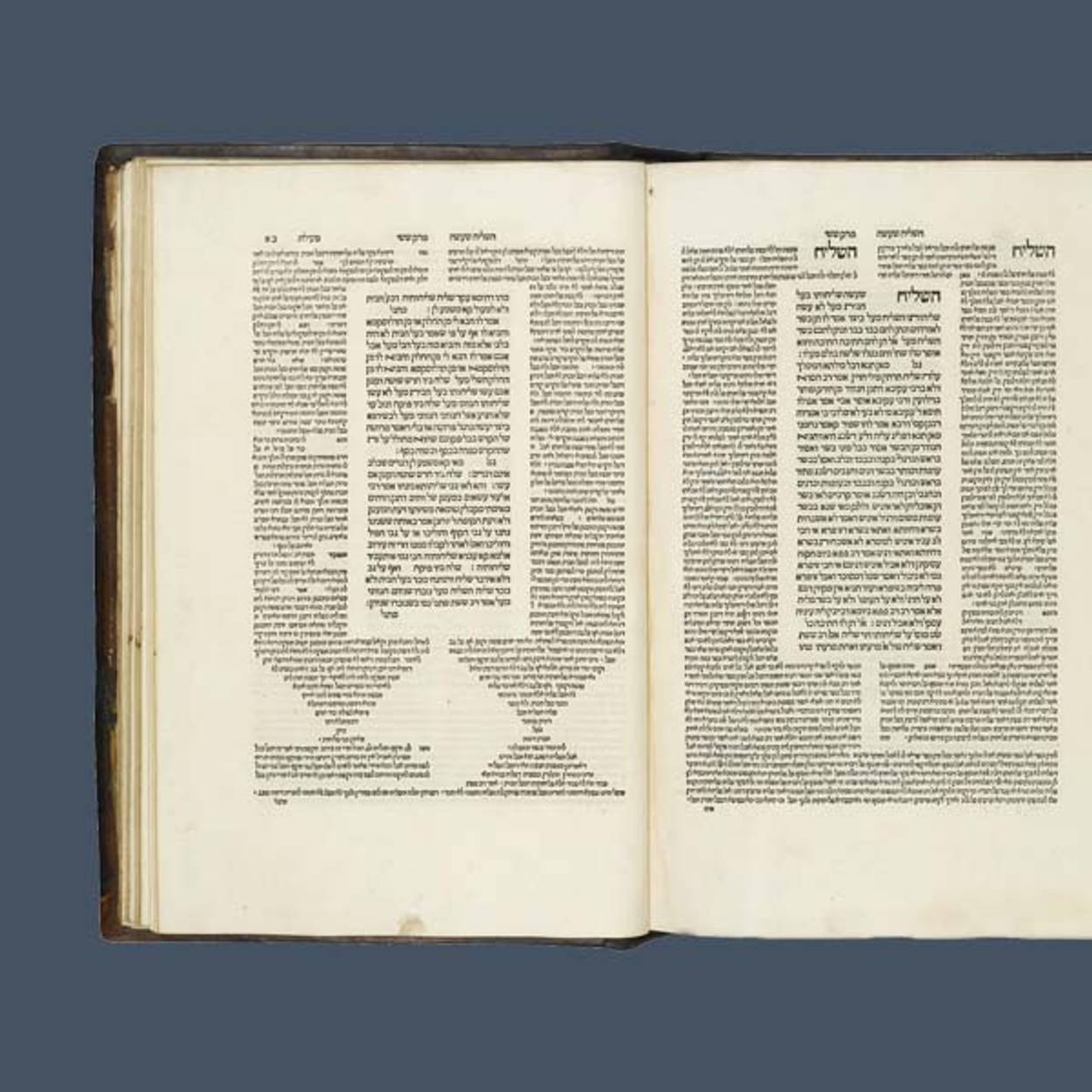

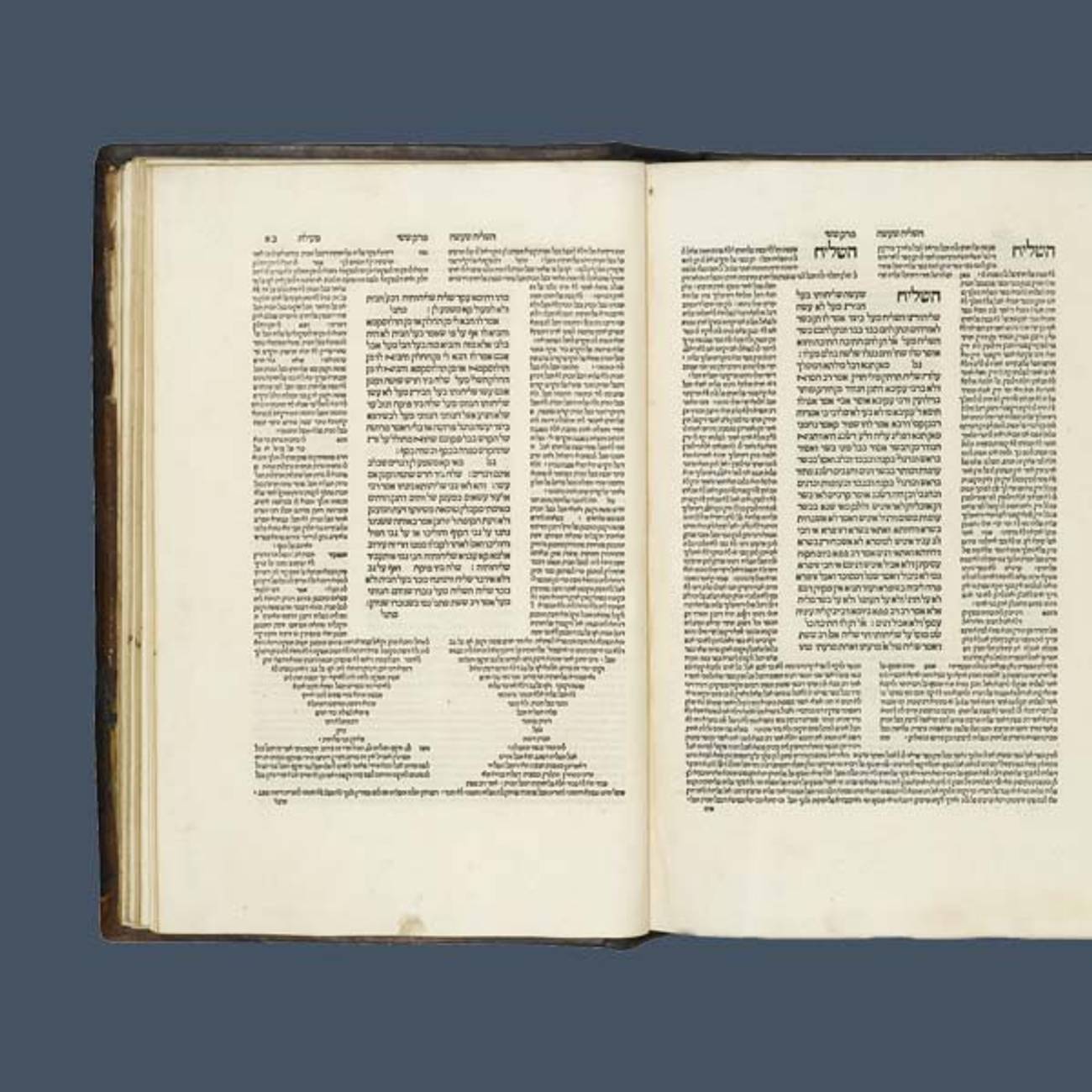

Silberstein, 22, is part of a growing movement of women in Haredi communities who are confronting women’s illiteracy about fundamental Jewish texts and the gendered inequality in serious text-based learning opportunities, specifically of Talmud. These ultra-Orthodox women are seeking to overhaul the average Haredi girl’s education, with its steady diet of biblical subjects, but very little study, if any, of Gemara or Mishna, the two sets of writings that constitute the Talmud. Unlike the boys’ yeshiva school system, which is founded on intimate study of Talmud, female Haredi education entirely excludes it.

“People say that women don’t need it,” said Silberstein. “But it’s a huge part of my Judaism, and you can so tangibly see the lack when you look at the frum [religious] community. You see the hole in our education, because we don’t teach women Halacha [Jewish law] from the sources.”

Silberstein and her compatriots view themselves as the intellectual descendants of the rare female scholars peppered throughout Jewish history, from Beruriah, the famed Talmudic master quoted in the Gemara, to Edel—the daughter of Hasidism’s founder, the Baal Shem Tov, who was so knowledgeable in Oral Torah that her father’s followers turned to her for guidance.

These women believe their communities are in desperate need of not one or two learned women every other generation, but legions of them, who can teach girls Talmud starting from elementary school. They feel this educational overhaul is crucial to imbue Haredi girls with a true, deep understanding of their own Judaism. Without personal knowledge of Gemara and Mishna, the texts shaping every moment of an Orthodox Jewish life, they believe quotidian rituals and practices are done by rote, but without appreciation for their origins, development, and purpose. They see a discordant reality where the writings forming the ancient roots of Rabbinic Judaism are foreign lands to the women living by their strictures. They watch from outside as the learners of Talmud are inducted into a masculine fellowship of study with their contemporaries and the rabbinic figures animated in the Talmud’s pages. Communities are cloven in two, with men ingrained with a near-reflexive comprehension of the famed Talmudic language and analytic method and women ignorant of the fundamental texts upon which their lives depend.

To rectify this, they have organized around a renegade learning program rooted in tradition called the Batsheva Learning Center, founded in 2015 by Silberstein’s older sister, Hadassah Silberstein-Shemtov. Batsheva’s model centers around beginner and advanced courses in Talmud for post-high school women taught online and in person at various locations—private homes, synagogues—throughout Brooklyn and Los Angeles; these two-month-long classes are offered three times year, with one course taught in autumn, spring, and summer. From 19-year-olds fresh out of seminary to grandmothers in their 60s, women are paired up chavrusa-style to learn themed portions of the Oral Torah. Courses tend to focus on issues women might find particularly resonant; one of Batsheva’s most popular classes studies the laws of niddah, or family purity. Three new classes are developed each year. For instance, Silberstein is currently preparing a course on the laws of Shabbat that Batsheva will offer in the autumn, after Silberstein completes the Yeshiva University Graduate Program in Advanced Talmudic Studies (a program she will leave without receiving its master’s degree, as she has no bachelor’s degree, never having attended college).

Batsheva classes study Talmudic texts directly but are buttressed by proprietary coursebooks that include guiding questions, translations of difficult terms, and a reference list of abbreviations. These secondary sources are intentionally designed to give a neophyte the tools needed to approach the text directly and methodically become proficient. The coursebooks can also be bought separately from the Batsheva classes, to assist in an independent study of the topic.

Another core part of Batsheva programming are weekly learning classes on the Torah portion at Brooklyn-based gatherings, which have recently restarted for the first time since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Dozens of women attend each week on a regular study schedule.

Batsheva’s programming has also expanded into offering a chidon-style program—or Torah-study championship—for high school-age students, where girls are challenged to learn one book of Oral Torah on their own. This program will soon be offered for middle schoolers, as well.

Currently, Batsheva is planning for its audacious next step: fundraising to establish a beis midrash in Crown Heights, where women will study Torah full-time. They hope to open their doors this autumn.

“Across the spectrum of religious communities, it has become normal for women to get advanced degrees and have professional careers, but for them to invest time in learning Gemara is not considered necessary in any way,” said Silberstein-Shemtov, whose intense passion for women’s Torah study is obvious as she speaks rapidly about it as a crucial expression of a woman’s religious service to God. “This creates a huge divide in a woman’s life, where her sophisticated secular life is much more engaging intellectually and emotionally, and her Judaism remains at a juvenile level. If the frum community’s goal is to raise generations of women and girls who are engaged and passionate about their Judaism, we need to change our attitude toward women’s learning.”

Silberstein-Shemtov, 29, is uniquely poised to lead this campaign. Raised out-of-town—i.e., beyond the cloisters of Haredi Brooklyn—she was home-schooled in her early years by a brilliant mother. There, she was exposed to Oral Torah, including Mishna. After high school, she attended an elite Israeli seminary where she first learned Talmud rigorously. When she returned to the United States, she was frustrated by the absence of infrastructure to continue her studies. She decided to do something about it.

But effecting change in Haredi education requires rabbinic approbation, and community rabbis have generally nestled into their tactical position as enemies of the notion of women studying Talmud. Interpreting Talmudic instructions regarding women’s roles within organized Jewish life, some rabbis read a biological female disinclination toward Talmudic learning; others take the efficient view that learning is too great a time commitment for both parents to engage in equally, so mothers drew the child-rearing straw.

Silberstein-Shemtov believes that as a member of the Chabad community, she is exceptionally empowered to attack this issue. Unlike other Haredi streams, Chabad’s leader, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson—popularly known simply as the Rebbe—was outspoken in his lifetime about the need for women to study all of the Oral Torah, including Talmud.

Silberstein-Shemtov cites as Batsheva’s ideological backbone a little-known 1990 directive by the Rebbe where he announced in a sicha, or public talk, at a Shabbat farbrengen (gathering) not only the permissibility but the religious obligation of all Jewish women to learn Talmud. Rather than reading women’s traditional roles as making them unsuited to serious study, the Rebbe’s position was that a woman is naturally disposed to the activity. The Rebbe’s interpretive arguments emerged from sociological, historical, pragmatic, and messianic concerns, and rested on classical biblical and Talmudic texts, but analyzed and presented in a revolutionary manner.

First, the Rebbe repackaged the conventional Jewish role of women as akeres habayis, or foundation of the home. To function as a successful akeres habayis, responsible for shaping the home’s environment and raising a family infused with Jewish values, the Rebbe said a woman requires a strong understanding of those values derived from her own learning. Second, the Rebbe characterized women as vibrant thinkers whose Jewish souls cannot be nourished by secular learning; rather, she can and must learn Torah to develop her relationship with God. Third, the Rebbe described the advent of widespread women’s learning as a necessary step in the perfection of the world in preparation for the messianic era; the Rebbe did not merely accept women’s learning as an unavoidable development of a modern society, but reframed it as a critical step in the spiritual elevation of the world.

“[T]herefore not only is it permitted for them [women] to learn the Oral Torah, but more than this … they need to learn the Oral Torah, not only to learn the verses of laws without their reasons, but also the reasons for the laws, even the complicated back and forth of the [Talmud], since it is the nature of a person (man or woman) that they have greater desire for and pleasure in this type of learning,” said the Rebbe.

Chava Green, a doctoral student at Emory University’s Graduate Division of Religion whose research focuses on Hasidic feminist ethnography, reads the Rebbe’s position as a radical statement that “women are intellectual people.” She views it as a particularistic form of “Hasidic feminism.” She adds that, given the Rebbe’s unequivocal stance, the frum world must provide intensive learning options to women, because without them, “it means we don’t take women’s intellect seriously.”

Yet, Silberstein-Shemtov acknowledges that the Rebbe’s position on this is long-ignored even within Chabad itself. According to Green’s research, outside of Batsheva, Chabad women and girls are still largely not taught Talmud. Silberstein-Shemtov says school administrators’ common excuse for this egregious failure is that students are not interested.

This negligence is especially strange, as for Chabad, the Rebbe’s view is the only rabbinic perspective that holds weight; there are no competing rabbinic interpretations to navigate. If the Rebbe instructed that women should learn Talmud, the Rebbe’s followers must institute that.

Shlomo Yaffe, rabbi of Congregation Bnei Torah and a board member at Batsheva Learning Center, recognizes that the glaring lapse results from school administrators’ discomfort with actualizing the Rebbe’s guidance. “The Rebbe was always shaking things up,” said Yaffe, explaining that there are other innovations within Jewish life and practice rolled out by the Rebbe that took time to become widely institutionalized, including the notion of shlichus—i.e., the Chabad emissaries posted around the world who are now synonymous with the movement.

Yaffe says the Rebbe talked about the importance of women’s learning multiple times throughout his 43-year leadership, but that the Hasidim generally tabled making these drastic changes in favor of focusing on other efforts.

Rebbetzin Rivkah Slonim, educational director at Binghamton University’s Rohr Chabad Center for Jewish Student Life and an early supporter of Batsheva, recalls another sicha, delivered on a Shabbat in 1986, where the Rebbe reinterpreted the Torah’s presentation of the outgoing nature of Patriarch Jacob and Matriarch Leah’s daughter Dinah as an essential, vital element of what it is to be a Jewish woman. This was in stark contrast to the traditional reading of Dinah as bearing the glaring flaw of immodesty.

“Because of what was happening in the larger Jewish world at the time, this sicha made such waves,” said Slonim, explaining that the sicha was presented only about a decade after the Reform movement had ordained its first female rabbi in 1973. “The Rebbe’s take on Dinah was a seismic shock.”

According to Yaffe and Slonim, no one in Chabad establishment life would counter the Rebbe’s view. But that doesn’t mean the community was mentally prepared to upend centuries of gender norms. Both agreed that years needed to pass for the community to become acclimated to the idea, and that a campaign for women’s learning has awaited someone to take it on as their personal project. In their view, Silberstein-Shemtov has emerged as that crusader.

“Hadassah has made it her baby, and it has blossomed and is having tremendous success,” Yaffe said.

Silberstein-Shemtov recalls that whatever progress she has achieved has come only after numerous failures. Initially, Silberstein-Shemtov set out to create a place for hyperadvanced learning, the kind of institution she would have liked to attend. She eagerly opened her proverbial doors, and no one showed up. It turns out the average Haredi woman lacks the necessary basic skills, especially with respect to Talmud study. Silberstein-Shemtov regrouped—many times—until she identified the critical failures of the Haredi education system and an effective stratagem for fixing them. Batsheva’s focus became constructing curriculum to guide a neophyte to becoming proficient at learning Oral Torah in-depth and inside the text.

“It’s about basic literacy,” said Chana Silberstein, the educational director at Chabad of Ithaca who holds a doctorate in educational psychology from Cornell University, and Silberstein-Shemtov’s mother and one of her first Mishna teachers. “The benchmark of any education is the ability to read, so a basic Jewish education requires that you be able to engage with Torah. It does not mean you need to personally become a master of Gemara. But in a family where Torah is important and learning is important, you as a mother, sister, daughter must be able to participate.”

Batsheva’s course books include introductions on the development of Jewish law, explaining how to contextualize different legal movements and interpretations throughout Jewish history. The books aid the new Gemara-learner through the Talmud’s textual mysteries.

Slonim approves of Batsheva’s text-based approach as an imperative departure from the inspirational, self-help seminar that is the dominant format for Haredi women’s learning. She urges women to reject “chewed up and regurgitated Torah.” She says Haredi women have to stop treating Talmud as a “boys’ club,” alter their self-perception, and embrace that they are fully capable of intensive Torah study.

These women are echoing arguments Sara Schenirer made for girls requiring a rudimentary Torah knowledge when she founded the Bais Yaakov schools in 1917. Schenirer slapped awake the intellectual soul of the average Orthodox Jewish woman who could not even read Hebrew, pulling her out “from her long, lethargic sleep,” as Schenirer put it. Schenirer was particularly concerned with the breakdown of the Jewish home, with unhappy marriages being arranged between secularly educated, cultured Jewish women and yeshiva-educated men, and a significant percentage of Jewish women breaking faith entirely. Schenirer identified Jewish education for girls as an antidote to this crisis. Bais Yaakov began as a grassroots movement, with handfuls of girls attending classes in Schenirer’s tailor shop. It eventually morphed into establishment institutions that remain the dominant model for Orthodox Jewish girls’ education.

Silberstein-Shemtov hopes to stimulate a similar sea change in the frum community by normalizing women’s regular, intensive learning of Talmud. Though Jewish women today have far greater access to Torah study than they did a century ago, the inequality remains potent. As her mother put it, “On one side of the Shabbos table, women are exchanging recipes, and on the other, the men are exchanging learning.” The women behind Batsheva passionately believe that for Haredi communities to adequately confront the challenges of 21st-century life, and build thriving family units, girls need to be familiar with more than the weekly Torah portion. In Silberstein-Shemtov’s mind, many of the growing difficulties Orthodox girls’ educators talk about—crises of Jewish observance and spiritual curiosity in a world increasingly hostile to religion—could be rectified if administrators equipped girls with the tools to learn the answers Judaism offers to the questions that emerge as a natural part of maturing. Batsheva challenges administrators to arm their students with the ability to flourish, with learning as the critical modality of living a meaningful life as a Jewish woman.

For now, like Schenirer’s early days, Silberstein-Shemtov works on the outside, demonstrating demand and providing supply. Batsheva runs Talmud courses throughout the year, and last summer piloted a “Mishna for Moms” course geared specifically toward provisioning mothers with the tools they need to be able to converse with their children (read, sons) about what they’re taught in yeshiva. Batsheva intends to introduce online Gemara classes for high schoolers and Mishna for middle schoolers next year. Meanwhile, the forthcoming Beis Midrash is, as Silberstein-Shemtov describes it, the truest expression of the vision she first had when she began Batsheva. The beis midrash will begin as a part-time study center, but Silberstein-Shemtov intends for it to evolve into a full-time, three-year certification program for Gemara teachers. The beis midrash will not replace Batsheva’s extensive other programming; rather, Silberstein-Shemtov intends for it to be the place for those women who would like to learn with intense commitment and consistency and become expert educators in the field.

While ambitious, these plans may succeed. Batsheva has bloomed in the last seven years simply over social media and by word-of-mouth, becoming the institution young Chabad women know to turn to for assistance when hoping to breech the walls encasing Gemara. Nearly 60 women participate in each run of Batsheva’s most popular Gemara courses, and over 100 Chabad high school girls compete in the international chidon, which Batsheva aims to expand to non-Chabad schools soon.

Batsheva has a burgeoning influence in other Haredi communities, too. The COVID-19 pandemic brought Batsheva’s programming online for the first time, resulting in attendance by young women from other Haredi communities. In-person classes have also been launched in cities outside of New York, including Los Angeles, where Silberstein-Shemtov lives. She says out-of-town communities are better integrated across Haredi streams, allowing Batsheva’s soft marketing to naturally permeate beyond Chabad.

Silberstein-Shemtov’s new dream? “That the most frum, Hasidishe woman from Boro Park can walk into our classes and feel comfortable—and learn.”

Rachel Frommer is an attorney, writer, and Tikvah Fund Krauthammer Fellow in New York.