How To Solve Disputes Between Schools of Jewish Thought? In Private, or Not at All.

At what point does a disagreement between groups of Jews become a point of religious principle, which cannot be compromised?

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

As a teenager, I spent a couple of summers at Camp Ramah, the camp of the Conservative movement. Most of the campers were, like me, raised in Conservative synagogues, but one summer there was a boy who had decided to become much more frum than his parents. As a result, he refused to eat the food prepared in the camp dining hall, since he had doubts about its standard of kashrut. As I recall, this act of teenage rebellion—and even then that’s how it seemed to me, though it was a rebellion in the direction of extra discipline rather than misbehavior—created serious headaches for the camp counselors, who didn’t want the boy to spend a month subsisting on packaged bread and peanut butter. The food, they insisted, had been declared kosher by the camp’s own rabbi—wasn’t that enough? But the camper insisted it wasn’t: He wouldn’t eat the food unless his own, Orthodox rabbi had given it his seal of approval.

This was one of my early exposures to the issue of Jewish denominational strife, and the memory resurfaced during this week’s Daf Yomi reading. One of the most frequent divisions mentioned in the Talmud is the one between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel—the schools founded by the great pair of rabbis who lived in the first century B.C.E. These groups disagreed on many matters of Jewish law: For instance, Beit Shammai believed that on Hanukkah we should begin by lighting eight candles on the first night and then take one away on each subsequent night, while Beit Hillel believed in starting with one candle and then adding more. Back in Tractate Eruvin, we read about how a bat kol, a divine voice, pronounced that while both Hillel and Shammai’s opinions were valid—“these and these are the words of the living God”—the law follows the opinion of Hillel (with a few specific exceptions).

So far in Tractate Yevamot, we have been learning the law that if a man is forbidden to take a woman in levirate marriage, he is also forbidden to marry her “rival wife.” Say, for instance, that two brothers marry two sisters, and one of the brothers dies. The surviving brother cannot marry the widow, because she is his wife’s sister. Now imagine that the dead brother also left a second widow (remember that polygamy was acceptable in Talmudic times). Even though he is not related to her, the surviving brother cannot marry her either, because she is his wife’s sister’s rival wife.

In Yevamot 13a, however, we learn that this principle was a matter of dispute between Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai. Beit Hillel ruled that rival wives of forbidden widows were exempt from levirate marriage, and that is how the law stands; but Beit Shammai permitted marriage to rival wives. They based their ruling on a reading of Deuteronomy 25:5, which states: “The wife of the dead man shall not be married outside of the family to one not of his kin.” “And the Merciful One states: ‘Shall not be,’ ” the Gemara explains; this is an absolute commandment, and it applies to all of the dead man’s wives.

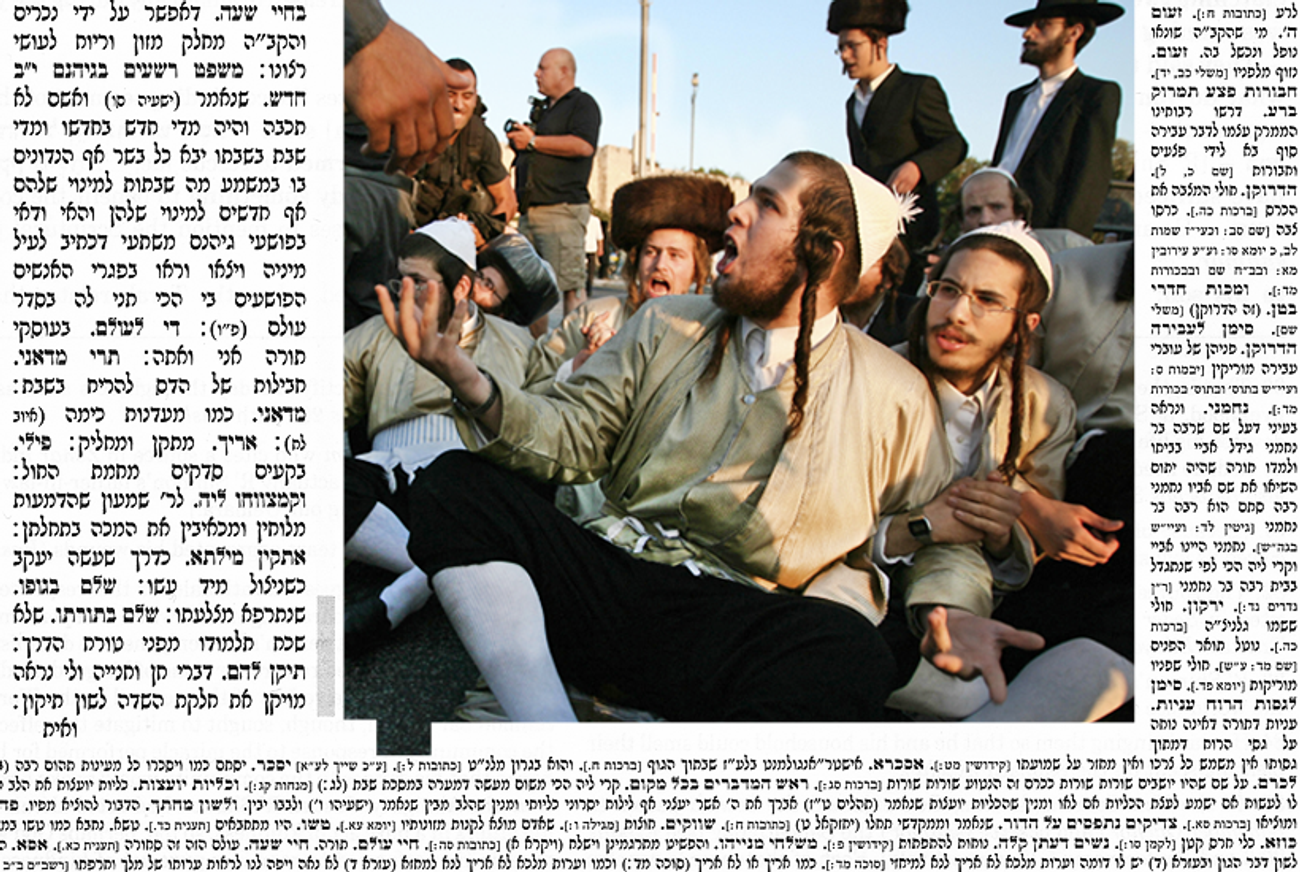

This disagreement, however, raises a question about how the different opinions of Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai were put into practice. If the law follows Beit Hillel, does that mean that Beit Shammai set aside their own opinion and deferred to their rivals? Or did Beit Shammai actually live by a different law than Beit Hillel? And if so, didn’t this entail splitting the Jewish community into two different factions, something that is itself forbidden? Reish Lakish deduces this prohibition against factionalism from a creative interpretation of a verse from Deuteronomy, which instructs, “You shall not cut yourselves.” In context, this literally means that Jews cannot cut their flesh in mourning, as was apparently the practice of other, pagan tribes. But Reish Lakish takes the word “cut yourselves” and links it to the related word “factions”: What this really means, he says, is “Do not become numerous factions.”

Did Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel constitute factions in this sense? Were their disagreements theoretical or did they affect practice as well? At first, the Gemara tries to show that even if they followed different customs, these differences were not so important as to visibly separate the two schools. For instance, as we learned in Tractate Pesachim, Beit Shammai forbids Jews to work on the night of the 13th of Nisan, the day before Passover begins, while Beit Hillel permits it. But as Reish Lakish points out, this is not a dramatic, visible difference, since if an adherent of Beit Shammai stops working, an adherent of Beit Hillel might assume it was not for doctrinal reasons but simply because he was done with his work.

When it comes to levirate marriage, however, there is much more at stake. Beit Shammai permits the marriage to a forbidden widow’s rival wife, which Beit Hillel forbids. Say a man marries such a rival wife and produces a child with her. According to Beit Hillel, such a child would be a mamzer—a word often translated as “bastard” or “illegitimate,” though the Jewish legal concept does not exactly correspond to what those English words mean. Since a Jew is not permitted to marry a mamzer, the child would be forbidden in marriage to anyone who follows Beit Hillel. According to Beit Shammai, however, the child would be perfectly legitimate. What would happen, then, if a man who follows Beit Hillel marries a woman from Beit Shammai, only to find that she is, according to his own legal tradition, a mamzer? One might expect that, to avoid such a situation, the two groups would refuse to intermarry—which would be a dire form of factionalism.

Fortunately, the Gemara reassures us that this was not the case: “Beit Shammai did not refrain from marrying women from Beit Hillel, nor did Beit Hillel refrain from marrying women from Beit Shammai. This serves to teach you that they practiced affection and camaraderie between them.” Yet Rabbi Shimon adds a qualification: “They did refrain in the certain cases, but they did not refrain in the uncertain cases.” That is, if an ordinary woman from Beit Shammai was proposed in marriage, a man from Beit Hillel did not raise questions about her ancestry; he could assume that she was not a mamzer. If, however, Beit Shammai knew for certain that a woman was the child of a marriage that Beit Hillel would have forbidden, they “would notify” Beit Hillel, and the marriage was canceled. In this way, the problem of mamzerim never arose.

This settles the particular issue discussed in Yevamot, but as the Gemara goes on to explain, there were still other areas of law in which Hillel and Shammai disagreed. The rabbis want to know what rule was followed: Did Beit Shammai act according to their own opinion, or did they defer to the opinion of Beit Hillel, even though they disagreed with it? This may seem like a minor question, but in fact, as often happens in the Talmud, it leads to a major philosophical issue. At what point does a disagreement between Jews become a point of religious principle, which cannot be compromised? History shows that, when such disagreements become unbridgeable, the result can be disastrous. The fall of the Second Temple was attributed to just such internecine anger between Jews. In our own time, Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated by a Jew who believed that Rabin’s peace policy was not a subject for political disagreement but an outright sin.

The specific cases discussed in Yevamot 15a-b are not so dramatic. Shammai believed that a baby is obligated to perform the mitzvah of sitting in a sukkah from the moment it is born, while Hillel did not. When a grandson was born to Shammai, then, he “removed the mortar covering the ceiling and placed sukkah covering over the bed for the child,” so that the baby would technically be in a sukkah. Wasn’t this a public demonstration that he did follow his own opinion, while defying Hillel’s? Not necessarily, the Gemara replies: An onlooker might simply think that Shammai opened the roof “to increase the air” in the baby’s room, for the sake of ventilation.

Again, Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel disagreed about a minor point relating to the purification of utensils. To be purged of tumah, utensils had to be immersed in a ritual bath. In Jerusalem, there was a certain trough that was connected to a ritual bath, “and all the ritual purifications in Jerusalem were performed in it”: People would bring their implements and wash them in this trough, whose water came from the adjacent mikveh. However, the ritual bath and the trough were connected only by a small hole. Now, for Beit Hillel, this was fine, since they held that “a joining of ritual baths is effective if the hole” is big enough for “two fingers that can return to their place”: That is, if you can wiggle two fingers in the hole, it is sufficient.

For Beit Shammai, however, this was too small; they believed the joining of ritual baths required that the majority of the barrier between them be removed. Accordingly, Beit Shammai sent messengers to widen the opening between the trough and the ritual bath, so it would be valid according to their definition. Wasn’t this an example of Beit Shammai acting according to their own opinion of the law, rather than deferring to Beit Hillel? Again, however, the Gemara denies it. “There, anyone watching would say that he did it increase the water flow,” the rabbis observe. That is, the widening of the hole wouldn’t necessarily be taken as a legal matter; it might well be considered just a matter of convenience.

Clearly, what concerns the rabbis when it comes to factionalism is the possibility of Jews disagreeing about the Law in public. No wonder even the greatest sages hesitated to get involved in disputes between the two schools. “They asked Rabbi Yehoshua: What is the law with regard to the rival wife of a daughter? He said to them: It is a matter of dispute between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel.” But this evasive answer wasn’t enough to satisfy the questioners, who pressed him: “And in accordance with whose statement is the law? He said to them: Why are you inserting my head between two great mountains?” Getting caught between Hillel and Shammai was like being caught in a war between mountains—or, as we might say, between rock and a hard place. No wonder it took a divine voice to settle the argument between them.

***

To read Tablet’s complete archive of two years of Daf Yomi Talmud study, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.