Your Bubbe Was Not More Jewish Than You Are

The Talmud debunks the myth of declining Jewish piety

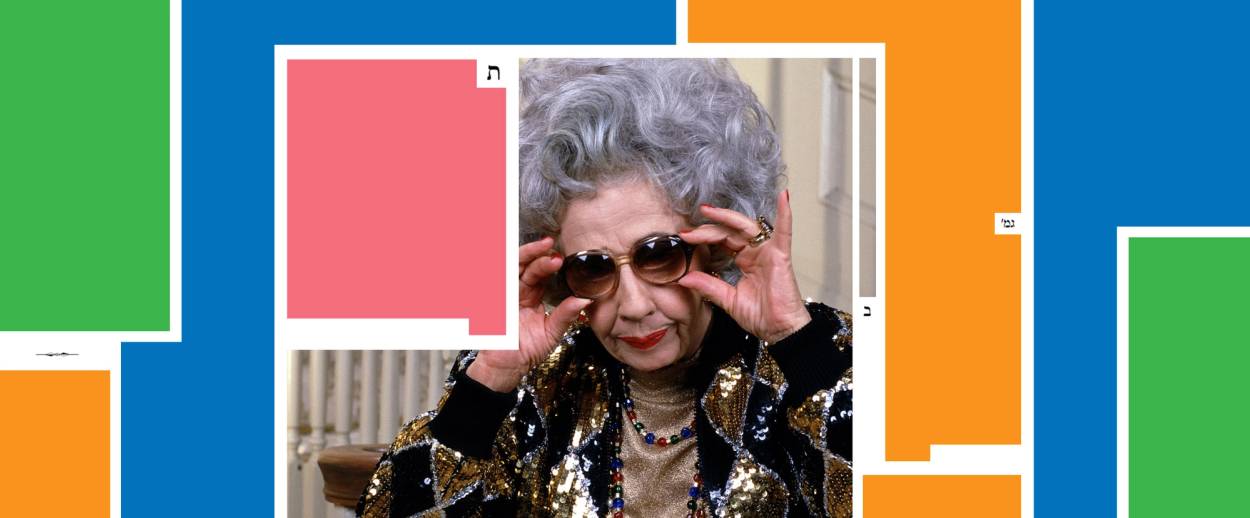

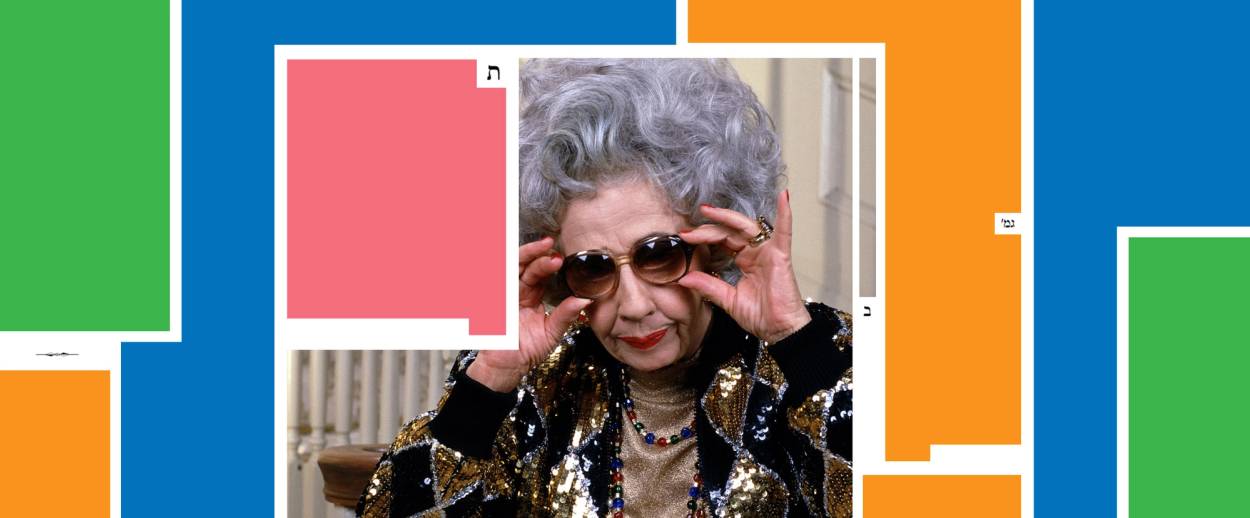

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

Reading Daf Yomi, one of the things that has most interested me is the Talmud’s picture of the Jewish society of its day. It’s easy to assume that, because the rabbis who assembled the Mishna and the Gemara were exceptionally learned and pious, the Jewish world they lived in was itself extremely devout. Surely the Jews of Palestine and Babylonia in the 1st centuries C.E. would put American Jews to shame with their Jewish knowledge and practice! Yet that is certainly not the way the rabbis of the Talmud understood their world. On the contrary, the impression they give is of a Jewish community divided between a very pious elite—the people the Talmud calls chaverim, “friends,” who took care to scrupulously follow the law—and an ignorant, unreliable mass of ordinary Jews, the am ha’aretz. What’s more, as we saw in this week’s Daf Yomi reading, the rabbis were convinced that they stood at the end of a long, irreversible decline in Jewish piety. If we think that Jews who lived centuries ago were better Jews than we are today, the Jews of centuries ago thought exactly the same thing.

The litany of spiritual decline can be found in the last chapter of Tractate Sota, which Daf Yomi readers finished this week. As we saw last week, the final chapters of Sota lose track of the ostensible subject of the tractate—the ritual of the sota, the married woman suspected of adultery—and take up a number of different subjects. The unifying thread among these topics is language: There are several biblical rituals that involve saying certain formulas, and the Talmud asks whether these formulas must be said in Hebrew, or if they can be translated for the sake of better understanding. Chapter 9 asks this question about the ritual prescribed in Deuteronomy for cases of unsolved murder. If a corpse is found in the Land of Israel and no one knows how it died, judges from the nearest city must sacrifice a heifer by breaking its neck and recite a speech in which they announce, “Our hands did not spill this blood, nor did our eyes see.” In this way they avert God’s vengeance for the murdered person. And this recitation, we learn in Sota 44b, must be in what the mishna calls lashon hakodesh, the sacred tongue, Hebrew.

Much of the chapter is devoted to analyzing this ritual. How many judges, for instance, are required to take part? Opinions range from three to nine, depending on how the verse is interpreted. What happens if the corpse is discovered, not out in the open as the Bible envisions, but hidden in a pile of stones or hanging from a tree? This question leads into a long excursus on the laws of gleaning, in which the rabbis deduce the definition of “hidden” from various situations involving sheaves of grain. And what happens if the corpse is discovered with its head severed? Do you measure the distance to the nearest city from the head or from the midsection? This question leads to a biological debate about where the center of life resides in the human body: Akiva says that “life is mainly in the nose,” since that is where we breathe, while Eliezer says “life is mainly in the navel,” since that is where we digest.

But after devoting many pages to the proper performance of “the ritual of the heifer whose neck is broken,” the mishna in Sota 47 announces that it is all purely theoretical: “From the time when murderers proliferated, the ritual of the heifer whose neck is broken was nullified.” The ritual was given to the Israelites during a distant and virtuous past, when cases of murder were so rare that they required a special remedy. But at some point, murder became so common among Jews that some men were even publicly known as murderers: “From the time when Eliezer ben Dinai came … they renamed him, Son of a murderer,” the mishna adds. As a result, it was no longer possible to discover a corpse and say truly that you didn’t know who killed it; there were now many potential suspects, and the nearest city couldn’t claim innocence. Thus the ritual was discontinued.

The same logic, the mishna goes on to explain, meant that the sota ritual, the main subject of the tractate, was also null and void. Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai, who lived around the time of the destruction of the Temple, canceled the ritual, quoting words from the prophet Hosea: “I will not punish your daughters when they commit harlotry, nor your daughters-in-law when they commit adultery.” Sexual immorality had grown so common among the Jewish people that it could no longer be singled out as a rare crime. In particular, adulterous husbands lost the right to accuse their wives of adultery.

These examples point to a diagnosis of moral and spiritual decline among the Jewish people. The Gemara goes on to elaborate zealously on this theme. “From the time when those who accept benefit from others proliferated, the laws became twisted and deeds became corrupted, and there was no comfort in the world.” Exactly who are “those who accept benefit from others”? Commentators offer different answers: To Rashi, it means those who are single-mindedly devoted to pleasure; others say it refers to judges who accept bribes from litigants.

And that’s not all. The Gemara goes on to complain about arrogant people who “draw spittle,” which seems to mean people who are excessively fastidious and snobbish about manners. Then there the “haughty people” who stopped studying Torah because they believed they had nothing more to learn; and superficial people who “look only at the face,” judging others by their appearance rather than their substance; and “those greedy for profit,” who refused to lend money to the needy; and “those with boastful hearts,” who engaged in unnecessary strife about the law so that “dispute proliferated in Israel, and the Torah became like two Torahs.” If every one of these charges seems like it could equally fit our own time, that is because the perception of decline is eternal. Everyone looks back to the good old days, whether the good old days were 50 years ago or a thousand.

As punishment for these modern evils, the Talmud goes on to say, certain spiritual rights and worldly privileges of the Jewish people were withdrawn. “From the time when the Sanhedrin ceased, song was nullified from the places of feasts”: That is, Jews could no longer sing at parties. Surely this ban was more theoretical than effective, since song continued to be a central part of Jewish life for millennia. Harder to argue with is the assertion, in Sota 48a, that “from the time when the Second Temple was destroyed the shamir ceased to exist.” The shamir, as the Gemara goes on to explain, was a supernatural creature, a tiny worm capable of splitting the hardest material. It was created—or, depending on your point of view, invented—to get around a problem in the biblical description of how Solomon’s Temple was built. According to the Bible, the stones used to build the Temple were so holy that no iron could come into contact with them. But how, then, were the stones shaped? The answer, according to legend, was that the shamir hewed or bit them into the right shape. (The Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, born Yezernitsky, renamed himself after small but irresistible creature.)

Finally, the sages say, things got so bad that pleasure itself was withdrawn from the created world; “the sweetness of the honeycomb” ceased when the First Temple was destroyed, and “the taste has been removed from fruit.” It is a striking image of a life that has lost all savor. The rabbis seem to say that there is no more reason for living; all that is left for us is to repent, pray, and remember the sacred past. “Upon whom is there for us to rely? Only upon our Father in Heaven,” says the Gemara finally. This feeling of fallenness and despair has long been one of the major themes of Jewish spirituality. Fortunately, it was never the only one.

***

To read Tablet’s complete archive of Daf Yomi Talmud study, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.