Blood of the Soul

This week’s ‘Daf Yomi’ Talmud study continues to explore the real—and hypothetical—practicalities of ritual animal sacrifice

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

This week’s Daf Yomi reading introduced us to a crucial concept in the law of sacrifice: piggul, which literally means “a vile thing” or “an abhorrent thing.” According to Leviticus 7, the meat of a sacrificed animal is strictly required to be eaten either on the day of the sacrifice or the following day. If it is eaten on the third day, “it shall be piggul and the soul that eateth of it shall bear his iniquity.” The rabbis explain that eating piggul carries the harshest punishment in Jewish law: karet, the divinely inflicted “separation” of the soul from God after death.

In Zevachim 27b, the Mishna broadens this prohibition to include offerings performed or consumed in the wrong place, as well as at the wrong time. The Bible repeatedly instructs that the Temple in Jerusalem is the only place where sacrifices are to be offered to God; the Book of Kings suggests that it took a lot of effort for the kings of Israel to succeed in centralizing worship in this way. Accordingly, the Mishna says, every component of the sacrificial process must be carried out inside the Temple: not just the slaughter of the animal, but also the sprinkling of its blood on the altar, the burning of the sacrificial portions of the animal, and the consumption of the meat.

It is not just the actual performance of these rites outside the Temple, or on the wrong day, that renders a sacrifice piggul, however. The mere intention of violating these rules makes the offering piggul; as we have seen before, in the sacrificial process, intention matters just as much as performance. Indeed, Rabbi Eliezer explains in the Gemara in Zevachim 29a that the ban on piggul must be referring to intention, for otherwise we would be faced with a logical problem. Consuming an offering on the third day renders the sacrifice unacceptable to God, according to the verse from Leviticus. But does this mean that the offering is rendered retroactively piggul for the first and second day, as well? What if a person consumed the offering correctly, on the day it was slaughtered, but then goes back and eats more of the flesh on the third day: Are we to say that the sacrifice first atoned for his sin, but then the atonement was canceled?

This implication bothers Rabbi Eliezer, who says that the time limit for a sacrifice must apply not just to when it is actually eaten, but to when it is intended to be eaten. “The verse is speaking of one who intends to partake of his offering on the third day,” he explains. But Rabbi Akiva disagrees, holding that it is indeed possible for an offering to be rendered piggul retroactively. He draws an analogy to the laws of ritual purity that govern menstruating women: A woman who experiences menstrual bleeding after having immersed in a ritual bath is rendered retroactively impure.

In Leviticus, piggul is stated with reference to time, not with reference to place. Accordingly, the Mishna rules that, while offerings are only supposed to be made in the Temple, performing the rite outside the designated area is a less serious sin than performing it outside the designated time. Place-related violations—for instance, “one who slaughters the offering with intent to sprinkle its blood outside the Temple”—disqualify the offering, but they do not carry the punishment of karet. The Gemara tries to puzzle out why time should matter less than place, engaging in some complex hermeneutical operations on the relevant Torah verses.

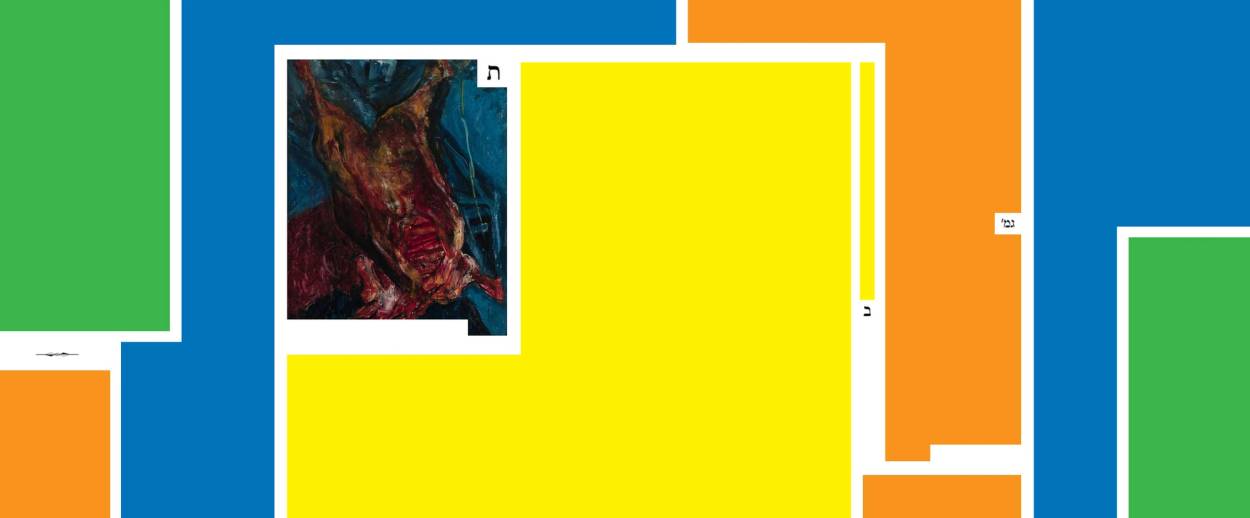

Another key element of the sacrifice is mentioned in Zevachim 25a: The blood from the sacrificed animal must be collected in a vessel, and not allowed to spill on the floor. “If the blood spilled on the floor, and the priest then collected it, it is disqualified,” the Mishna says. This means that a sacrifice involved a combination of brute strength—the knife had to sever the animal’s windpipe—and dexterity—the bowl had to be placed right beneath the wound, so that none of the blood was lost.

Indeed, the timing had to be perfect, since the rabbis explain that the blood used in the sacrifice had to be “blood of the soul”—that is, the blood that spurts out while the animal is dying. “Blood of the skin,” which seeps out when the cut is first made, is not acceptable, nor is “blood of exudate,” which seeps out after the animal is dead. Shmuel adds that blood cannot drip from the knife into the bowl; to avoid this, “one who slaughters the offering must hold the knife up after slaughter,” away from the collecting bowl. To avoid any blood being lost, Rav Chisda says that the slaughterer should “place the veins of the offering into the vessel.” This would not seem to be possible in the literal sense, since the veins are buried in the flesh; but Rashi explains that it means the bowl should be held right underneath the wound.

In the course of this discussion, the rabbis run through various hypothetical scenarios for slaughter, one more unlikely than the last. What would happen if a priest cut a bull’s ear after sacrificing it, thus rendering it blemished? Does the posthumous blemish contaminate the sacrifice retroactively? Yes, Rabbi Zeira says: The bull must be intact not only when it is killed, but also when its blood is collected. The Gemara goes on to probe whether these two stages of the process, killing and collecting blood, are in fact separable in time. Could there be a scenario, the rabbis ask, where the killing takes place when the bull is 1 year old, as required by law, but by the time the blood is collected the bull has become 2 years old, and is therefore disqualified? Rava says yes, because “hours disqualify sacrificial animals” if an animal was born at noon, then it could be sacrificed at 11:59, when it is acceptable, and have its blood collected at 12:01, when it is too old.

Of course, no one actually keeps track of the exact minute an animal is born; in the ancient world, before clocks and watches, this would have been quite impossible. But impossibility does not deter the rabbis when it comes to constructing hypotheticals. Thus in Zevachim 26a, Shmuel and his father conduct a debate over whether it would be permissible to slaughter an animal while it is suspended in the air. Shmuel says yes, while his father says no, because an animal in mid-air could not be “by the side of the altar” as required by the Torah. But how about if the animal is on the ground and the slaughterer is suspended in mid-air? Here the positions are reversed: Shmuel says it is not permitted, but his father would allow it.

This debate reminded me of the notorious discussion, back in Tractate Sukkot, of whether one could use an elephant as a wall of a sukkah. (Answer: yes, as long as it is dead and won’t walk away.) No one would ever think of actually doing such a thing, just as no one would try to rig up a harness to float a priest in mid-air while he performed a sacrifice. But actualities are beside the point here. The rabbis are engaged in thought experiments, which like scientific experiments try to abstract from real-world conditions in order to demonstrate fundamental principles. In the same way, no real-life object ever falls at precisely 32 feet per second squared, the way the laws of gravity require, because the law does not take air resistance into account. Thinking about Talmudic hypotheticals this way, I find, makes them less frustrating than they might initially appear.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.