Finding Meaning in the Margins

My prayer books connect me to previous generations, and pose questions about my own religious practice

For many years, I considered myself a “High Holiday Jew.” I had little interest in prayers or praying. But over the past few years, unexpectedly, I’ve acquired a small but emotionally resonant collection of prayer books.

When my parents died and it came time to dismantle their apartment, how could I not treasure their 4-by-6-inch leather-bound siddur, with its embedded metal plaque picturing two men praying in front of the Western Wall? My father used it every Friday night to say Kiddush. The title page announces that it was printed in “Eretz-Israel (Palestine), 1930” and was most likely acquired in 1935, when my parents went around the world on their honeymoon—”the world” constituted by Europe, Russia, and the land of Israel.

Nor could I resist the Prayer Book for the New Year that belonged to my grandfather and namesake, Nathan Silin, printed in 1913 by the Hebrew Publishing Company on Eldridge Street in New York City with facing English translation by the Rev. Dr. A. Th. Philips. The presence of the translation raised the question of Nathan’s religious practice. I had always assumed he was Orthodox. But a bit of sleuthing revealed that the small town in western Pennsylvania to which he moved with his young family in the first decade of the 20th century, after emigrating from Vilnius, had only one shul, and its decided affiliation with the Reform movement reflected a predominance of secularly oriented German Jews.

In the end, I also couldn’t resist salvaging the solemn dark blue- and gold-embossed holiday siddurim that I acquired at my 1957 bar mitzvah from The Society for the Advancement of Judaism, a Reconstructionist synagogue that my traditional father, acceding to my mother’s more progressive tendencies, had reluctantly agreed to join three years earlier. These books evoke warm memories of synagogue with my extended family, but not of praying. Consistent with the Reconstructionist ethic of adapting Jewish traditions to contemporary life and eschewing belief in a supernatural god, questions of spiritual life were given short shrift in those years. It was all about being modern, in a 1950s sort of way.

I am not a hoarder by nature, and was happy to send many of my parents’ books to Jewish archives, including my grandfather’s 12-volume Jewish Encyclopedia, which I’d coveted as a child, often taking a heavy tome or two off the shelf and perusing the unintelligible pages while leaving traces of the crumbling leather binding all over the living room rug. But the prayer books were different. I couldn’t let them go. They’re the repository for generations of family hopes and complaints, aspirations and disappointments. They offer a spiritual connection to the past that I want to sustain now that I am becoming a more regular Shabbat practitioner myself.

Acquiring the siddurim didn’t prompt my return to the synagogue. That happened a decade later, when a serious health scare led me to confront questions of human mortality with a new urgency. Claiming the books when I did, carefully sequestering them on a high shelf along with my own and my father’s frayed and fading tallisim, suggests that the seeds of a renewed engagement with Judaism were already inside of me waiting to be awakened by the ensuing life crisis. Holding the books today, knowing a little more about Jewish practices, I have new, unanswerable questions about how they were used.

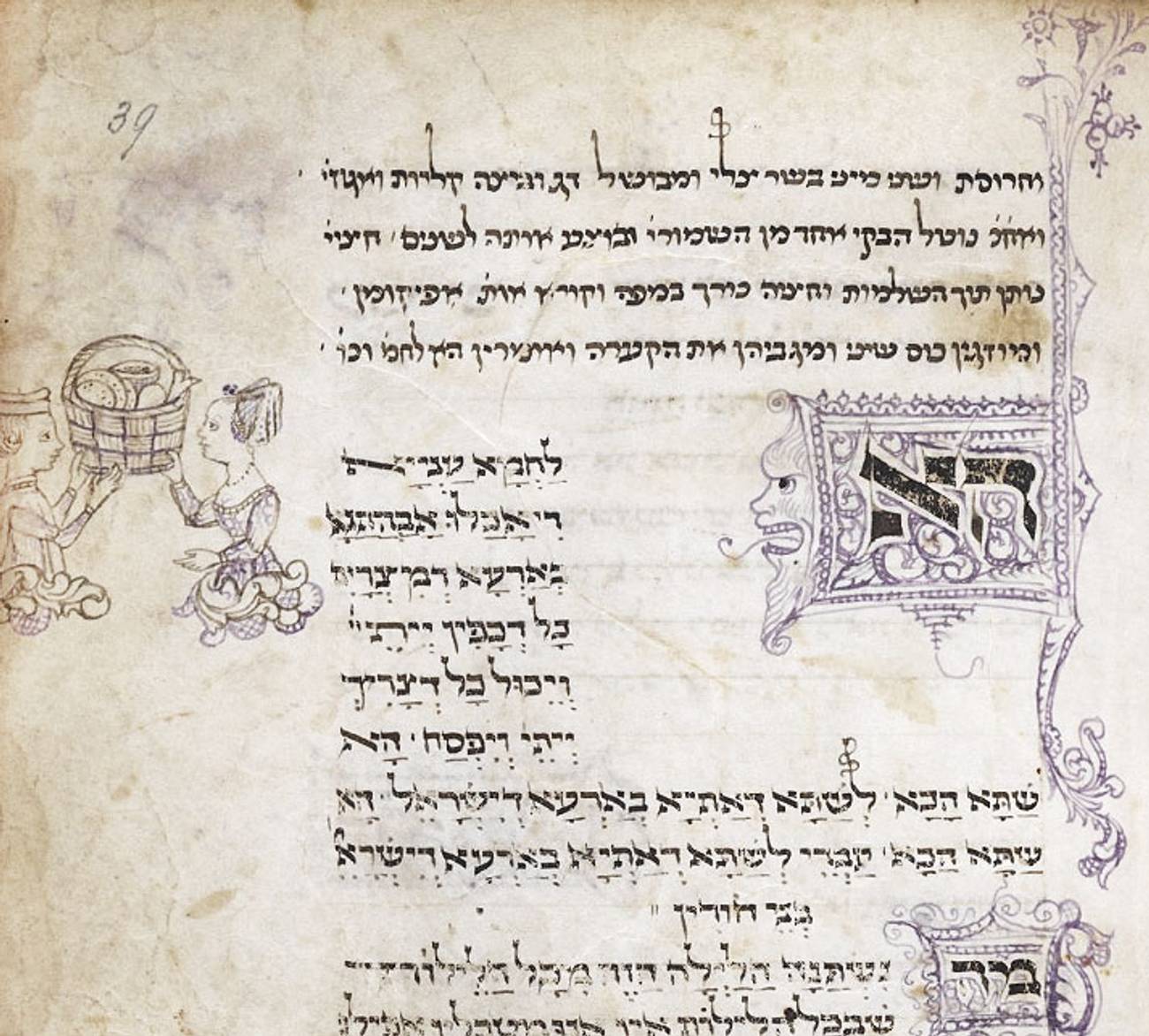

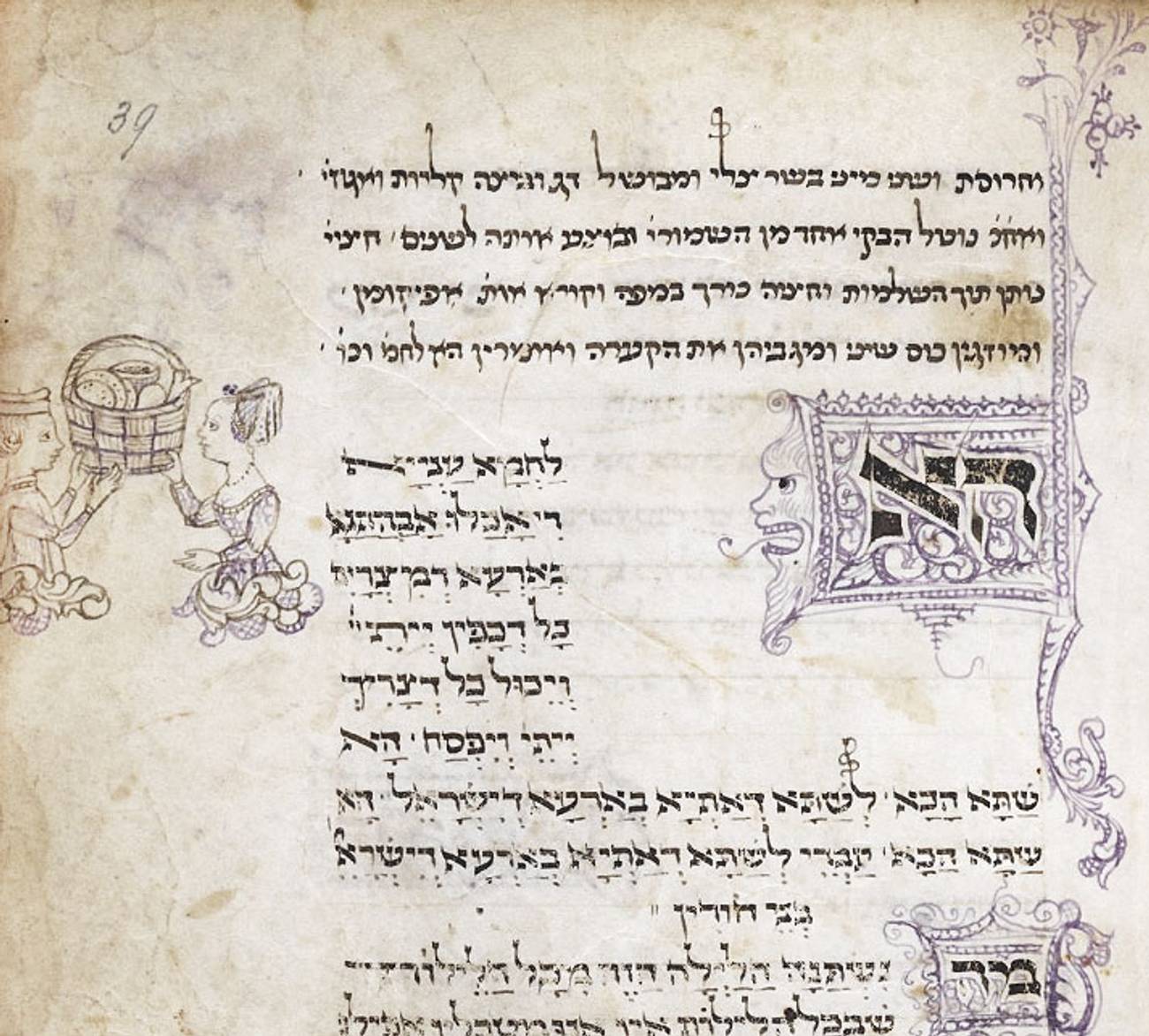

The siddurim of old cause me to reflect on the nature of the prayer book used by the small Conservative synagogue I now attend. The pages of Siddur Lev Shalem flank major prayers of the main column with margins occupied by a mixture of exegeses, poems, and complementary readings, a design that looks back to the layouts of the Talmud and forward to the modern webpage. To my eyes, the center texts announce the Judaism of my childhood. I am familiar with the literal meanings of key words and phrases, but their larger import only resonates when the rabbi offers brief commentaries about them. Left to my own devices, I feel alienated, unable to find myself or the God to whom the ancient words allude.

Over time I’ve abandoned a search for meaning in these older prayers. As the rabbi chants them, I simply let them wash over me. Momentarily losing myself—that is, my cognitive rational self—I feel sadness and elation, as all distinction among past, present, and future collapses. My expectations shifted, the prayers now provide an essential ritual container to hold the inexplicable and unsayable.

I often take up the rabbi’s invitation to peruse the siddur during services for personally relevant selections. It is in the margins that I discover the articulation that my rational self craves. Here are words that prod and provoke, to which I can affix meaning, and which in turn affix themselves to me. Some weeks I seek out familiar selections; some weeks I explore new ones. I’ve come to understand that these readings, these marginalia, function as prayer of a different kind than the texts at the center of the page. They evoke emotional and philosophical truths about the practical and existential.

In conversations with friends caring for terminally ill family I find myself referring to the distinction, explicated in the sidebar, between cure or physical repair, and the richer, more complex idea of healing that also encompasses our emotional and spiritual well being. I write the Hasidic master Simhah Bunam, also found in the sidebar, into a scholarly essay on legacy. Bunam urges us to carry two notes in our pockets at all times: “The world was created for me” and “I am but dust and ashes.” His pithy teaching perfectly captures the pendulum swings that characterize my sense of self-worth and reminds me to temper one view with the other as salutary corrective.

When describing why particular photographs are uniquely haunting, the critic Roland Barthes identifies a riveting visual element or punctum that claims our attention against the more ordinary backdrop or studium. The marginalia that I pray all have a verbal punctum. A reading from Mordecai Kaplan ends with this conundrum: “The most difficult step in achieving faith in God is thus the first one of achieving faith in oneself.” I try to hold on to this. It slips away … until next week. In a reading paired with the Mourner’s Kaddish, Chaim Stern offers this caution, “But memory can tell us only what we were in company with those we loved; it cannot help us find what each of us alone, must now become.” This hard and redemptive truth that I now read 20 years after the death of my first life partner reminds me how far I have come, and what the road has been like. I’m comforted by Stern’s words each time I come across them.

I try to approach the center and the margins of the siddur with the same epistemological humility that has stood me in good stead as an early childhood educator. What we know and the ways that we know are always filtered through our own interpretative frameworks. They are best left open to question and to a generous recognition of our personal limits. In synagogue I find myself suspended in a tension between a need for certainty, the reassurance of a knowable life, and a need to take flight, open to the new and mysterious.

The margins and center of the siddur echo the layered nature of my experience in synagogue. The marginalia engage my mind. I take comfort in their wisdom and insights. When the texts in the center are sung, their rhythms course through my body. They are a call to prayer and a container that allows me to abandon meaning. Together both kinds of texts teach me that I am more of a spiritual person than I once imagined, even if I am not following a traditional religious path.

I have made my peace with not ascribing to all of the beliefs and practices, the texts and testimonies, the synagogue proffers. To be honest, I wrestle with the talk about God, the divine, and their relationship to human kind which sounds of another time. My nonbelieving self puts up with the discomfort engendered by this aspect of Judaism because I value the space in which to believe that my individual life is a little less important than I have heretofore thought, and a lot more connected to something greater then myself. A place that is more about the soul than the ego, the spirit more than the body. And for me that place must be decidedly, if inexplicably, a Jewish one.

I have no way of knowing what my grandfather and father felt when they prayed. Their siddurim cannot convey their subjective and ultimately undefinable experiences. But these books tether me to generations gone by and at the same time elicit my gratitude for the more multilayered approach to prayer that I find in my contemporary siddur. As for the intimate relationship with God suggested by the central texts, I haven’t arrived there, at least not yet. For now it’s enough to steep myself in the intellectual provocations and existential calling-to-account I find in synagogue. Perhaps this is what it means to be a spiritual-not-religious Jew, someone who prays in the margins while allowing the chanting of the traditional texts to transport them out of time and into wordless other worlds.

Jonathan Silin is the author of four books including Early Childhood, Aging and the Life Cycle: Mapping Common Ground. He is a fellow at the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, University of Toronto, and was the life partner of the American photographer Robert Giard. He lives in Toronto and Amagansett, New York, with his partner, David Townsend.