Pray for Madness

Looking to God for answers in horrible times isn’t a rational thing to do. That may be why it’s so valuable.

Original photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Original photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Original photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Original photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

These are dangerous days for Israel and Jews everywhere. The rabbis of old, Maimonides and others, refer to times like these as eis tzara l’yaakov, a time of agony and suffering and particular peril for “Jacob”—the Jews. In these times, special prayers are mandatory.

To that end, rabbis in Israel and the diaspora have encouraged communal prayer in the form of psalms after the three-times-daily prayers, and nearly all Orthodox congregations have followed their directive. These prayers are said responsively, if also somewhat formulaically and perhaps by some tepidly. People are frightened, emotional, and deeply upset, many of them profound believers. But in the shuls that I have been in, it feels as if a fatalism takes over when we mouth the words, as if to say: Are we really going to be effective in getting God to listen to us? Since I am a believer myself, I wonder what could be missing.

When I was a little boy, I prayed in a shtibl, near my parent’s home in Kew Gardens Hills, Queens. It was a corner shul, a humble house of prayer of Holocaust survivors, most of them Hungarian. The rabbi himself was an Auschwitz survivor named Avrohom Sholom Yeshaya Wiesel. He was a cousin of the world-famous Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel.

Although a good part of the congregation had survived Auschwitz, the members were decades younger than the rabbi: They had to have been around 20 years old at war’s end, while the rabbi was 40. There is an old Tao saying that the tree breaks in the storm, but the reed bends. The younger survivors rebuilt their lives, got married, worked hard, and became prosperous, but the rabbi was both broke and broken. In a sense, he had never left Hungary. He wore the garb of another century: a shtreimel, a bekeshe, a blue silk caftan. He had a big toothy grin and spoke no English—only Hungarian, Yiddish, and an Old Testament Hebrew with which he would speak to the American youngsters.

It’s a whole new world. The old illusions are shattered. Our generation has experienced hot, hot hate for the first time.

He married after the war but had no children. His wife, a beautiful Hungarian woman who wore an elegant blond sheitl, suffered a stroke in 1980, and he descended slowly into a madness. It was not an everyday madness; it was a congenial, prayerful madness, a pious madness, maybe even a holy madness.

No matter the occasion, he would begin with felicities and niceties in an Old World Yiddish, and then within a few minutes, as though on cue, he would dissolve into hot tears, his face completely covered by his tallis, using the refrain “zeks million kedoshim” again and again, but there was a surprise: Unusual for a Hungarian Hasidic Jew with strong affinities with the Satmar Hasidic movement (known for its militant anti-Zionism), he would extol the virtues of the Jewish state, its soldiers, and its citizens, calling them kedoshim—holy ones. He not only loved Israelis, but he was a fervent Zionist who loved even the State of Israel with all its religious transgressions and its moral failings.

So much so that at the drop of a hat, in the middle of the night, he would get the “urge,” and in the pre-internet age, he would call the travel agent (for whom I worked during the summers) and ask to be booked on the next plane to Israel.

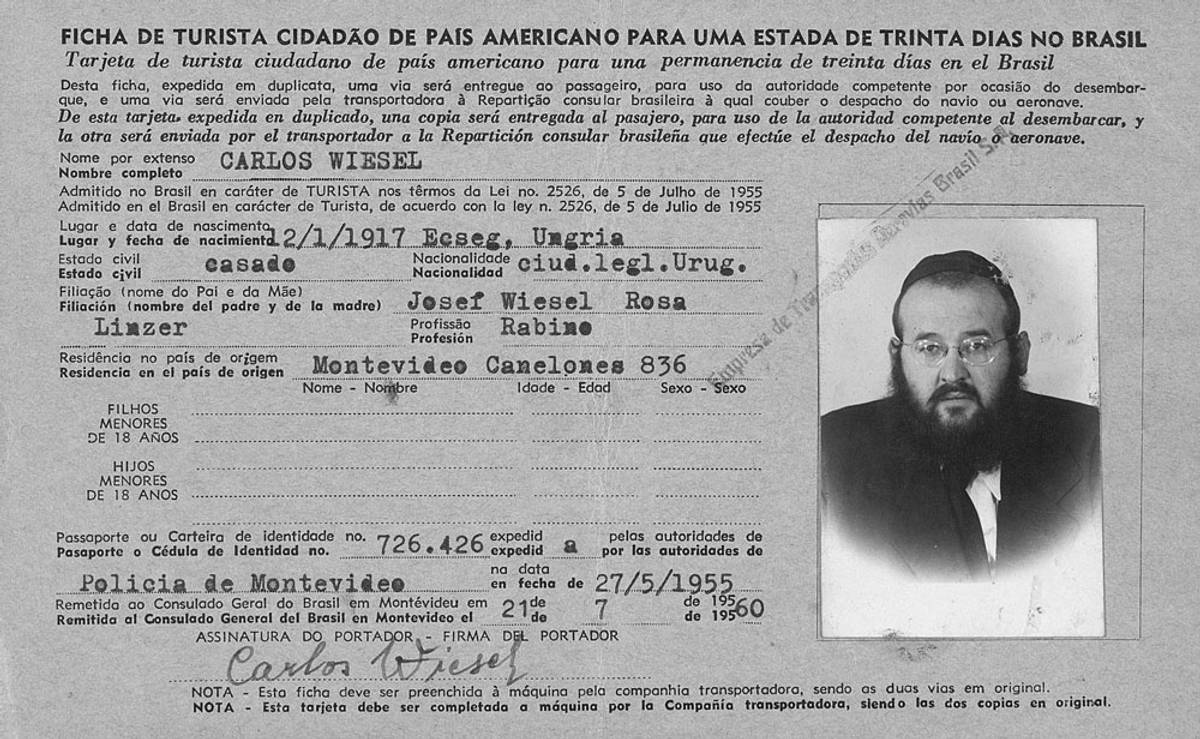

In those days, to book a ticket with a travel agent, one needed a passport number, and Rabbi Wiesel’s passport was from Uruguay. “Carlos Wiesel”—the name on his passport, and the very last moniker you would guess for a man who looked exactly like a Hasidic rebbe—had been a rabbi in Montevideo in the 1950s after the war, before he came to Queens. In the morning after the rabbi flew to Israel, people would come to shul and ask, “Where’s the rov?” Often I was the only one to know that he fled in the middle of the night on Air France or KLM or whatever carrier in those days took him to Jerusalem, where he would pray with great intensity.

He was both a curio and an embarrassment. Why did he do those things? Dissolve into tears, fly off in the middle of the night. On every occasion—bar mitzvah, bris, wedding, funeral—he would break down into heavy sobs about the 6 million and then shift to the State of Israel expressing his belief in the divine hand of God. Gilui Eliyahu HaNavi, he would announce: He had seen the revelation and appearance of Elijah the Prophet in the trenches and on the streets of Jerusalem.

Even some of the survivors ridiculed his mysticism and piety. I remember one survivor whispered to the other in shul, “Why does he daven such a long shemoneh esreh [silent devotion]? You know, I remember him in the lager [Auschwitz] and he didn’t daven such a long shemoneh esreh there.”

Although he seemed to be coming apart, he was also hard as steel. He prayed loudly. Particularly after his wife got sick, he would scream out loud, “Master of the universe, send a complete healing to the sick among your people.” But one of the congregants, also a survivor of Hitler’s Holocaust and a doctor, told us that his wife would not heal. She would not get better no matter how hard he or anyone else prayed. She was paralyzed with brain damage from a stroke.

Yet, as if in spite of these asides, the rabbi prayed with even more daring. He demanded a miracle from God for his wife, often banging on the bimah and the prayer stand with his fist. My generation sat there with our prayer books open, but we wrote him off, too. The rov would “carry on” but we wondered about baseball scores. In between services we would go downstairs to the rabbi’s basement and play a game we called “bottlecap” football. We “knew” that God would perform no miracle for the rebbetzin—so why pray? But perhaps, as young as we were, we understood neither madness nor prayer at all.

As I grew older and eventually became a psychotherapist, I came to understand that madness is not always a curse nor is it always an illness, nor is it to be written off. In fact, it may be something to be desired. My father, for example, was gripped by the madness of religion. For madness in general, I make few apologies, yet I was the beneficiary of his particular madness. I swim happily in an ocean of Talmud every day that would not have been possible save for his obsession for the word of God. In my father’s madness, he bequeathed to me an empire of learning.

For some, their madness, its intensity, and all-consuming quality is only a curse, but many in my field of psychoanalysis, like the thinker/psychoanalytic philosopher Michael Eigen, argue that madness could, in some people, open up a dimension of great significance. The task of a good therapist or even a good society is to help the individual turn his madness into something else—perhaps a journey to the self or an illumination of an idea for others—or perhaps a prayer.

The romantic in me can sometimes see madness as a privileged mode of comprehension. In a sense (but only in a sense) one can treasure madness. In the rabbi, there was a totality to his prayers and his nearly blind love of the people of Israel. It was intense and all-consuming like romantic love.

In the madness of war and trauma, there is a dissolve between self and other, a dissolution and overlap of self, king, God, and country. In madness, clarity of ideas combines with gibberish. There are dangers to rationality in love and war. Can one have a rational war, a rational love affair?

Mythic heroes often undergo wounds, disfigurement, defilement, and a horrible death as part of a larger conversion process. Rabbi Wiesel projected his own personality on to the State of Israel. He saw in Israel a projection of himself: something that had to go through a purification through torture and punishment, its frailties, its wounds, its traumas and suffering, its miracles, and ultimate strength.

It seemed odd to me then, but now for the first time I see a certain sense to it.

Sitting in synagogue since the outbreak of war against the Jewish people, many are shell-shocked. It’s a whole new world. The old illusions are shattered. Our generation has experienced hot, hot hate for the first time. We still have friends, but we can no longer condescend to our enemies and the hatred they possess. We are forced to encounter them with all their terribleness, there in Israel and here in the U.S.

I used to think that prayer was a form of madness. It is one of the most irrational things we do. Why should the rabbi pray that his wife recover? It was futile. And yet, I now see that the old rabbi’s prayers were possibly a prayer for madness: My wife won’t get better, but let me be crazy so that I can pray. Perhaps the rabbi was saying, let’s pray for madness—a madness that helps us find our way as a people, broken, but still some would say beneficiaries of God’s wild, absolutely wild grace.

Alter Yisrael Shimon Feuerman, a psychotherapist in New Jersey, is director of The New Center for Advanced Psychotherapy Studies. He is also author of the Yiddish novel Yankel and Leah.