Rethinking the Apple

How the image of Eve in Parshat Bereshit foreshadowed my own path to making peace with food

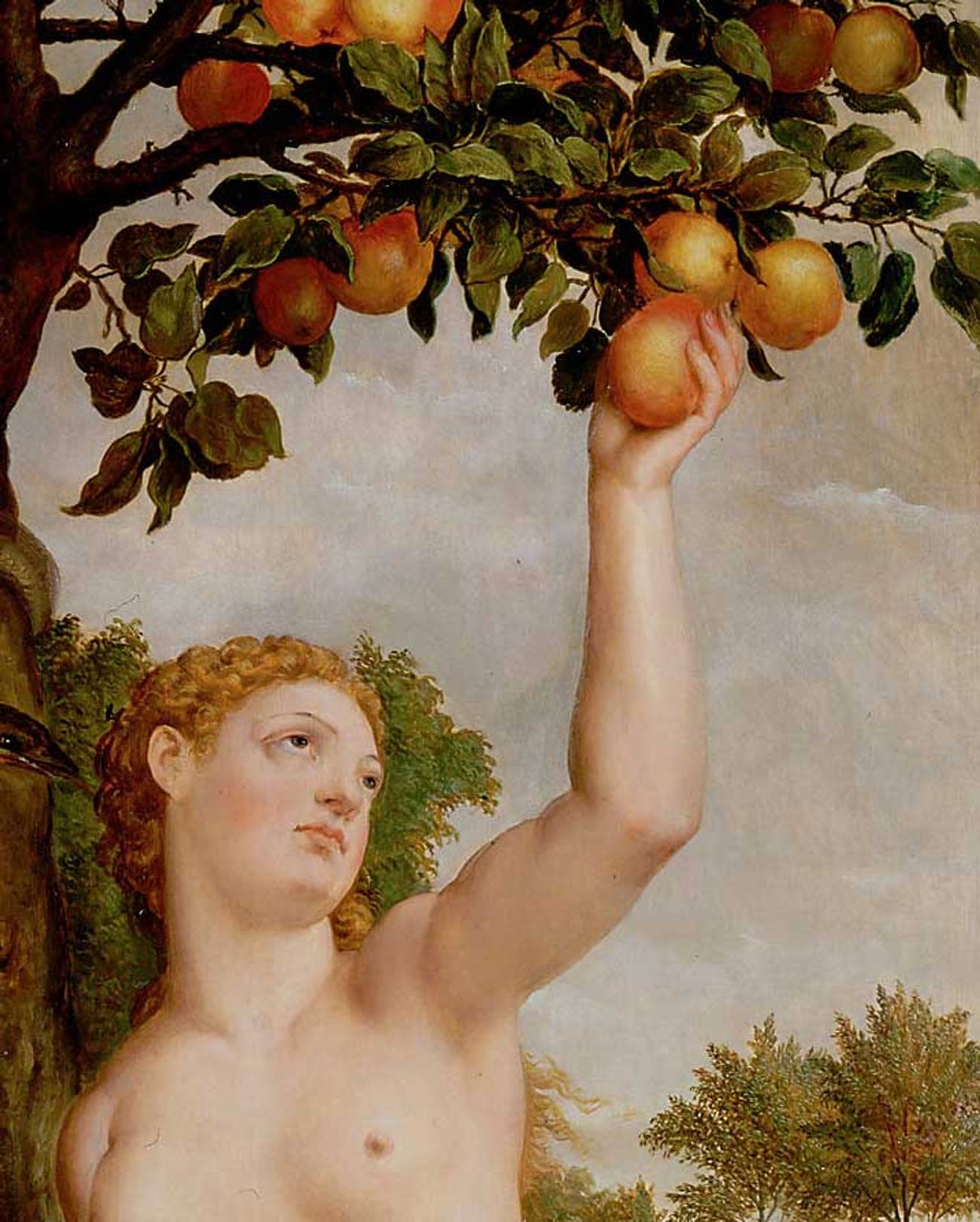

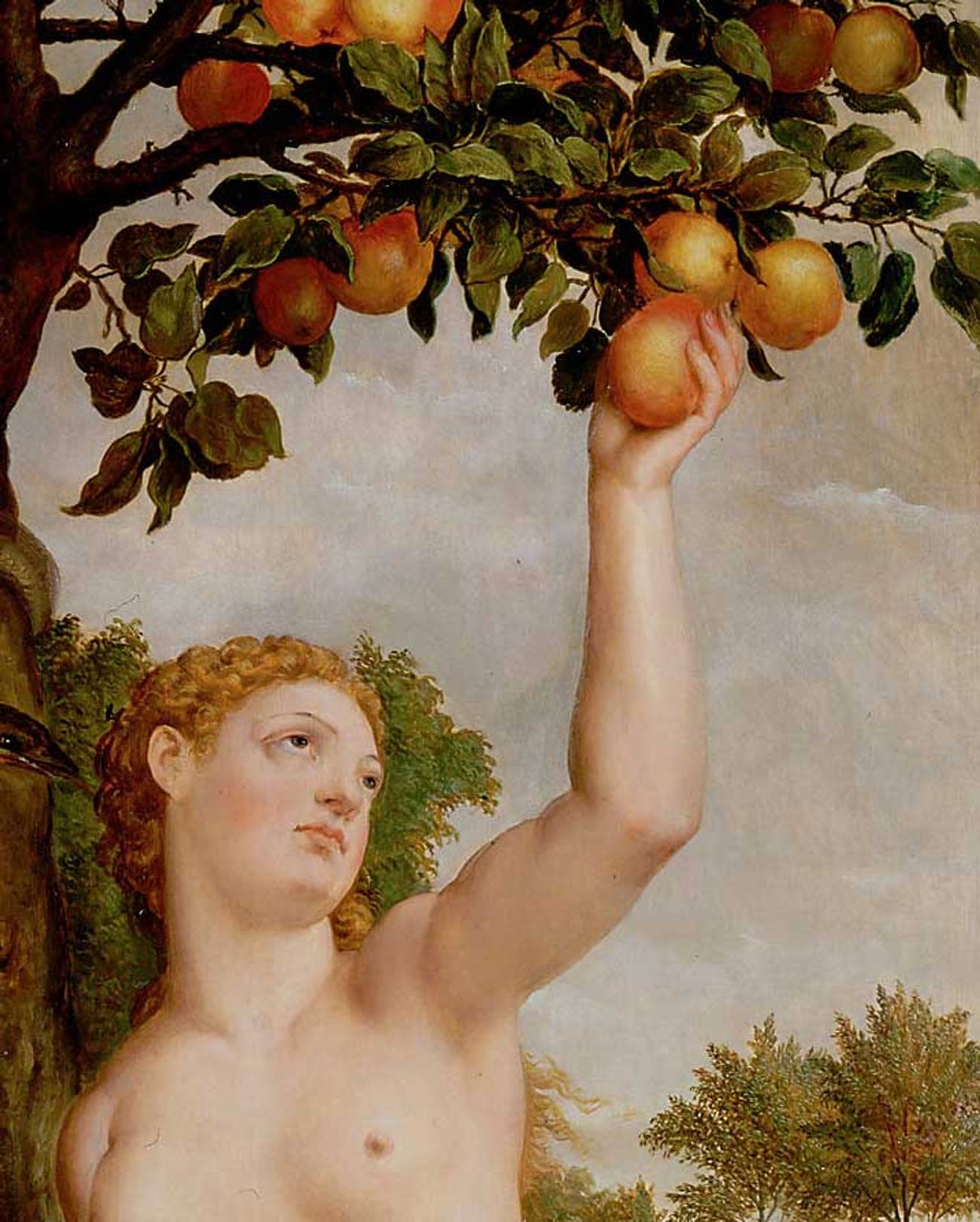

A few months ago, on a walk in the Bay Area, I found myself pausing on a street corner in front of a luxury gym. The exterior flaunted a poster twice my height, featuring a brunette staring at me from underneath her bangs with a certain look: indignant to disdainful. She was barefoot, crouching down to the earth, surrounded by wildflowers and a backdrop of soft clouds. From the side, she actually mooned the viewer, an on-brand message of contempt. She wore a flowy, tulle top in the color of her skin. Her image reminded me of Eve in the Garden of Eden, just before temptation struck—as she was designed to. It was no surprise to encounter her alone, as she’d attract both the male and female gaze. The only other piece missing was The Apple, which I imagined looming just beyond the camera’s reach.

As symbols, apples carried within them entire landscapes of association. They presented as green and red emojis I texted my friends, wishing them a sweet new year. Sometimes they offered poor substitutes for sweetness I preferred, like ice cream or a pastry. In her 2014 essay, “Grand Unified Theory of Female Pain,” Leslie Jamieson described what she calls her female, anorexic logic: “to deny the curse of Eve and the intrinsic vulnerability of desire itself—wanting an apple, or knowledge, or a man; wanting popularity, wanting anything.”

Eve’s complex journey enters the scene in this week’s Torah portion, Bereshit, which translates to “In the beginning.” Born millennia later, I defaulted to ignoring her challenges. Hadn’t we reached the post-shame era? My generation spoke up, called out, incorporated Brené Brown’s brand of vulnerability and posted sex- and body-positive quotes on Instagram. But rushing to dismiss Eve was simplistic and dishonest. Acknowledging her, or rather the steady presence of our common battles around every turn, provided me with a real, compassionate look at myself, from the beginning.

During my early childhood in the Netherlands, the apple already introduced confusion. At Rosh Hashanah dinner, we dipped a tart Granny Smith into honey. For birthday parties, we drizzled Golden Delicious with caramel and mounted them on skewers like magic wands. My mother baked them, powdered with cinnamon, or sliced them down into quarters, as my sister now does for her children. Meanwhile, in my favorite movie at the time, Walt Disney made the apple hold poison. And that was just my introduction to its Jungian shadow.

My compatriots dedicated an expression to girls like me. They warned against uitdijen, which translates to “thighing out.” The impending curves that marked a natural departure from girlhood were cause for concern, as if blood-stained underpants weren’t enough to worry about. Even doctors discussed the thigh’s potential for expansion with an ominous tone.

As a bat mitzvah girl, I struggled to reconcile the idea of “being good” with what I did and didn’t consume. Outside our kosher-style house, I rebelled (Eve’s verb) against a God and a society whose love was conditional. At home, the weight of remembering our Jewish community’s ancestors who survived on tulip bulbs took up the remaining space. Our family relied on food as safety and scarcity, affirmation and escape, love and suffering, indulgence and regret, sustenance and morality, often all at once. I longed for a place of nuance, on and off my plate.

During the decade of my adolescence, Naomi Wolf wrote that “a culture fixated on female thinness is an obsession about female obedience.” Throughout the ’90s, what drew me to apples was their appearance on a list of foods that lacked points; Weight Watchers constructed the genre that offered a loophole for a capitalist system that praised restriction and consumption simultaneously. By 2005, two years after I’d graduated from high school, Coca-Cola introduced Coke Zero. The concept of zero, meaning nothing, had maintained its philosophical appeal. Behold, the sudden possibility of a woman who feeds herself without the inevitable reprimand of guilt and shame.

In college, while attempting to foresee my real adult life, I envisioned myself in a specific category of sinners, the overweight kind. I spent a month at a weight-loss facility I jokingly referred to as fat camp. That summer evoked a complicated mix of privilege and despair, which I tempered with humor. Campers from across the U.S. were in attendance. We munched on salads and levitated to the gym, where I tried to sweat and stretch myself into self-worth.

At fat camp, we were confined by a campus with sterile dining halls and framed charts of calories (one apple = 100). Meals were repetitive and the friends I’d made referred to themselves as “The Jell-O Mafia.” Our diet-tolerant desserts turned into commodities. One weekend, I traded mine for a ride to the local bookstore.

That summer, I yearned for a return to life as Eve in her garden stage. That’s what happens to someone who is raised by the dichotomy of good and evil; I’d been socialized to crave a mythologized before. Still, I had started to notice the fallacies inherent to my task. Nostalgia, even for the most potent imagery, was only ever a doorway into an ever-distracting semblance of control. If I ate/weighed/wore/looked like X … then what? The human condition would remain so terrifyingly what it was.

For the bulk of my 20s, I sought healing and recovery in church basements of the Twelve Steps, where believers expanded “addiction” to include eating too much or too little. I found a sponsor, who recommended half an apple at a time because a whole one would spike my blood sugar. In movies, Hollywood conveyed an appealing program, glamorizing the circles of people linking hands and reciting biblical prayers. My therapist thought the same way about AA’s spinoffs, which applied the staples of fellowship and abstinence to other personal trials.

Around my early 30s, I stopped following her suggestion. For decades, I’d held onto the Disordered label, intrinsically broken by my loss of balance on the tightrope of want and willpower. Though my Abrahamic foundation had prepared me for an addiction framework that incorporated a Higher Power, I felt constricted. To rewrite the narrative, I replaced my meetings with literature and music.

I took in anew the lyrics I’d favored without knowing why while becoming a grown-up. Gradually, I came to view my relationship with food in the spirit of singer-songwriter India Arie, who sings, “I’d be starving if I ate all the lies they fed.” I immersed myself in the life-affirming writings of Rebecca Solnit, Caroline Knapp, Roxane Gay, and Glennon Doyle.

In her recent memoir, Untamed, Doyle cites the moment in her upbringing within a religious context when she was first taught to mistrust her desires. As a 10-year-old, she received the lesson of Eve as a cautionary tale about “doing what we want to do instead of what we should do.” The history reverberated into her life as a mother of daughters, when she describes asking the young women and their friends if they’d like a snack. In lieu of answering her, they regard each other. How could we know our body’s hunger when we’ve been educated to fear it?

Reading Doyle’s account of Sunday school prompted me to reflect on mine. We’d both been told of Eden in the same breath as so-called sin. And we learned the art of shaming our full-grown bodies as we were about to inhabit them. I began to recognize the ties between the Torah’s origin story and my own formative years, a personal genesis. The lifelong discomfort around food made more sense, when it evolved from an introduction to right and wrong as a moral binary.

From the gym with crouching Eve outside, I walked to a patio with socially distanced patrons and ordered an iced tea. Sipping my cold drink, I watched a group of three young women. No older than 14, I estimated, they aimed to keep up with the bodies that had overtaken them. Their preoccupation with a seemingly embodied self was striking, holding in their stomachs while combing ponytails with their fingers and assessing each other’s nails, instructed as they were by the world to morph desire and perception. One of them got up and strutted to the next table, creating a catwalk. As she spun around, hand on hip, another inserted her scalp into the third friend’s orbit, asking, “Does my hair smell nice?” I resisted my urge to share the poster of Eve, to invite them around the corner and read together from the command adorning her torso in all caps: MAKE YOURSELF A GIFT TO THE WORLD. I ached to reassure them, as I did myself: You already are.

Babette Dunkelgrün is a freelance writer and editor.