Signed, Sealed, Delivered

In Tractate Ketubot, the Talmud gives us a master class in everlasting love

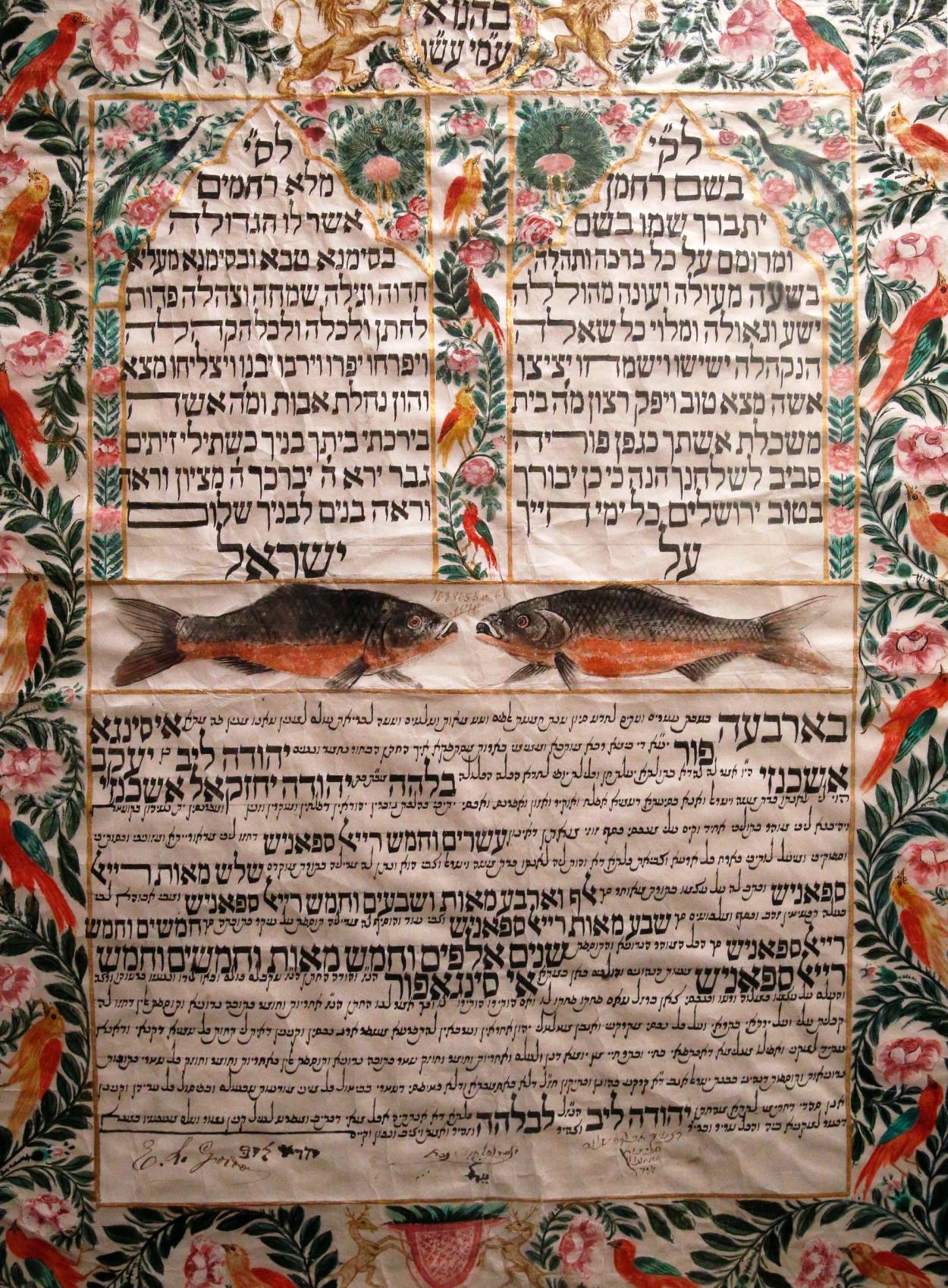

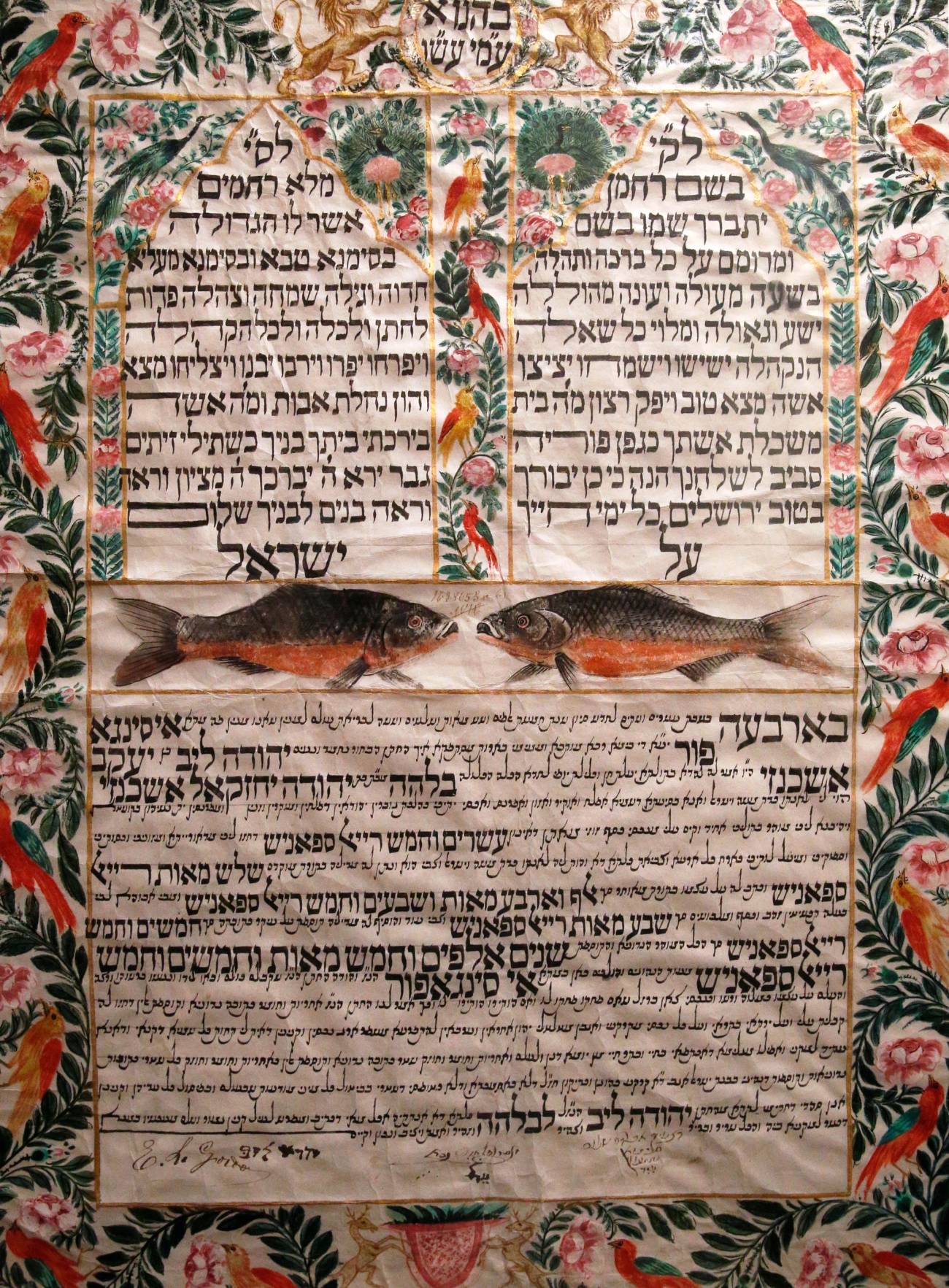

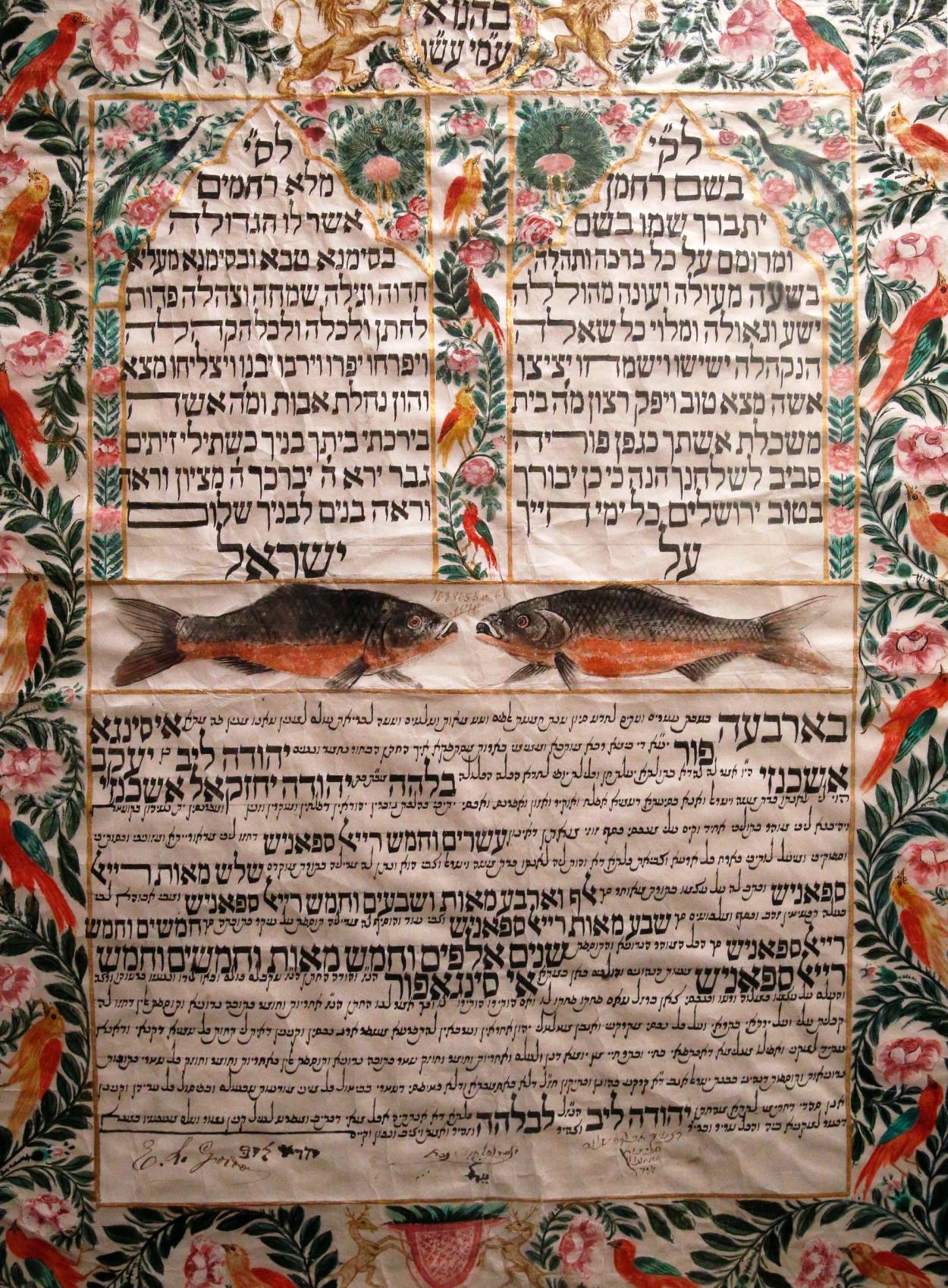

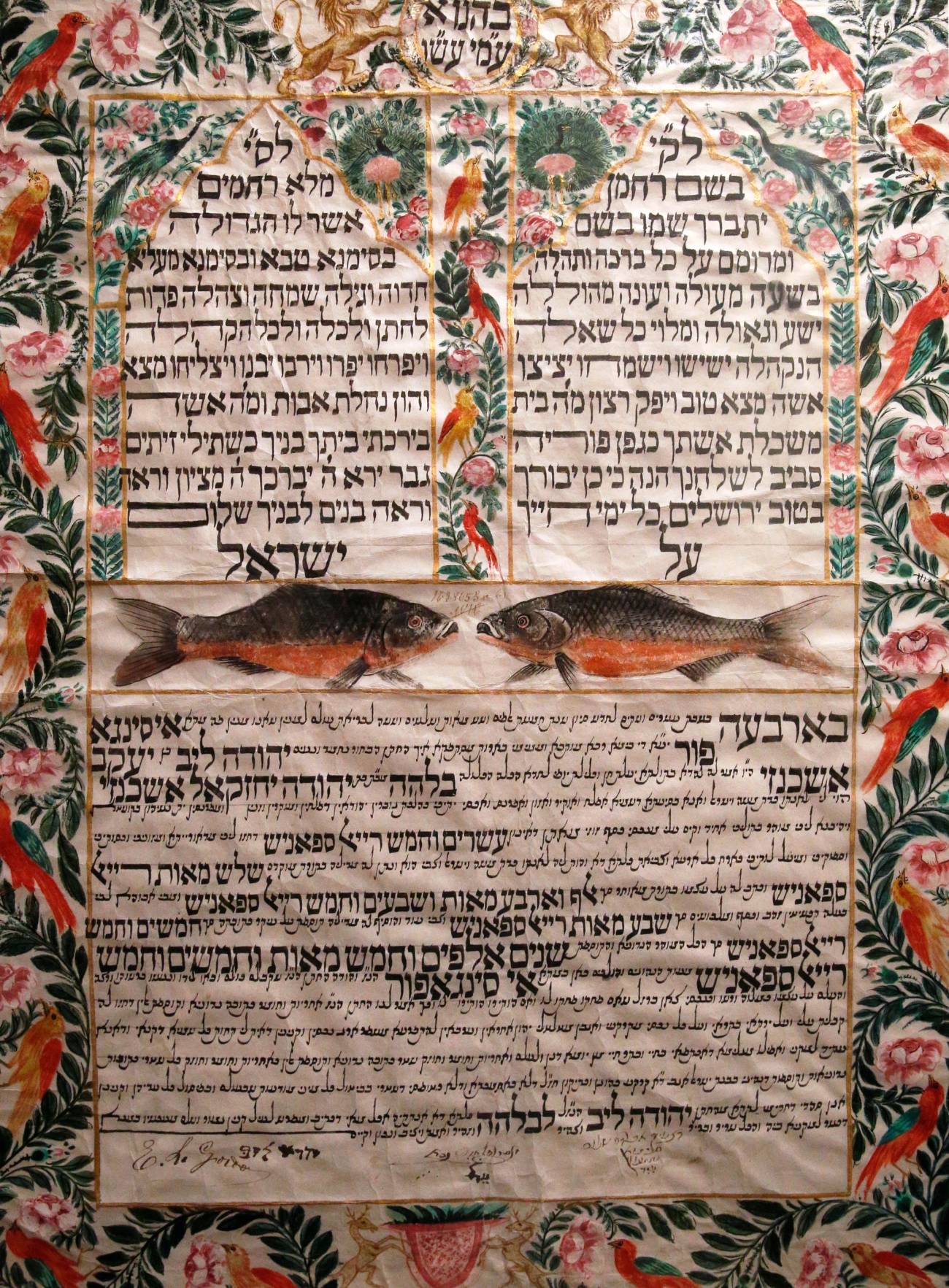

Displayed on the walls of many Jewish homes is an ancient marriage document known as a ketubah. For centuries, the ketubah has been artistically rendered, sometimes with images of biblical characters, angels playing trumpets, or flowers. Many ketubot feature the uniquely Jewish artform of micrographic script, with joyous verses serving as a frame for the marriage contract. An 1832 ketubah from the Italian city of Fiorenzuola features the text of the ketubah framed within a magnificent Baroque palace, on top of which sat a general on horseback, most likely Napoleon. According to professor Shalom Sabar, the foremost expert on decorative ketubot, the custom of decorating the ketubah may be close to 1,000 years old. And after learning Tractate Ketubot, the Talmudic tome dedicated to the laws of the ketubah, this custom feels strange: Marriage is beautiful and all, but the ketubah is a technical document detailing certain financial obligations during the marriage and ensuring a dowry in the event that the marriage dissolves. Which, let’s be honest, isn’t exactly the stuff great art is made of.

A student once asked his fairly serious rebbe whether he should hang up his ketubah in his home. “Are you accustomed to hanging up all of your financial documents?!” the rebbe responded. And in a sense, I understand this reply. Afterall, the ketubah does not contain the glowing romantic wedding vows recited at Catholic ceremonies. Instead, the ketubah delights us with such deeply romantic stuff as who precisely owns the bride’s furniture or the 200 silver pieces the husband promises to pay in the event of divorce. That’s a far cry from “to have and to hold, from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, until death do us part.” So, why did this mundane financial document guaranteeing the rights of the woman become so paradigmatic of the Jewish marriage? And why would we bother decorating it?

Because, as the Talmud explains, the ketubah may not coo sweet nothings but it goes a long way toward making a marriage work by making divorce more difficult. Without a precise monetary sum due upon the dissolution of the marriage, then any fight, any miscommunication, any bad rom-com you were forced to sit through could be grounds for divorce. A ketubah, however, ensures that since a significant sum of money is due if the marriage were to end, husbands will be more thoughtful before calling it quits. The Talmud explains: “Why was the ketubah enacted? So she will not be inconsequential in his eyes to enabling him to divorce her.”

It’s a far cry from the “happily ever after” that usually concludes fairy tales, but the Jewish concept of love is different. It’s concerned not with romance but with responsibility, the sort forged by common obligations, daily rituals, the pedestrian commitments that preserve a marriage on a dreary cold day when no one has taken out the garbage yet. It’s the responsibility that is told through shopping lists displayed on the fridge and commitments that motivate you to get out of bed to refill your spouse’s water bottle. The ketubah is deliberately banal because enduring love only emerges through actual commitments. After the ever after, the ketubah preserves that foundational love concretized during the wedding but amortized through responsibilities and duties over the course of the entire relationship.

Which is why the enduring love of Jewish marriage, as sacredly concretized within the ketubah, deliberately focuses on what happens after the marriage. Because a part of Jewish love is the love that extends beyond the loving relationship. And something about the modern world of love and dating makes this form of love even more valuable and important to foster.

Ghosting is a case in point. The term is new but the phenomenon it describes probably isn’t: Ghosting is when one party in a relationship suddenly ends all communication with the other person without any explanation. It’s probably gotten worse now that so many relationships are fostered through a torrent of texts and other digital communications. We’re able to fall deeply in love more quickly, but we’re also able to simply disappear when the going gets too tough. As one writer lamented, we place so much important emphasis on sexual consent in modern society, but no one ever asks permission to ghost. It’s no wonder, then, that some call ghosting a modern form of trauma.

In a very real sense, the ketubah is the halachic mechanism to prevent ghosting. A husband and wife are not allowed to live together without a ketubah. If the ketubah is lost, another special replacement ketubah must be redrafted. In order to have intimacy there must first be the safety of accountability. And part of the accountability of love is the commitment to care even if the love dissipates. A relationship that can be ghosted leaves those involved wondering whether the relationship even ever existed in the first place. By centering the ketubah as the affirmation of Jewish love, we are also recognizing the gravity of love’s responsibility.

And not only the love we feel to our husband or our wife: The love that is fostered between spouses within Judaism is emblematic of the love between God and the Jewish people. We should be lovesick with God, Rambam writes. Nearly all the customs of Jewish weddings parallel the revelation of God at Sinai to the Jewish people. Sinai itself was our chuppah. In 1731, the great kabbalist Rabbi Moshe Hayim Luzzato, even drafted a ketubah with the Shechina, the mystical experience of God.

He wasn’t merely being poetic. We all have seen what relationships with God look like without the enduring responsibilities of a ketubah. A relationship without a ketubah exists so long as it is convenient and fun. Without a ketubah, we may have Shabbos, but just as long as it isn’t too onerous or comes at a bad time. We may have prayer, but just as long as we have enough free time and the synagogue isn’t too far away. Without a ketubah, every relationship, even the one we have with Creator of the universe, runs the risk of fading away once things are no longer hunky-dory, convenient and comfortable and gratifying. But throw in our binding contract, and everything changes. Because the ketubah doesn’t end with a happily ever after; it ends with the much more soothing phrase ha-kol sharir v’kayum, Aramaic for everything is valid and enduring. It’s a fitting testament to lengths of Jewish love—a love beyond love, a love even when you don’t feel in love, a love that can’t just disappear but endures through commitment and responsibility. Enduring, that is, ever after.

הדרן עלך מכסת כתובות והדרך עלן

Dovid Bashevkin is the Director of Education at NCSY and author of Sin·a·gogue: Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought. He is the founder of 18Forty, a media site exploring big Jewish questions. His Twitter feed is @DBashIdeas.