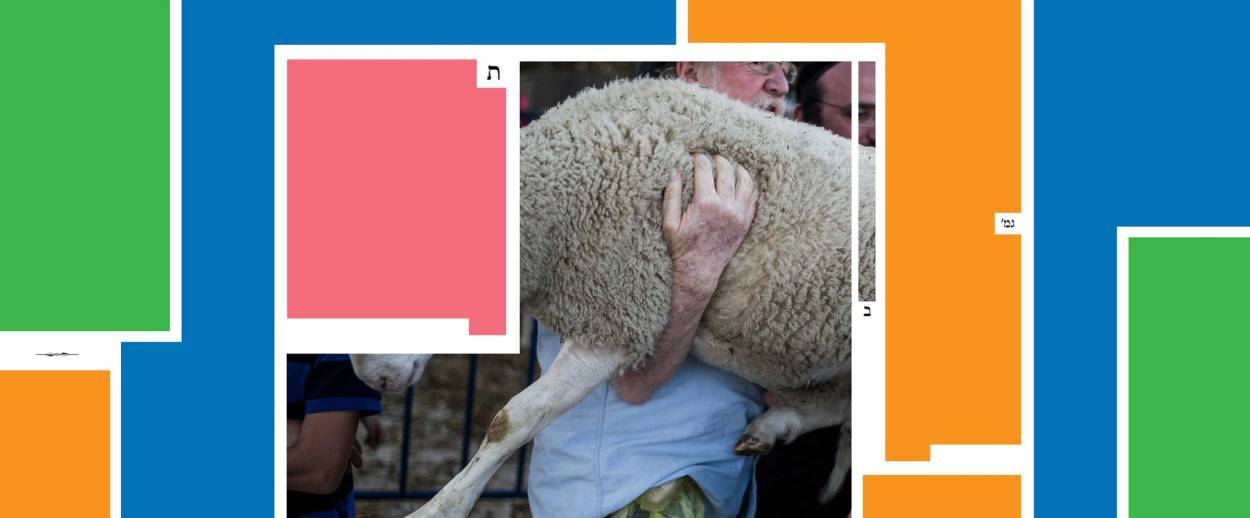

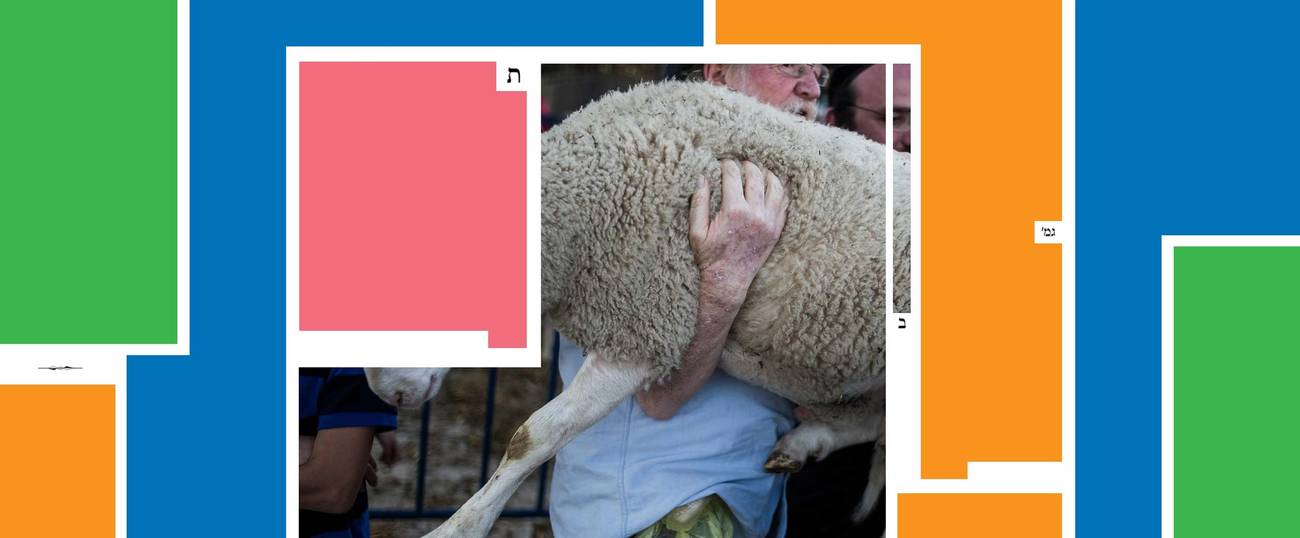

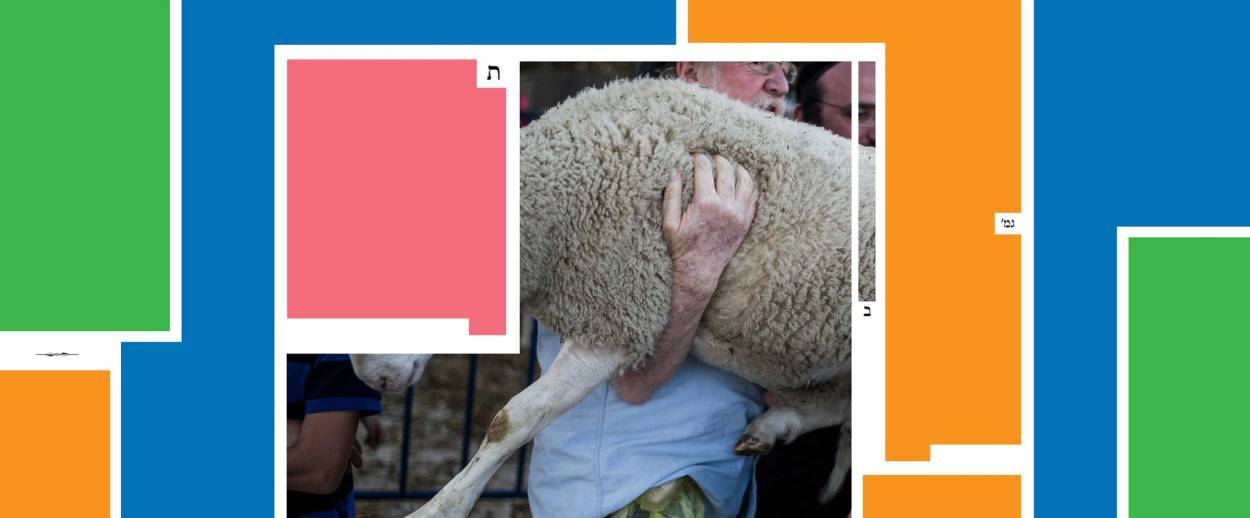

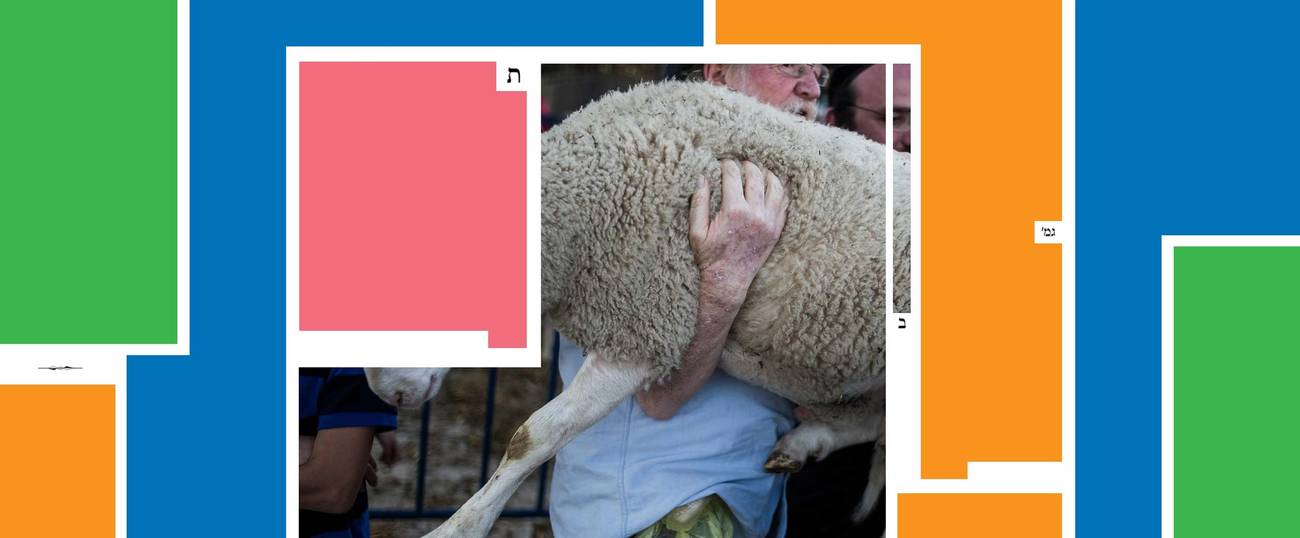

Slaughtered Offerings

In making animal sacrifices, says this week’s ‘Daf Yomi’ Talmud study, ancient Jews learned the importance of doing religious actions with deliberate purpose

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

This week marked an important milestone for Daf Yomi readers, as we came to the end of Seder Nezikin, the “order” of the Talmud dealing with civil and criminal laws. Over the last two years, we have explored many facets of this large subject, ranging from negligence to property disputes to homicide. Indeed, Nezikin includes most of the topics that you would find in a secular legal code, since its primary concern, as its name suggests, is “damages”: the many ways human beings can hurt one another and the community at large, and how they can make restitution for those injuries.

This week, with the beginning of Seder Kodashim, the focus shifts from the worldly to the divine. Kodashim—literally, “sacred things”—deals primarily with the services and rituals performed in the Temple in Jerusalem, which the rabbis call the Beit Hamikdash, the “sacred house.” For most of the remaining Daf Yomi cycle, which ends in January 2020, we will explore the complex rules governing sacrifices and offerings in the Temple.

The Temple has never been far from the Sages’ thoughts in the earlier sections of the Talmud, and we have already learned a good deal about it—for instance, how the major Jewish holidays were celebrated there, and how funds were collected for its upkeep. Likewise, the topic of sacrifices has come up innumerable times in our reading so far. In this column, I’ve usually avoided discussing those passages, since they are highly technical and often felt like digressions from the main subject. But now sacrifices will take center stage. The tractate we began this week, Zevachim, is named for the “slaughtered offerings” that were the core of the Temple service.

In an obvious sense, the Temple and its animal sacrifices are the least relevant part of the Talmud for a modern Jew, since they deal with an institution that has not been in existence for almost two thousand years. That is why many codifications of Jewish law omit these subjects entirely. Until the Temple is rebuilt—which the Sages believed could happen at any time, with the arrival of the Messiah—all the rules governing sacrifices are purely theoretical.

Yet this did not stop the Sages from analyzing these laws with their usual meticulousness, since the Temple service was one of the core elements of Judaism. “The world stands on three things,” according to a famous saying from Pirkei Avot: Torah, avodah, and deeds of loving-kindness. The word avodah is usually translated as “service” or “worship,” and today it is often construed widely to mean all kinds of service to God. (In modern Hebrew, it means work or labor, as in the name of the Labor Party.) But in its original context, avodah specifically meant the Temple service, the daily and yearly cycle of sacrifices and offerings prescribed in the Torah.

The amount of space devoted to sacrifices in the Torah suggests that they were very important to God. But why, exactly? Could the Creator of the universe really have been hungry for the aroma of burnt meat? Yehuda Halevi, in the Kuzari, ponders this question: “You slaughter a lamb and smear yourself with its blood, in skinning it, cleaning its entrails, washing, dismembering it, and sprinkling its blood. If this were not in consequence of a divine command, you would think little of these actions and believe that they estrange you from God rather than bring you near to Him.”

Finally, however, Halevi concludes that sacrifices must have had a real efficacy, guaranteed by God, even if human reason couldn’t understand why or how they functioned. Maimonides, on the other hand, developed a rational and historical analysis. In and of themselves, he argues in the Guide for the Perplexed, animal sacrifices mean nothing to God, who has no body or senses, and certainly doesn’t inhale their smoke. If Moses commanded the Israelites to offer sacrifices, it was only because, in his time and place, they were considered a normal part of religious practice. If he had tried to deprive the Israelites of sacrifice, they would have been confused and distraught—just as modern Jews would rebel if you told them that God doesn’t hear prayers (which, Maimonides implies, he doesn’t).

The Talmud, of course, does not engage in this kind of philosophical argument. Nor does it begin, as a novice might wish, by simply laying out the schedule of sacrifices in the Temple and the proper way to perform each of them. As is usually the case, the Sages assume a reader already knows this information, from the Torah or from prior learning. Rather, they start by considering a specific legal issue: What is the status of an offering that is slaughtered “not for its own sake”?

In Zevachim 2b, we read that “the offering is slaughtered for the sake of the offering”—that is, it must be offered as a particular type of sacrifice. There are several kinds of sacrifices described in the Torah, including sin offerings, guilt offerings, peace offerings, and burnt offerings, each of which has a different purpose and involves different types of animals and rituals. The implication here is that, as we have seen in many other cases in the Talmud, intention matters just as much as action. If a slaughterer kills an animal for a burnt offering but he thought he was doing it for a sin offering, or vice versa, the sacrifice is flawed, because it was “slaughtered not for its own sake.”

The Gemara draws a comparison to a bill of divorce, or get. Just as a get must be written for a specific husband and wife, so an animal must be slaughtered for a specific sacrifice. However, the mishna in Zevachim 2a draws a fine distinction: The sacrifice “did not satisfy the obligation of the owner,” but it is nevertheless considered “fit.” In other words, the wrongly intended sacrifice can be offered up to God, but the person who offers it must go back and start over with a new sacrifice that is offered in the correct spirit.

The Gemara goes on to ask just what this distinction signifies. “Reish Lakish raised a difficulty while lying on his stomach in the study hall,” we read in Zevachim 5a, in a novelistic touch. “If offerings are fit, let them propitiate God, and if they do not propitiate God, why are they brought at all?” In what sense is the sacrifice “fit” if it doesn’t do what it is supposed to do? Rabbi Elazar responds by citing a case in which the fitness and the effectiveness of an offering are separate issues: that is, when the person in whose name the sacrifice is offered has died. This could happen, for instance, if a woman who is about to go into labor designates a certain animal as a burnt offering, to be sacrificed after she delivers, but then dies in childbirth. In this case, her heirs are supposed to carry out the burnt offering. Apparently such a sacrifice is fit to offer to God, even though it cannot atone for its owner, since she is no longer alive.

The intention to bring the proper kind of sacrifice is just one of the elements required. “The offering is slaughtered for the sake of six matters,” we read in Zevachim 2b. The first, as we have seen, is “for the sake of the particular offering.” Second, it must be “for the sake of the one sacrificing”: the identity of the owner of the sacrifice matters. If the slaughterer receives an animal from Reuven, but when he kills it he believes he is doing so for Shimon, the sacrifice is flawed.

Third, it must be “for the sake of God”: the sacrifice must be carried out with the conscious intention of propitiating God. Fourth, “for the sake of the fires”: the slaughterer must intend for the animal to be burnt on the altar. Fifth, “for the sake of an aroma,” which is integral to the sixth, “for the sake of pleasing.” If any one of these elements isn’t consciously present in the mind of those carrying out the sacrifice, it is flawed, though it is still “fit” to be offered up. Here is one answer to the philosophers’ objections: Sacrifice is not only a ritual or a formula; it is supposed to be a conscious act of honoring God. As always in Judaism, what you do matters because of why you do it.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.