Slaughtering With Intent

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi,’ why a Jew may not sacrifice an animal in such a way that its blood flows into the ocean, and other rules protecting worshippers from the limits of paganism

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

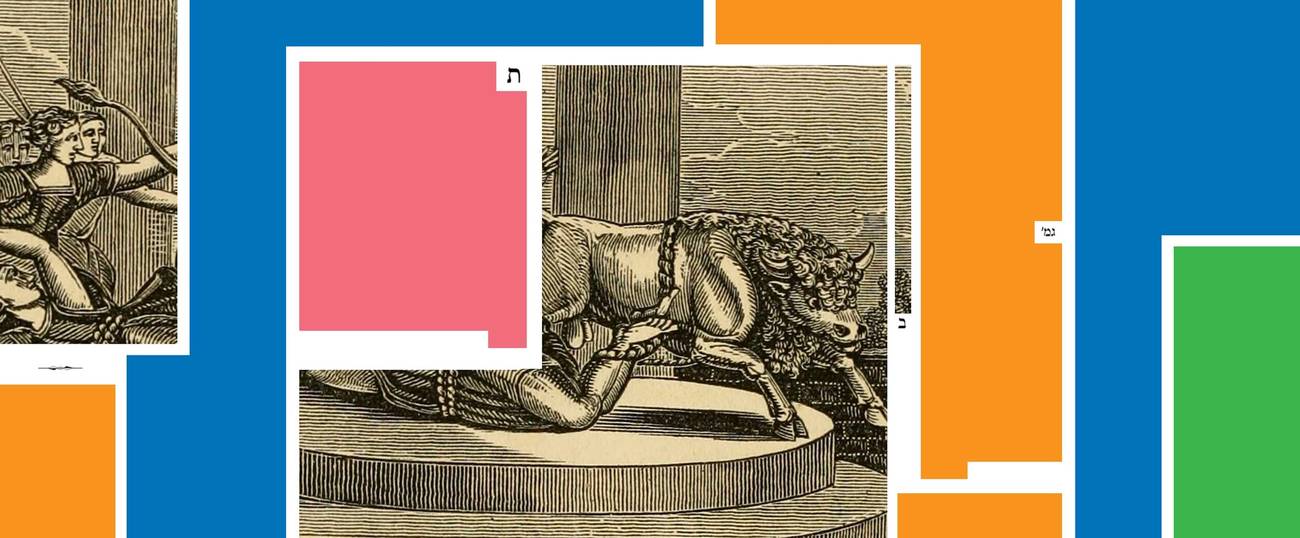

Tractate Hullin is premised on the idea that animal slaughter is a religious act. This is obviously true when the animal is sacrificed by a priest in the Temple, where it is being offered directly to God. But even slaughter outside the Temple, for human consumption, is governed by Jewish law, which is why a Jew may not eat meat from an animal that was slaughtered by a non-Jew. In Hullin 38b, however, the rabbis wonder about a somewhat different question: What if an animal belonging to a gentile is slaughtered in kosher fashion by a Jew? Can the Jew partake of the animal’s meat, or does the legal status of being owned by a gentile render it forbidden?

The problem arises because, in Talmudic times, it wasn’t only Jews who saw animal slaughter as a religious act. Most people in the Roman Empire in the first centuries CE were pagans who regularly sacrificed animals to their gods. As the mishna says in Hullin 38b, “the unspecified intent of a gentile is for idol worship”: Unless he specifically says otherwise, one can assume that a pagan who slaughters an animal is doing so with a religious purpose.

The question, then, is whether the pagan intention of the animal’s owner cancels out the Jewish intention of the slaughterer. Rabbi Eliezer says it does: Even if the pagan intends to eat only the smallest part of the animal, the slaughter is considered idol worship, and a Jew may not derive beneift from any object of idol worship. (The exact animal part Eliezer refers to is unclear: The Hebrew term is translated as “the diaphragm” in the Koren Talmud, but it literally means “the lobe of the liver.”) For the same reason, as we saw earlier in Tractate Avodah Zarah, Jews may not buy or sell wine from pagans, much less drink it, since this wine was commonly used in their religious rituals.

But the majority disagrees with Eliezer, and the law is that a Jew may eat an animal belonging to a gentile, so long as it is slaughtered by a Jew in kosher fashion. That’s because, Rabbi Yosei explains, what matters is the intent of the slaughterer, not the intent of the owner. He derives this principle by analogy with Temple sacrifices. There, in the Temple, it is the intention of the priest performing the sacrifice that matters, not the intention of the person who owns the animal being sacrificed. Indeed, according to Rabbi Yosei, even if a pagan explicitly told the Jewish slaughterer that he intended to use the animal for idol worship, a Jew could still partake of its meat, so long as the slaughter itself was performed properly.

Indeed, the Gemara says in Hullin 39b, such a case once arose in the town of Tzikuneya, when three Arabs came and “gave rams to the Jewish slaughterers. The Arabs said to them: The blood and the fat are for us, for use in our idol worship, and the hide and the flesh are for you.” (Naturally, this took place before the birth of Islam, which postdates the Talmud.) The slaughterers consulted Rav Yosef, who replied that it was permitted to make this deal, since it was the intent of the slaughterer that mattered.

The Gemara also raises a parallel question. The mishna assumes that the owner of the animal is an idol worshiper, while the Jewish slaughterer is not. But what if a Jew slaughters an animal with the intention of using it for idol worship—to “sprinkle its blood” or “burn its fat” on the altar of Mercury or Venus? Of course, if he actually performs these rituals, he is guilty of one of the worst crimes in Jewish law and deserves both the death penalty and karet, eternal separation from God. But what if he strictly follows Jewish law in performing the slaughter itself? Could a pious Jew partake of the animal’s meat, knowing that it was slaughtered with idolatrous intentions?

Rabbi Yochanan says no, relying on the legal principle that a Jew is forbidden to derive benefit from anything associated with idol worship. But Reish Lakish, surprisingly, says yes. Not only do we separate the intention of an animal’s owner from that of its slaughterer, he argues, we also separate the intention of the slaughterer during the slaughter from his intention afterward. As the Gemara says, “one does not transfer intent from rite to rite”: If a Jew intends to perform a legitimate kosher slaughter, then his slaughter is valid, even if subsequently he intends to use the blood for a pagan ritual.

Yet as Rav Sheshet objects, if one follows Reish Lakish’s reasoning, “how can you find a case of slaughter for idol worship where the animal is forbidden?” And indeed, the next mishna goes on to clarify that slaughter is not valid when it is performed by a Jew “for the sake of” something that is not God: for example, mountains, hills, seas, rivers, or other natural features that were associated with or believed to embody a pagan deity. Indeed, if two people were cooperating in the slaughter, and only one of them had a pagan intention, the slaughter is entirely invalidated.

The next mishna goes on to broaden this prohibition, saying that even the appearance of slaughtering an animal for idol worship is forbidden. That is why a Jew may not slaughter an animal in such a way that its blood flows into the ocean or into a river: These were forms of pagan sacrifice, and a Jew must not even look like he is performing them. For the same reason, a Jew cannot collect the blood of the slaughtered animal in a vessel or in a hole in the ground.

However, the Gemara makes some pragmatic exceptions. If you are on board a ship, it’s permitted to slaughter an animal while holding its neck overboard in such a way that the blood flows down the side of the ship into the ocean. This is simply a matter of hygiene, to avoid getting blood all over the decks, and will not be mistaken for a sacrifice to Poseidon. Similarly, it’s forbidden to collect the blood in a hole if an animal is slaughtered “in the marketplace,” where other people can see it; but if you’re slaughtering at home in your courtyard, where no one’s watching, it is permitted to collect the blood this way in order to keep a clean yard. The key thing, as often in the Talmud, is that a Jew not mislead other Jews into thinking that something forbidden is permitted.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.