The True Meaning of Superman

A new congressman just swore in on a Man of Steel comic book. There’s a very Jewish lesson there.

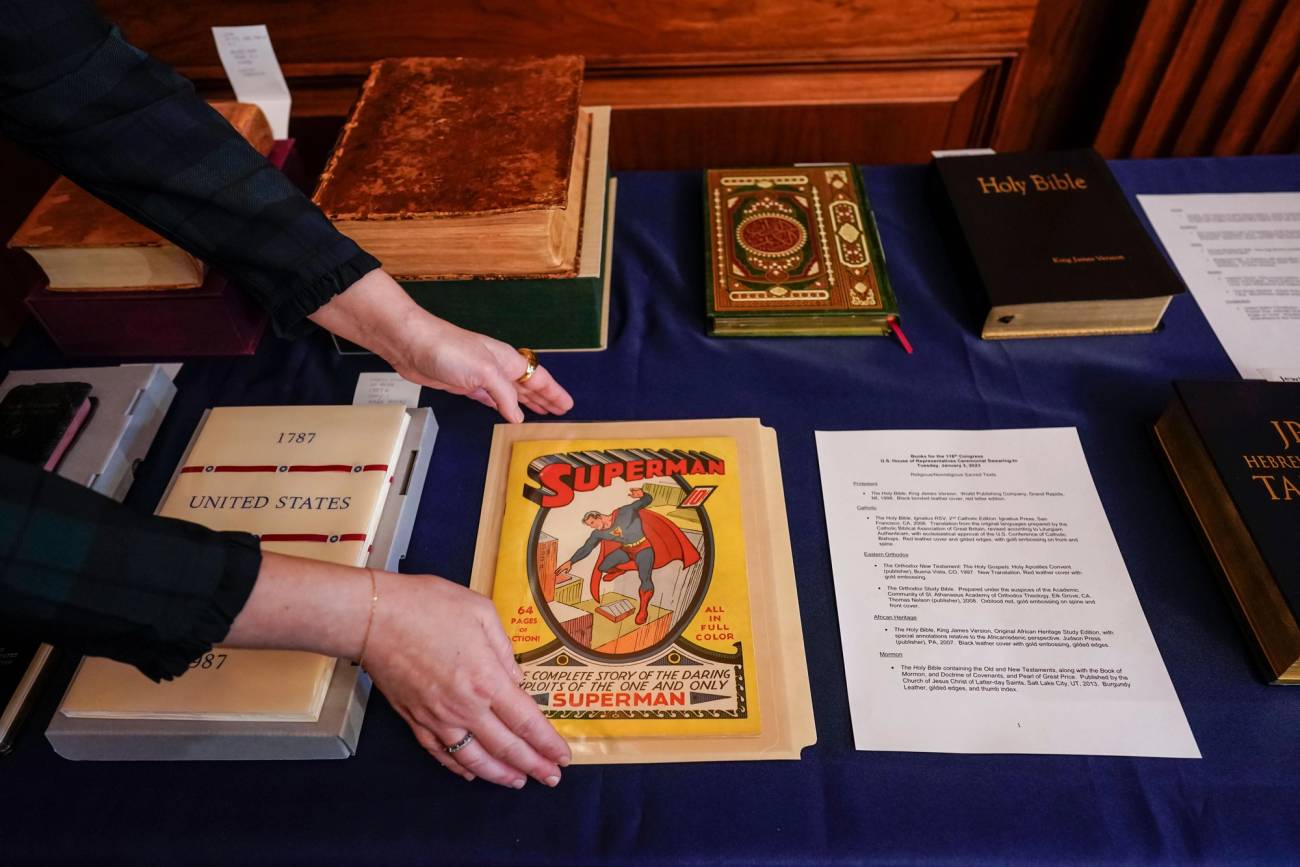

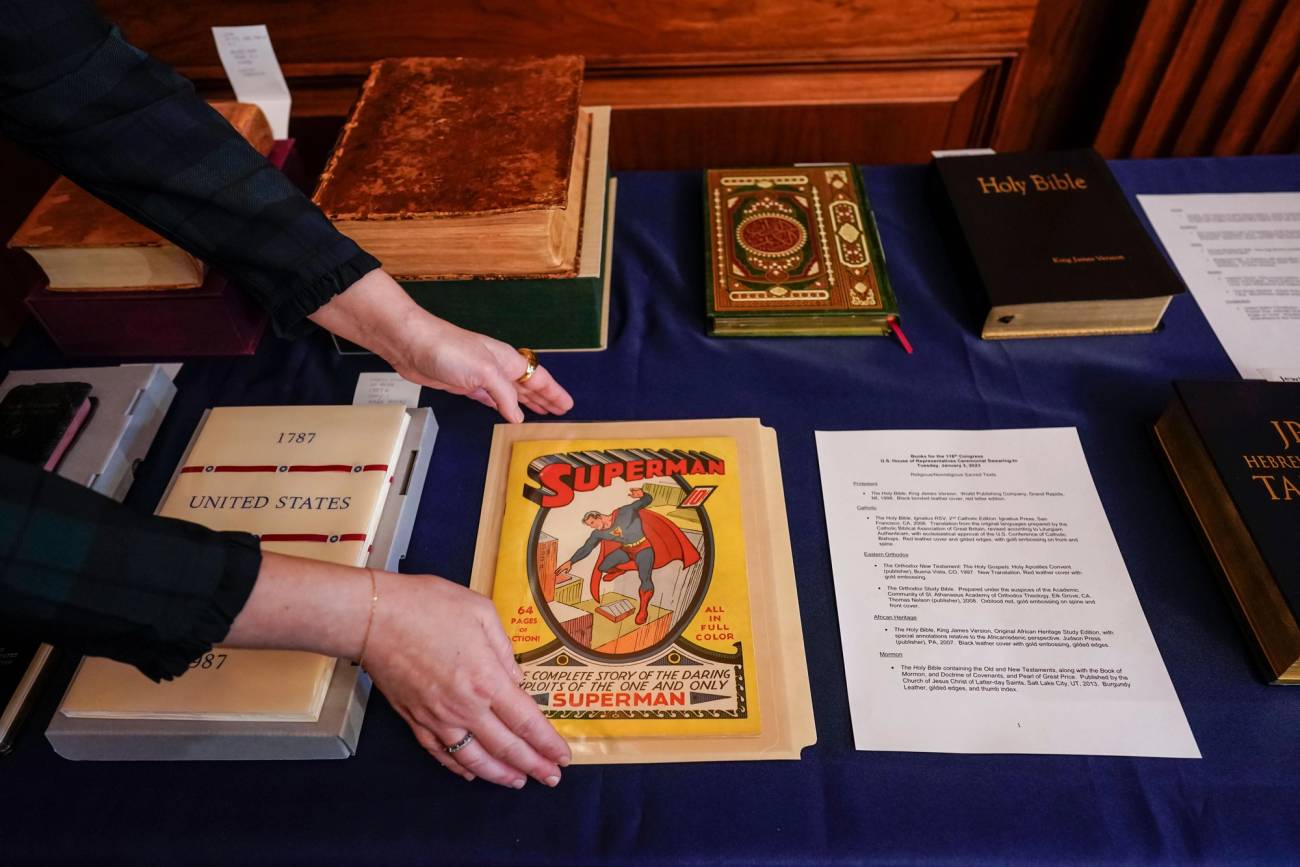

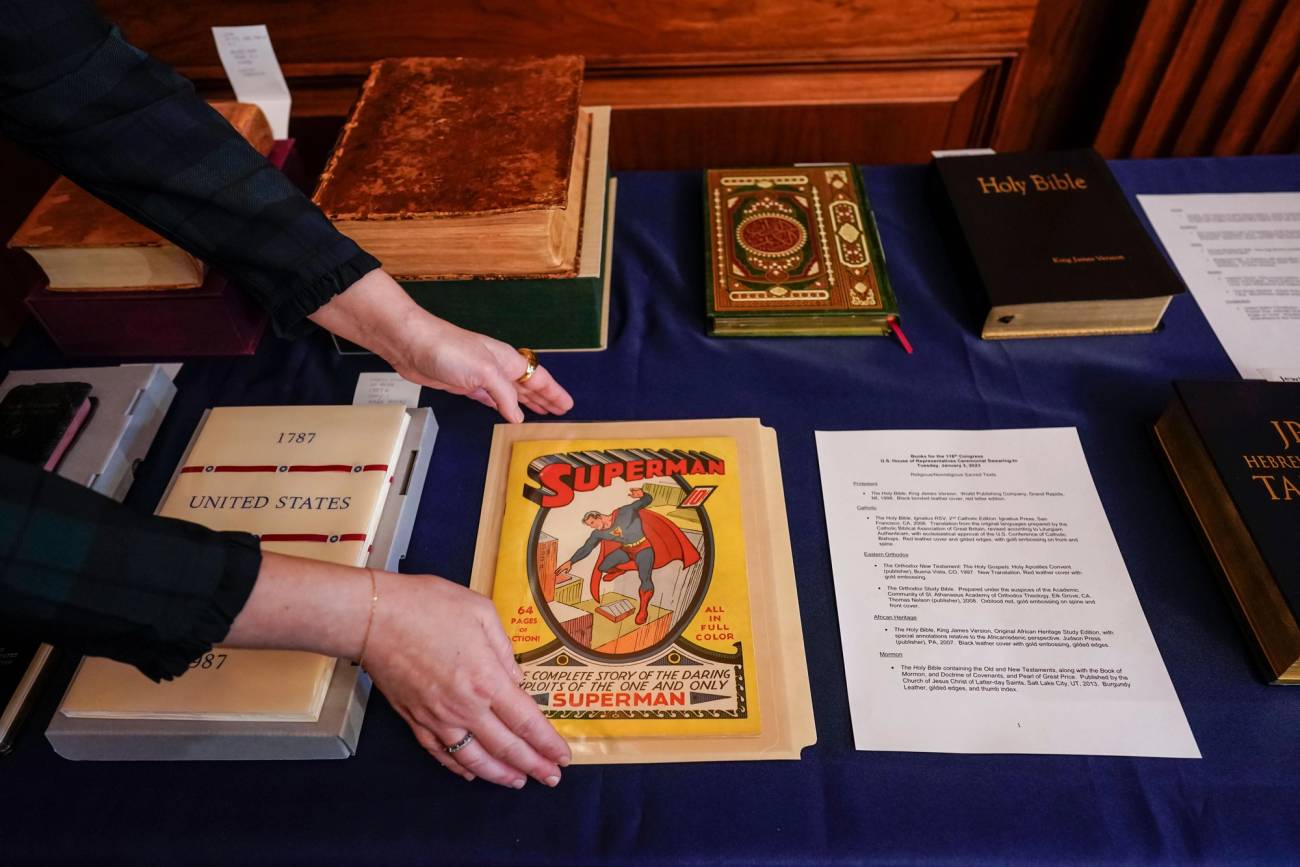

The recent drama surrounding the selection of the speaker of the House of Representatives occupied so much media attention—almost an entire week of the news cycle—that it was unlikely many would notice another unusual event connected to the installation of the new Congress. It was one with far less national significance, but in a sense, even more unprecedented: A photograph showing the various books waiting to be used for the swearing in of new members of Congress included a rare comic book, Superman, No. 1, from 1939, awaiting California Democrat Robert Garcia’s hand as he took the oath of office with the Man of Steel underneath.

As a rabbi, the thought of replacing the usual Bible with a comic book seems sacrilegious in the extreme, and I do feel the need to strongly lament that particular symbolism. And yet, also as a rabbi, there’s something about Rep. Garcia’s act that intrigues me. To understand why, consider the story of Superman.

The being born as Kal-El on the planet Krypton is, as we all know by now, “faster than a speeding bullet, more powerful than a locomotive, able to leap tall buildings in a single bound.” He can soar deep into space, or start fires with a glance, or see through walls, or crush stones into diamonds, or, on occasion, even turn back time. His abilities are seemingly without limit, and have caused countless youths to wish that, like him, they could fly above the Earth.

But Congressman Garcia didn’t focus on these superior abilities. To his credit, he said he’d chosen Superman as part of his swearing-in text because of the Man of Steel’s values: “justice ... honesty ... doing the right thing, standing up for people that need support.” To further underscore these values, Garcia bundled the comic book with both a copy of the Constitution (his main text) and a picture of his late parents and his own certificate of U.S. citizenship.

Still, the actual legacy of Superman goes even deeper than those hallowed ideals, and, in fact, necessarily precedes them and explains them. Because, read carefully, the Superman story—the one that has kept the legend enduring for more than 80 years—is all about the incredible impact of chinuch.

Chinuch is a Hebrew word we in the yeshiva world use to mean education. It is broader than mere classroom instruction, connoting also preparation and dedication. It evokes a truly awesome power, not to fly or to lift unfathomable weights but to mold the soul of another through the focused love of a committed parent or the impassioned care of a devoted teacher. It is both the ability and the responsibility to impart, through teaching and modeling, a system of beliefs and morals so effectively that another person will adopt it as their own, do their utmost to honor it with their lives, and seek to pass it on to others.

The story of Superman is the story of a being with such incredible power, he could choose to conquer the Earth, to enslave all its people, to seize all its riches for himself. And yet, amazingly, the fact is that he does the opposite, at great self-sacrifice.

We have two people to thank for his ongoing dedication and commitment to doing the right thing: Jonathan and Martha Kent (although their first names have varied throughout the decades, their characters have stayed the same). Like Moses, whose origin story is read in this week’s parsha by Jews around the world, the infant Kryptonian was placed in an ark and sent afloat for his own protection, only to be discovered and adopted. Unlike Moses, he was brought up not by a maniacal pharoah but by simple people who believed in service and in living a life dedicated to “truth, justice, and the American way.” Infused with gratitude, respect, and responsibility, the most powerful being on Earth becomes not a despot but a hero.

The inspiration that Superman receives is carried through him to others, in fantasy and in reality as well, and therein lies its enduring value. The 2012 book Superman Versus the Ku Klux Klan is actually a true story of the influence of fiction on real world awareness and activism, and the recent death of artist Neal Adams reminds us of his collaboration with Holocaust scholar Rafael Medoff on the volume We Spoke Out, detailing the efforts of comic book creators to educate on the horrors of the Holocaust through the tools of their iconic characters. Perhaps these seem like relics of a time when superheroes were heroes, rather than antiheroes or complex literary studies; perhaps such a time can still be now.

The Superman story was never about power. It was always about the impact of a strong, foundational value system, how that is painstakingly and unwaveringly conveyed by those with human vision rather than super vision, and how that effect is felt in every step, in every decision, in every mission, taken by those do who have the power.

That chinuch, that amalgamation of education and preparation and dedication, is the task of parents and of teachers, and more broadly of society as a whole, actualizing and transmitting the vision of idealistic founders. It is the work of God Himself, and would most properly be symbolized by placing one’s hand on a Bible; but God has many messengers in many forms to transmit His values and to harness human powers toward them. In a better world, the world that chinuch can inspire and create, that would be the most enduring message of a new term of American leadership.

Daniel Z. Feldman teaches Talmud and Business Ethics at Yeshiva University, is the rabbi of Ohr Saadya of Teaneck, New Jersey, and is the author of six volumes in Hebrew and three in English, most recently False Facts and True Rumors: Lashon Hara in Contemporary Culture.