A Stranger Among Us—A Catholic Boy at a Jewish Camp

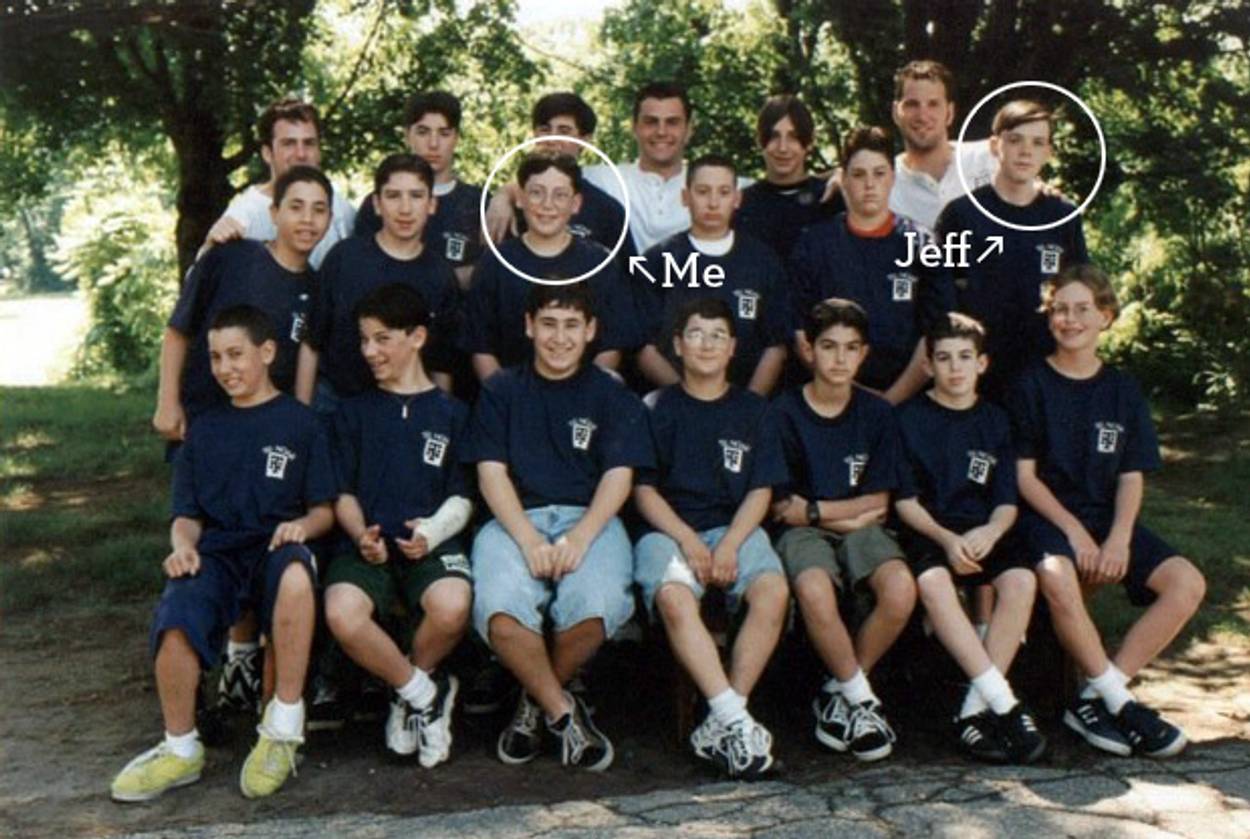

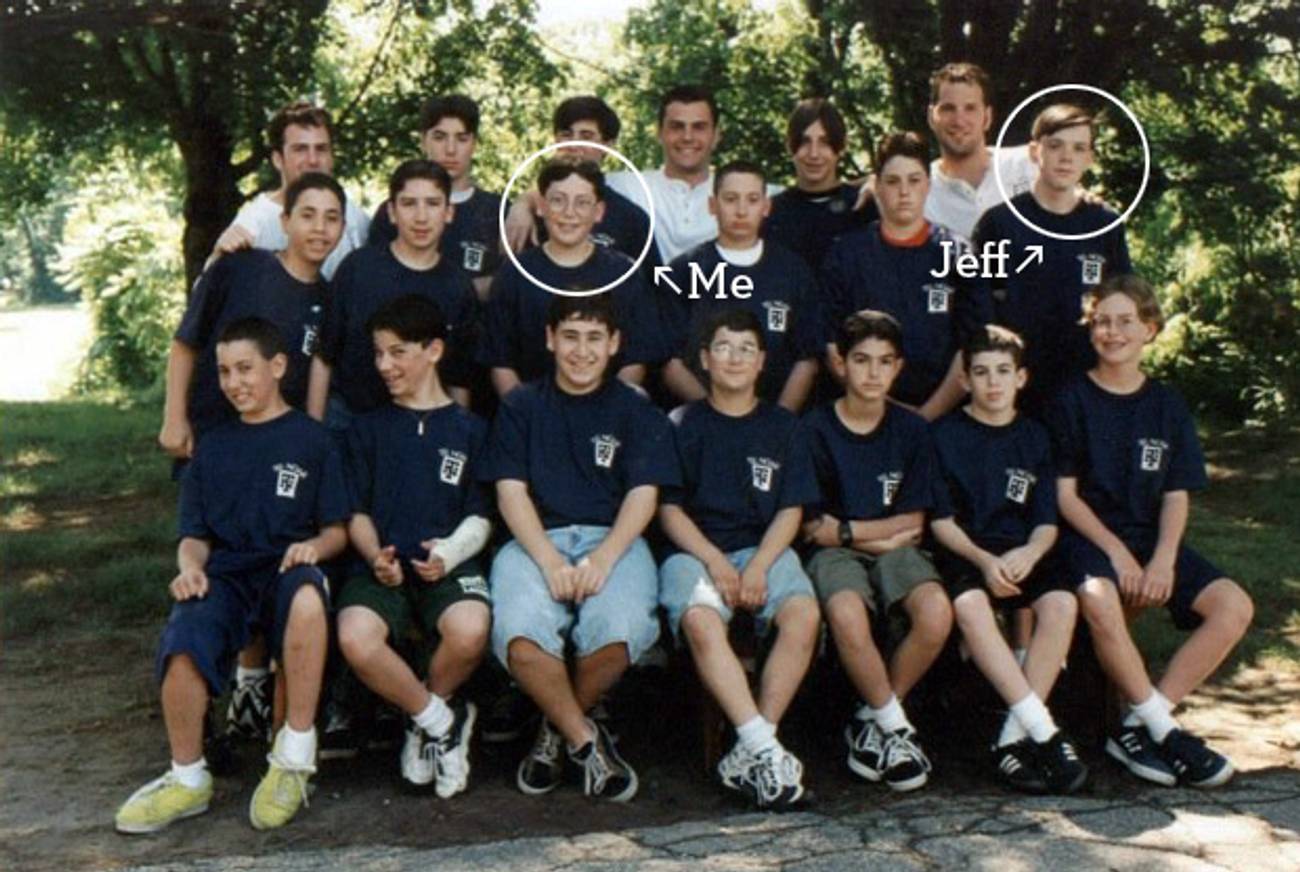

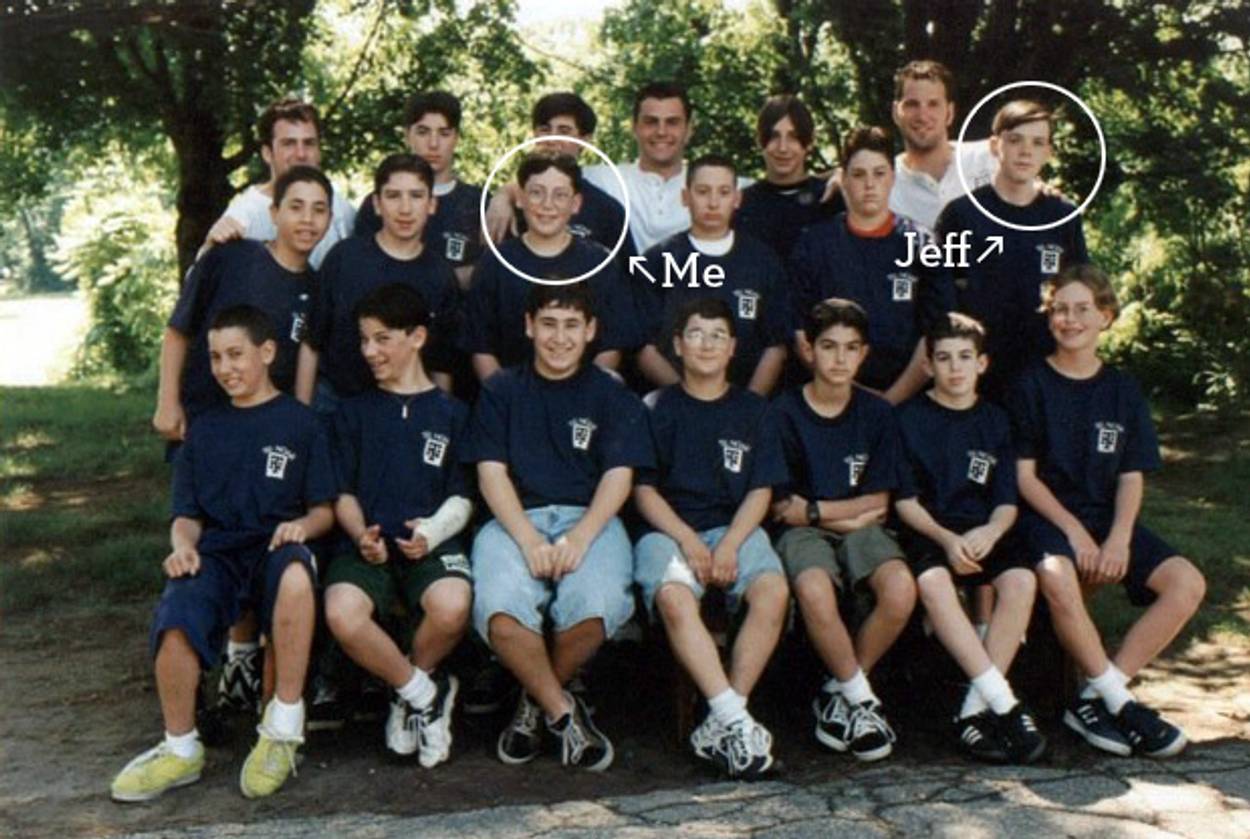

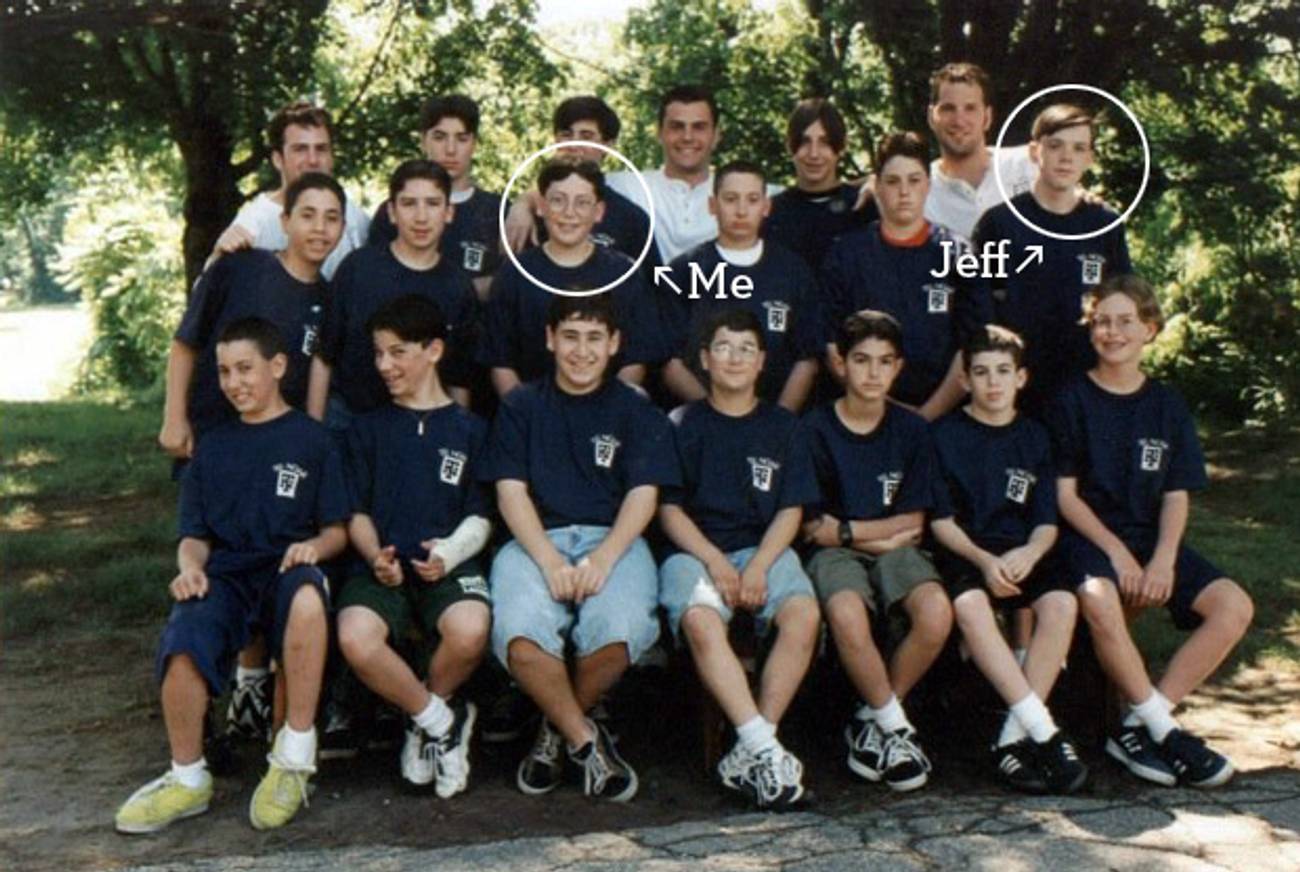

I took my Catholic friend to my Jewish summer camp when we were teenagers. Now he’s an honorary Jew.

To some kids, overnight camp is about as appealing as military school. No air conditioning, no sleeping late, no television; what kind of summer is that? But Jews are different. We love camp. Throughout the ’90s, I gave up hot showers and Sega Genesis every summer so I could spend eight weeks among New England’s Goldbergs, Schwartzes, and Cohens.

By seventh grade, my friend Jeff, who’d heard me rave about camp for three years, decided he wanted to partake in this tradition, too. The only problem was that he was Catholic. Camp Tel Noar in Hampstead, N.H., wasn’t just a camp that Jews happened to attend. It had a Hebrew name. (The direct translation is “Youth Hill.”) We ate kosher food, said prayers before and after meals, and endured Jewish culture classes. The most Jewish thing Jeff had ever done was sit through my bar mitzvah.

When I told him about camp life, I tried to de-emphasize the things I thought made it sound like a cult. I didn’t mention the endless sing-alongs, the Israeli dancing, and the Shabbat observance. At one point, he asked if he’d be required to go to Friday night and Saturday morning services. “No,” I said, lying through my teeth. It was a cowardly thing to do, but at 13 I didn’t have the courage to tell him the truth. I guess I was afraid of scaring him off. But by the end of seventh grade, his mind was made up. Jeff’s mother, if I remember correctly, took my endorsement as gospel and agreed to sign him up. So, he was coming to camp. This was both exciting and unsettling. The last thing I wanted was his ruined summer on my conscience. Plus, I was absolutely terrified that he’d think that Jews were strange.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that at Camp Tel Noar, our roles would be reversed. In American society, Jews are usually the ones doing the assimilating. I can’t say I faced much anti-Semitism growing up in Lynnfield, Mass., a town that was mostly Irish and Italian, but there were certainly times when I felt like an alien. At camp, Jeff would be the extraterrestrial, and I’d be the one helping him find a place in my world.

***

One morning in late June 1996, Jeff, whose mom used to save me leftover Easter ham, became the newest member of my bunk. Lunch that first day was harrowing—for me. As we said hamotzi, I looked over at Jeff. He wasn’t groaning. Birkat hamazon, the post-meal prayer that was often a complete slog in the stuffy mess hall, didn’t faze him either.

On the first night, after we’d unpacked and gotten ready for bed, I heard him laughing along with my friends Todd and Steve, two of the bunk’s biggest wise-asses. Over what, I have no idea. But I knew right then that acceptance wasn’t going to be an issue. For a bunch of middle-schoolers, we were a fairly welcoming group. (That summer we rallied around another new, older bunkmate who was, I think, developmentally delayed. He found his calling selling cans of Sprite to the junk-food deprived.)

Unlike me and most of our bunkmates, Jeff had not spent the previous six months attending dozens of bar mitzvahs—that school year I must’ve downed 300 Shirley Temples and 1,000 pigs in a blanket—but he quickly became one of us. And it seemed others at Camp Tell Everyone, where information spread faster than athlete’s foot, liked him, too. He made people laugh. That first summer, Jeff carried around a Chia Pet on a leash. I’ll give him credit; it was a good bit. But even as he became part of the group, he also remained the token goy. It was like A Stranger Among Us, but actually fun to watch.

And here’s what I learned: For a young non-Jew, overnight camp may actually be the best place to learn about Judaism. It’s essentially its own little society with its own set of rules, some of which are inescapable. Like the rest of us, Jeff had to celebrate Shabbat. When it was 90 degrees and the mosquitoes were biting, the weekly outdoor services could be brutal. Even though services rarely stretched longer than an hour, we found time to goof off: I once ate bugs for entertainment. Unbeknownst to me, Jeff managed to pry himself away from my sideshow and actually pay attention. “I remember being impressed that at such a young age, he was able to blend in,” Mark, an old counselor of ours, recently told me, “and to appear to be interested and inquisitive about services in a religion foreign from his own.”

It didn’t take Jeff long to figure out which rules were circumventable. For instance, the way the adults euphemistically put it, there was no “fraternization” at coed Camp Tel Noar. But as we all know, puppy love is irrepressible. I vividly remember Jeff leading the hooting and hollering after witnessing our friend Dan making out with a girl for the first time.

Food was another ambiguous issue. Snacks were allowed—I still contend that camp is the only pot-free environment where Sour Cream & Onion Pringles actually taste good—but non-kosher stuff was taboo. Still, there were counselors who knew how to get things: chicken patties from the general store up the street, leftover Chinese food, and Wendy’s Junior Bacon Cheeseburgers, which were coveted like whiskey during Prohibition. (When I worked at camp during college, a guy almost got fired for selling JBCs to campers at a significant markup.)

As it turns out, spending a summer at Jewish camp sometimes involved distancing ourselves from Jewishness. Occasionally, though, we were rudely reminded of our collective identity. Once a “townie” drove by camp and screamed, “Kikes!” Hampstead wasn’t usually that hostile, but I did get the feeling that the locals viewed the camp as an oddity. After all, every summer the town’s Jewish population increased by about 99 percent. For the most part, however, we remained undisturbed in our self-governed bubble.

Jeff never seemed bothered by camp customs, as foreign as they were. I’m pretty sure that within a week, he knew all the words to the birkat. He even willingly sang Hebrew songs with us on Friday nights. One Saturday afternoon, during some kind of biblical trivia contest, our counselors thought it would be funny to send Jeff up to the stage. I forget what the question was, but he came very close to answering it correctly. My bunk cheered for him anyway. Not all of our pursuits were so noble, of course. Once we reached Bogrim, the camp’s oldest age group, we started partaking in the “Bogrim Tradition.” This meant spending havdalah—the short ceremony that marks the end of the Sabbath—farting as loudly and as often as possible.

***

Jeff liked camp enough to come back the next summer. And the next. After three summers as a camper at Tel Noar, Jeff entered the counselor-in-training program, which included a trip to Israel. My parents, fearing for my safety, didn’t allow me to go. And so my Catholic friend went to the Promised Land without me. It was a brave choice on his part, but not all that surprising. Unlike most of the kids I grew up with, he didn’t mind escaping his comfort zone. In hindsight, though, he doesn’t quite see it that way. “Jews were normal to me at that point,” he recently told me, citing the fact that by then, he’d spent plenty of time with my family. Sometimes, he said, “I just feel like I get credit for taking some flying leap.”

Once our camp years were behind us, Jeff and I ended up rooming together at George Washington University, where we probably interacted with more Jews on a daily basis than we had at camp. Religion still comes up in conversation; recently, discussion has centered on the differences between Catholic guilt—which is usually turned inward—and Jewish guilt—which is usually turned outward. And to this day, he can still sing along with the birkat.

The things Jeff learned at a Jewish summer camp have stayed with him into his adult years. He is, in my mom’s eyes at least, an honorary Jew, even if he is about to marry a smart, beautiful shiksa from Iowa. The wedding is over Labor Day weekend. At the ceremony, I plan on slipping a glass under his foot.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Alan Siegel is a writer in Washington, D.C. His Twitter feed is @alansiegeldc.

Alan Siegel is a writer in Washington, D.C. His Twitter feed is @alansiegeldc.