Art and Words for Frances

A new exhibit spotlights the work of picture-book icons Russell and Lillian Hoban

Bread and Jam for Frances was one of my favorite books as a child. I loved stubborn Frances, the badger who sang an anthem against eggs: “I do not like the way you slide,/I do not like your soft inside,/I do not like you lots of ways,/And I could do for many days/Without eggs.” She drew a food-related line in the sand, regretted it, relented, and ended up sharing, with her pal Albert, the best-described lunch in all of children’s literature.

In one of the great unheralded joys of parenthood, I shared my love of the book with my children, who adored it just as much as I did. In another great unheralded joy of parenthood, I got a do-over; I hadn’t known as a child that there were other Frances books, and I got to share those with my kids, too. They loved them all. I’m not saying that one of my children, now a teenager, suggested that she and I get matching tattoos of the tiny vase of violets on Frances’ lunchtime desk, but I’m not saying she didn’t.

When I heard that Russell and Lillian Hoban, Frances’s creators, were getting a show at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, I couldn’t wait to go. The Hobans’ work makes up the largest part of the exhibit, which is called The Art of Collaboration and runs through April 15. Drawn from Yale’s various collections, the show “explores the excitement and power of separate elements combining to make things that are new, beautiful, strange, and memorable” in an attempt to show that “collaboration itself is an art form.” Evidence of how difficult this art form can be is found in a smaller section of the show, devoted to unsuccessful, cringe-inducing collaborative efforts to translate Richard Wright’s Native Son for stage and screen. Other joint projects in the exhibit achieved happier results—I loved the creased-paper game of Exquisite Corpse played by Picasso and Saul Steinberg. You can’t miss it—it’s around the corner from the Gutenberg Bible, across from the huge, ravishing painted book of John James Audubon’s Birds of America that’s permanently installed on the mezzanine, next to the breathtaking, glass-enclosed six-story book towers soaring through the center of the space, which is my way of telling you that you really ought to visit the Beinecke Library.

The Frances books get their due in the exhibit, but lots of the Hobans’ other work is represented as well. The duo did 26 books together, starting in 1961. You can look at early sketches and drafts, letters between Russell and his legendary editor Ursula Nordstrom, comments on manuscripts. You can learn a bit about the duo’s life story: Both were children of book-loving, aggressively secular Eastern European Jewish immigrants. Russell’s parents ran a newsstand; his father also worked as an advertising manager for the Jewish Daily Forward and directed Yiddish theater. He died when Russell was only 12. Lillian Aberman studied dance as well as art. She trained with Hanya Holm, one of the founders of American modern dance, and with Mary Anthony, a prominent student of Martha Graham’s. (The library has footage, not on view, of Lillian dancing on TV.) Lillian and Russell met at the Graphic Sketch Club and married when they were only 18.

They soon moved to New York City to make their fortunes. Russell started a career in freelance illustration and advertising—he was an art director at BBD&O—but he never loved to draw the way Lillian did. (In 1961, the magazine American Artist said of his work, “Hoban has the analytical ability and the tenacity of a veteran mail-order executive.”) His first children’s book, for which he did both the text and the art, was 1960’s What Does It Do and How Does It Work, a look at the vehicles involved in construction, drawn in an eye-catching, wood-block-y, constructivist style. It underperformed. “No final figures on the heavy-machinery book,” Nordstrom wrote to him. “Don’t be discouraged if it didn’t sell as well as you and I hoped. It is still a noble book, and also it did bring you and Harper together.” She was right; when Lillian came on board, the publisher more than got its money’s worth.

The first Frances book, Bedtime for Frances, came out in 1960. The art was done by Garth Williams, a huge name in children’s book illustration. (He did the drawings for Charlotte’s Web and the Little House on the Prairie series.) It was he who apparently decided to make Frances a badger; the text never actually mentions her species. When Lillian took over after the first book, the look and feel of the books changed. Williams’ art is more luminous and dimensional than Lillian’s, more technically proficient, but hers is warmer, funnier, more kidlike. “She said, ‘I’m no badger master; I concentrate on getting the feelings right,” curator Elizabeth Frengel told me. Russell and Lillian’s daughter Phoebe Hoban, a journalist and author of well-regarded biographies of artists Jean-Michel Basquiat and Alice Neel, told me in an interview, “My mother managed to make a badger cuddly. And her details are so cozy and domestic, like the wood grain furniture and the little flower borders by the front door.”

Lillian had envisioned Frances as a vole; some of her early vole sketches are included in the exhibit. (“They’re bigger, and maybe more expressive?” Frengel said.) But she took to badger art with gusto. “My favorite Frances picture is the one in which she’s holding the jump rope and bread-and-jam sandwich,” Phoebe said. “You can see she’s thinking, ‘Is this what I’m in for?’ Sitting next to Albert as he eats his perfect lunch—the look of complete dismay! She just imbues these characters with human warmth and heart.” Russell was delighted to work with his wife and had no desire to go back to picture-book art himself. “Russ and I have completely different feelings about illustration,” Lillian observed in a title card quoted in the exhibit. “It was always a heavy thing for him—he used to sit at the easel groaning and yawning, and he was glad to give it up when he did.”

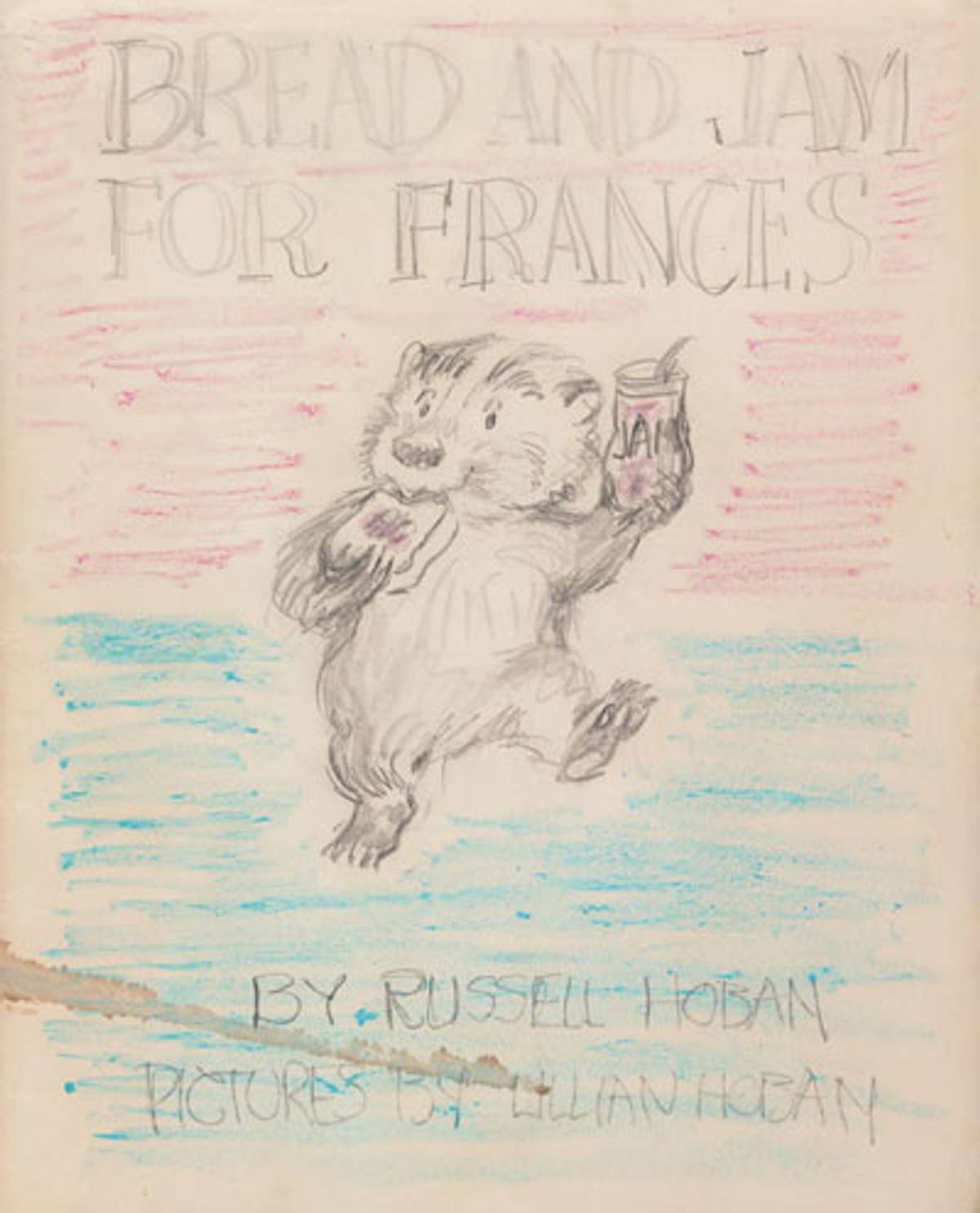

In those days, printed text was cut up into strips and pasted on pages of an artist’s dummy, also called a mock-up or maquette. At the Beinecke show, you can use a touchscreen to compare the mockup of Bread and Jam for Frances with the first printed edition. In a scene in which Frances is starting to realize the Faustian bargain she’s made, she watches her friend Albert eat his lunch.

He ate his bunch of grapes and his tangerine.

Then he cleared away the crumpled-up waxed paper,

the eggshell and the tangerine peel.

He set the cup custard in the middle of the napkin on his desk.

He took up his spoon and ate up all the custard.

Then Albert folded up his napkins and put them away.

He put away his cardboard salt shaker and his thermos bottle.

He shut his lunchbox,

put it back inside his desk and sighed.

“I like to have a good lunch,” said Albert.

Frances ate her bread and jam and drank her milk.

Originally, that page ended with two lines that Lillian moved to the following page, which in the final version reads:

Then she went out to the playground and skipped rope.

She did not skip as fast as she had skipped in the morning,

and she sang:

Jam in the morning, jam at noon,

Bread and jam by the light of the moon.

Jam…is..very…nice.

It’s much more effective to let Frances’ lunch, so sad in comparison to Albert’s, end a page, sitting there like an undigested lump of bread, rather than to end that page with skipping rope. The rope-skipping and unenthusiastic singing, too, feel more pathetic and linked when they’re together on their own page. (There are other changes, too, like the daddy badger’s glass of red wine at dinner disappearing—a note, “NO WINE,” is scribbled on the page—and becoming a pepper grinder.) Lillian’s sympathy for Frances, as well as her sense of fun, are evident throughout the book. She herself wrote, “I have just as good a time as a kid with a coloring book. I’m not a strong draughtsman, but I don’t worry about it—I concentrate on getting the right feeling in the pictures.” And she does. Frances has the most expressive eyebrows in picture books.

Russell did not always seem to be having a good time. He wanted to write for adults, and his text for The Mouse and His Child (which he labored on for four years, from 1963 to 1967) seems like a transition to his later novels for grownups. He wrote to Nordstrom, whom he called “Urse”: “I think that my metaphysical speculations are cognate with those of the current young generation,” and says, “The Mouse and His Child is a curiously valid book because a strong idea arising in this place at this time made me its medium and got itself written.” But when the book finally appeared, reviews were mixed. The New York Times disliked the way the characters spoke in “philosophic conundrums”; opined that readers care about characters, “not metaphysics”; and sniffed, “The intellectual trappings of this story are unnecessary.”

It seems clear that Russell’s heart wasn’t in Television for Frances, which was never published. An editor’s note on a (second? third?) draft at the Beinecke reads, “All of us think it is much better, but there are still a few things we think you should consider. Frances is so smart it is hard to accept the fact that she wouldn’t know the set wasn’t plugged in. Isn’t there something a little more unexpected that could be responsible for putting the set out of commission?”

Struggling with writer’s block, Russell moved the family to London in 1969. “He had this sort of literary idealization of England,” Frengel told me. In 1970, Lillian moved back to Connecticut with the kids. “The correspondence with Ursula Nordstrom ends abruptly,” the curatorial text says. Russell spent the rest of his life in England; in 1975 he married the much younger, German-born Gundula Ahl, whom he’d met in 1970 (he called her a “book siren”) and with whom he had three more children.

***

Their collaboration over, the Hobans’ literary lives continued separately. Lillian illustrated books by other noted children’s book writers—many of them other Jewish women. She did 19 books with Miriam Cohen, 12 with Joanna Hurwitz, six with Marjorie Weinman Sharmat, and two with her daughter Phoebe. She also wrote and illustrated 28 books on her own, including a popular “I Can Read” series starring Arthur, an anxiety-prone chimpanzee.

If you look at Russell’s vast web presence today, you might not know he’d ever written children’s books. A 2010 profile does not mention the picture books—or Lillian—at all; a 2016 piece discusses “a cluster of redesigned or refurbished editions of Hoban’s books,” relegating “his first wife, Lillian” to a dependent clause. The internet teems with rabid fans of Russell’s metaphysical cult novels, the most popular of which is Riddley Walker, which Hoban began in 1974 and published in 1980. A postnuclear, dystopian philosophical novel set in Canterbury in the distant future, it’s written in a fractured, fragmented language, somewhat like 1962’s A Clockwork Orange. Atomic energy is called “the Littl Shynin Man the Addom”; diplomacy is “plomercy”; the government is called “the Pry Mincer.” Another favorite is 1983’s Pilgermann, set in the Middle Ages, depicting the violent pilgrimage to the Holy Land of a German Jew who has been castrated by a mob. Hoban called it his only Jewish book. It is full of mysticism, but also Jewish humor. Pilgermann asks, “Why me?” and is told, “Why not you?” When Pilgermann cries out to God in agony, Jesus appears, and Pilgermann tells him, “You’re not the one I was calling.” The Times praised the book’s “lyrical intensity” and “quirky brilliance,” but Kirkus was more measured: “At its best: a harrowing yet elegant blend of shapely parable and anguished imagery. At its worst: a cross between a comparative theology lecture and Castaneda-style blather.” Hoban’s acolytes obviously side with the Times. On Russell’s birthday every year, they write their favorite Russell Hoban quotations on bright yellow paper (the kind he wrote his novels on) and leave them in public places all over the world. They’ve been doing this for the last 16 years.

Russell told an interviewer that climbing Masada influenced the writing of Pilgermann. “I was very much aware of what Schrödinger says that there really is just one mind, and that in that mind the time is always Now,” he said. “I remember climbing the long snaky path to Masada, and up on the top of it, in that dry, hard, stony sunlight, seeing pebbles and potshards casting sharp, black shadows; and feeling that the events that made Masada what it is were continuing to happen—that the suicide of the Zealots and the coming up the ramp by the Romans were still going on. … Everything in Pilgermann had to do with ideas of what it is to be a human particle of the universal consciousness. I have nothing to do with any organized religion of any kind. I think I’m a very religious person, but I don’t go in for anything organized, whether it’s Judaism or Buddhism.”

What he did not say was that he went to Masada because Lillian and the children were in Israel the time. Despite their estrangement, “when the 1973 war broke out, my dad came and announced he’d come to die with us,” his daughter Esme told me drily in an interview.

Lillian had taken the kids to Israel because her parents lived in Rehovot. The story, as Esme related it: Lillian’s parents had come to Palestine from Russia as young children in the early 1900s. They grew up together and married when they were around 18. In their early 20s, they went to Philadelphia so that Lillian’s father could earn money to buy agricultural equipment. He also hosted secret Zionist meetings. “My mother was a naughty girl like I was,” Esme said. “She would hide under the table so that she could listen as the adults talked in Yiddish about getting weapons and shipping them to Palestine to fight the British Mandate.” Lillian’s parents eventually made aliyah for good, and Lillian lived there from 1972 to 1975. Esme attended high school there, lived on a kibbutz in the Upper Galilee, fell in love with an Israeli, and married him in 1982.

“She was incredible, my mom,” Esme told me. “She taught me how to drive when I was home from Israel—my boyfriend had taught me to drive in the cotton fields, but I’d never driven on a road. She told me she’d never driven to New York the whole time she was married to my father. And the more I think about it, the more I realized that my mother really did take a backseat to my father. She was in the background. She made food, she made sure the house was clean, she went shopping, and she worked, and I took it all for granted. It wasn’t until my father left that I understood. She’s my hero.”

Lillian wrote a middle-grade novel, I Met a Traveler, about her youngest daughter Julia’s experience in Israel. “It’s very Jewish and very special,” Esme said. “All my pride in being Jewish came from my mother.” Like many of Lillian’s books, it’s out of print.

Lillian died in 1998 at age 73; Russell died in 2011 at 86. In the last few years, the duo’s collaborative picture books have been coming back into print. Plough reissued 1966’s Charlie the Tramp (about a beaver with wanderlust: “You never know when a tramp will turn out to be a beaver”) in 2016, and 1969’s Harvey’s Hideout (about muskrat sibling rivalry: “That is because you are a loudmouth, bossy, mean and rotten big sister,” said Harvey”) last month. Doubleday reissued 1971’s beloved Emmet Otter’s Jug-Band Christmas (which you may also remember as a Jim Henson TV special) this past October. More, more, more, publishers!

Thankfully, the Frances books have never left us. When I told my agent I was writing this piece, she grabbed my arm and asked, “Do you want to be careful, or do you want to be friends?”—a line from A Bargain for Frances, a brilliant look at complicated friendships and savvy sisters. “The books embody this really authentic, distilled essence of family dynamics,” Phoebe said. “They’re about the things every family encounters. They’re universal. My mother’s very warm and human pictures express that humanity.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.