Back to School

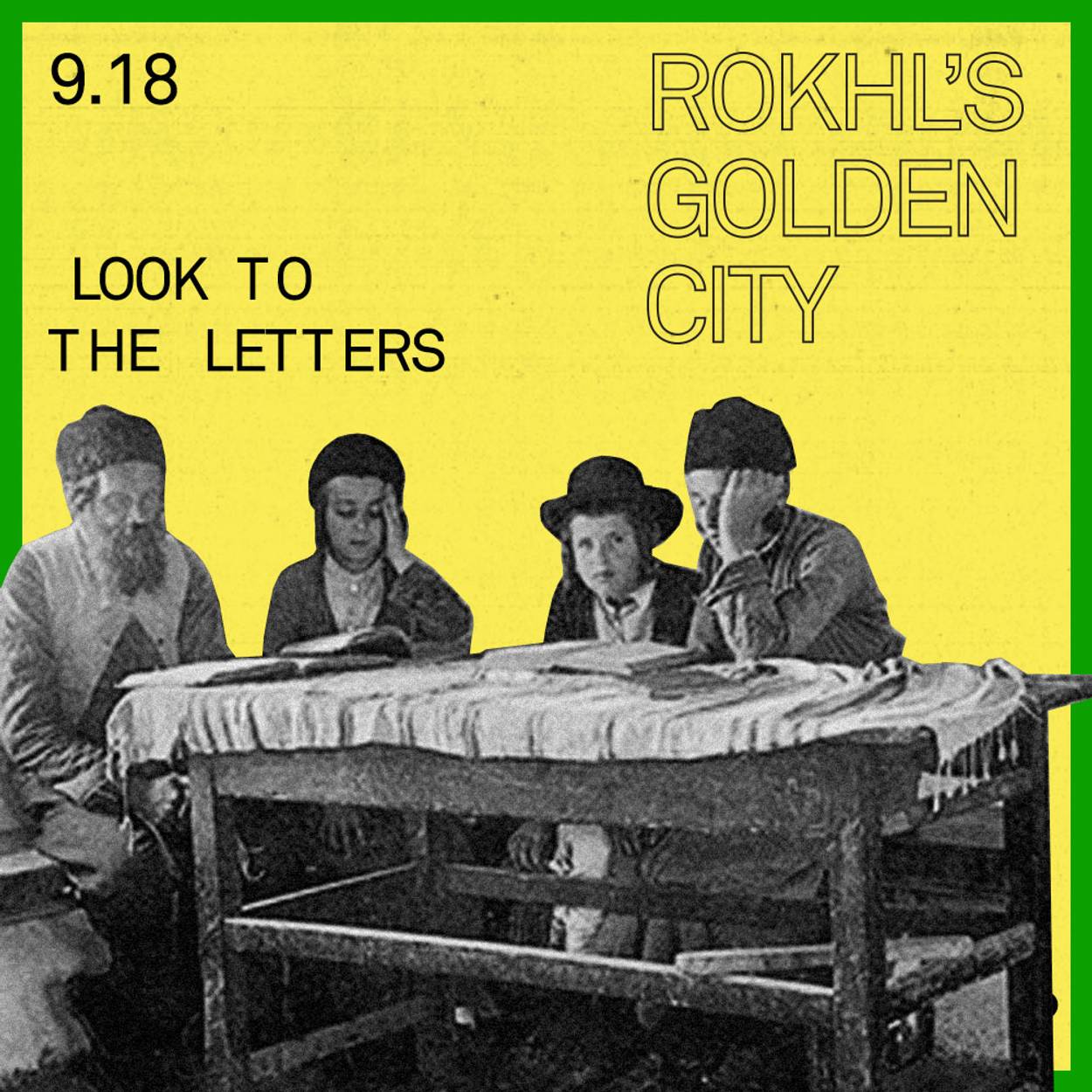

Rokhl’s Golden City: Remembering the warmth—and the trials—of the old Yiddish ‘kheyder’

I’ve probably already said too much about my own undistinguished academic career. Not unrelatedly, I hated school, and did my utmost to attend as little as possible. A decade before I started there, part of my middle school was burned down by a couple of students—possibly the only fond memory I have of that particular institution, and it’s not even my own.

In the Old Country, though, the schoolroom fire meant warmth and coziness, not arson—at least, according to one of the most famous Yiddish songs of all time, “Oyfn Pripetshik” (At the Hearth). Though written and published under his own name in 1900, Mark Warshawsky’s “Oyfn Pripetshik” was quickly taken up as a “folk” song. Oyfn means at or by; pripetshik refers to a hearth, stove, or fireplace. In the song, a teacher or “rebbe” is teaching the alef-beys to students in a kheyder (one-room school). The pripetshik is functional, of course, heating the room, but in the song, it’s also meant to evoke the ner tomid, eternal flame, of the Temple, and a symbol still found in synagogues around the world today.

Az ir vet, kinder, dem goles shlepn,

Oysgemutshet zayn,

Zolt ir fun di oysyes koyekh shepn,

Kukt in zey arayn!

As you children endure the Exile

You will become exhausted

So you should draw strength from the letters

Look to them!

I was going to begin here by saying how utterly weary I am of “Pripetshik”: its ubiquity, its grating, saccharine melody, and, most frustratingly, its recent association with the Holocaust, via Schindler’s List. But before I get to the cynicism, I am duty bound to honor the corn. I learned “Oyfn Pripetshik” during my first semester of college Yiddish, a time when I was, quite literally, relearning the Hebrew alphabet, the oysyes (letters) of the song. Like the students in the song, I was becoming acquainted with the sounds of Yiddish: komets alef oh. “Oyfn Pripetshik” was part of my life-changing lightbulb moment, when I realized that the oddball vowels of my father’s Hebrew weren’t weird or wrong, they were, in fact, important enough to have been memorialized in one of the greatest hits of Jewish history.

Furthermore, goles (exile) wasn’t just some imaginary, timeless shtetl, it was also Kyiv of 1900 and Long Island of 1980 and Brandeis of 1990-something. Warshawsky was a sophisticated Kyiv lawyer, product of the Haskole (Jewish Enlightenment) and good friend of none other than the avatar of modern Yiddish literature and self-reinvention, Sholem Aleichem. Warshawsky was writing about the kheyder from a great distance; this was an institution he believed was, and should be, disappearing. This is all to say that “Oyfn Pripetshik” is a song that demands a certain amount of contextualization, but is most often treated simply as an authentic ethnographic text.

Consider that in 1880, my spiritual zeyde (grandfather), the historian Shimon Dubnov, said of the kheyder of his youth that “a crime is committed there: the massacre of innocents.” The maskil Isaac Ber Levinsohn called it a “classroom filled with death.” The great Yiddish and Hebrew writer known as Mendele Moykher Sforim (Sholem Abramovich) said that kheyder boys are “like sheep led to the slaughter.”

All of the above (and more) are quoted in Steven Zipperstein’s excellent study, Imagining Russian Jewry: Memory, History, Identity. Looking at the contemporary journalistic and institutional accounts of the day, Zipperstein describes how the kheyder as a Jewish national institution was under furious attack from reformers of various kinds. But, because of the kheyder’s ubiquity and efficacy in transmitting deep Jewish literacy in a compressed amount of time, there was a tremendous amount of anxiety about its disappearance. At the moment Warshawsky published his tribute, Zionist reformers were celebrating the rise of the heder metukan (reformed kheyder), with 900 new Hebrew-in-Hebrew schools constituting 10% of registered khadorim. These new schools challenged the seemingly ancient pedagogical method to which “Oyfn Pripetshik” alludes: taytsh, or rote translation of loshn-koydesh (Hebrew-Aramaic) texts into Yiddish. The song says, “ver s’vet gikher fun aykh kenen ivre/der bakumt a fon” (he who learns Hebrew fastest will receive a prize). Keep in mind that in Yiddish, zogn [speaking] ivre means to be able to read loshn-koydesh out loud, not use it conversationally. Knowing and “speaking” ivre in the kheyder context was still a matter of rote learning.

The greatest threat to the kheyder wasn’t Zionism, however, but the world of European culture at large, embodied best in the seductive appeal of Russian Romantic literature. It was via Russian novels that Shloyme-Zanvil Rapoport transformed himself into Semyon Akimovich An-sky. An-sky left his home to work as a tutor for Jewish boys, with the explicit intention of leading his students away from traditional life. Though most didn’t go to An-sky’s extremes, his story of rejection and return was fairly typical.

As Sheila Jelen notes in Salvage Poetics: Post-Holocaust Jewish Folk Ethnographies: “at the inception of modern Hebrew and Yiddish literature in the late nineteenth century, largely in the forms of memoir and bildungsroman, the cheder story is central. The most frequently told narrative is one of childish intrigue and rabbinic cruelty, wherein the spirited and intelligent youngster is beaten into submission by an unintelligent and impoverished teacher.” The protagonist must break away from the world of the kheyder in order to enter the larger world of “literary endeavors.”

The violence and cruelty of the kheyder was hardly an invention of those aggressively leaving it behind. “[T]he kheyder had to be run by a combination prison guard, exegete, and child psychologist,” writes Michael Wex in Born to Kvetch. “But we’re in goles; we got the melamed [kheyder teacher] instead.” Wex goes on to enumerate the many forms of corporal punishment found in the kheyder, known collectively as matnas yad, gift of the hand. These include the knip (pinch), patsh (slap), and zets (blow), but it’s worth picking up Wex’s book to appreciate the whole symphony of pedagogical violence endured by (mostly) boys from the age of 3.

For me, the cozy fire of “Pripetshik” is most definitively doused by an anecdote told by the Yiddish activist, writer and pedagogue, Itche Goldberg. His family was living in Warsaw right before WWI and his father was already gone to Canada. Young Itche was deemed clever enough to fend for himself, as well as to find a place in a school somewhere. He ended up at a kheyder with a rebbe who was coarse, but who doted on him. One day the rebbe invited Itche and four other boys to accompany him to the bathhouse, where they would assist in bathing him. When Itche hesitated to touch the rebbe down there, he urged the boys on: “vash, vash, dos iz oykh an eyver” (wash, wash, that, too, is a limb). Some nine decades later in an interview, Goldberg recalled this awkward encounter with aplomb, noting that he never, ever returned to kheyder. (Ironically, he ended up at a Zionist-oriented teachers’ seminary after that, before eventually becoming an icon of the American Yiddish Communist movement.)

The methods of the kheyder were effective, but, shall we say, deeply problematic. Sholem Aleichem had his own singable take on the kheyder experience. I’ll never forget the first time I saw it performed, brilliantly, by my friend Shane Baker, as part of his Yiddish vaudeville show. He was dressed as the vaudevillian Ludwig Satz, an adult man in short pants and peyes, sobbing in dread:

Kh’vil nit geyn in kheyder

Vayl der rebe shmayst keseyder,

Un der kantshik dresht di beyner,

Lernen ober vil nit keyner–

Kh’vil nit geyn in kheyder

I don’t want to go to kheyder

because the rebbe whips us.

The whip hurts our bones,

And no one wants to learn anyway—

I don’t want to go to kheyder.

My friend Miryem-Khaye Seigel performed a gender-bending version for a recent tribute to Sholem Aleichem. With its perfect mixture of horror and absurd comedy, the song reminds us to be ever alert to the complexities of our ancestors, and our history.

ATTEND: Childhood, children’s literature, and the changing nature of Jewish education will all be on the agenda on Oct. 7 when we celebrate the launch of Miriam Udel’s new book, Honey on the Page: A Treasury of Yiddish Children’s Literature. I’m honored to be moderating a discussion about the book, joined by Naomi Seidman and Jennifer Young. Tickets here.

LISTEN: I love Miriam Kressyn’s heartbreaking version of Mordkhe Gebirtig’s “Motele.” In the song, a father and son exchange words about the son’s behavior in kheyder. The rebbe says Motele is misbehaving. Motele insists that it is the rebbe, not Motele, who is in the wrong, for beating him black and blue.

MORE: Natalia Aleksiun and Samuel Kassow will speak virtually on “Conscious History: Polish Jewish Historians Before the Holocaust” on Sept. 22, tickets here … On Sept. 30 the good folks of Gefilteria are giving a demonstration of traditional cooking for Sukes/Sukkot called “Comeback Cabbage” and it sounds absolutely amazing … In my last column I noted how American Pickle’s Herschel Greenbaum would have been among the last Jews to make it into the United States before the draconian new immigration laws of the early 1920s essentially cut off entry to all Jewish immigrants. On Oct. 1, the Yiddish Book Center will present a talk by Eddy Portnoy, about the reaction of the Yiddish press to the new immigration restrictions. Register here … On Oct. 6 join composer and Pulitzer Prize finalist Alex Weiser for a conversation on “The Yiddish Art Song: Creating and Curating for a New Generation” … Join In Geveb founding editor Saul Zaritt as he celebrates the launch of his new book, Jewish American Writing and World Literature: Maybe to Millions, Maybe to Nobody. On Oct. 15 he’ll be in virtual conversation with Sunny Yudkoff and Adriana Jacobs … One of my very favorite writers on Yiddish-American history, Tony Michels, is going to be talking about the Jewish encounter with race and racism in the United States. On Oct. 22 he’ll give a talk called “The Yiddish Press and Racism in America: 1880-1920.” Register here … I know this is far outside my usual lane, but I’m going to recommend this lecture from 1975 on the tshuve (repentance) of Rosh Hashanah. The speaker is Rabbi Soloveitchik (the Rav), late rosh yeshiva of Yeshiva University, and one of the most important shapers of modern Orthodoxy in the United States. He speaks in a strong Litvish Yiddish, with interesting lapses into English here and there. The content is highly compelling and appropriate to the season, obviously, but it’s also just fascinating to hear his Yiddish. You can follow along with the English subtitles, as necessary.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.