Behind the Curtain

The recently demolished Seattle Curtain factory held a century’s history for the city’s Sephardic community—and for the family that founded the business after immigrating from Rhodes

Any Seattle resident will grouchily tell you that the Emerald City is changing: The regional housing market is the hottest in the country, roads are clogged by Tesla-driving techies, and local businesses are being shuttered by Targets. Embodied by the futuristic Amazon Spheres, Seattle’s entrepreneurial and technological boom has wrought an amazing transformation in areas like South Lake Union and the downtown core, which has been eerily quiet during the past year of COVID-induced lockdown. Enormous cranes have joined the iconic Space Needle in the skyline, hovering like the crows menacing our exurban picnic tables. Beloved landmarks like the Elephant Car Wash are gradually falling, their neon signs shipped off to museums as relics of a grittier, funkier era.

From this perspective, the recent demolition of the Seattle Curtain Manufacturing Co. on East Yesler Way is just another symbol of the rapidly changing urban landscape. The family-run company produced custom textiles for nearly nine decades, turning a profit particularly from contracts with Seattle hotels and department stores. However, the property’s sale in 2019 and teardown earlier this year as part of a Central District development deal symbolize more than another local business whose time was up; it is also the end of an era for a beloved institution in the country’s third-largest Sephardic Jewish community.

When pictures of the building’s rubble appeared on Facebook in mid-January, a communal outpouring of nostalgia erupted. Someone posted a black-and-white photo of an employee picnic, nine women in pinned curls and pearls, grinning at the camera. Commenters recalled the weekly Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) class that was taught in a corner of the showroom during the business’s later years, giving many a new connection to their ancestral tongue. Some people posted snippets about the neighborhood known as the Kosher Canyon, the original commercial and religious heart of Seattle’s Jewish community, bound by East Cherry Street to the north and East Yesler Way to the south. Between the 1920s and the 1960s, this vibrant corridor of kosher butchers, bakers, and grocery stores offered everything from special Purim candies to arroz molido, the finely ground rice used to make sutlach, a sweet rice pudding beloved by the many Ottoman Jewish immigrants who resided nearby. On Rosh Hashanah kids would synagogue-hop among the different houses of worship lining East Fir Street, before the two Sephardic synagogues moved south to the neighborhood of Seward Park and nestled near the shores of Lake Washington.

As I began asking people to share their memories of Seattle Curtain in greater depth, I realized that here was a story of a uniquely Sephardic and American space that lasted almost a full century.

During its long lifespan, Seattle Curtain—known to the community simply as “the factory”—witnessed these and other changes in Seattle’s Jewish orientation points, yet the company’s founding principles remained the same: Work hard, treat employees like family, honor your religion, and give back. As I began asking people to share their memories of Seattle Curtain in greater depth, I realized that here was a story of a uniquely Sephardic and American space that lasted almost a full century.

Raphael “Ralph” Capeluto and Rachel “Rae” Alhadeff both emigrated from the Mediterranean island of Rhodes to the United States in the early 20th century. Ralph had spent his initial years in New York, first washing windows and later becoming a mechanic at bra, curtain, and hat factories. He met Rae on a visit to see family in Seattle, and they wed shortly thereafter, in June 1930. The real impetus for starting the curtain factory came from Rae, who had graduated from Seattle’s Garfield High School and attended business school. She knew that Seattle lacked a curtain factory, and a meeting with local department stores confirmed her hunch that custom curtains would be an excellent niche to fill. After a trip back east to purchase materials, Ralph and Rae opened Seattle Curtain Manufacturing Co., serving as company head and bookkeeper, respectively. Their first production space and showroom was in the Prefontaine Building at 3rd and Yesler, located near Seattle’s historic Pioneer Square.

Over the course of four generations, the business made its mark on Seattle’s growing economy, the two neighborhoods where it was located, and the Sephardic community. Many Sephardic women, with last names like Cordova, Ferrera, and Hasson, would work there loyally for years; some had been hired while still living on Rhodes to help boost their immigration applications. It was the kind of place that would offer a summer job to any teenager who needed one. Eventually, the staff expanded to include a cross section of Seattle’s working class, with African American and Asian American employees working on the production floor and as seamstresses.

This reflected the diverse ethnic makeup of the early-to-mid-century Central District, said historian Devin E. Naar of the University of Washington, describing how restrictive covenants shaped Seattle’s neighborhoods by determining where minority groups could and couldn’t live. As a result, Naar observed, the story of Seattle Curtain Co. is part of a more complex “history of racism and exclusion in the city despite which communities could nonetheless carve out spaces that were theirs.” The business’s Jewish identity was always integral to its operation: The factory closed for Shabbat and the Jewish holidays, and workers exchanged Ladino expressions on the floor. As one former employee recalled, “The Capelutos liked the mix of cultures, but also maintaining who they were.”

Ralph and Rae had four children, and their son Morris eventually took over the factory’s day-to-day operations. Morris, known as Morrie, was a gifted salesperson who cared deeply about his employees and customers—a true benadam, to use the Ladino equivalent of the Yiddish word mensch (both convey a person’s essential goodness and moral uprightness as a human being). Like his father, Ralph, he was a magnanimous man who fostered an atmosphere of camaraderie in his business. Morris served as president and assistant hazan of Congregation Ezra Bessaroth, the historic worship space of Seattle’s Rhodes-descended Jews, where he chanted the Book of Jonah in Ladino on Yom Kippur. He was also a talented trumpet player who went to high school with the legendary music producer Quincy Jones, remaining friends for years.

Morris’ daughter Linda Capeluto worked in sales at the factory in recent decades and has fond memories of the “home away from home” where the family would often host big holiday meals. When she visited her Papoo (Ladino for “grandpa”) Ralph at work, he would sit her on a table next to piles of curtain rings: “My grandfather taught me to put the rings on my fingers, and then drop them into the bag. He would give me a penny for each bag that I filled correctly.” She remembers the party when Seattle Curtain’s new building was inaugurated in the 1960s, at the corner of Yesler and 12th Avenue South, on the southwestern periphery of the Kosher Canyon. The factory took up two stories, with the office space and showroom below, and the production space above. Linda’s brother Ralph—named after his grandfather while he was still alive, in accordance with Sephardic tradition—said of his siblings, “We grew up in those buildings.” Once he was old enough to work there full time, the younger Ralph was “usually the first one in and the last one out.”

David Behar was one of the local boys who had a summer job at Seattle Curtain in the early 1970s. He jokingly refers to himself as a hamal (the Arabic-derived Turkish word for a porter) when he recalls bringing up bolts of fabric from the basement. After earning his stripes, Behar worked on the grommet machine, then graduated to installation, which meant taking the company truck to deliver finished products. In addition to curtains, Behar notes, the factory created wraparound vinyl coverings for the sukkah walls at local residences and synagogues. “Papoo Ralph was there every day,” he told me. “The factory was like a family.” The older Ralph Capeluto died in 1984, followed by Rae in 1994; the family would continue running the business for another 20-plus years.

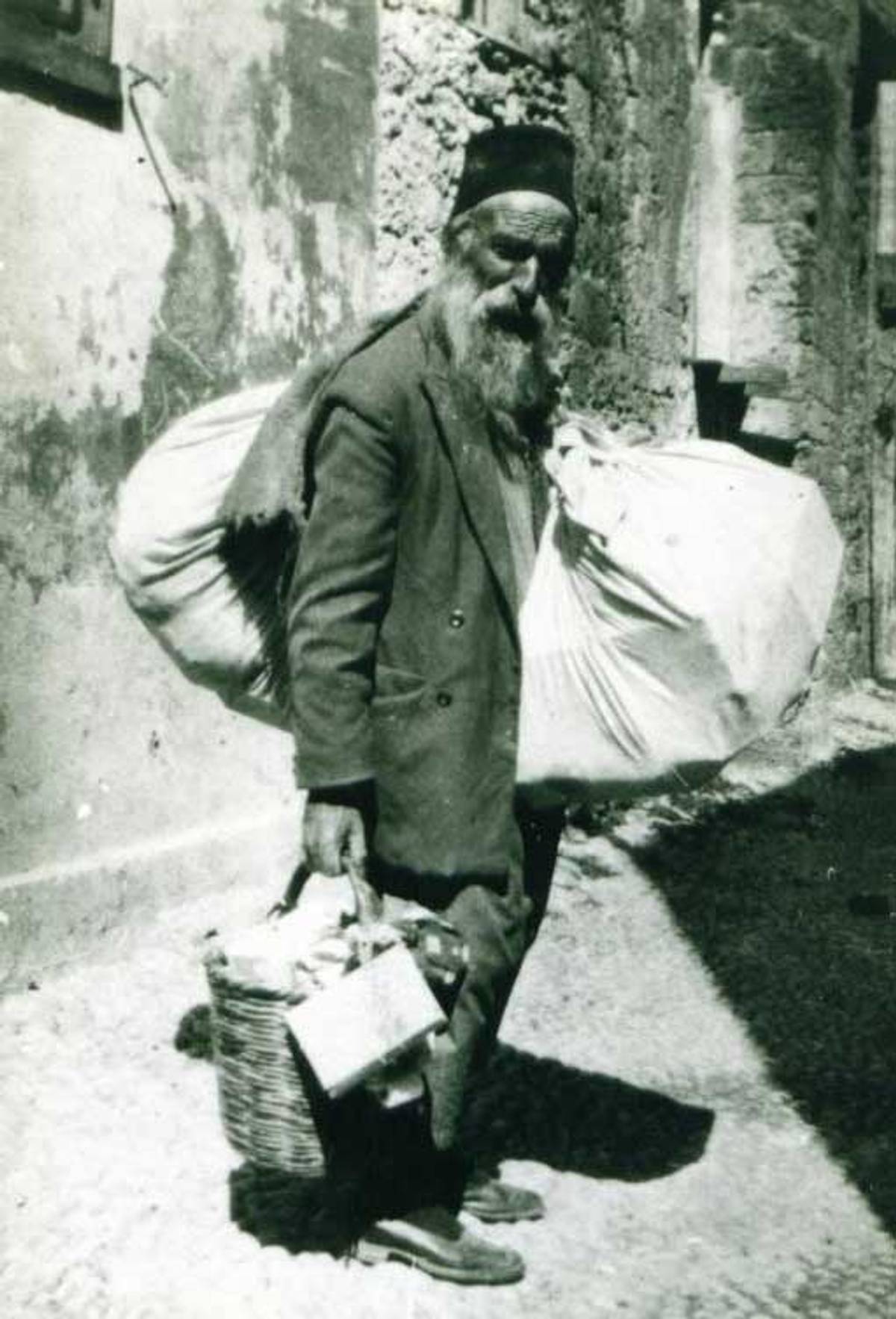

Many of those I spoke with recalled that in the business office hung a picture of Ralph Capeluto’s father, a man named Mussani (the Ladino version of Moshe), taken in the 1920s on the island of Rhodes. Mussani sold notions—pieces of fabric, lace, and other sewing supplies—which he packed in bags and carried door to door. The photo shows him standing on a street paved with the ubiquitous small pebbles that Sephardic Jews called piedras, wearing a square cap and hoisting bulky bags on either side. Mussani was a direct contemporary of my great-great-grandfather Samuel Leon, a winemaker who ran a café in La Juderia, the Jewish quarter. Maybe they used to share a raki together at the end of the day, before Samuel rode off on his donkey to check on his vineyards. Mussani’s gravestone, searchable in the Rhodes Jewish Museum’s online archive, bears a picture of a pair of scissors.

“It’s no accident that Ralph went into the textile business,” said Rena Hoffman Behar, another Capeluto granddaughter. Not only was there the example set by the hardworking Mussani, but, she explained, “Ralph always valued meticulous craftsmanship and attention to detail. He told me that the skillful packaging of Japanese goods imported to Rhodes made a big impression on him as a young man.” This belief in maintaining high standards of workmanship carried over into his custom curtain business in America. Behar, who was the first to post the photo of the demolished building on social media last month, sees the transition as a sign of the city’s “startling change in land use and economic fabric”—pun not intended, but quite fitting—that has shifted the focus from niche industries that supported plane-building and ship-making almost entirely to technology.

Seattle Curtain helped community members connect with the bedrock of their Sephardic heritage: the Ladino language.

What is the legacy of a business like Seattle Curtain in the era of globalization, Amazon, and big tech? At first glance it may seem that the factory’s impact was profoundly local, but this is not entirely the case. In 1930 Ralph began to receive letters from his sister’s 9-year-old daughter, Claire Barkey, who was still living on Rhodes along with many Capeluto relatives. Over the next 16 years, they would continue corresponding as the situation for Rhodes’ Jews increasingly deteriorated. By 1938 racial laws were imposed by the island’s Italian colonial rulers, who had allied with Germany. This culminated in the deportation of Rhodes’ Jewish population in July of 1944 and the near-annihilation of the entire community during the Holocaust. Leveraging every financial and political apparatus at his disposal, Ralph saved Claire and eight other family members from this perilous fate, as well as the families of two of his other sisters on Rhodes. By wrangling with consulates, banks, and refugee organizations, he helped them flee to Tangier, Morocco, in 1939, where they lived out the duration of WWII. Ralph then navigated all the bureaucratic hurdles necessary to acquire visas and bring the Barkey family, finally, to America in 1946.

Memos typed neatly on Seattle Curtain letterhead, whose logo featured Chief Seattle within a ruffled curtain, appear in Cynthia Flash Hemphill’s edited collection A Hug from Afar, alongside family letters translated from Ladino, telegrams, archival photographs, and other documents demonstrating the American immigration system’s complexity at that time. The compendium is an amazing sourcebook proving Capeluto’s determination to save his relatives as well as their will to survive. Asked about what the factory meant to her family, Flash Hemphill said, “The Barkey family is forever indebted to Uncle Ralph and Aunty Rae for their efforts to save them from the Nazis during the Holocaust. There is no way they would have succeeded without the proceeds from the business, the community connections, and their desire to really help these relatives who lived so far away.” She estimates that there are hundreds of descendants alive today because of the Capelutos’ lifesaving actions.

Given the role it played in helping Rhodesli Jews escape the dangerous wartime situation, it is perhaps ironic, or maybe even kismet (the Turkish word for destiny), that in its last years as a business, Seattle Curtain helped community members connect with the bedrock of their Sephardic heritage: the Ladino language. Beginning in 2000, Aryeh Greenberg offered a class on the Me-am Lo’ez, a Sephardic biblical commentary first published by Rabbi Ya’akov Huli in 1730. (Notably, since it was written in the Ladino vernacular, Me-am Lo’ez was more accessible to Sephardic women than Hebrew commentaries, thus making it comparable to, though not exactly like, the Tsene-rene editions that had begun appearing in Yiddish over a century prior.) Morris Capeluto agreed to host the class at the factory, and as word spread, the group grew to include about 25 regular participants. They would continue studying together in various configurations with a succession of teachers for two decades, coming to be known as the Ladineros. Most recently, the eminent Seattle hazan Isaac Azose convened the class at the Jewish retirement facility on First Hill, where many of the participants now live. They stopped meeting only when the coronavirus pandemic put an end to in-person gatherings last year.

Greenberg, who is not Sephardic, grew up in Ezra Bessaroth synagogue, where his father was the rabbi for almost 30 years. He studied Sephardic hazanut with Azose and is now a Judaics teacher and private tutor based in Stamford, Connecticut. Greenberg saw the class as a way to improve his own Ladino while also showcasing a classic Sephardic source that, he felt strongly, participants would love if taught with the proper contexts. Many of Greenberg’s students were first- and second-generation Americans who could remember their high school Spanish teacher calling Ladino “junk Spanish”; back then, most immigrant parents, proud to be American, encouraged their children to speak English as much as possible. Now, as participants parsed the Rashi letters of printed Ladino, “the language started coming back to them,” in the words of the younger Ralph Capeluto. After the group studied for an hour and a half, it was Ralph who would set up refreshments so that everyone could linger and echar lashon (chitchat, literally “to throw the tongue”). The treats varied from yaprakes (stuffed grape leaves) to lokum (Turkish delight) and local candies like Aplets & Cotlets or Chukar Cherries. Greenberg admits that he didn’t plan on the warm community that developed among the students; quite simply, “it was magic.”

Lilly DeJaen decided to attend the class at Seattle Curtain in the early 2000s because, as a recent retiree, she was looking for interesting things to do. DeJaen’s parents both emigrated from Turkey—her mother from Marmara, her father from Tekirdag—and they belonged to Sephardic Bikur Holim, the synagogue founded by Seattle’s Turkish Jews. DeJaen lived in six different houses in the Central District growing up and can remember the era before Seattle had ZIP codes. Now 91, she reflected on her time at the factory: “Where else would we have gotten this? Everyone had given up Ladino as old-fashioned.” Even more than the meaningful content, though, DeJaen values the class as “a coming together. Everybody was welcome. It didn’t matter if you were observant or not observant, what level of knowledge you had. It was brother- and sisterhood.”

Lilly and I spoke several times as Seattle’s gray January turned to even grayer February. Through her memories, the vibrant era of the Kosher Canyon came to life: “The old neighborhood was wonderful. My mother used to say [of moving from Turkey to Seattle], ‘I left a village and I found a village.’ And the Ladino class, it was a village for us, too.”

At first glance it may seem that the factory’s impact was profoundly local, but this is not entirely the case.

When you see the angled rows of ruffled fabrics adorning the Seattle Curtain showroom in archival pictures, what you see is a vision of America. These are the type of pleated, tied-back curtains that would adorn the windowsill of a sparkling kitchen through which, in a classic ’50s television show, an aproned, manicured housewife would watch her children playing in the backyard while she prepared a casserole, smoked a cigarette, or called her neighbor. The kind of small upgrade that could make any house prettier, whether it was a small Craftsman or a mansion overlooking Lake Washington. The kind of home decor that hardworking Seattleites would purchase at the Bon Marché, hoping to spruce up this or that room. The Capelutos’ curtains were part of their customers’ strivings toward a measurable vision of fineness and beauty, a partial- or full-length realization of their American dream. From the familial notion of selling notions on Rhodes grew an extraordinary business capable of fulfilling domestic desires for a home, but also, a business that could grant a homeland to imperiled kin.

One of Seattle Curtain’s largest clients used to be Frederick & Nelson Department Store, itself a fascinating tale of ingenuity and commercial success from its inception in 1918. After the company closed in the early 1990s, Frederick & Nelson’s downtown building at 5th and Pine became the flagship store for Nordstrom, another of Seattle’s immigrant-founded family companies. Formerly beloved department stores across the country are confronting the dizzying consumer Eden offered by Amazon, whose spectral, spherical presence hovers over everything in this town. In the wake of Jeff Bezos’ recent announcement that he is stepping down as CEO, chatter is turning to Blue Origin, Bezos’ space exploration company located in the southern King County city of Kent. Maybe in a few decades Seattle will be known for building rocket ships and launching crews to colonize Mars, a turn of events that would surely please the team who designed the groovy Space Needle for the 1962 World’s Fair.

Wedged between mountains and sea, constantly perched atop cresting waves of change, Seattle has a stubborn habit of remaking itself. That pattern is likely to continue as ever more immigrants arrive at these green hills seeking their fortunes. No matter what boom beckons to them, though, the existential heart of Seattle’s Sephardim beats on, with renewed vigor for preserving and transmitting Ladino to new generations. Morris’ daughter Linda, hoping to pass on her family’s heritage, sings Ladino romansas (medieval ballads) as she bakes with her grandchildren. Thinking about all that her family achieved through Seattle Curtain Manufacturing Co., she expressed a deep sense of appreciation: “It gave us a life where we could be who we wanted to be.” For his part, Naar hopes that (post-pandemic) a new shared space will emerge for the communal study of Ladino, somewhere you could order “some bourekas with a Turkish coffee, or maybe a glass of raki after work”—a 21st-century, Pacific Northwest version of my great-great-grandfather’s café on Rhodes.

When the building at 12th and Yesler came down in January, the factory’s textured history did not disappear with it. The downstairs area where the staff celebrated birthdays and the Ladino class chatted, the production floor where sewing machines and grommet makers hummed industriously, the office where Mussani Capeluto’s photograph hung—yes, those physical spaces are gone, along with the Ethiopian restaurant and the auto shop that adjoined the factory. Gone, too, are five of the six houses where Lilly DeJaen lived during her childhood in the Central District, devoured by Seattle’s insatiable appetite for the new. DeJaen declared circumspectly, “A lot of the places where we lived have disappeared, but the memories are there.”

And now they are here, too.

Hannah S. Pressman is currently at work on Galante’s Daughter, a memoir connecting her Sephardic family history to explorations of American Jewish identity.