Books that bring smiles to both children’s and their parents’ faces are always welcome, but perhaps never more so than now.

The list of this year’s best Jewish children’s books includes stories set in modern Israel, 12th-century China, and, of course, the early-20th-century Lower East Side. Stories about relationships with friends and parents and bar/bat mitzvahs continue to be popular. This list also includes one middle-grade book about a Mizrahi community and its displacement, and I suspect we’ll be seeing more of those in the future.

But ultimately, this is the year of the midrash. While Jewish picture books still cover holidays and Bible stories themselves, there were quite a few that retold or created new midrashim—stories that expand upon missing details in the Tanakh.

Here are the best Jewish children’s books of 2023, starting with those for the very youngest readers and working our way up.

Many parents who have attended tot Shabbat with their little ones will be familiar with the mnemonic to remember the word Sh’ma: shhhh, mmmm, ahhh. Rabbi Alyson Solomon expands on that to create soothing nighttime scenes in Listen, Sh’ma. Racially diverse families quiet down with bathtime and stories (shhh), cuddle close (mmmm), and relax to fall sleep (ahhh). Cozy illustrations by Bryony Clarkson make this a reassuring bedtime book.

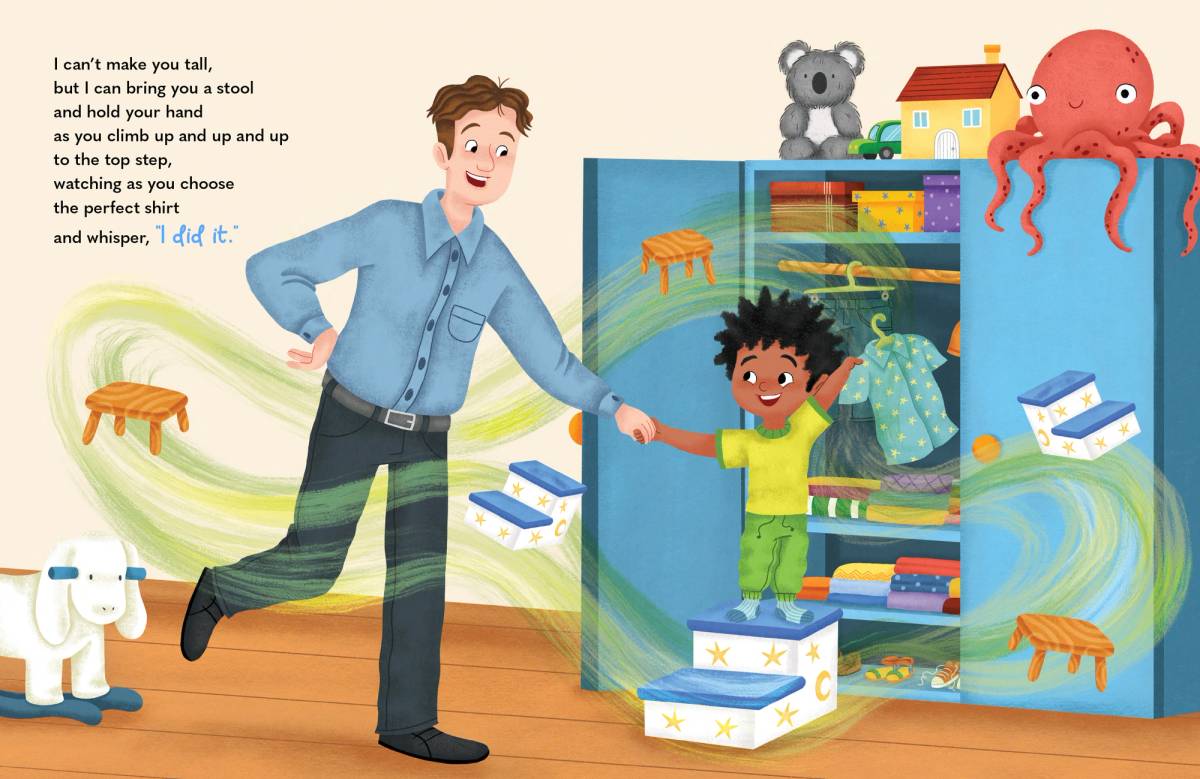

Daddy, Can You Make Me Tall? by Rona Milch Novick focuses on the Jewish value of teaching our children to be independent. A child asks his parents for help getting ready for Shabbat, but rather than do things for him, they enable him to do things for himself. No one can make a small child taller, but his father can give him a stool. Rather than find his comb, his mother teaches him how to look for it. The illustrations by Ana Sebastian depict a white father and dark-skinned mother; an adorable dog completes this family. An empowering read.

From ‘Daddy, Can You Make Me Tall?’ by Rona Novick, illustrated by Ana Sebastian Apples & Honey Press

Challah Day! by Charlotte Offsay follows a family as they make challah. The jaunty tone is set in rhyme and matched by the appealingly goofy illustrations by Jason Krischner that show the family dog and babies “helping.” With a recipe included at the end, this is the perfect book to read while your challah rises.

In Dream Big, Laugh Often and More Great Advice from the Bible, Hanoch Piven’s iconic collages accompany short retellings of classic Bible stories with Aesop’s Fables-like morals written by Piven and Shira Hecht-Koller, with Naomi Shulman. From Eve, whom Piven depicts with a head full of math, letters, and other objects, we learn to “be curious”; from Sarah, whose mouth is made of bells, to “laugh yourself silly”; and so on. While people may disagree about some of the lessons the authors take from these stories, they will certainly provide food for thought, which is exactly what good literature, including children’s literature, should do.

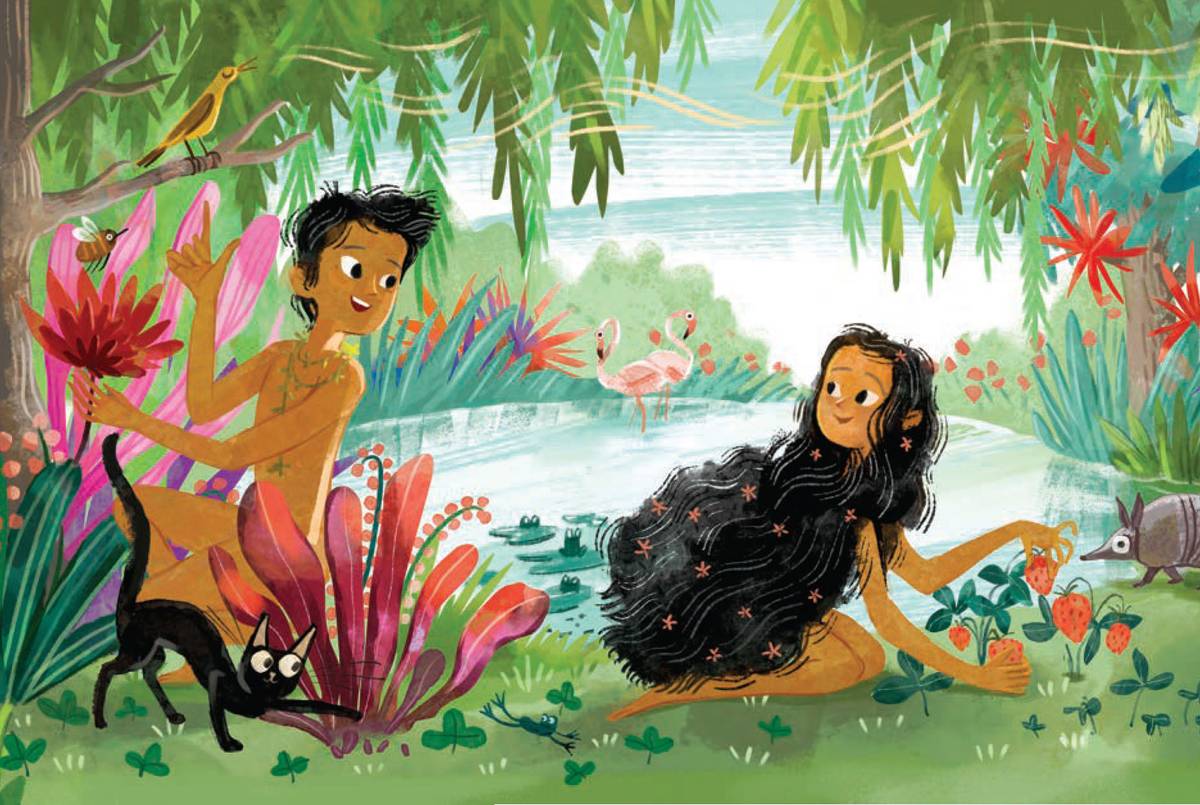

Midrash, which Leslie Kimmelman explains in the front matter of her book Eve and Adam and Their Very First Day, is “the ancient Jewish tradition of studying and filling in the gaps of Bible stories.” And it is on a roll this year in children’s books. Kimmelman interprets the creation story through a feminist lens, starting with the book’s title, which names Eve first. With appropriately lush illustrations by Irina Avgustinovich, the (nearly) fearless Eve and more anxious Adam “discover new miracles all day long.” But when the sun sets, even Eve gets a little worried. She maintains her optimism and her faith, and is proven right when the sun rises again.

Jacqueline Jules does not create her own midrash but retells one in her sweet book, Moses and the Runaway Lamb. As in the original, Moses searches for a lamb that has left his flock. He finds that she was thirsty and looking for water. After letting her drink, he realizes that she was tired after her travels, so he carries her home. As Jules writes, Moses “realized that every animal in his flock was important to him.” Not only is that why Hashem chose Moses to be the leader of his people, but the analogy between Hashem and his flock—the Jews—is clear. Eleanor Rees Howell’s pastel illustrations complement the quiet mood of the story perfectly.

From ‘Eve and Adam and Their Very First Day,’ by Leslie Kimmelman, illustrated by Irina AvgustinovichApples & Honey Press

The midrash theme continues with Counting on Naamah: A Mathematical Tale on Noah’s Ark, by Erica Lyons. Lyons reimagines Naamah, Noah’s wife, as a mathematician who uses her skills to design and plan the ark. Filled with mathematical puns and cheerful illustrations by Mary Reaves Uhles (try to find the duck on every page!), this is a fun read.

Jewish books set on the Lower East Side are a dime a dozen but Laurie Wallmark’s Rivka’s Presents is a worthwhile addition to the genre. It is 1918, and Papa is sick with the flu which is spreading worldwide. Rivka, who had been so looking forward to starting school, is heartbroken when she is told that, because of her father’s illness, she is needed at home to tend to her baby sister. But Rivka comes up with a plan: She offers to help various local shopkeepers, as long as they let her bring her sister along, in exchange for lessons. Papa recovers slowly but when he is finally well enough, each of Rivka’s “teachers” brings her a gift for her long-awaited first day of actual school. Of course, the real gift they gave her was an education. Warm illustrations by Adelina Lirius bring this period just over a century ago to life, and the variety of spreads, from double-pages to spot illustrations, keep the story’s momentum going. Children who lived through the recent COVID-19 pandemic will be all too familiar with the disruption to Rivka’s schooling—and may be shocked that, without Zoom, she has no school at all.

Jewish stories set in 12th-century China are just a tad less common than those set on the Lower East Side in the early 1900s, but that’s where and when Zhen Yu and the Snake is set. Erica Lyons (author of Counting on Naamah, mentioned above) retells a Talmudic tale about Rabbi Akiva and his daughter but changes the setting, to excellent effect. A fortune teller predicts that Zhen Yu will be bitten by a snake and die on her wedding day. When Zhen Yu performs the mitzvah of giving to the poor, she inadvertently kills the snake and saves her own life. Renia Metallinou’s saturated illustrations with plenty of red bring the story to life.

In The Rabbi and His Donkey, Susan Tarcov imagines Maimonides’ daily trip to the Egyptian palace where he worked as the sultan’s doctor. When Maimonides switches from traveling by donkey to traveling by horse to save time, he discovers that he has more time to write, but less time to think! And without thinking, he has nothing to write. Diana Renjina’s beautiful illustrations utilize a palette of mostly reds, oranges, and golds to add drama to the story.

The last picture book on this list is one set in Israel, something I suspect Jewish parents will be looking for more of in the near future. In Barefoot in the Sand, written by Hava Deevon and translated by Gilah Kahn-Hoffman, two immigrants to Israel, one Ashkenazi from Romania, and one Mizrahi from Yemen, meet. They are dressed differently and speak Hebrew with different accents, but happily discover all they have in common: the same prayers, the same songs, the same faith, the same dream to make aliyah. Exuberant illustrations, including small maps, show the men’s journeys and their joy.

From ‘Counting on Naamah: A Mathematical Tale on Noah’s Ark,’ by Erica Lyons, illustrated by Mary Uhles Intergalactic Afikoman

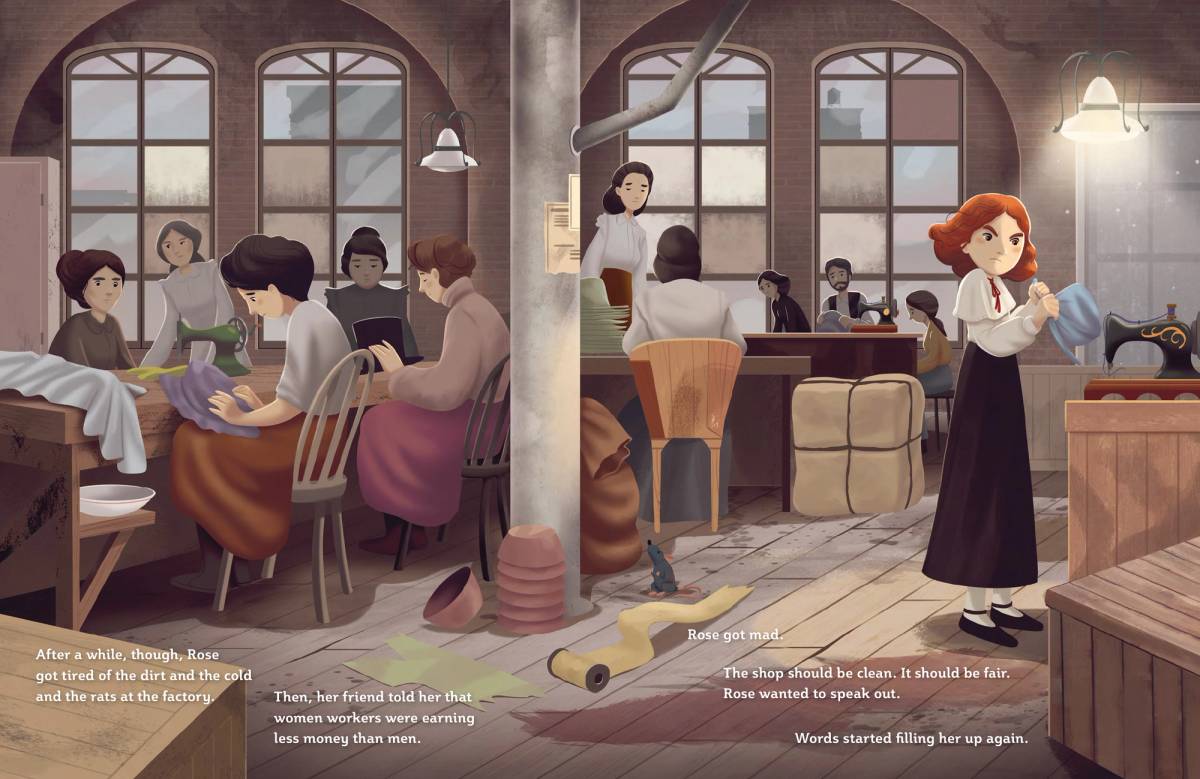

Picture book and graphic biographies, particularly of women, some of whom you are likely to be familiar with and some who will be new to you, are still going strong. This year’s crop includes two compilations, both titled She’s a Mensch! (with different subtitles), as well as books about Rose Schneiderman, Ruth Gruber, Irena Sendler, Debbie Friedman (following on the heels of a picture book bio about her released late last year), and Ruth First. My favorite was Rose Spoke Out: The Story of Rose Schneiderman, a portrait of the labor activist, by Emma Carlson Berne. Illustrator Giovanni Abeille portrays not just Schneiderman’s passion but her anger. Back matter gives more information about Schneiderman’s life and the Jewish tradition of social justice that fueled her activism. Rose Spoke Out could be paired with Brave Girl: Clara and the Shirtwaist Makers Strike of 1909 by Michelle Markel, illustrated by Melissa Sweet, about another Jewish female activist, Clara Lemlich, for a unit on the labor movement and its Jewish female origins.

Even if you haven’t heard of Debbie Friedman, you probably would recognize some of her music, which has had a huge impact on synagogues and summer camps. Debbie’s Song: The Debbie Friedman Story by Ellen Leventhal, illustrated by Natalia Grebtsova, gives a straightforward introduction to Friedman’s life and music with many illustrations featuring musical notes wafting about, and would make an excellent read-aloud for a class learning some of her songs.

While not a biography per se, The Miracle Seed by Martin Lemelman tells the true story of an ancient Judean date palm seed found at Masada and the two women scientists, Elaine Solowey and Sarah Sallon, who coaxed it back to life. Told in a graphic format, the book provides context and history of the Jewish people in the land of Israel including a timeline beginning with the erection of the First Temple in approximately 957 BCE. An epigraph quotes Genesis Rabbah as stating, “There is no plant without an angel in heaven tending it and telling it, ‘Grow!’” Another quote, from C.S. Lewis, says, “Miracles do not, in fact, break the laws of nature.” This is a book for anyone interested in Israel (ancient or modern), botany, or, simply, miracles.

While there were many noteworthy Jewish picture books this year, middle-grade pickings were slimmer. Friendship, relationships with parents, bar/bat mitzvahs and Jewish mysticism remain evergreen topics. Strangely, two of my favorites both reminded me of the movie The Parent Trap (itself based on the book Lisa and Lottie by Erich Kastner, which I loved as a child). Shira & Esther’s Double Dream Debut is author Anna E. Jordan’s middle-grade debut. Set in the fictional town of Idylldale in an unspecified time that seems to be the 1940s, motherless Shira, the rabbi’s daughter, dreams of being an actress, while fatherless Esther, a performer’s daughter, dreams of studying Torah. Hijinks ensue. What makes this book special is not the plot but the voice. It has an old-timey, Yiddishy, folktaley feel that is still enticing to modern readers (“Ah, kinder. It is very hard to make decisions on an empty stomach. I always say eat first, think later.”) and it is not until the last page that we find out for sure who has been narrating the story. A Yiddish glossary at the end is useful, but also funny, in keeping with the tone of the book. (“Tuchus: You’ll excuse the expression—your fanny. The thing you sit on. Your derriere, bum, backside, buttocks, bottom. The thing your parents wiped for years. And don’t you forget it.”)

From ‘Rose Spoke Out: The Story of Rose Schneiderman,’ by Emma Carlson Berne, illustrated by Giovanni Abeille

APPLES & HONEY PRESS

The Jake Show by Joshua S. Levy features only one kid, not two: Jake. So how does it remind me of The Parent Trap? Well, Jake acts like two different people, depending on which of his divorced parents he is with. In fact, he actually goes by different names: With newly religious, remarried mom he’s Yaakov, but with his mostly secular dad and his non-Jewish stepmom, Kayla, he’s Jacob. His parents are constantly playing tug-of-war with him, moving him from religious schools to secular schools and back again. When he switches to a more modern Jewish school and becomes friends with Caleb and Tehila, he decides he must go to the summer camp they are always talking about (another Parent Trap connection). While Jake’s scheme to attend Camp Gershomi (not Jewish enough for his mom, too Jewish for his dad) without either of his parents knowing is a bit far-fetched (and indeed, eventually falls apart), it makes for a fun, suspenseful read. This book stands out by addressing the very common Jewish experience of having family members who have different levels of observance. It also contains an all-too-rare positive portrayal of stepparents, who here have a friendly relationship with each other and exert a moderating influence on their spouses.

In The Witch of Woodland, by Laurel Snyder, Zippy’s love of magic and her parents sudden, unexplained desire for her to have a bat mitzvah intersect in surprising ways. As her former best friend seems to outgrow her, witch-obsessed Zippy struggles socially until she meets a strange, winged, ghostly girl named Miriam. Miriam can’t remember her past, and soon Zippy seems to forget some of her own memories. Who is Miriam, anyway? Is she even real? She’s not a golem or a dybbuk. Is she an ibbur, a supernatural, magical creature who gains strength by depriving its host of hers? Snyder addresses themes of the power of language (and specifically, names), memory, identity, friendship, relationships with parents, and uncertainty with a deft touch. With enough magic to satisfy fantasy lovers and enough friendship and parent drama to satisfy realistic fiction fans, The Witch of Woodland is a winner.

Friendship and parent troubles know no time or place, as we can see from Miriam Halahmy’s A Boy from Baghdad. Although the setting and history will be unfamiliar to many young readers—and their parents—Salman’s struggles with friends and family will be utterly relatable. It is 1951 in Baghdad and the Jews must leave Iraq. Twelve-year-old Salman does not understand why. Iraq is his home. When he and his extended family, some nearly 200 people, are airlifted out of Baghdad as part of Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, things only get worse. Just as European Jews were disappointed to find that American streets were not paved with gold and that they had to live in tenements and work in terrible conditions, so Iraqi Jews were unpleasantly shocked to find themselves living in tents, enduring bugs, heat, and awful Eastern European food (margarine! herring!), being looked down upon by the Ashkenazim, and forbidden to speak their native Arabic. Halahmy brings Baghdad to life with sensory details, especially smells: the odor of the River Tigris, of the “stale, meaty smell” of carcasses at the meat market, and the “heady perfume of cinnamon, cardamom, and chilies” at the spice stalls. Halahmy does not shy away from the difficulties many Mizrahi Jews faced upon arriving in Israel, both socially and economically. But Salman—now Shimon—gradually acclimates to his new home, finding friends both Jewish and Arab. He figures out how to do what he loves, swim, not in the calm Tigris but in the choppy, salty Mediterranean, while gaining the respect of his strict, traditional father. Other characters showcase the many types of immigrants who came to Israel and the paths they pursued, without feeling like caricatures. Salman’s sister, for example, joins a kibbutz and stops keeping Shabbat; Salman and his business-minded cousin Latif meet a Holocaust survivor. Despite their struggles, Halahmy ends the book on a hopeful note. Although A Boy from Baghdad’s uniqueness lies in its setting, its power lies in its universality, and a good novel to read for those who enjoyed Sarah Sassoon’s picture book about Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, Shoham’s Bangle.