Both Sides Now

As the abortion debate heats up, Christian groups in New York—on both sides—stake out positions beyond angry rhetoric and stereotypes

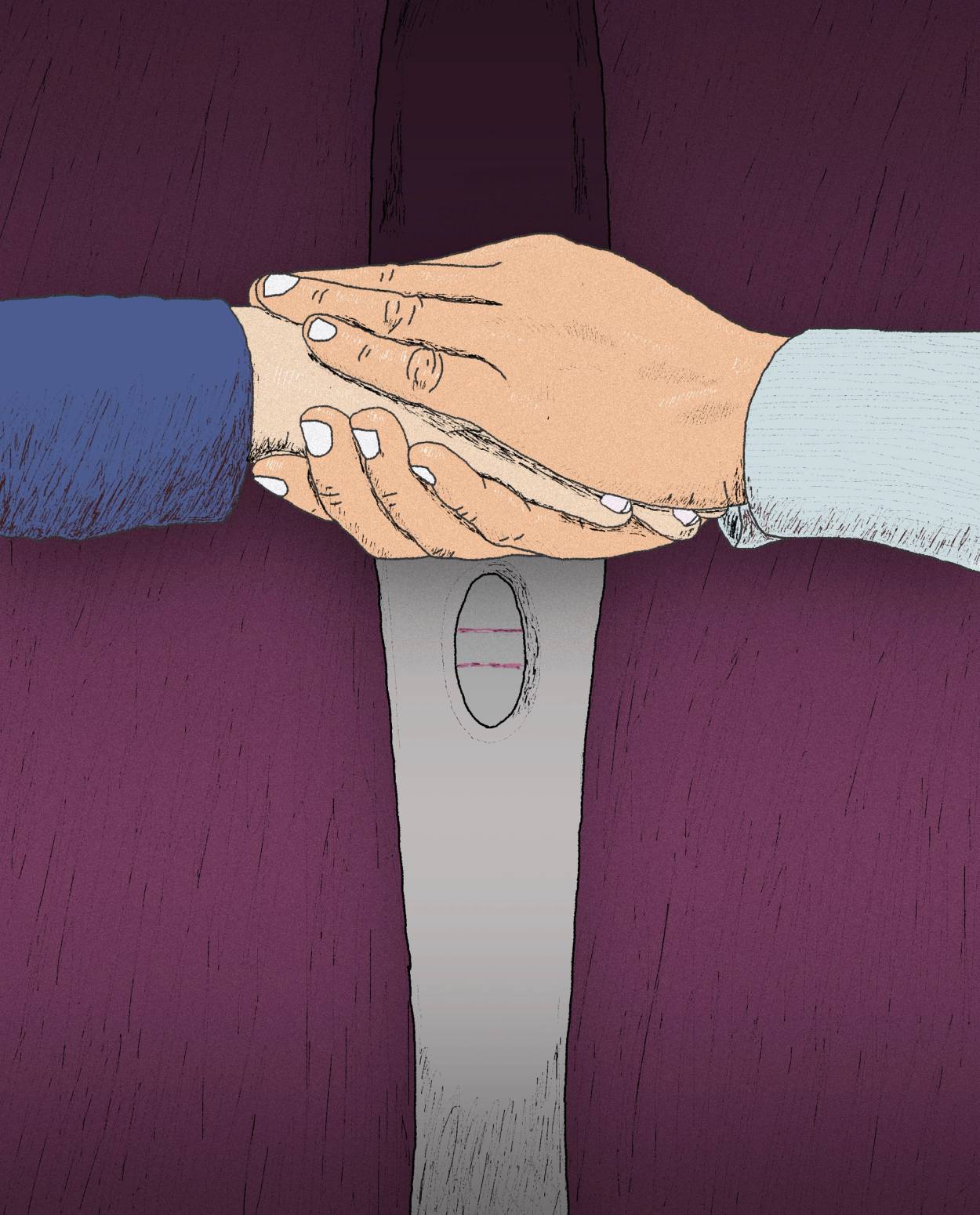

With the abortion debate at a fever pitch since the leak of Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s draft decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, Christian groups in lower Manhattan are responding—on both sides. The Roman Catholic Sisters of Life is helping women keep pregnancies, even in the darkest circumstances, while Judson Memorial, Middle Collegiate, and First Presbyterian Churches advocate for abortion access in addition to a host of progressive social justice causes. Between slogans like “Keep your rosaries off my ovaries” and “Life begins at conception” that appear on signs at rallies and protests, religious perspectives on abortions and the people who have them—nearly two-thirds of whom claim a religious affiliation—are often more nuanced than activist messaging and stereotypes suggest.

The Sisters of Life is a women’s religious order that operates Visitation House, a hub for pregnant women, mothers, and their children, tucked away in the undercroft of St. Andrew Catholic Church. It is located in Foley Square, also known as Federal Plaza, home to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, the Second Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals, and NYPD headquarters. I arrived there less than a week after the site played host to protesters reacting to the leaked Alito draft decision. “Abort SCOTUS” read a bit of graffiti in the square.

Visitation House is one of a handful of Sisters of Life locations, with a staff of 11 sisters on site. It has been at Federal Plaza only around four years, and has a homey, improvised feel: A large white event tent in the middle covers long, set tables, and functions as a dining room, while hinged wooden boards with cloth stapled over them serve as dividers to create receiving rooms and meeting spaces. My guide, a soft-spoken woman called Sister Amata Filia, showed me the church’s old gift shop, now serving as what she called their “mission control” center, an office space with young sisters at work behind computers. There are plans to renovate the old rectory to have more permanent offices and spaces, but it’s been slow going. “We just continue to kind of make it work,” she said.

As is frequently the case when children are involved, what began as improvisatory has somehow become the modus operandi at Visitation House. “We’re always amazed because sometimes we feel a little hesitant about it like, ‘Oh don’t mind the mess,’” said Sister Amata, “But I mean, almost always, the moms come in here and they’re like, ‘Wow, I feel so much peace here, this is so nice.’ Most of them are coming from tiny little apartments or shelters, or just places that they don’t even have room to move around or the kids to play. Hopefully it’s more the relationship they’re receiving, too, they feel at home here even if the externals aren’t perfect.”

Over tea and cookies in one of those small makeshift rooms, Sister Amata explained what happens when a pregnant woman comes to Visitation House. The women usually phone ahead to schedule an appointment—Visitation House is open Monday through Thursday, with Fridays and Sundays being reserved as days of prayer for the sisters. Women find out about the Sisters of Life from social workers, priests, friends, or somebody in their building who has previously been helped by the sisters. “It’s a lot of word of mouth,” said Sister Amata. “Sometimes they’re even someone going into say, Planned Parenthood for their abortion appointment, and they’ll speak to somebody who’s praying outside who gives them a brochure and says, this is another option for you, and they’ll come over and see us [and] explore other possibilities.”

When I asked how often this last scenario occurs, Sister Amata said, “More than you would expect. Several each week. Especially in recent years, I think, because I think the presence out in front of the clinics has gotten greater and more steady, and I feel like there’s a lot of good resources out there now to train sidewalk counselors to perhaps do outreach in a way that will actually reach women and not just push them away further, when it’s done in a prayerful spirit.”

Sidewalk counselors differ from the agitating protesters known for carrying upsetting photos of mutilated fetuses or yelling fire-and-brimstone warnings at women. They aren’t necessarily the ones outside with rosaries (or inside), either. The women who come to Visitation House are often referred by trained volunteers from Sidewalk Advocates for Life, a national, cross-denominational Christian organization providing training for what they call sidewalk advocacy, which they say is intended to emphasize “the peaceful, prayerful, law-abiding methods of this ministry with love as its centerpiece.” A Sidewalk Advocates for Life-trained sidewalk counselor with whom I spoke said counselors can take a range of approaches to speaking to women approaching the clinic, from holding signs to approaching the women (New York state prohibits obstructing access, causing damage, or issuing threats outside of clinics, but does not require buffer zones).

Those points of contact can take the form of a phone call from the clinic with a woman, when Sister Amata said the woman will talk to the sisters for a few minutes. Sometimes these women will actually come to Visitation House in person. When it comes to how many women choose to keep their pregnancies, Sister Amata said, “Probably half the time. Especially if they can come in.” The aim, she said, is to “get them to the point where they’re open to at least just coming for a visit to hear us out.” She said the women don’t have to be Catholic, nor are they expected to become so. “Faith is never something that we push on anyone,” Sister Amata said. “We serve anyone of all backgrounds, all faiths, socioeconomic backgrounds, cultures.” And they get them. “We really do see a lot of everything. From the Upper East Side married couple who has it all, but received an adverse prenatal diagnosis, and they’re being pushed by the doctors to have an abortion.” (For these types of situations, Sister Amata mentioned a neonatal hospice program at New York Presbyterian.)

Initial visits can take hours, according to Sister Amata. “We’ll just sit down with them, kind of like this,” she said, gesturing to the tea tray between us, “have, like, a tea party, basically.” Then, said Sister Amata, “We’ll just listen to them, hear their story, what are they experiencing, what is the situation, what are their fears, what are the pressures maybe that they’re experiencing. But beyond that, what are their dreams? Their goals for life? Because this new life given to them doesn’t necessarily have to be the end of all of that. So we kind of just try to receive them where they are, and just hear what’s going to be helpful for you, and also help them kind of almost discover it for themselves, like, well, what is your heart saying about this? Because more often than not, they want to choose life, they just feel so overwhelmed by the circumstances, or it just doesn’t seem possible, or the people who ought to be supporting them aren’t, and so we just try to gently fill in maybe the gaps for that, and you know, offer referrals to other places. But also a promise to continue to walk with them for as much as it’s helpful for them.”

After the baby’s born, we’re not just going to be like, ‘See you, goodbye, we’re done with you!’

The focus isn’t on the fetus. “We rarely, especially at the very beginning, talk about the baby directly,” said Sister Amata. “Our main focus is actually on the mother and on helping her see her own goodness, her own dignity, her own strength, because if she believes in herself, she’s going to be a good mother to this child, she’s going to have the faith it takes and the courage it takes to do whatever it takes to welcome this life into the world. But it’s when she feels alone abandoned, you know, unworthy, that’s when she’s more likely to despair.”

Statistics from the pro-choice Guttmacher Institute support Sister Amata’s claims about the women’s concerns. Abortion patients disproportionately tend be poor or low-income, and among the primary reasons U.S. women gave for obtaining abortions between 2004 and 2010 were not being financially prepared, and not being the right time for a baby.

A legion of volunteers, whom they call coworkers, enable the Sisters of Life to offer women more than a listening ear. Sister Amata said the sisters can connect women with these volunteers for a variety of things. She cites assistance ranging from professional services and help with resumes, to picking up and dropping off car seats (there were several in one of Visitation House’s four well-stocked store rooms), throwing baby showers, or even meeting for coffee and conversation once a week. I saw about four volunteers, when I was there on a weekday afternoon: lay people, Black and white, women and one man, sorting and organizing.

Like the sidewalk counselors, coworkers are trained. Their program includes modules on reflective listening and understanding the perspective of a pregnant woman. Recently, the Sisters of Life, in partnership with the University of Notre Dame, released Into Life, an adapted online version of their coworker training, intended to encourage productive conversations both with and about people who seek abortions.

The Sisters of Life have what Sister Amata called “a principle of nonabandonment.” “After the baby’s born,” she said, “we’re not just going to be like, ‘See you, goodbye, we’re done with you!’” Sister Amata said while they can’t give direct financial assistance, they can provide families with gift cards along with items from their Visitation House storerooms. (“Don’t go buy the diapers, we’ll provide that, and you use that money for your rent, you know what I mean?”) In unique situations, she said they’ll do “a direct ask” among their volunteers. “We’ve had coworkers donate their frequent flyer miles so we could move a mother out of New York to a maternity home in a different place,” she said. Sister Amata estimates of the thousands of people on their email list, there are about 1,000 active volunteers in the tristate area, not all uniformly pro-life or even Catholic.

Throughout my visit, the sounds of women’s voices were ambient, speaking both English and Spanish. I saw two young women draped over chairs, chatting quietly with iced coffee in hand, and a sister in the order’s signature blue and white habit leaving an occupied meeting room with finished plates of food. I overheard a sister recommending to a mother a parenting book which I had meant to ask Sister Amata whether she was familiar during our interview. As I left, a young child’s voice resonating from somewhere in the building, I walked past a stocked changing table, and an empty stroller parked by the door.

That same week, I met with Greg Stovell, senior pastor at the 304-year-old First Presbyterian Church of New York City. Like the other Manhattan pastors I interviewed, he was eager to share with me his church’s place in American history. “Rebels since the beginning,” he said, the church was the preferred place of worship for patriots during the Revolution. He also showed me the font where Theodore Roosevelt was baptized as an infant.

First Presbyterian’s ornate, wood-carved interior and stained-glass windows evoke a traditional Scottish kirk, while the reception area where I met Stovell was bright and polished, with an airy modern interior. It’s an apt metaphor for Stovell’s description of his congregation: “Very traditional service, but incredibly progressive.” He said the congregation is “not just blue,” but “electric blue.”

First Presbyterian belongs to Presbyterian Church USA (PCUSA) branch, one of the largest branches of Presbyterianism in America, with a more theologically liberal orientation. Even still, Stovell said, “PCUSA is a really big tent. We can just go across the river and the church will be 100% different from this one.” He characterizes the overall persuasion of PCUSA (“if we’re going to do labels”) as moderate or centrist right, “all the way to way left.” This, Stovell said, makes a one-size-fits-all doctrinal stance on abortion a complicated prospect that can vary by congregation or pastor. He said while PCUSA congregations have tended to be pro-choice, congregations out near Dallas or Houston, for example, “tend to be more pro-life.”

Stovell said his particular congregation at First Presbyterian hosts a variety of initiatives: groups for artists, Bible studies, and an online current events group that started to keep up with the candidates in the run-up to the 2020 elections, “modeling how Christians can speak in a civilized way on politics,” that now looks at things like local and national elections.

They don’t just talk about events, however. Since he came on board about a year and a half ago, Stovell said advocacy work takes the form of letter writing, women’s marches (“most of the sanctioned, well-organized ones,” he specified), and a weekly soup kitchen, in cooperation with nearby St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. Other initiatives include work with mission partners for things like coat drives, immigrant and refugee ministry, and LGBTQ rights work. Stovell said prior to his time there, pastors have served as liaisons to Planned Parenthood, he thinks primarily in a counseling capacity. “Our main ministry when it comes to reproductive rights right now has to do with pastoral care,” he said.

Stovell described meeting with women either before or after their procedures, usually after, and often as many as 10 or 15 years later. Stovell said the women usually reach out to the church directly, a fact he attributes to its Fifth Avenue location and proximity to college campuses. Nor are they exclusively church members. “Everybody’s different,” said Stovell. “In some cases it’s an assurance that it is their choice, and others, it’s just pastoral care, it’s just listening, praying with them. In very few cases they have questions about what the Bible has to say. But in most of those cases, they don’t really want to know exactly what the Bible has to say, they want to know how to strengthen their faith as they’re going through the sometimes effects, sometimes trauma, sometimes processing decisions.”

In this way, his approach is not so different from Sister Amata’s. “Oh, no,” said Sister Amata when I asked if her order did any kind of legislative advocacy around life issues. “I mean we’re following that out of interest,” she said of the Supreme Court leak. “Obviously, it affects everything, but no, the legislative stuff, we pray for it,” she said with a laugh, “But we’re much more of a heart-to-heart, person-to-person focus for sure.”

Judson Memorial and Middle Collegiate Churches, both in Greenwich Village, emphasize activism in addition to personal connection when it comes to abortion. Both are affiliated with the United Church of Christ (UCC), a mainline Protestant denomination descended in part from the early Puritans of New England. UCC has a history of supporting reproductive choice for women going back to the 1960s as part of the Clergy Consultation Services on Abortion (CCS), a pre-Roe network of interdenominational faith leaders dedicated to legalizing abortion.

Abigail Hastings at Judson Memorial Church, located in the heart of the NYU campus, is a Baptist pastor associated with the progressive Alliance of Baptists and the church’s archivist. (Judson is bi-denominational, with a congregation that combines membership from American Baptist Churches USA and the UCC.) Judson was a key part of the creation of the CCS, Hastings said.

She said in Judson’s DNA is “having a heart for the needs of the people, just go and listen to what is it that people need.” According to Hastings, this focus is the reason that Judson pastors in the 1950s noticed the need in Greenwich Village for more space for artists, the genesis of Judson’s well-known performance space that is open to secular artists of all kinds. She attributes the church’s freewheeling character, which runs contrary to the popular image of Baptists as nondancing teetotalers, to a Baptist principle known as soul freedom, or soul competency—the belief that there is no mediator between the believer and God.

The CCS came about through the cooperation of Judson pastor Howard Moody, who stepped down in 1992 after 35 years in the position. “For us to get involved in the abortion issue is not so surprising because you know, Howard would look around and say, ‘We need what?’” Hastings said. The issue came to Moody’s doorstep “literally,” according to Hastings, when a former Judson pastor referred a young woman in search of an abortion to the church for counseling in 1957. The difficult, emotional experience of trying to help the woman procure an abortion, which was illegal at the time, opened Moody’s eyes to the reality of the issue. Less than a decade later, an interfaith discussion group of clergy Moody had been meeting with decided to form a coalition to help women access safe abortions, as well as to lobby for legislative reform. Judson Memorial Church housed the call center for the CCS’s work of referring, aiding, and advising women seeking abortions, as well as assisting those women who desired to keep their pregnancies. In 1969, there were even confidential plans for an abortion clinic, which they called a Reproduction Crisis Facility, in the church house behind Judson’s site on Washington Square. CCS was more than a New York phenomenon, however. By 1970, CCS had known chapters in 26 states.

“Howard used to say the church exists for the world,” said Hastings, “And that orientation means that you’re constantly saying where can we give help? Being in the Village, we’re bohemian and maybe freer thinkers, but it means we were able to take on issues that other churches could not or would not want to touch.”

After Roe v. Wade, Hastings said many CCS chapters, including the one in New York, converted to women’s health centers. Judson is not nor has it been a very large church historically, according to Hastings, who estimates current membership at around 200. She describes the church’s motto as “light a torch and pass it on.” She sees Judson’s role as keeping its ear to the ground, identifying needs in the community, getting initiatives started, and then “ideally, handing it off to the people who are affected.”

When a pregnant person decides that they need an abortion, they are making a choice because they are created in the image of God with agency.

Today, Hastings said the emphasis at Judson has shifted from reproductive rights to the concept of reproductive justice. In her estimation, the passage of the Hyde Amendment, which restricts public funding for abortion, effectively ended abortion access for many lower-income women, which together with a lack of access to high quality prenatal care, she contends is responsible for the higher maternal and infant mortality rates among people of color (maternal death rates for Black women are particularly high). Judson briefly had a website, the Empathy Project, which was envisioned as what Hastings called “CCS 2.0.” However, staffing problems proved difficult, and today, Hastings said CCS’s legacy survives in faith-based reproductive justice groups like SACReD and the Religious Coalition for Reproductive Choice, which offers, among other services, blessings of abortion clinics. She said while Judson is considering how to continue to be active in the field, she said the recent resignation of their pastor of 15 years has kicked off a period of transition and what she calls “internal work” at Judson. “But we’re out there in the marches with our banners,” Hastings said. “And we’re looking for opportunities.”

A 2019 post on Judson’s Instagram account shows the church participating in Stop the Bans Day of Action, an advocacy event held by NARAL and other high profile pro-choice organizations in response to Alabama’s ban on abortions, except in the case of risk to a woman’s life or a life-threatening fetal abnormality. “Thank God for Abortion,” reads a banner hanging from the church. Below the words, a drawing of a dove hovering over outstretched hands. That same day, Senior Minister, Rev. Donna Schaper, appeared in a separate post at a Planned Parenthood rally in Washington, D.C., in front of the Supreme Court. “I stand with Planned Parenthood” reads her pink fan.

For Moody and his colleague, CCS staffer Arlene Carmen, Hastings said, “It didn’t really matter what the issue was, if they could do direct service, they would, but more importantly, they were always looking at public policy, they were always looking at, how can you change the laws, so that we’re not doing this kind of Band-Aid ministry, but can really make effective change for the largest number of people, which needs to be done through legislation.” It’s a worldview that persists at Judson, Hastings said. “Any one issue has a lot of tentacles and things to explore.”

Jacqueline Lewis, senior minister at Middle Collegiate Church, is a Presbyterian-ordained minister whose congregation is affiliated with the Reformed Church of America, which has its roots in early Dutch settlers to North America. About 20 years ago, Middle Collegiate also aligned itself with the UCC. “Faith means justice,” she said. “As a child, I learned that faith meant mercy. As a child, I learned that faith meant God will always love you.” Lewis said that for her, this translates into putting compassion first, “opening doors to people to get what they need.” As a result, she said, “when a pregnant person decides that they need an abortion, they are making a choice because they are created in the image of God with agency.”

Like Sister Amata and Greg Stovell, Lewis has counseled women about abortion, both before and after. Women who are victims of rape or incest, or women “who just cannot have a baby right now,” she said. “Just can’t do it, don’t want to do it.” Lewis speaks of a “growing understanding” of the reasons why women get abortions: “We support a person’s right to make autonomic decisions for their own life and their own circumstances,” which she calls “an act of faith in God.”

Middle Collegiate is, she said, the oldest continuous Protestant church in North America, dating back to 1628. Today, its building is surrounded by fencing and construction work as the members rebuild from a fire in December 2020. As they work to repair their building, she said they are also working to repair their church’s historical complicity in taking the island of Manhattan from the Lenape tribe, and the city’s debt to the labor of enslaved people. Lewis said these reparations have taken the form of food pantries, clothing drives, after-school programs, of responding to the needs of victims and families during the AIDS crisis in the East Village, centering anti-racism in their work, support for LGBTQ rights, and most recently, assisting Ukrainian refugees. Lewis includes the church’s efforts to uphold Roe in recent years in these restorative efforts. “In these last few years when we have felt the threat against Roe v. Wade,” she said, “we stood against the justices who were against the women.”

On May 9, the church’s Instagram account posted attendee information for “Leaked SCOTUS Draft: A Space for Processing and Action,” hosted by Lewis and other Middle Church clergy. Members were invited to join them “to process the recent leaked SCOTUS draft and how together we can act toward justice and care for one another well.” Planned small group discussions were centered around worries, triggers, and information-sharing about actions being taken in response. “Come, share with family, and let’s talk together about how we’re going to keep each other safe.” A couple days later, followers were invited to join them at noon on May 14 at Cadman Plaza in Brooklyn. “Say it loud,” the caption read, “The majority of the U.S. supports abortion rights!” From there, they would march across the Brooklyn Bridge to the large protest at Foley Square, where the Sisters of Life and the courts share a front yard

“Our justice is activism,” said Lewis of Middle Collegiate. “But it’s also tikkun olam. How do we really work to repair the world? In our congregational life, in our families, in our writing, speaking?” In response to recent abortion controversies, Lewis said, “We’ve been on the steps of the Supreme Court, walking across the Brooklyn Bridge, we’ve been in all of these protests for the last two months, we’ve joined with our colleagues to write letters, we’ve been in the Zoom room speaking with activists across faiths, so we’re continuing to pressure.” The next step, Lewis said, is preparing to bring women to New York who need access to abortion: housing them, helping them financially, “to make a tabernacle for people who need to come,” in the same way congregation members have been able to make sanctuary for Ukrainian refugees and immigrants.

COVID-19, followed by the fire, have had a surprising effect on Middle Collegiate, which currently holds services at the East End Temple. Lewis estimates their membership numbers have grown from about 1,300 to around 1,900 members globally since March 2020, as people tuned into broadcasted services. “People are looking very much to operationalize what they think is fierce love in action,” she said. While Lewis said they are looking to open branches in California and as far as Malawi, “we’re deeply local still. We still feed people. We’re still making grants to people who need help because of COVID, we just made a grant to someone to help her pay her mortgage.” They continue to donate to racial justice programs and activists.

Today’s siloed media environment frequently prohibits the type of nuance and subtlety that a topic like abortion demands. Hence, people who believe themselves to be peaceful “Witnesses for Life” become the other side’s “anti-choice fanatics,” and people of goodwill who believe in abortion access become the “pro-death” side against which you must prepare your children. The Sisters of Life, however, are not merely pro-birth any more than the pro-choice Christians at Judson, First Presbyterian, or Middle Collegiate see themselves as enemies of a gospel message that obliges them to care and advocate for the most vulnerable.

The range of approaches to abortion in Lower Manhattan alone—from legislative activism, to support for pregnant women, from addressing broader community quality of life issues, to improving abortion access—reflect the broader opinions of Americans in general around the issue. As many as 90% may oppose overturning Roe, but with regard to specifics (60% support for first trimester abortions drops by over half for second trimester procedures), the nation appears more conflicted. Life is hard and people are complicated, facts that are often overlooked in a heated national debate centered explicitly around both. But beyond the noise and behind the scenes are people of faith, hard at work in the name of compassion.

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.