Changing Life Behind Bars

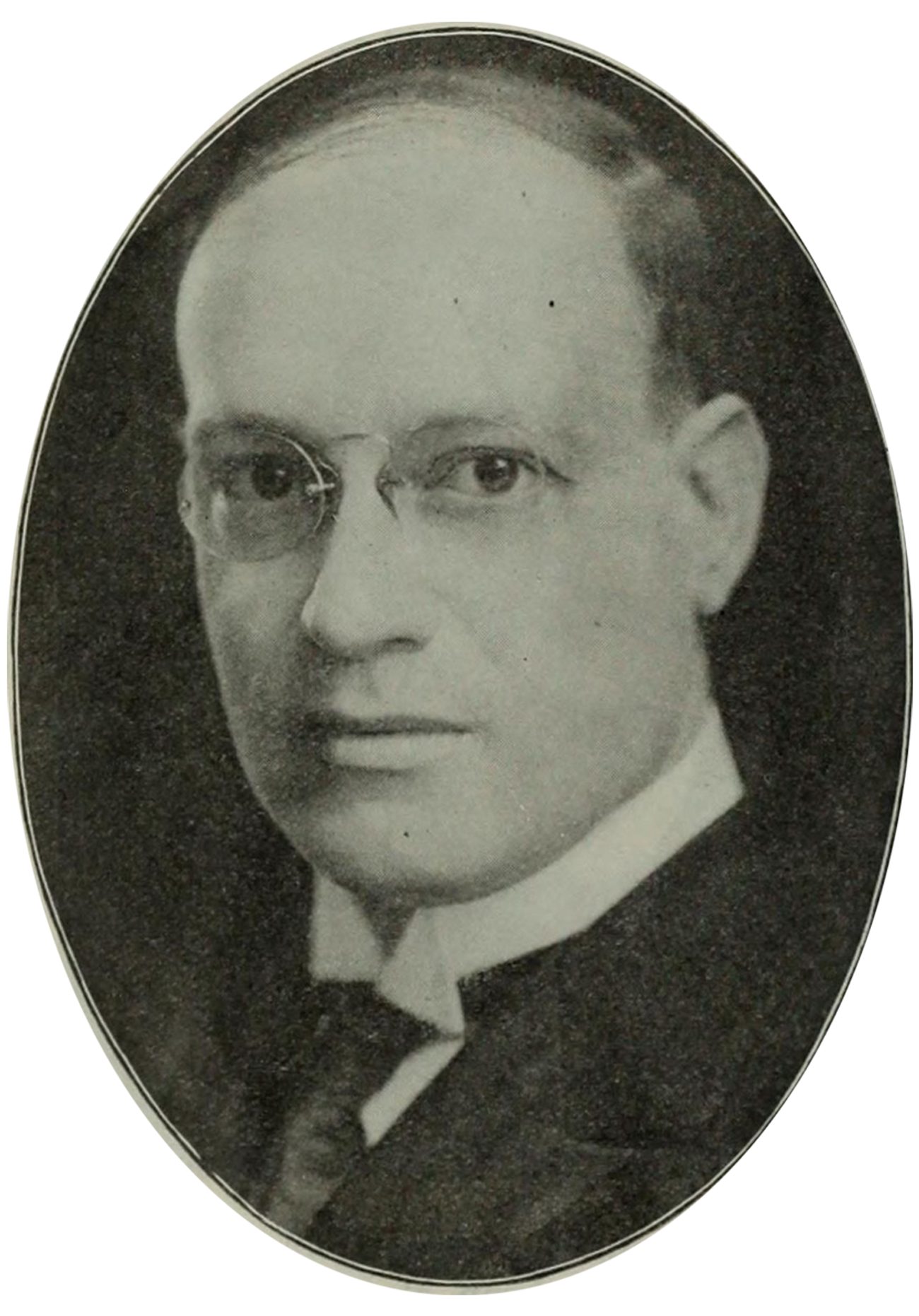

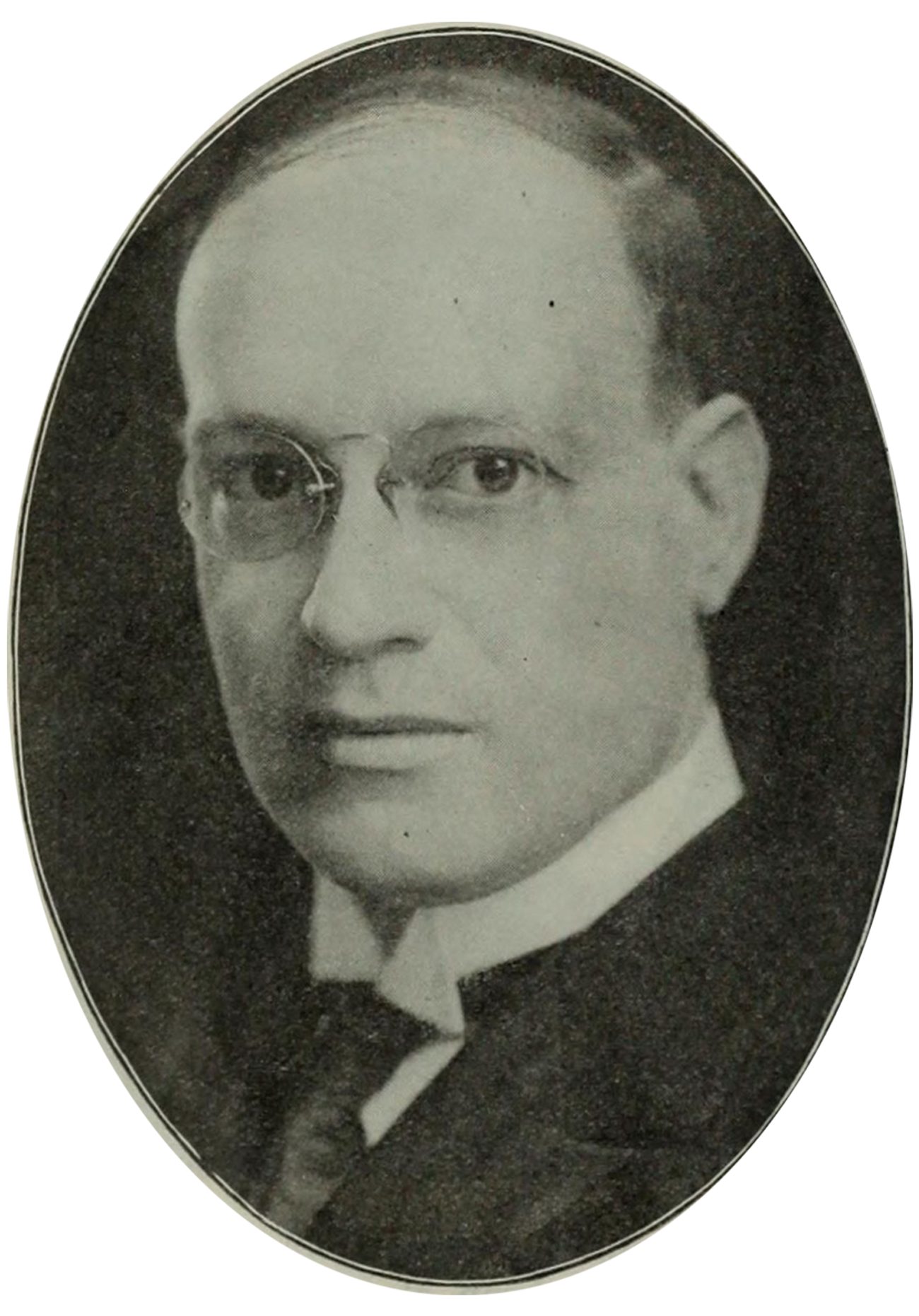

As a chaplain and advocate for reform, Rabbi Rudolph Coffee brought Jewish services and kosher food to California prisons in the early 20th century

“Prisons nowadays still don’t know how to deal with Jewish issues,” said Matthew Perry, a chaplain and executive director for Jewish Prisoner Services International and the Jewish representative to the American Correctional Chaplains Association’s executive board. For instance, kosher food, or the lack thereof, is an ongoing concern for Jewish inmates.

In February, a federal judge hinted that Russell Boles—an Orthodox Jew being held at Sterling Correctional Facility—may have a legitimate claim of religious discrimination against the Colorado Dept. of Corrections. Boles said his meals (which he called “swine slop”) were not acceptable under Jewish law. Last year, Jewish inmates in Arizona sued their Department of Corrections over a change in their kosher meal program, and Jewish inmates in Michigan won the right to kosher meals on Jewish holidays, including cheesecake for Shavuot.

But such complaints and lawsuits are indicative of important progress: Jewish inmates today do typically have access to kosher food—as well as services and celebrations with community volunteers—since the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed religious rights for prisoners in 2005. But this was not always the case. A few jails offered kosher food or Jewish services as far back as the 1850s, according to an article written by chaplain Gary Friedman, JPSI’s founder. But decades later, little progress had been made; a century ago, only a handful of prisons offered such things.

One pioneering Jewish chaplain, Rabbi Rudolph Coffee, changed all that. Coffee was ahead of his time in ushering in services for Jewish prisoners in the early 20th century at some of the country’s best-known prisons: San Quentin and Folsom state prisons in California, as well as Alcatraz, the maximum security federal prison on an island in San Francisco Bay.

“He opened the road for religious observances at these prisons in California at a time when all people really knew about was Christianity,” said Perry. “It’s very impressive.”

Coffee was born in 1878 in Oakland, California. After graduating with a bachelor’s degree from Columbia University in 1900, he was ordained as a rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York—part of the Conservative Jewish movement—even though he was later affiliated with the Reform movement’s Central Conference of American Rabbis. After he was ordained, Coffee attended graduate school and received his doctorate from the University of Pittsburgh in 1908.

Coffee was an ardent activist, championing prison reform and rallying for a host of progressive causes. He supported disarmament, birth control, and higher salaries for government employees. He was against the death penalty, Prohibition, and war. He also condemned antisemitism. Coffee’s career is peppered with charitable positions. From 1900-03, he was the religious director of the New York City YMCA. He was also the superintendent of New York’s Hebrew Orphan Asylum and was later appointed director of the Social Service Department of B’nai B’rith in Washington, D.C., in 1915.

After serving as rabbi for several synagogues, Coffee accepted a position at Oakland’s Temple Sinai (his relatives were some of the synagogue’s earliest members) from 1921-33. At a time when it was uncommon for rabbis to preach social justice causes from the pulpit, Coffee—whom the temple refers to as a “powerful speaker”—made it his mission to bring awareness to the issues of the time.

“Coffee was actively engaged in social causes. The synagogue is not usually a place for this,” said Fred Isaac, an East Bay community historian. “He was on the side of reform and propriety; he was a leader in this way.”

Other than preaching from Temple Sinai’s bimah, Coffee also wrote articles and letters for different publications, including the Jewish News of Northern California and New York Times. In a 1924 New York Times letter to the editor, Coffee wrote about reform at women’s prisons. He stated that “my limited study convinces me that women prisoners are worse off than men.” The state Board of Charities and Correction—of which Coffee was a member—was successful in getting a manual training teacher to help women earn money while in prison. As president of the Jewish Committee for Personal Service, he also arranged for rabbis to act as “big brothers” to help Jewish inmates adjust to life after their release.

His passion for prison reform led Coffee to volunteer at San Quentin and Folsom in 1921. In 1925, he became the first appointed Jewish chaplain of the California Assembly. He was also the first rabbi elected president of the National Chaplains Association (now the ACCA).

In 1934, Coffee was tapped to be the chaplain at Alcatraz. He held High Holidays and Passover services and meals at all three prisons. According to Dutch researcher A.G. Sevinga, Alcatraz’s then-warden James Johnston said, “[Coffee] has served us well by administering to the welfare of the Jewish inmates. Dr. Coffee has regularly arranged for services for the Jewish inmates on their Holy Days and has visited and counseled with them at other times as requested or as seemed to him advisable.”

Coffee and several inmates presided over a Passover Seder at Folsom, which included a meal of matzo balls, salami, and salmon. He and prison officials talked to the inmates about what it meant to them to be Jewish, according to Perry. These meaningful holiday observances for Jewish inmates led to Coffee conducting High Holiday services at all of California’s state correctional institutions in 1942. That same year, he was employed in an official capacity as chaplain at San Quentin and Folsom.

His changes went beyond straightforward religious observance. In 1947, he wrote a request in the Jewish News for books and a typewriter for San Quentin inmates: “Here are two requests which will be of great help in strengthening the morale of our Jewish group.”

Coffee brought services and kosher food into prisons when it was extremely uncommon. While it’s unknown how far-ranging access to kosher food was across the country during Coffee’s time, Perry believes Coffee was influential in bringing services to Jewish inmates on a national scale. “There are now services at all the CDCR facilities and before [Coffee] there were none,” he said.

Coffee did have detractors. In Fred Rosenbaum’s book Free to Choose: The Making of a Jewish Community in the American West, Coffee was described as “the epitome of a do-gooder,” but others believe Coffee may have only acted out of self-interest. Alcatraz inmate Morton Sobell wrote in his book On Doing Time that Coffee only talked about himself and his wife during one Passover service and didn’t ask the inmates any questions. “On leaving the services, we were each given a couple of pounds of matzos. That was it for Passover,” Sobell wrote. “From other inmates I learned that this was a standard performance for Coffee. … I don’t think he could have been much of a human being even when he first started. Human beings do not turn into cold-blooded bastards …”

While Sevinga said he can’t offer a personal opinion, he said, “Why would [Sobell] lie or write anything false about him? What I’ve noticed is that many chaplains, both Catholic and Presbyterian, sometimes ‘sold’ their activities in their reports trying to paint a positive picture” about themselves.

Coffee was also a charter member of the Human Betterment Foundation, an American movement whose ideas about eugenics echoed Adolf Hitler’s ideas of racial superiority. The foundation supported forced sterilizations for the “less suitable,” which included classifications of “idiocy” and “hereditary degeneracy.”

Despite this controversial stance, Coffee had a mostly positive impact on the community. In 1955, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors honored his 50th year as a rabbi, writing in the Jewish News that with “boundless patience and perseverance he has labored over the years, pouring out his love, his energy and his understanding in unending manifestation of his devotion to Almighty God and to his fellow man … [we] express to Dr. Coffee, the respect and love of a grateful community for unrivalled humanitarian service.”

Coffee continued his activism and employment at San Quentin, Folsom, and Alcatraz until he died in 1955 at age 76.

Perry said his legacy of championing Jewish rights in prisons is inspirational: “He basically said, ‘You’re Jewish, so what needs to be done so that you can practice?’ And this is a hundred years ago, give or take. It’s totally amazing to me.”

Rachel R. Román is a writer and photographer who has written for Forward magazine and Geekwire.com. She has written and taken pictures for the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, The Cholent and Jewish in Seattle magazine.