Children’s Holocaust Literature That’s Worth Reading

The best releases from the past year. Hint: There are no picture books on this list.

As I’ve written before, an outsize percentage of Jewish children’s literature is devoted to the Holocaust. That’s because the Holocaust has an outsize role in Jewish identity. In a 2013 Pew Research Center poll, American Jews were asked, “What does it mean to be Jewish?” The number one answer, given by 73% of respondents, was “remembering the Holocaust.” (“Leading an ethical/moral life” came in second, at 69%; “working for justice/equality” came in third, at 56%. Let that sit a moment.)

Publishers churn out Holocaust books because Holocaust books sell. And because writers, Jewish and not, write a ton of Holocaust books for those publishers to choose from. And because Holocaust books are deemed “important.” So, in an endless cycle of horror and sorrow and loss, we get a glut of Holocaust books for kids.

And bonus! Despite everyone’s best intentions, Holocaust books for kids—and for young adults—are frequently crappy. They soft-pedal how nightmarish the Holocaust was. They fail to put it in political context. They use it as a cheat, a prefab high-stakes setting that provides emotion and drama without the author having to do the work of world-building. They trivialize it by using it as a jumping-off point for unrealistic friendship stories, love stories, and revenge fantasies. (The actual Mengele was bad enough that we don’t have to add creating Jewish teen shapeshifters to his sins.) Too often they feature upbeat endings and reunited families, a disservice to the truth and to the dead, giving the misimpression that more Jews survived than actually did. Too many focus on noble non-Jews rescuing helpless, nearly faceless Jews; books like these often reduce Jews to devices for the education and humanization of the central, more nuanced non-Jewish characters, and turning those who should be centered in the narrative into second-class literary figures without agency. Frequently developmentally inappropriate, these books can trigger huge feelings that small children aren’t yet ready to handle.

And, of course, these books tell (and re-tell and re-tell and re-tell) the story of Anne Frank. This is an insult to a young woman who wanted desperately to be a writer. Frank crafted, edited, and rewrote her own work and yearned for it to be published. Referring to her as a “diarist” diminishes her accomplishment; keeping a diary usually means writing only for oneself, generally with more emotion than skill. The real Anne Frank had huge literary ambition and did the work. She’s earned the right to tell her own story. Yet we preempt her, reworking and editing her words and experiences for audiences not yet old enough for the genuine article. In 2020 alone there were five new kids’ books about her. (There were also three about Ruth Bader Ginsburg and eight about Albert Einstein, thus completing the Holy Trinity of Jewish kidlit biography.)

Ironically, Jewish book publishers produce fewer Holocaust books than their secular counterparts do. Orthodox publishers like Menucha, Feldheim, and Hachai, and nondenominational Jewish publishers like Kar-Ben and Apples & Honey are all extremely selective about publishing Holocaust kidlit. For instance, only two of Feldheim’s 332 children’s titles are about the Holocaust … and neither one is a picture book. PJ Library, which distributes Jewish children’s books for free to kids ages 0-8 all over the world, warns authors and would-be authors: “Due to the age of its participants, PJ Library does not send out books that deal with the Holocaust.” In an email interview, Joni Sussman, the publisher of Kar-Ben, told me, “As a Holocaust educator and a child of Holocaust survivors, I think it’s important for children to be introduced to this topic in a sensitive and age-appropriate way, but even so, Kar-Ben publishes very few Holocaust stories and those mostly based on true events. The Holocaust is only one piece of the wondrous story of the Jewish people, not the crux of who we are. It’s important for our kids to be taught that, first and foremost, the Jewish people live our lives joyously.”

Indeed. Secular publishers need to tell a much wider variety of stories about Jewishness—fantasy, sci-fi, mysteries, stories grounded in Sephardic history, stories about Jews of Color, retellings of biblical stories and midrashim, biographies of unheralded Jewish heroes of other eras, cultures and countries; contemporary stories that address the complexities of life as an acculturated Jewish kid in a multicultural world.

To be fair, mainstream publishers are getting better at including Jews in the very welcome diversity movement. But there’s still a way to go.

And I’m not saying we don’t need Holocaust books. Children must learn this tragic history. Especially now, what with the rioters at the Capitol wearing Camp Auschwitz and 6MWE (6 Million Wasn’t Enough) sweatshirts and tees, with right-wing extremist violence against Jews on the rise, and with American millennials and Gen Zers showing a dismaying lack of knowledge about the Holocaust. (One survey found that 63% didn’t know how many Jews were murdered; 36% believed fewer than 2 million Jews died; 48% couldn’t name a concentration camp or ghetto; and 11% believed Jews caused the Holocaust.) I’m ambivalent about Holocaust books as entertainment—if you want to buy your kid a book to read for fun, check out my list of the best Jewish children’s books published in 2020—but Holocaust books are essential for our kids’ education … and our country’s.

The best Holocaust books for kids published in 2020 are:

Peter’s War by Deborah Durland DeSaix and Karen Gray Ruelle. Short, unflashily written, and rigorously researched, it’s the true story of Peter Feigl, a 12-year-old Jewish boy whose family fled Germany for Czechoslovakia, then Austria, Belgium, and France, where his parents were finally captured. From 1942 to ’44 Peter was on his own, living in a series of homes and schools and even working with the Maquis, the French Resistance. Peter’s War offers tons of historical and personal photos as well as gentle watercolor paintings, plus images from Peter’s actual childhood journal. The detailed back matter offers sources, notes, and a bibliography. It’s responsibly done (Peter’s parents do not survive, which is a common truth we need to tell) without being either too terrifying or boring. (Ages 8-11)

We Had to be Brave by Deborah Hopkinson. This is an astounding feat of research and an invaluable resource for future generations. It’s the story of the Kindertransport, told largely through the experiences of three real children—a boy named Leslie and two girls named Marianne and Ruth. We learn about their privileged, regular-kid prewar lives, full of games and toys and schoolwork, and then see how Hitler’s plans began to encroach on their world. The book weaves together their stories with straightforward narration about Kristallnacht and how the Kindertransport came together, plus snippets of first-person interviews with many other children, rescuers, and historians. The rich back matter provides a timeline, biographies of the many characters and voices in the book, and tons of resources for further study. (Ages 8-15)

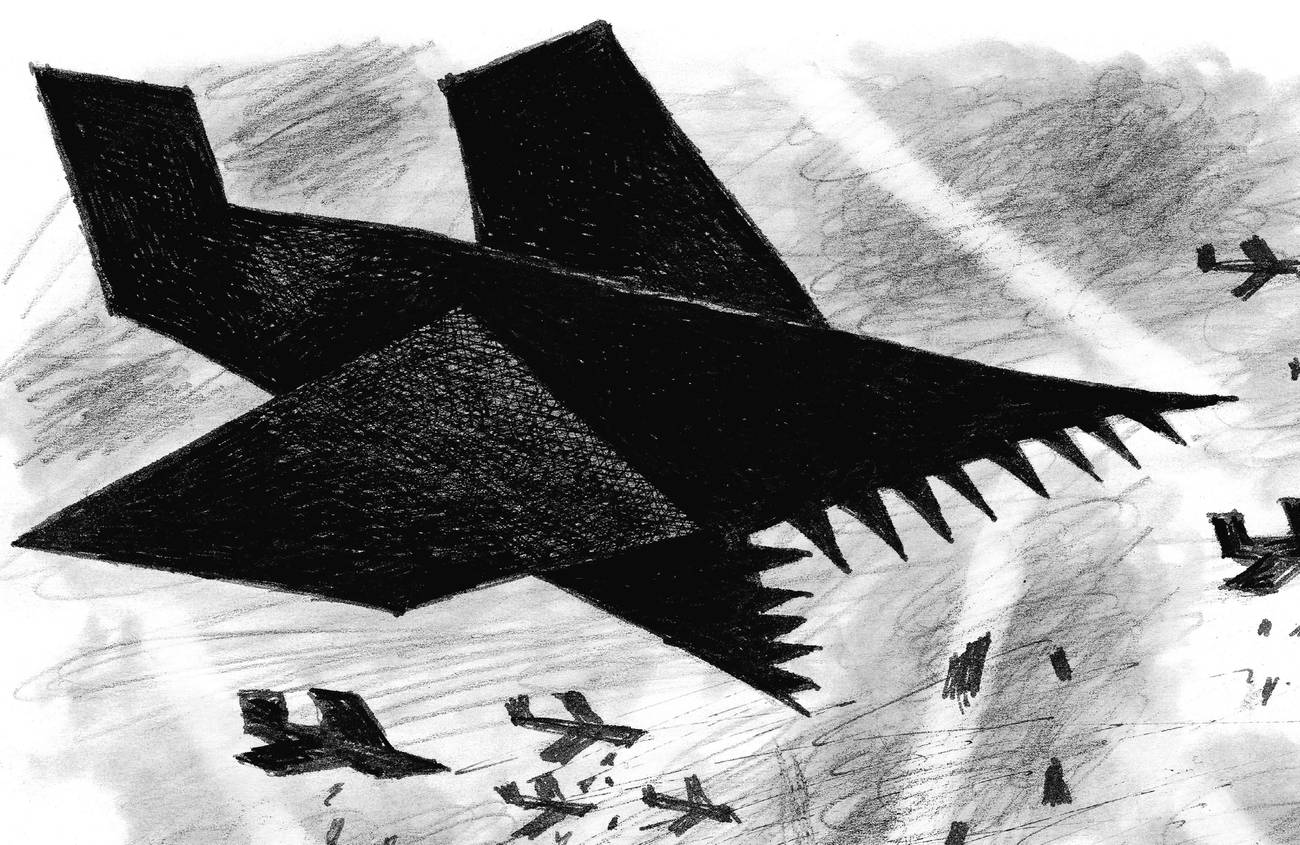

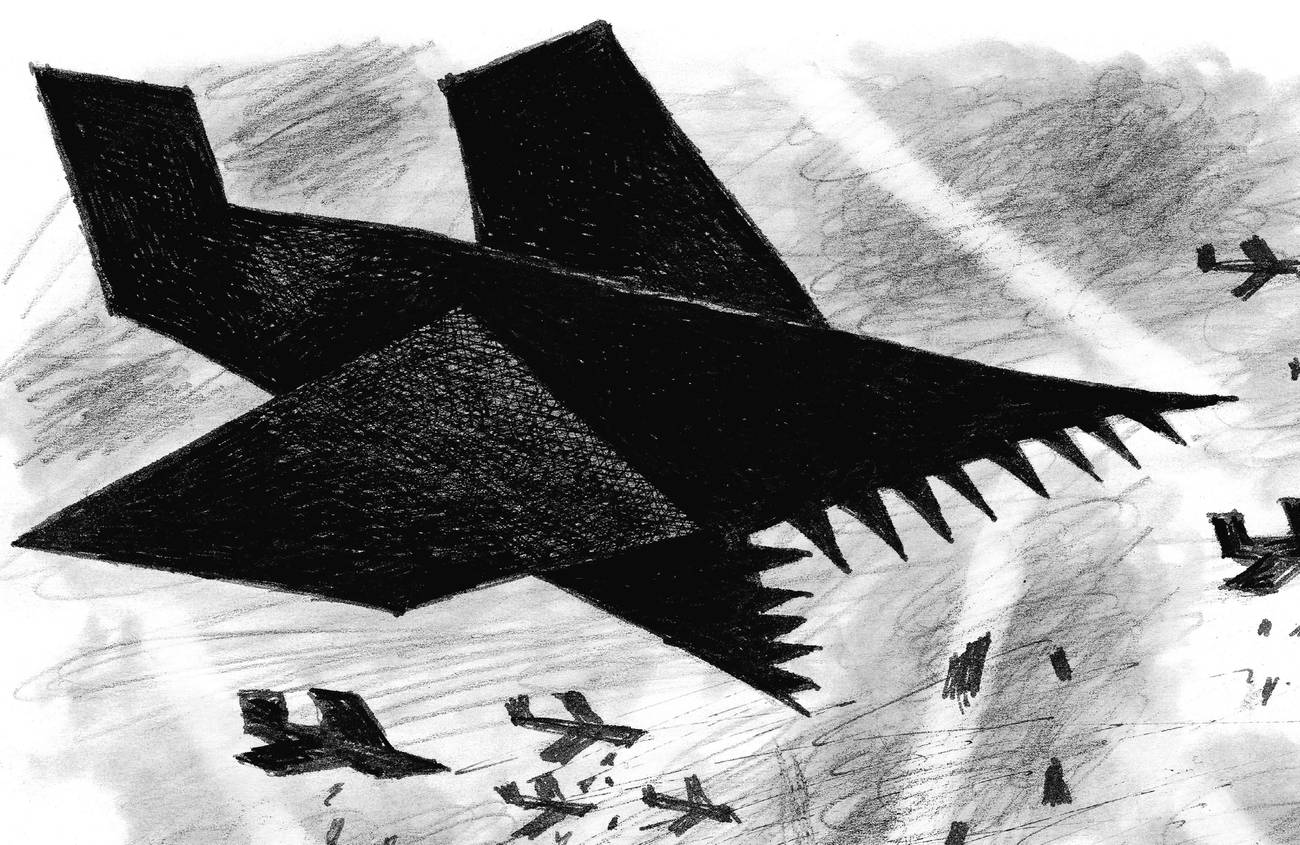

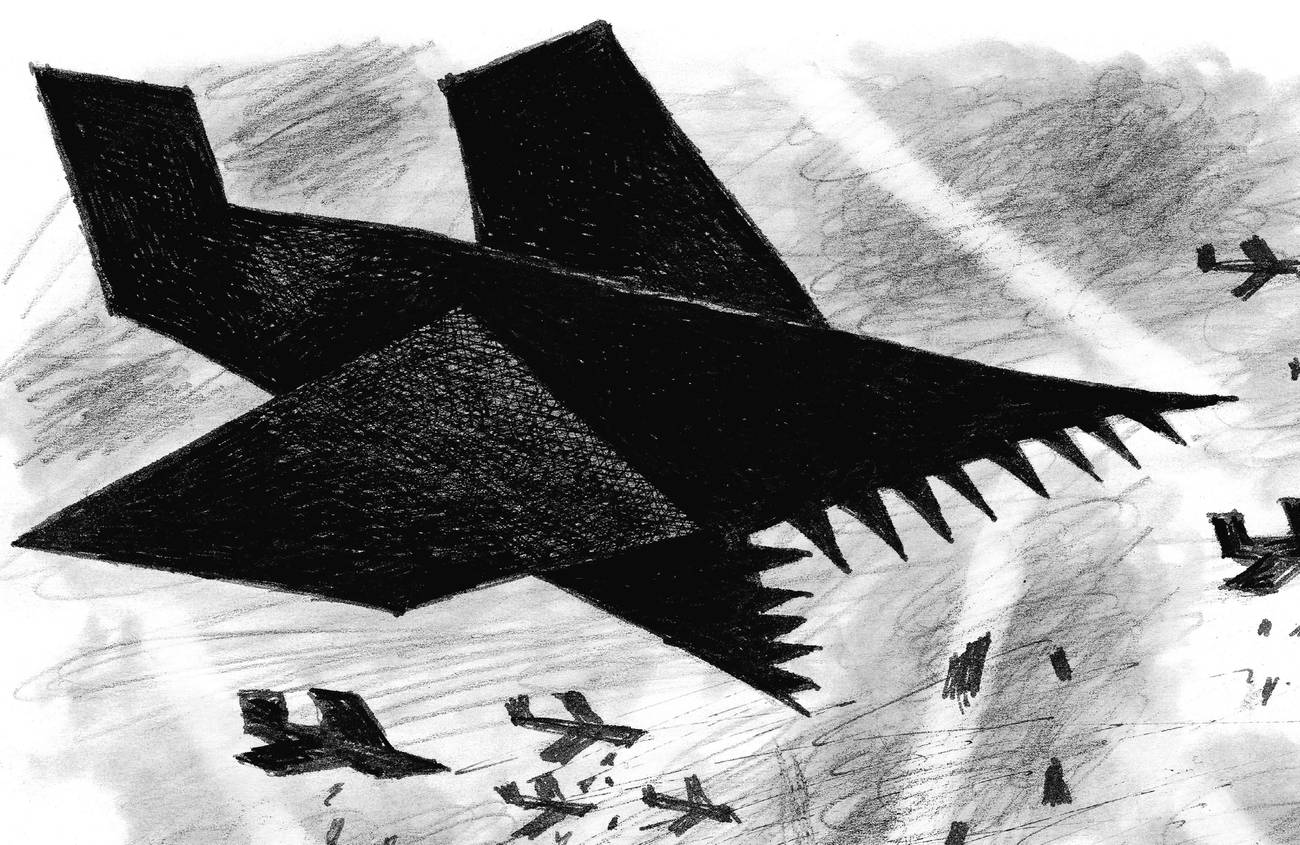

Chance by Uri Shulevitz. Probably shouldn’t be anyone’s first Holocaust book, but a worthy addition to the canon. Caldecott medalist Shulevitz, now 85, is a big macher in children’s literature, with over 40 books under his belt. The gorgeous publishing treatment this book received befits his stature. It’s huge, with a ton of white space to spotlight Shulevitz’s black-and-white illustrations. The book spans Shulevitz’s eight years as a childhood refugee, tracking his family’s desperate journey through Poland, Russia, Turkestan, and finally the Bavarian Alps. They were frequently starving; Shulevitz’s descriptions of hunger are among the most visceral and harrowing I’ve read in a children’s book. But there’s humor here, too, and the story is suffused with young Uri’s love of creating art. Chance is illustrated with gentle drawings in graphite or charcoal, and sharper-lined ones that seem to be pen and ink, as well as comics, maps, family photos and snippets of Yiddish publications. Shulevitz is relentlessly truthful—one of his great strengths over his entire career as a writer and artist—but that means there’s no false hope in this book. He ascribes his survival to chance. (Ages 10-15)

They Went Left by Monica Hesse. Set in a DP camp after the war, it’s a good choice for strong readers who like mysteries and historical fiction. The book begins after the liberation of Auschwitz, with 18-year-old Zofia desperate to get out of the hospital to go find her little brother Abek, from whom she was separated years earlier. She sets off while still broken in both body and mind to track him down, certain he’s survived, too. We don’t get many post-Holocaust stories set in DP camps; Hesse vividly depicts the layers and layers of flyers with missing people’s faces on them tacked up on walls; the hollow-eyed people with nowhere to go, looking for relatives; the exhausted and overwhelmed volunteers staffing phones and reading Nazi ledgers. Zofia is an unreliable narrator, desperately grasping at half-remembered images and possibilities. She’s not always sympathetic. She meets other teenage survivors, some as haunted as she is, but others determined to find some kind of normalcy and even joy. Crowded together in the barracks and dining hall, they still dance and romance and think about pretty clothes, dreaming of a new life.

We owe it to survivors, as well as to all those who were lost, to tell their stories. We owe it to them to work to make the kind of world in which genocide—not just our own, but that of others—can never happen again. That means not only educating our children, but also fighting bias and hatred in our world right now.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.