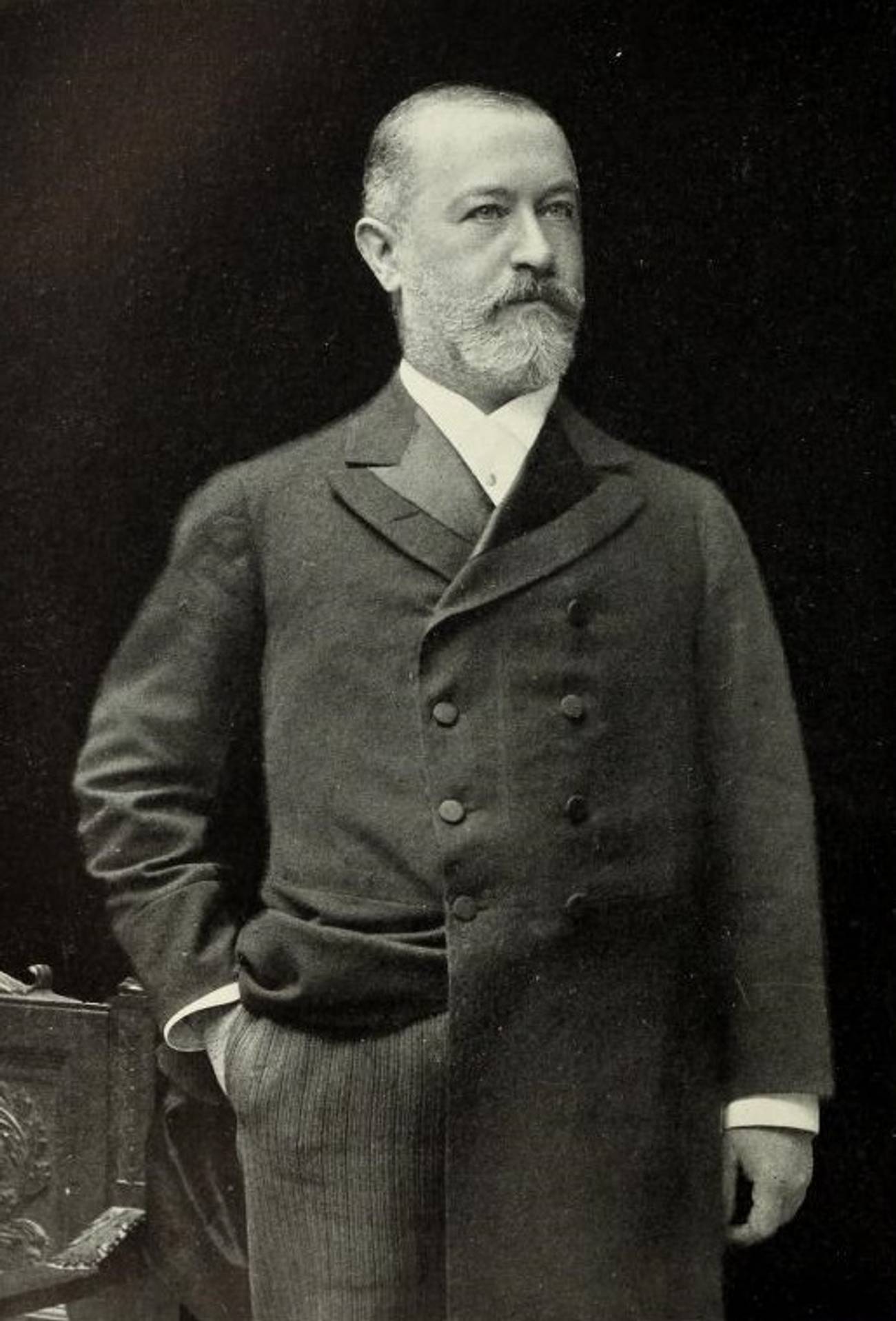

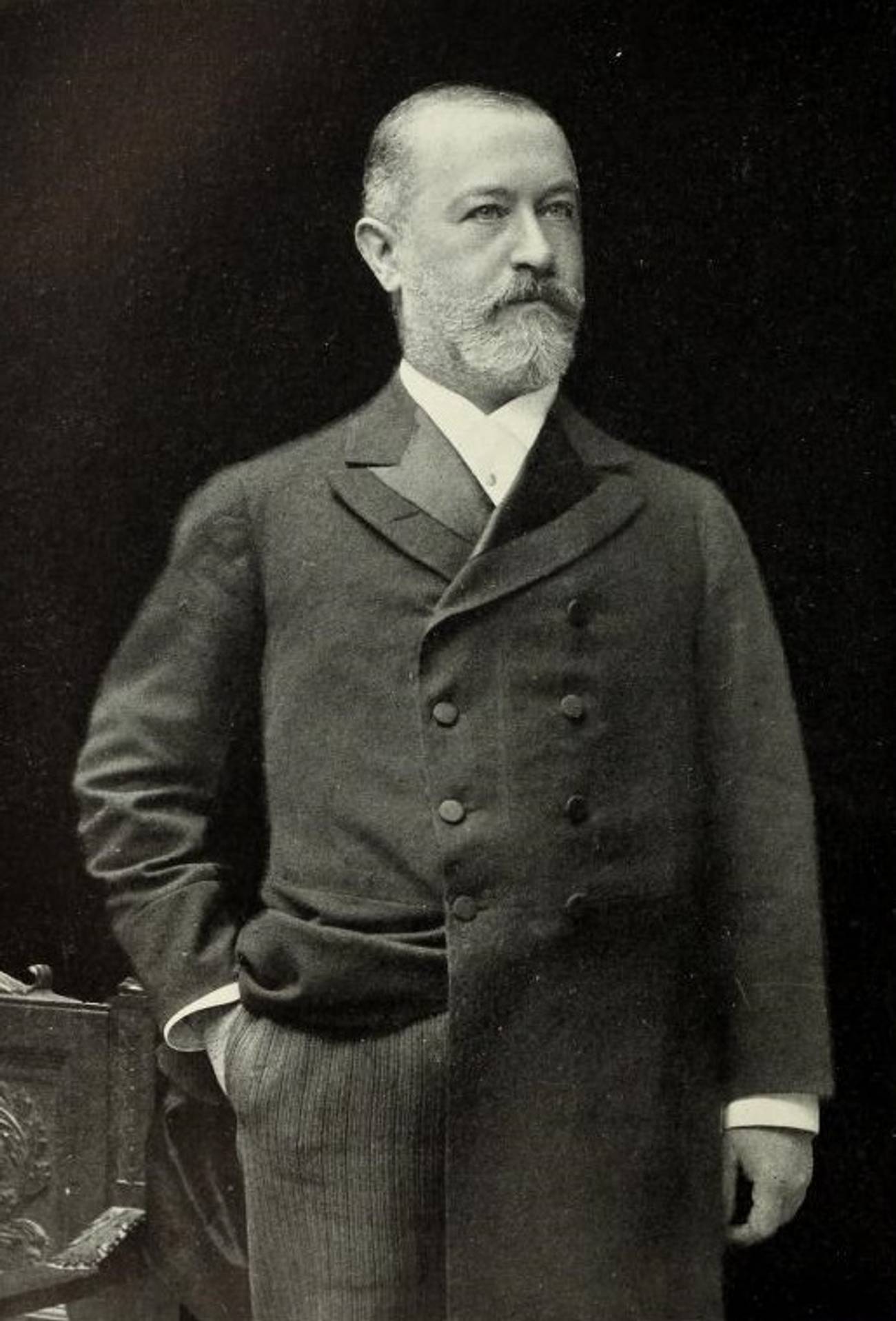

The Engineer of Philanthropy

Jacob Schiff helped shape the American Jewish landscape, and used his influence to promote the notion of Jews becoming unhyphenated Americans

These days, philanthropists are more apt to be pilloried then praised, their actions scrutinized for telltale hints of ill-gotten gains rather than instances of goodwill. Earlier generations of philanthropists, especially those who moved within the orbit of the American Jewish community of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, had it much easier. Glory rather than “gotcha” covered their tracks.

Jacob Henry Schiff was arguably the most celebrated and certainly the best known of the lot. Upon learning of his demise in 1920, at the age of 73, people wept in the streets; stores on the Lower East Side, “plunged in gloom,” brandished mourning banners and closed their doors on the Tuesday morning of his funeral, while thousands thronged the streets outside of New York’s Temple Emanu-El, where it was held.

Another 2,000 in the pews—those fortunate enough to secure an “admission card”—sat reverently throughout the tightly scripted service, touched by its dignity and restraint. “No one present at that Temple funeral will ever forget it,” recalled one of their number.

The press made sure of it. Front-page news as well as the stuff of editorials, Schiff’s passing was amply covered by newspapers as varied as The New York Times and the Jewish Daily Forward. The paper of record highlighted the “magnitude of his achievements” in both the financial and philanthropic sectors of the modern world, before concluding that “Mr. Schiff will be remembered as a great banker, but we think most of all he will be remembered and loved as a great and wise philanthropist.”

The Yiddish paper, in turn, ran true to form. A tad grudging in its assessment, the left-wing daily insisted that it wasn’t the deceased’s philanthropy, the “size of his checks,” that was worthy of praise—after all, it duly noted, “philanthropy is nothing more than a way to refund pennies on the dollar”—but his personality: that of a true “idealist” who took great pride in his Jewish identity.

Schiff’s financial acumen, his perspicacity, fueled his enormous success at the helm of Kuhn, Loeb, an internationally renowned investment banking firm. A believer in the importance of connecting the East Coast with the West Coast, the Atlantic with the Pacific, Schiff financed most of America’s railroads as well as the American Telephone & Telegraph Co., and United States Rubber Co., which placed him within the company of and in league with plutocrats such as J.P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie. The financier’s reach extended overseas as well, enabling him to float a series of loans to Japan when, early in the 20th century, it was at war with Russia, and to enjoy audiences, and on occasion even sup, with kings, emperors, and their consorts, a who’s who of notabilities.

From where Schiff sat, there was only one path forward for America’s Jews: that of being unhyphenated Americans.

For all his hobnobbing, Schiff never lost sight of, or cut himself off, from the common man, in whose well-being he took a personal interest. Clad in his customary attire—a frock coat and top hat, a flower affixed to his lapel—he made it a point every Sunday morning to visit with the residents of the Montefiore Home and Hospital in the Bronx; to greet the many supplicants who found their way to his home or office; to attend and participate actively in an unending series of meetings; and to respond to the thousands of letters that claimed his attention.

Thanks to his fiscal success and his deep-seated concerns for the welfare of his coreligionists, this “engineer of philanthropy,” as one of his admirers put it, went on to shape the modern American Jewish landscape, which would have looked entirely different—less comprehensive, custodial, and stable—had it not been for his benefactions. Name a contemporary Jewish organization—the American Jewish Committee, say, or the Hebrew Free Loan Society, the Jewish Theological Seminary, or the Jewish Publication Society—and chances are that Schiff had a hand in its formation and maintenance.

Secular institutions, especially those that disseminated knowledge, among them Harvard’s Semitic Museum, the Library of Congress, and the New York Public Library, were also the recipients of his largesse, as was the Tuskegee Institute, the Red Cross, and the Henry Street Settlement, whose efforts at bettering the welfare of the poor had a “stronghold on his heart and mind.”

Despite the many claims on his time and resources, Schiff lived a full life, balancing the responsibilities of philanthropy with the press of business and reconciling both enterprises with his personal affinity for walking, which he did daily, and bicycling, which he took to when spending time at his country home. Though said to prefer “old things,” especially carriages to automobiles—“his horses slowly made way for the swifter motor,” a bemused colleague recalled—Schiff had an adventurous spirit, prompting him to ascend in a zeppelin on one occasion and to travel to Europe on 20 others. He also crossed the American continent five times, and visited Palestine, Egypt, Algeria, and Japan, where he and his wife, Theresa, spent eight weeks in 1907.

While in motion in the Far East, Schiff wrote vivid, detailed, and often amusing letters back home, which his wife subsequently compiled into a book and presented to her husband as a “surprise” on his 60th birthday. Printed on “Japan paper,” its title page rendered in faux Japanese letters, a copy of Our Journey to Japan now resides at the American Jewish Archives, along with a hefty complement of Schiff’s papers.

In his travelogue, Schiff brings to life the people he and his wife encountered along the way, including the mikado, who, in appreciation of the financier’s support, bestowed on him the Order of the Rising Sun; the food they consumed, distinguishing between “occidental” cuisine, which Schiff and the members of his party favored, and “foreign style” fare, which they did not; the sites they took in, the “curios” they purchased, and the fine points of etiquette. In one instance, while seated on the floor atop low cushions during a ceremonial luncheon that went on and on, Schiff told of leaping to the opportunity (and his feet) to propose a toast to his hosts, “ostensibly to reply, but in reality, to stretch a bit.”

How was the man able to do and absorb so much? Perhaps the key resided in the to-do lists he compiled on a “little tablet,” which, his family recalled, he “methodologically went through until the slate was wiped clean.”

Though not on the Sabbath.

Schiff had grown up in an Orthodox Jewish home in Frankfurt, Germany, but once in the New World, became a member of New York’s two leading Reform synagogues, Temple Emanu-El and Temple Beth-El. “No Jew,” he liked to say, perhaps thinking of himself, “could be a good Reform Jew unless he had once been an Orthodox Jew.” Synthesizing the ideology of the first with many of the ritual practices of the second, Schiff reserved Friday evenings for his family and refrained from working on Saturday, spending his mornings instead at Temple Beth-El, to which he walked from his “palatial” home at the corner of 78th Street and Fifth Avenue.

During the rest of the week, Schiff was said to have recited his morning prayers as well as grace after meals and to have kept kosher. For the most part. His grandson, Edward M.M. Warburg, noting that Schiff had his own “ground rules,” related that there were some “glaring exceptions” to his grandfather’s dietary practices: “lobster and bacon somehow sneaked in under the wire!”

A model citizen and a good Jew, Schiff was not without his flaws, of which the most publicly remarked upon was his short fuse. Even Cyrus Adler, Schiff’s longtime friend and future biographer, acknowledged his subject’s “quickness of temper [and] momentary insistence upon his own judgment,” in an otherwise laudatory “sketch” he published shortly after his death.

Over the years, Schiff locked horns with many Jewish luminaries, from Israel Zangwill, who recalled having “been more than once in collision with [Schiff’s] conceptions or pre-conceptions,” to Solomon Schechter, president of the Jewish Theological Seminary. “These two strong natures … occasionally clashed,” Adler related, referring to Schiff and Schechter, “but they were both big men, and their differences ended in a laugh, Mr. Schiff saying ‘we are both Cohanim (priests) and priests traditionally have high tempers.’” The philanthropist-cum-priest, his biographer was quick to add, never held a grudge for long and would, after some contemplation, often come round to another’s point of view, conceding that, yes, he could be “hasty.”

Sometimes, though, America’s “foremost Jew” stuck to his guns. In 1916, after reading in The New York Times of an inflammatory commencement address given at the Jewish Theological Seminary by Mordecai Kaplan, then coming into his own as one of American Jewry’s leading lights, Schiff took considerable offense. What made him see red was Kaplan’s denunciation of the perspective that held that “it is more important to be a good American than to be a good Jew, or that we should be Americans in public, Jews in private,” a posture he witheringly dismissed as “tawdry music-hall patriotism.” Although Kaplan claimed that his intention was not to single out the philanthropist, who was known publicly to have endorsed this position, the latter refused to be mollified.

It wasn’t just that Kaplan’s remarks rubbed Schiff the wrong way, wounding his amour propre. No ordinary tiff, the tension between the two pivoted on, and went to the very heart of, competing notions of how the American Jewish community envisioned itself. From where Schiff sat, there was only one path forward for America’s Jews: that of being unhyphenated Americans. Anything that diverged from that notion, that placed as much or perhaps even more of an emphasis on Jewish national identity, on the distinctiveness of one’s coreligionists, diminished the pedigree of being, or becoming, an American, and was not to be countenanced.

By his own admission “not a race-Jew, but a faith-Jew,” Schiff gave voice time and again to his unqualified love of the United States. When, at long last, he was back on American soil after his trip to Japan, he wrote lyrically of the New World and of its inhabitants, the “millions who are driven from the narrowness of the Old World, [who] are turning the North American wilderness into God’s paradise, a happy haven.”

He counted himself among them, prompting Louis Marshall, yet another longtime colleague and friend, to remark that Schiff was “as much an American as if he had come over on the Mayflower.”

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.