Tomatoes at their ripest, peaches at their juiciest, lazy days spent doing not much of anything: summer at its peak. For those of us in the business of education, though, the calendar reads “fall,” as we ready ourselves and our curricula for the school year. Jewish educators are especially busy just about now since their portfolio also includes figuring out how to make the most of the cluster of Jewish holidays that comes quickly on the heels of the first weeks of the new term.

These days, Jewish education appears to be a thriving concern, or at least a stable one. Though not every contemporary American Jewish child receives, or even wants, a Jewish education, there’s no shortage of opportunities. A galaxy of graduate programs, foundations, think tanks, institutes, and communal professionals sees to it that the transmission of Jewish knowledge is alive and well in 21st-century America and that those who do the transmitting are well-trained and held in high regard.

A century earlier, there was no shortage of opportunities, either, though they weren’t exactly esteemed. Sunday schools and bar mitzvah “factories,” the cheder and the yeshiva, the communal Talmud Torah, the congregational Hebrew school, the Yiddish schule, and, here and there, a Jewish parochial or day school crowded the landscape, each with a distinctive sensibility, constituency, and purpose. Two things bound them together: first, their inability to recruit and retain students, for whom Jewish education was no one’s idea of fun—a “theft of time” was more like it; and second, their inability to recruit and retain teachers, for whom Jewish education was no one’s idea of gainful employment.

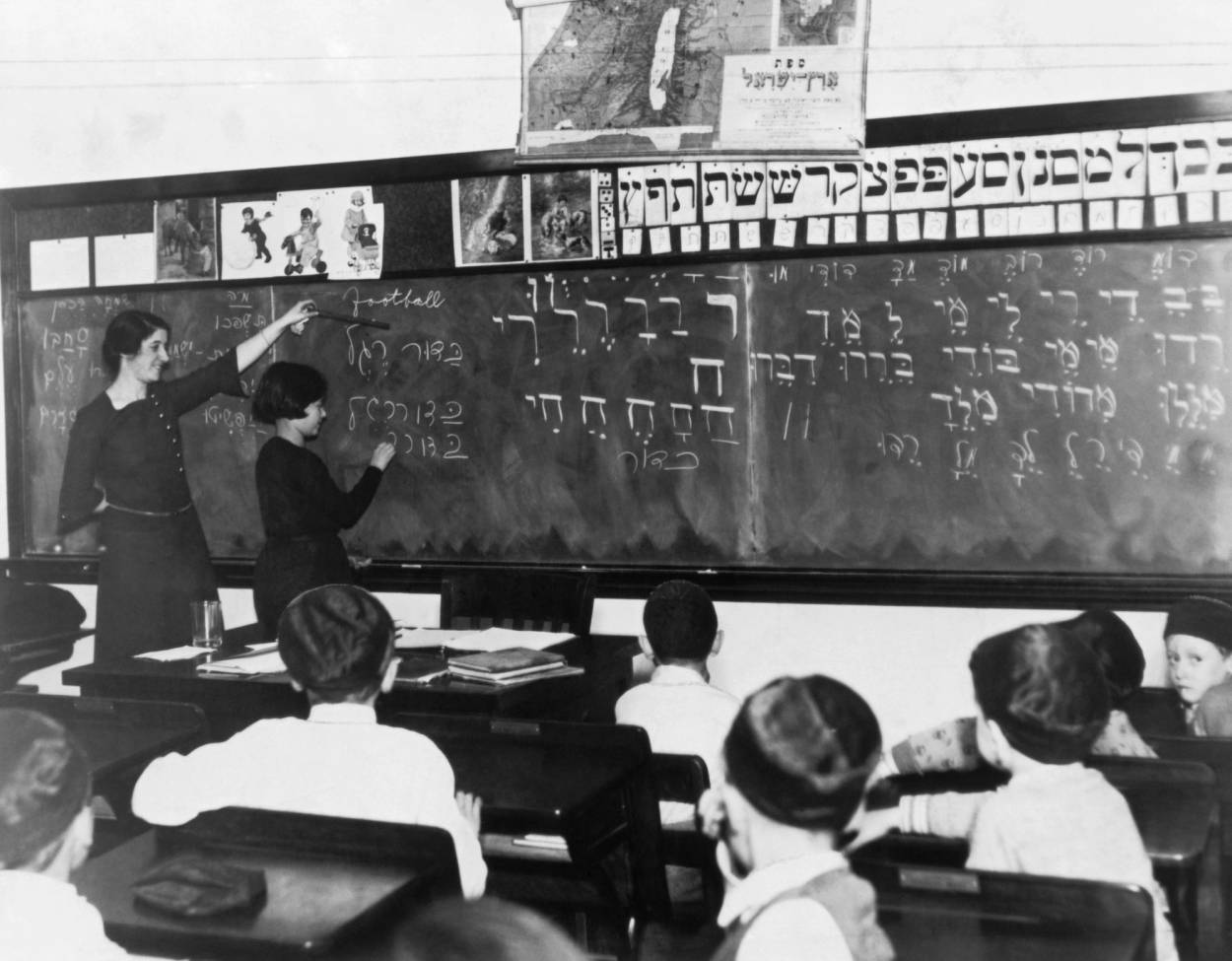

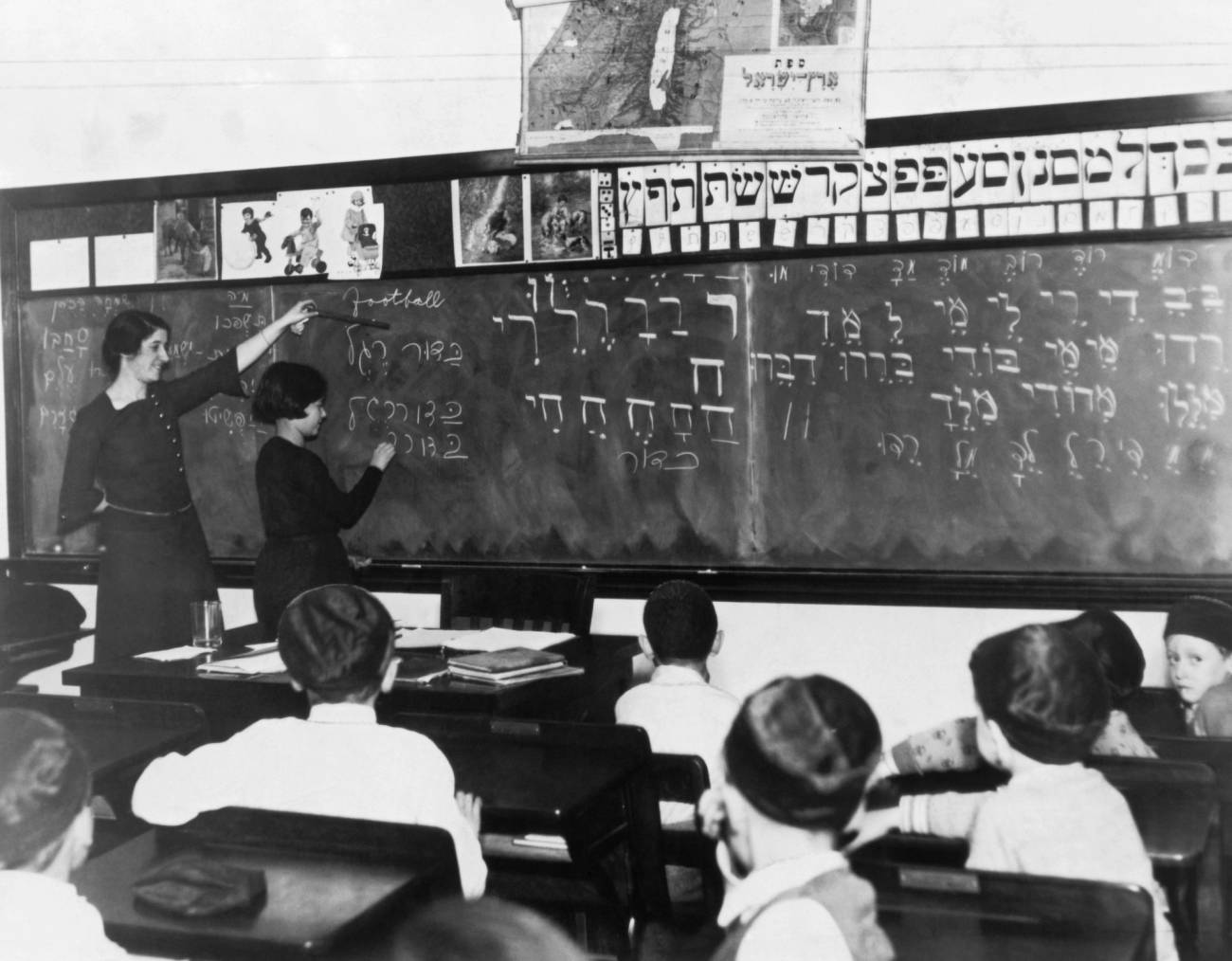

In the hope of keeping everyone in their seats and happy, Jewish educational authorities of the 1910s and ’20s looked to modernization. Opening up the Jewish classroom to girls as well as boys, while drawing on the most up-to-date pedagogical theories and the latest bells and whistles, they sought to render it an attractive site—literally.

A wholesome environment was key to whatever success Jewish educators might enjoy. It didn’t take much to realize that a brightly lit, well-ordered, and colorfully decorated room would attract, where a dark, dank, and dreary one would deter. And yet, for far too long, the Jewish classroom remained an inhospitable space. Improvised rather than intentional, it “chills enthusiasm and is detrimental to the welfare of both teachers and pupils,” observed Alexander Dushkin, a leading proponent of modern Jewish education, in 1918. His teacher, Samson Benderly, who, arguably, did more than anyone in the United States to elevate the status of Jewish education in the prewar era, put it more starkly: “What can our children think of Judaism if after their stay in the modern public school buildings, we offer them Jewish classrooms which are badly ventilated and poor lighted and which are very often not kept clean?” His answer: not very much. Jewish children were “bound to interpret the entire heritage of our people in the terms of the physical side of the classroom.”

Negative associations like these were not the exclusive purview of the young. New York City’s Department of Health felt the same way. Acting in 1915 on an anonymous tip about the lamentable physical conditions that obtained in many of the city’s Jewish educational institutions, it investigated the matter and discovered that germs were just about everywhere, especially in what passed for the bathroom. The absence of cleanliness and proper hygiene in these facilities was so striking, the inspectors reported, that they “would not bear very favorable comparison with the Southern school privy, against which sanitarians hold up their hands in horror.”

Something had to be done, and fast, to redeem the community’s good name. To the rescue: the school as laboratory. When the Central Jewish Institute, an up-to-the-minute facility on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, opened its doors in 1916, its founders made a point of installing classrooms that were every bit as clean, ordered, and scientifically oriented as the site of experiments. Proud of their efforts, they—and comparable institutions that soon followed—took and circulated photographs that depicted bright and airy spaces filled with neat rows of bright-eyed and neatly attired students, their eyes fastened on an array of visual aids that included a large-sized blackboard, charts, and maps.

The curriculum, as well as its context, was also in need of a systematic overhaul. Memorization and rote learning were the order of the day in most Jewish educational institutions; opportunities for engagement far and few between, and the bill of fare narrow and outdated. Is it any wonder, then, that most students emerged from their mercifully brief encounter with Jewish education bored to tears, if not downright disdainful, capable of little more than mumbling their way through the siddur?

If modern Jewish educators had their way, textbooks and manuals would be consigned to the dustheap of discarded pedagogy. The lively arts would take their place, stimulating the Jewish child’s interest, not dampening it, and rendering education as much a tactile and visual experience as a textual one. Song, dance, dramatics, and storytelling became the vehicles of instruction, along with the Ivrit b’Ivrit method of teaching Hebrew the “natural” way through immersion and play. Transforming a dead letter of a language into a living, breathing, contemporary form of expression, this approach extended Hebrew’s range of motion from prayer to conversation (that was the plan, at least).

Zionism animated the entire enterprise, furnishing it with a sense of novelty and adventure, especially when allied with the most modern forms of technology, from the use of stereopticon or magic lantern slides to plaster casts and Hebrew typewriters. Though they featured more than their fair share of camels, stereopticon images of modern-day Palestine, of brawny men and women in shorts (shorts!) tilling the soil, probably did more for the imagination than the most avid reading of the Bible. Plaster casts of recent archaeological discoveries also brought the past to life, placing ancient Jewish history within reach, while Hebrew typewriters made possible the speedy production of classroom materials.

Zionist-infused schools were not the only game in town. A parallel universe of facilities where Yiddish rather than Hebrew was the linguistic coin of the realm and a decidedly secular and diasporic-centered curriculum enthusiastically promoted also drew thousands of Jewish children. Like its Zionist counterpart, but with a focus on Vilna, the “Jerusalem of Lithuania,” rather than the City of David, the Sholem Aleichem folksschule, for example, also drew on the latest forms of pedagogy and technology to transmit the lingua franca and cultural heritage of Ashkenazi Jewry to a new generation.

In both iterations, whether in Hebrew school or in schule, for two hours a week or seven, these interventions, or educational “reforms,” were designed to make the time pass quickly, enjoyably, and meaningfully.

Not surprisingly, they met with a shower of objections from just about every quarter. Parents whose view of Jewish education was entirely instrumental, who believed that what mattered was the how, not the why, of reading Hebrew, frowned on the Ivrit b’Ivrit approach, complaining that its salutary results were too long in coming. The Orthodox community’s gatekeepers, when not issuing broadsides against the advocates of yidishkayt, whose cultural perspective they decried, were just as likely to point out the limitations of the modern approach to religious education. The latter, they charged, “made a ‘show’ of the Torah and our holy prophets. They changed these spiritual giants into moving picture heroes.” Meanwhile, the members of the philanthropic community, most of whom had no truck with and little use for either Yiddish or Hebrew, couldn’t understand why their resources were being deployed for foreign language acquisition when the chances of young American Jews speaking another tongue were slender at best. And, of course, the traditional Hebrew school teacher, the melamed, grumbled the loudest of all. Increasingly displaced, a fish out of water, no one had more to lose than he, whose old-fashioned methods of instruction and fits of temper, born of frustration, did little to endear him to his rambunctious young charges.

Overcoming these varied objections was not easy, but modern Jewish teachers, many of them women like my beloved mother-in-law, Judith Hochstein Joselit, stuck to their guns. The products of newly established teacher training institutes throughout the country—New York’s Teachers Institute, Baltimore Hebrew College, Boston Hebrew College, and Chicago’s College of Jewish Studies among them—they saw Jewish education as a profession, not just a job. “Armed to the teeth with technique,” as one of their number would have it, and imbued with a strong esprit de corps, they knew their way around a classroom, zealously guarding its precincts and their prerogatives.

In due course, they, too, found themselves on the receiving end of criticism and, to make matters worse, from one of their own: Midge Decter, a graduate of the Teachers Institute and a frequent contributor to Commentary. With her characteristic blend of verve and snippiness, she laced into the Jewish educational scene, circa 1951, poking fun at the transformation of the classroom into a playroom whose students came away knowing the Hebrew names of vegetables, but hardly anything of the Bible, and whose teachers believed the “function of Jewish education was to make children ‘adjusted’ as Jews,” rather than disseminate knowledge. Modernization, Decter insinuated, had gone too far.

But then, so had she. Jewish education was, and continues to be, a balancing act perched between intellect and affect, content and delivery, tradition and change, past and present. It’s anyone’s guess as to what really works—or sticks.